| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 4, Number 10, October 2013, pages 662-666

Massive Pulmonary Embolism With ST Elevation in Leads V1-V3 and Successful Aspiration Thrombectomy: Case Report and Review of EKG Changes in Acute Pulmonary Embolism

Khalid Mohammada, d, Humberto Sasieta-Tellob, Sridhar Badireddic

aDepartment of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and VA Hospital, 13500 Chenal Parkway, Apt # 2731, Little Rock, AR 72211, USA

bDepartment of Internal Medicine, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and VA Hospital, 4301 W Markham Street, Slot # 555, Little Rock, AR 72205,USA

cDepartment of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and VA Hospital, 4301 W Markham Street, Slot # 555, Little Rock, AR 72205, USA

dCorresponding author: Khalid Mohammad, Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and VA Hospital, 13500 Chenal Parkway, Apt # 2731, Little Rock, AR 72211, USA

Manuscript accepted for publication August 5, 2013

Short title: STEMI in PE

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/jmc1423w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Pulmonary embolism (PE) lacks an acute specific electrocardiographic pattern. It can infrequently masquerade as ST-elevation myocardial infarction (MI). We report a case of massive pulmonary embolism, presenting as an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and anteroseptal ST-elevation. The diagnosis was made by pulmonary angiography. Aspiration thrombectomy was performed immediately following the diagnosis, with a good outcome.

Keywords: Pulmonary embolism; ST-elevation myocardial infarction; Aspiration thrombectomy

| Introduction | ▴Top |

PE is a frequent cause of sudden death, associated with several risk factors including pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, immobility, cancer and pro-coagulant disorders [1]. The presentation of acute PE is protean, ranging from subclinical to acute heart failure. Cases of severe right heart strain/failure have presented with ST segment elevation. A high index of suspicion is needed to identify these occurrences, as their frequency is very low. A recent retrospective study of 800 ST-elevation cases in an academic medical center, revealed 2.3% of non-cardiac causes for ST-elevation, but found no cases of PE [2].

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 63-year-old Caucasian man with a past medical history of esophageal cancer was brought to the emergency department with symptoms of acute onset chest pain, diaphoresis and shortness of breath that started 30 minutes ago. He suffered a cardiac arrest (pulseless electrical activity) en route. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was instituted by emergency medical services with return of spontaneous circulation within 15 minutes. On admission he was afebrile, with a pulse of 110/min, blood pressure 60 mmHg systolic, respiratory rate 20/min and oxygen saturation 100% while on FiO2 100%. Chest and cardiac auscultation were unremarkable. The extremities were cold, clammy and mottled.

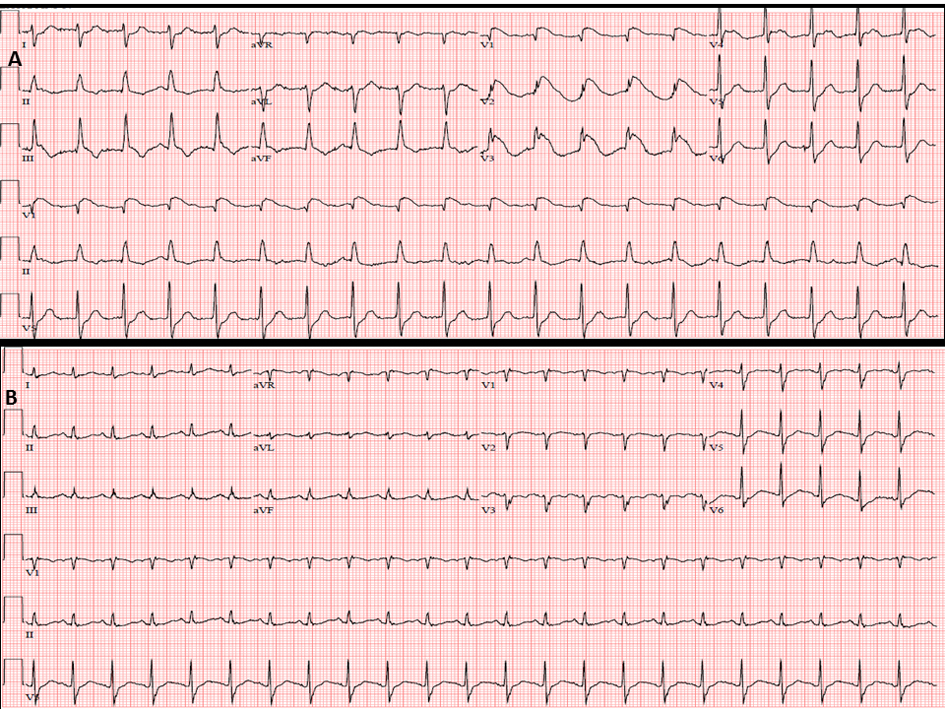

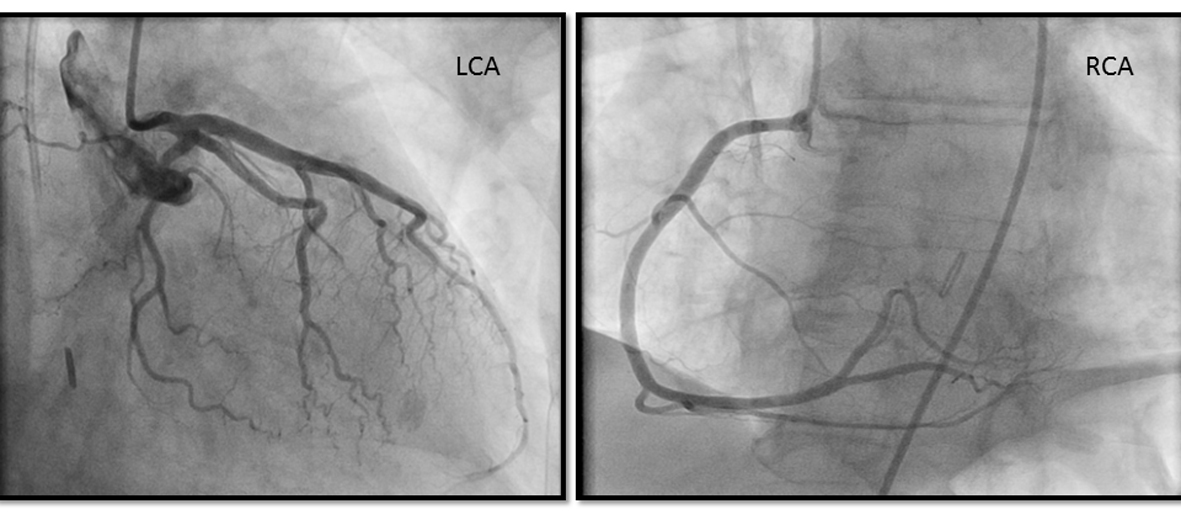

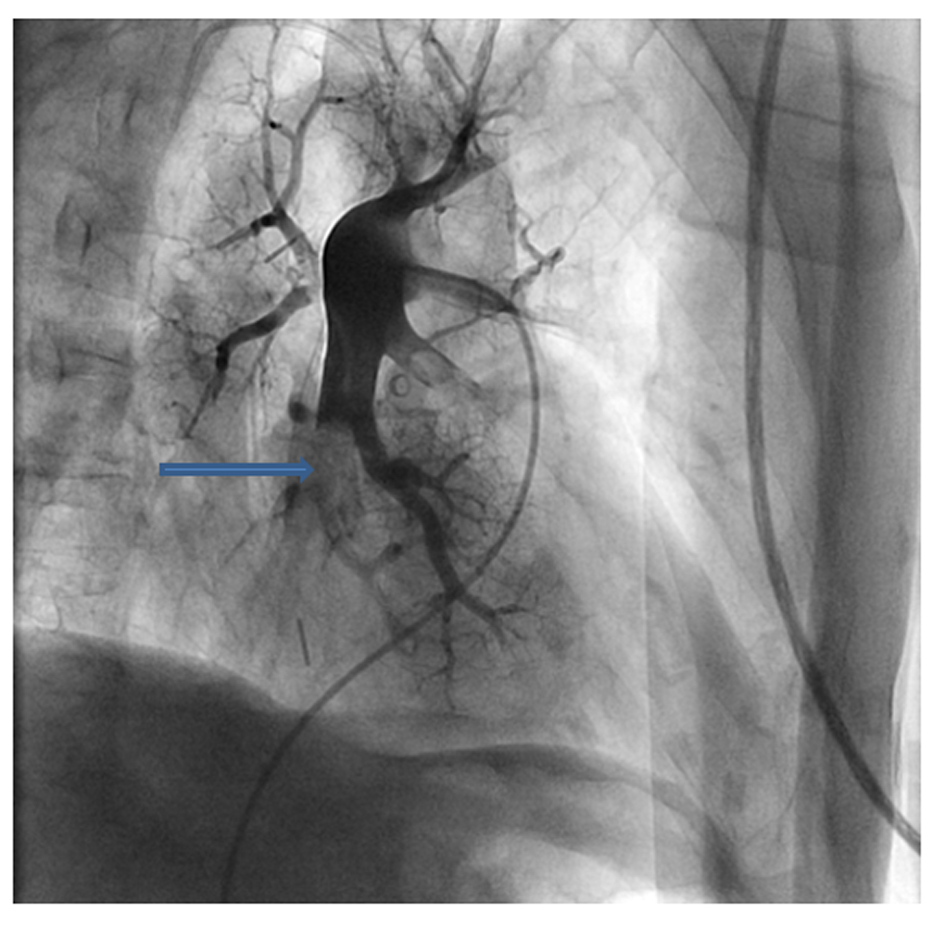

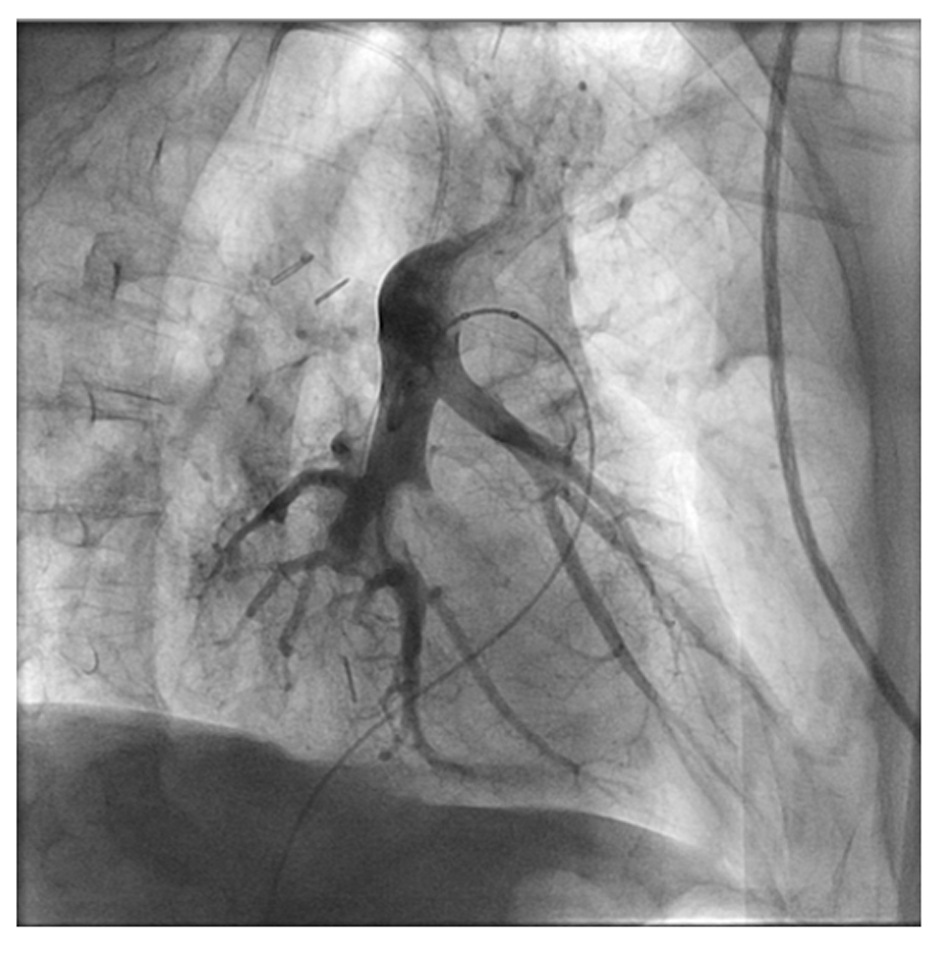

Initial laboratory studies showed leukocytosis, metabolic acidosis with a serum lactate of 5.5 mMol/L and a serum troponin I of 1.07 ng/mL. Chest X ray was unremarkable. A 12 lead EKG (Fig. 1A) showed ST elevation in leads V1-V3 with reciprocal ST depression in V5-V6. The cardiac catheterization laboratory was immediately activated and coronary angiogram done showing normal coronary anatomy (Fig. 2). Due to the persistent hypotension a pulmonary angiogram was performed to look for a pulmonary embolus. A large embolus was seen obstructing the main pulmonary artery (Fig. 3). Intra-arterial tissue plasminogen activator was given and aspiration thrombectomy performed (Fig. 4). There was remarkable improvement in the hemodynamics with resolution of the hypotension and decrease in the pulmonary artery systolic pressure from 42 mmHg to 32 mmHg. A 12 lead EKG done after the procedure showed resolution of the ST elevation (Fig. 1B). The patient was extubated the next day and transferred to the general medical ward on anticoagulation with low molecular weight heparin.

Click for large image | Figure 1. The 12-lead EKG showing ST elevation in V1-V3 with reciprocal ST depression in V5-V6 (A). Resolution of ST elevation in EKG done after aspiration thrombectomy (B). |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Coronary angiogram showing patent left and right coronary artery. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Pulmonary angiogram showing a large embolus obstructing the main pulmonary artery (arrow). |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Pulmonary angiogram after aspiration thrombectomy showing patent main pulmonary artery. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Despite new technologic advances, the diagnosis of acute PE remains challenging. Approximately 10 to 30% of cases of acute massive PE are not diagnosed until discovered on autopsy [3, 4]. A number of specific EKG findings have been described in association with acute PE. Some investigators have attempted to develop diagnostic prediction rules based on EKG findings [5]. As these findings are quite variable, such efforts have met with limited success. Recent work has focused on the ability of the EKG to reflect the severity, duration, and prognosis for patients with acute PE.

EKG findings

Ever since McGinn and White first reported in 1935 the classic “S1Q3T3” pattern finding (described as a prominent S wave in lead I, ST segment ascent in lead II, and Q wave with inverted T wave in lead III) in seven patients with acute cor pulmonale secondary to PE, several studies have described a wide range of specific EKG abnormalities associated with PE [6]. The large majority of these studies are specific to patients with no preexisting cardiac or pulmonary disease.

Normal EKG

A completely normal EKG has been reported in 9 to 26% of patients with acute PE [3, 7]. Sreeram et al reported normal EKG in one quarter of acute PE patients on admission. Majority of these patients (18%) had EKGs that remained normal throughout their hospitalization [5].

Rhythm disturbances

Rhythm disturbances, including sinus tachycardia, first degree atrio-ventricular block, premature atrial and ventricular beats, atrial fibrillation, and flutter have been reported in association with acute PE at varying rates. Atrial fibrillation and flutter were reported to occur in as many as 18% and 35%, respectively, of acute PE patients by Weber et al and Sreeram et al, and as few as 0 to 3% in other studies [5, 8].

Right bundle branch block

Complete or incomplete RBBB has been described as a “typical”, but variable finding with an incidence ranging from 6% to as high as 67%. In addition, RBBB can be associated with ST segment elevation and upright T waves in lead V1, potentially mimicking anteroseptal or posterior infarct patterns [5]. Right bundle branch block in the setting of acute PE is often transient and has been reported to resolve in most cases within 14 to 41 weeks of onset [9, 10].

Axis changes

Right, left, and indeterminate QRS axis changes have been reported with variable frequency in acute PE patients. Whereas RAD is described as the classic axis change associated with PE, some investigators have reported left axis deviation (LAD) as occurring with greater frequency [5, 9, 11]. Part of the variability may relate to the different parameters defining RAD, LAD, and indeterminate deviations. Indeterminate axis have been defined as axis ranging from 180° - 90°, a range that also has been described as extreme or superior RAD. In addition, preexisting disease may impact the incidence of axis deviations. In the Urokinase in Pulmonary Embolism Trial, Stein et al reported that LAD occurs more frequently than RAD in the PE study population; however, when those with preexisting cardiopulmonary disease are excluded, the incidence of LAD and RAD are equivalent [9].

Transition zone shift

Clockwise rotation and shift of the transition zone (the precordial lead site where R and S wave amplitudes are equivalent) to lead V5 has also been reported with variable frequency in PE patients. Sreeram reported an incidence of as many as 51% of PE patients with evidence of transition zone shift to V5 [5].

Morphologic changes

Along with sinus tachycardia, the most common EKG abnormalities associated with acute PE patients are morphologic, particularly alterations in the ST segment and T wave.

P wave

Increase in the P wave amplitude greater than 2.5 mV in lead II (p-pulmonale) has classically been attributed to right atrial hypertrophy or enlargement associated with acute PE [5]. P-pulmonale has been reported in anywhere from 2 to 31% of PE patients [8, 12]. In addition, Petruzzelli and Manganelli reported PR depression and displacement in nearly one-third of PE patients studied [13, 14].

QRS wave

Low voltage (less than 5 mV in all limb leads) in the QRS wave in all limb leads has been reported in up to 29% of PE patients [15]. Other QRS wave findings reported with acute PE include a late R wave in avR and slurred S in V1 or V2 [12].

ST segment and T wave

Alterations in the ST segment and T wave are the most frequent changes seen on EKG in PE patients [5, 7]. Nonspecific ST depression or elevation has been reported in up to half of all PE patients [13, 14]. T wave inversions diffusely and in the inferior or anterior leads also have been frequently reported.

In PE the pattern of ST elevation in anteroseptal wall is extremely rare [16]. None of the published studies listed ST segment elevations in leads V1-V4 as a characteristic finding. There have been a few case reports describing ST-elevation in acute PE. Falterman and colleagues reported a case of PE with ST segment elevation in leads V1-V4 in a patient who died despite resuscitative efforts [17]. Livaditis et al reported a case of massive PE with ST elevation in leads V1-V3 and successful thrombolysis with tenecteplase [18].

S1Q3T3

The finding of a large S wave in lead I, Q wave and inverted T wave in lead III has often been mistaken as pathognomonic for acute PE after being first described in the 1930s [6, 7]. The reported incidence of the S1Q3T3 combination has varied from 10% to as high as 50% of acute PE patients [19]. Sreeram reported separate frequencies for an S wave greater than 1.5 mV in leads I and L (73%), Q wave in III and F (49%), and T wave inversion in III and F (33%) in a study of 80 patients with confirmed PE [5]. Stein reported that, similar to RBBB, S1Q3T3 is frequently transient, resolving within 14 days after onset of the disease [20].

Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy

Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy (PMT) is an alternative approach for reversing massive PE related right ventricular dysfunction and cardiogenic shock, being particularly useful in patients in whom thrombolysis is contraindicated or surgical embolectomy is neither feasible nor available [21]. An expert panel of the American College of Chest Physicians has recommended the use of PMT in selected patients [22]. Koning et al were the first to report improvement in pulmonary artery pressure in one of two patients treated with aspiration thrombectomy [23]. There have been a few other case reports and case series evaluating the safety and efficacy of aspiration thrombectomy in massive PE. However there has been no case report documenting the use of percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy in PE presenting as a ST elevation.

Conclusion

In PE the pattern of ST elevation in anteroseptal wall is extremely rare. Early thrombolysis may be life-saving and if the patient is hemodynamically unstable, reperfusion with aspiration thrombectomy can lead to a rapid recovery. In conclusion, PMT is an attractive therapeutic alternative in patients with and requires further evaluation to adequately define its role in the treatment of massive PE.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

Abbreviations

CPR: Cardiopulmonary resuscitation; EKG: Electrocardiogram; LAD: Left anterior descending; MI: Myocardial infarction; PE: Pulmonary embolism; PMT: Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy; RAD: Right anterior descending; RBBB: Right bundle branch block

| References | ▴Top |

- Senior RM. Pulmonary embolism. In: Bennett JC, Plum F, Gill GN, Kokko JP, Mandell GL, Ockner RK, eds. Cecil textbook of medicine. 20th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1996:422-429.

- dos Santos ES, Minuzzo L, Pereira MP, Castillo MT, Palacio MA, Ramos RF, Timerman A, et al. Acute coronary syndrome registry at a cardiology emergency center. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2006;87(5):597-602.

pubmed - Panos RJ, Barish RA, Whye DW, Jr., Groleau G. The electrocardiographic manifestations of pulmonary embolism. J Emerg Med. 1988;6(4):301-307.

doi - Palla A, Petruzzelli S, Donnamaria V, Giuntini C. The role of suspicion in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Chest. 1995;107(1 Suppl):21S-24S.

doi pubmed - Sreeram N, Cheriex EC, Smeets JL, Gorgels AP, Wellens HJ. Value of the 12-lead electrocardiogram at hospital admission in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 1994;73(4):298-303.

doi - McGinn S, White PD. Acute cor pulmonarly resulting from pulmonary embolism. JAMA 1935;104:1473-1780.

doi - Hubloue I, Schoors D, Diltoer M, Van Tussenbroek F, de Wilde P. Early electrocardiographic signs in acute massive pulmonary embolism. Eur J Emerg Med. 1996;3(3):199-204.

doi pubmed - Weber DM, Phillips JH, Jr. A re-evaluation of electrocardiographic changes accompanying acute pulmonary embolism. Am J Med Sci. 1966;251(4):381-398.

doi pubmed - Stein PD, Dalen JE, McIntyre KM, Sasahara AA, Wenger NK, Willis PW, 3rd. The electrocardiogram in acute pulmonary embolism. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1975;17(4):247-257.

doi - Lui CY. Acute pulmonary embolism as the cause of global T wave inversion and QT prolongation. A case report. J Electrocardiol. 1993;26(1):91-95.

doi - Lynch RE, Stein PD, Bruce TA. Leftward shift of frontal plane QRS axis as a frequent manifestation of acute pulmonary embolism. Chest. 1972;61(5):443-446.

doi pubmed - Rodger M, Makropoulos D, Turek M, Quevillon J, Raymond F, Rasuli P, Wells PS. Diagnostic value of the electrocardiogram in suspected pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86(7):807-809, A810.

- Petruzzelli S, Palla A, Pieraccini F, Donnamaria V, Giuntini C. Routine electrocardiography in screening for pulmonary embolism. Respiration. 1986;50(4):233-243.

doi pubmed - Manganelli D, Palla A, Donnamaria V, Giuntini C. Clinical features of pulmonary embolism. Doubts and certainties. Chest. 1995;107(1 Suppl):25S-32S.

doi pubmed - Ferrari E, Imbert A, Chevalier T, Mihoubi A, Morand P, Baudouy M. The ECG in pulmonary embolism. Predictive value of negative T waves in precordial leads—80 case reports. Chest. 1997;111(3):537-543.

doi pubmed - Turner RW. Clinical electrocardiography in general practice. I. The genesis of the electrocardiogram. Practitioner. 1962;188:141-144.

- Chou T. Electrocardiography in clinical practice. 2nd edn. Orlando, FL: Grune Stratton; 1986:309-317.

pubmed - Livaditis IG, Paraschos M, Dimopoulos K. Massive pulmonary embolism with ST elevation in leads V1-V3 and successful thrombolysis with tenecteplase. Heart. 2004;90(7):e41.

doi pubmed - Sokolov M, Katz LN, Muscovitz AN. The electrocardiogram in pulmonary embolism. Am Heart J 1940;19:166-184.

doi - Stein PD, Terrin ML, Hales CA, Palevsky HI, Saltzman HA, Thompson BT, Weg JG. Clinical, laboratory, roentgenographic, and electrocardiographic findings in patients with acute pulmonary embolism and no pre-existing cardiac or pulmonary disease. Chest. 1991;100(3):598-603.

doi pubmed - Kucher N. Catheter embolectomy for acute pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2007;132(2):657-663.

doi pubmed - Kearon C, Kahn SR, Agnelli G, Goldhaber S, Raskob GE, Comerota AJ. Antithrombotic therapy for venous thromboembolic disease: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):454S-545S.

- Koning R, Cribier A, Gerber L, Eltchaninoff H, Tron C, Gupta V, Soyer R, et al. A new treatment for severe pulmonary embolism: percutaneous rheolytic thrombectomy. Circulation. 1997;96(8):2498-2500.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.