| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 5, Number 2, February 2014, pages 66-72

Quiescent Crohn’s Disease in Clinical Remission With 6-Mercaptopurine: A Breeding Ground for CMV Pneumonia as Part of a Viral Infection Domino

George Panosa, e, Eftychia Polyzogopouloua, Karolina Akinosogloua, Dionysios C Watsona, George Theocharisb, Fotini Paliogiannic, Paraskevi Chrad, Vasiliki Nikolopouloub

aInfectious Diseases Section, Department of Internal Medicine, Patras University General Hospital, Patras, Greece

bGastroenterology Department, Patras University General Hospital, Patras, Greece

cDepartment of Microbiology, School of Medicine, University of Patras, Patras, Greece

dDepartment of Microbiology, Korgialenio-Benakio Hospital, Athens, Greece

eCorresponding author: George Panos, Infectious Diseases Section, Department of Internal Medicine, Patras University General Hospital, 26500 Patras, Greece

Manuscript accepted for publication September 23, 2013

Short title: CMV/Adenovirus Co-infection

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc1499w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is frequently associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). CMV pneumonitis has been reported infrequently in patients with IBD, while there has been one such report in a patient with quiescent Crohn’s disease (CD) under long-term immunosuppressant treatment with 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP). We present an unusual case of a 24-year-old male, with fistulized CD in clinical remission under 6-MP, who presented with fever and increased seropurulent fistulae effusion. Shortly after admission, he presented nonproductive cough, pancytopenia, elevated serum aminotransferases, hypoxemia and bilateral pulmonary reticulonodular infiltrates expanding from basal bronchopulmonary segments towards the hila. Positive CMV IgM/IgG, pp65 antigen and CMV-PCR confirmed the diagnosis of CMV pneumonitis. Enterococcus faecium and faecalis were also separately isolated from cultures of two different, concurrent enterocutaneous fistulae. Successful treatment included antiviral and appropriate antibiotic therapy. A subsequent adenovirus co-infection in this patient, demonstrating a viral domino phenomenon, illustrates the difficulty of establishing a final diagnosis in a complex case.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease; Adenovirus; Diagnosis; Treatment; Coxiella burnetti; Immunosuppression

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a frequent cause of morbidity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), whose mainstay medical treatment approach involves varying degrees of immunosuppressive therapy [1]. CMV pneumonitis is an unpredictable, life-threatening infection especially in immunocompromised hosts [2, 3]. There have been 13 published cases of IBD complicated by CMV pneumonitis, 10 of which were in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) [4]. Of these 10, five were on steroid treatment (50%), and all were on various combinations of mesalazine (5-ASA), azathioprine, cyclosporine A and 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) [4]. These cases are in line with studies of opportunistic infection risk in IBD patients, which has been linked to treatment with immunosuppressive medications (odds ratio (OR): 2.9; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.5-5.3) [5].

We report a case of CMV pneumonitis complicating quiescent CD, in a patient treated with 6-MP. Furthermore, this case describes a sequential infection with adenovirus (ADV) following the diagnosis of CMV pneumonitis (“domino” effect), an aspect of infection in immunocompromised individuals that should be considered.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 24-year-old male with quiescent CD, presented with a 4-day history of fever (< 39 °C), rigors and fatigue, while he also reported an increase in seropurulent fluid effusing from two known fistulae located in his right lower abdominal quadrant. His past medical history was significant for CD of the terminal ileum, as diagnosed histologically 3 years prior. His treatment over the 6 months preceding admission consisted of 6-MP, and occasional corticosteroids.

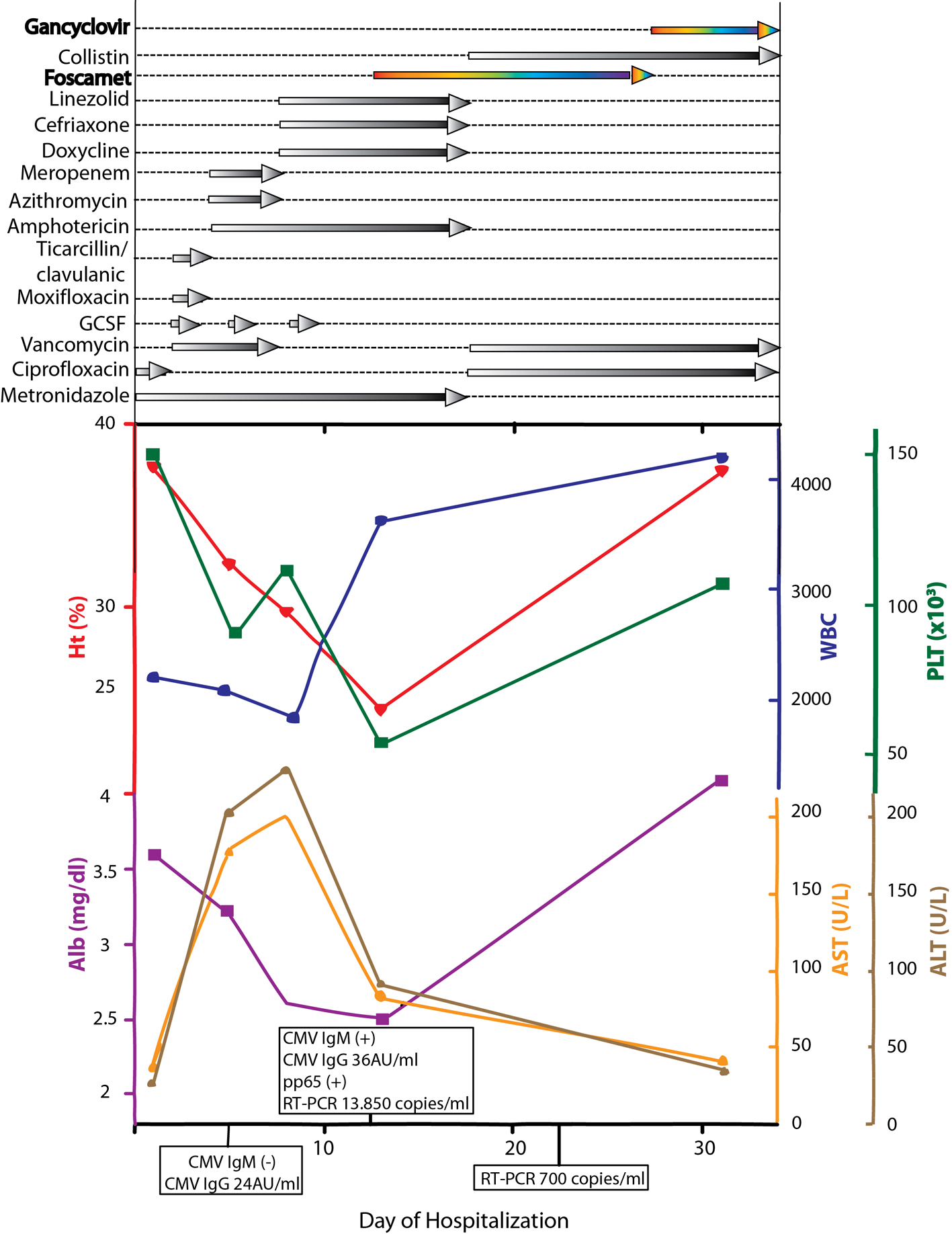

On admission, the patient was ill-looking, with a blood pressure of 110/70 mmHg, heart rate of 68 beats/min and an axillary temperature of 38.6 °C. Clinical examination was significant for mild splenomegaly and seropurulent effusion oozing from the fistulae. Laboratory tests (Fig. 1) were significant for increased lactate dehydrogenase (449 IU/L) and C-reactive protein (11.8 mg/dL). Electrocardiogram, chest X-ray (CXR) and abdominal CT were unrevealing.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Schematic representation of lab values, CMV serology and treatment regimens through the course of disease. |

After blood and fistulae culture samples were obtained, the patient was empirically put on ciprofloxacin 400 mg bid iv and metronidazole 500 mg tid iv (Fig. 1). Twenty-four hours later, white blood cell count declined (1.3 × 109/L), and granulocyte colony stimulating factor was started, in order to manage a supposed bone marrow suppression due to 6-MP.

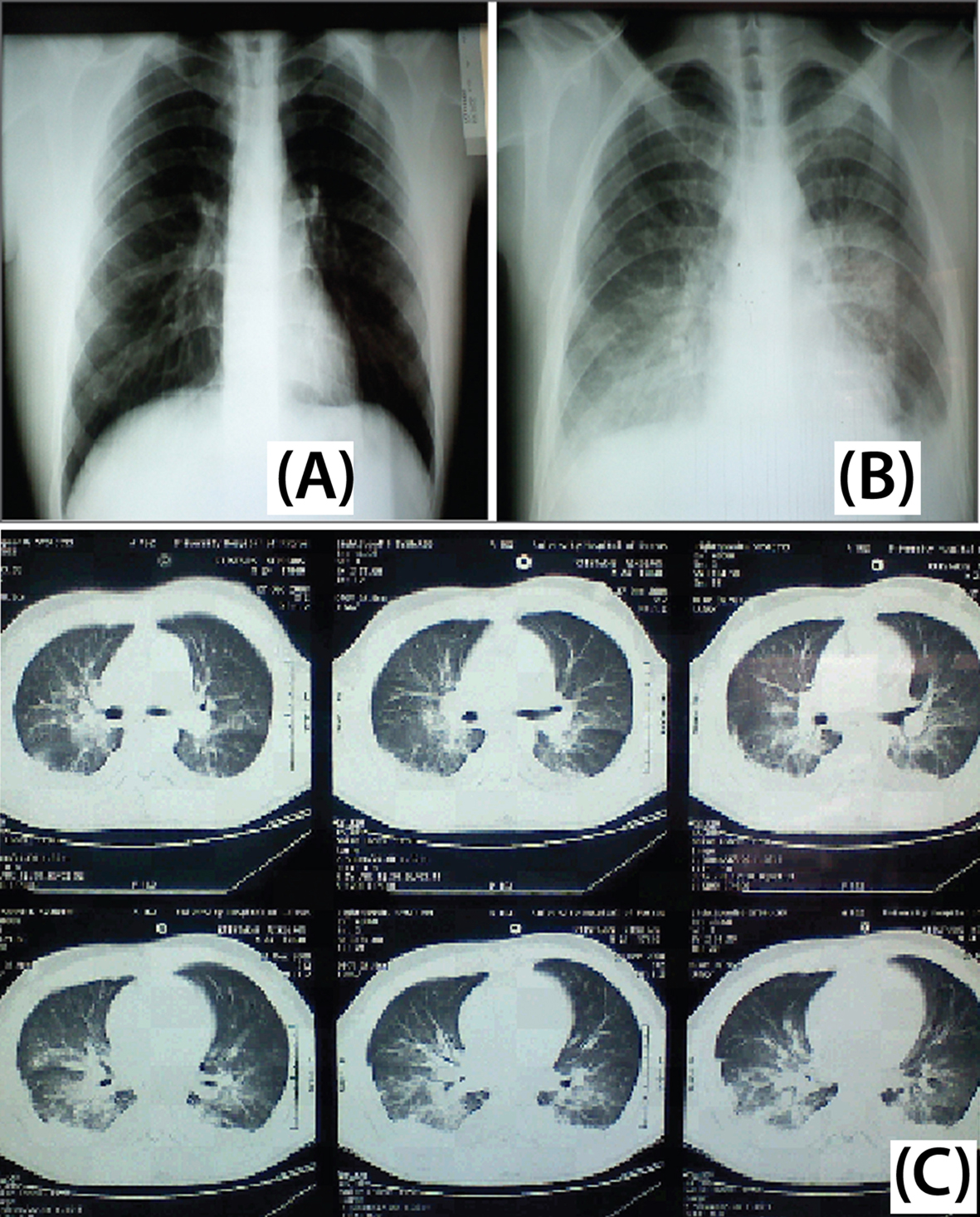

Over the next 5 days, the patient’s condition worsened. Fever persisted (≤ 41 °C), he developed nonproductive cough and bilateral lung base crackles could be heard on auscultation. Repeat CXR revealed reticulo-micronodular infiltrates of the right lung base (Fig. 2A), and subsequent chest CT confirmed a bilateral ground glass appearance and small right pleural effusion. Significant pancytopenia and markedly elevated liver function tests, and mild hypoxemia were present. The initial viral serology tests performed on day 3 (including CMV, Coxsackie, EBV, hepatitis A/B/C viruses, HIV, HSV1/2 and VZV), and serology tests for M. pneumoniae, Toxoplasma and Leptospira, came back negative. Bronchoscopy showed no signs of inflammation, while Gram, Ziehl-Nielsen, PCP-silver stain were negative, as were cultures for common and opportunistic pathogens.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Patient imaging studies. (A) Chest X-ray on day 5. Reticulo-micronodular infiltrates at the right lung base. (B) Chest X-ray on day 12. Bilateral reticulonodular infiltrates expanding from basal bronchopulmonary segments towards the hila and upper lobes. (C) Chest CT scan on day 12. Extensive central bilateral infiltrates, including atelectatic lesions and pleural effusions are depicted bilaterally. |

Based on clinical examination and given the underlying IBD and 6-MP immunosuppressant therapy, current differential diagnosis considered etiologies of abdominal infection leading to the enterocutaneous fistulae copiously effusing seropurulent fluid, such as E. coli, Enterococci and Bacteroides spp. Respiratory findings were tentatively attributed to a possible atypical pulmonary infection (Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae and Legionella pneumophila). Antibiotic therapy was changed to cover the most likely causative pathogens, while low pulse and borderline QT-prolongation (QTc: 0.442 sec) despite the patient’s high temperature, was attributable to the use of moxifloxacin (which was subsequently discontinued).

On day 8 following admission, the patient’s respiratory status further deteriorated (arterial blood gases, on room air: pH 7.44, pO2 54 mmHg, pCO2 23 mmHg, HCO3 17 mEq/L), and continuous positive airway pressure was introduced to maintain O2 saturation > 90%. At this time, Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis (both susceptible to vancomycin and teicoplanin) were respectively isolated from the two separate enterocutaneous fistula cultures taken during initial assessment. New laboratory serology was also positive for Coxiella IgM and rheumatoid factor (104 IU/mL; reference range < 20 IU/mL).

Given the temperature elevation, accompanying severe hypoxemia, reticulo-micronodular infiltrates at the right lung base, elevated serum transaminases, pancytopenia, an elevated RF, and positive C. burnetti IgM antibodies, the differential diagnosis included viral pulmonary infections, along with atypical pneumonia (M. pneumoniae, C. burnetti pneumonia, non-icterohemorrhagic leptospirosis, Chlamydophila pneumoniae and Ricketsiae). Thus, the therapeutic scheme was switched to doxycycline 200 mg uid per os, ceftriaxone 2 g qd iv, linezolid 600 mg bid iv (to enhance the therapeutic effect in abdominal tissue and fistulae) and metronidazole 500 mg tid iv; amphotericin 320 mg/day was continued to cover against possible fungal superinfection due to prolonged hospitalization and antibiotic use. Intravenous immunoglobulin 400 mg/kg/day was also initiated as compassionate treatment of a possible viral illness for which no confirmatory results were available, given that the patient did not demonstrate signs of improvement. Furthermore, based on the presence of pancytopenia, positive C. burnetti serology and RF (which can be false-positive in systemic CMV infection, due to rosette formation from viral-specific IgM antibodies), we were on alert for evolution of radiologic findings, in favor of an underlying CMV pneumonitis [6, 7].

Indeed, as the patient’s condition persisted, a repeat CXR at day 12 showed bilateral ascending reticulonodular infiltrates expanding from basal bronchopulmonary segments (from the costophrenic angles) towards the hila and upper lobes (Fig. 2B). Chest CT scan confirmed extensive central bilateral infiltrates, including atelectasic lesions and pleural effusions (Fig. 2C). The above clinical, laboratory and radiologic findings were strongly suggestive of CMV pneumonitis; thus, intravenous foscarnet (6 g bid/d) was initiated. Foscarnet was selected over ganciclovir, due to existing pancytopenia and effectiveness against possible resistant CMV strains [8]. Therapy to cover for atypical pneumonia was continued until a definitive diagnosis could be reached. Additionally, clindamycin 600 mg qid iv and primaquine were prescribed to cover against a possible emerging superinfection with PCP, since CMV and PCP commonly co-exist in immunocompromised hosts [2, 9]; only the former was initiated due to non-availability of primaquine.

Within 48 h, serum laboratory results showing CMV IgM(+)/IgG(+), pp65 antigen(+) and CMV-PCR 13,850 copies/mL were obtained confirming the clinical diagnosis of CMV pulmonary infection (Fig. 1).

However, after 5 days of appropriate antiviral therapy, the patient remained febrile, even as the purulent effusion from the fistulae ceased. Thus, this round of differential diagnosis included hospital acquired infection following bronchoscopy, infection with a resistant CMV strain, ADV co-infection, or drug-related fever. White blood cell count exhibited an increase at 6.3 × 109/L, despite persisting anemia and thrombocytopenia. Antibacterial coverage was altered to cover against frequent hospital acquired pathogens of our institution, and linezolid was switched back to vancomycin in order to avoid further thrombocytopenia.

Over the next 2 weeks, the patient’s condition markedly improved. However, the ADV antibody screen came back positive (IgM 28.6 AU (ref. range < 11 AU) and IgG 41.6 AU (ref. range < 11 AU)). Thus, fever was attributed to concomitant ADV infection. At this point, given the patient’s restored blood count, persisting hypokalemia and possible effectiveness against ADV (based on in vitro susceptibility [10]), antiviral medication was switched to gancyclovir 400 mg bid iv. Finally, the patient was discharged in good health on day 34, having completed 21 days of antiviral therapy.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

CMV in CD most frequently manifests as colitis [11]. CMV pneumonitis has been reported in 10 CD patients, as reviewed by Cascio et al (2012), while it is rarer in ulcerative colitis [4, 12-20]. Hookey et al reported a similar case to the presented patient, where a 19-year-old student with quiescent CD under therapy with 6-MP, developed CMV pneumonitis with a favorable outcome [21]. In a later case report, van Langerberg et al also noted a patient with quiescent CD under azathioprine presenting with persistent CMV respiratory infection, further complicated with hemophagocytic syndrome, and finally resolving under ganciclovir and anti-MAP (Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis) therapy [22]. These two cases were diagnosed with CMV pneumonitis while CD was in remission, similar to our report.

Immunosuppressant agents such as thiopurines (AZA and 6-MP) induce myelotoxicity in patients with IBD with an incidence rate of 4-7%, most frequently during the first months following initiation of therapy [23, 24]. It seems that the incidence of infections in this population, due to AZA/6MP-induced myelotoxicity is quite similar (6.5%) [24]. Toruner et al have shown that use of AZA/6MP for IBD is significantly associated with increased risk for opportunistic infection (OR 3.8; 95%CI 2.0-7.0). Interestingly, AZA/6MP were most commonly related to opportunistic viral infections such as VZV, HSV, EBV and CMV, attributable to compromise of T-lymphocytic antiviral activity [5]. We also present a possible association with confirmed ADV infection in the patient.

Multiple tests can be employed to diagnose CMV infection. Histology/cytology has long been the cornerstone of diagnosis, since cytomegalic intranuclear (owl’s eye) inclusions in tissue are pathognomonic for CMV infection [25]. Rapid CMV culture (shell vial culture, e.g. of blood samples) has largely replaced this method, along with conventional culture, as a more practical choice with reduced reporting time and increased sensitivity [26-29]. Blood culture has high specificity of 89-100%, but a still low sensitivity compared to antigen (pp65) and PCR tests, which are now widely employed [30, 31]. Antigen detection of virus protein pp65 in circulating leukocytes provides high sensitivity and specificity in CMV diagnosis; however, skilled personnel is required, and it is of limited value when the patient is leukopenic [31, 32]. Real-time PCR to detect CMV DNA is a quantitative technique with great sensitivity, which provides a good estimate of the systemic viral load and correlates well with pp65 antigenemia and clinical course [32]. Of note, the variable subset of immunocompromised patients (e.g. liver transplant, solid organ transplant, stem cell recipients, HIV) requires for different levels of measured viral copies/mL to be set for each group as cut-offs that determine infection status, hence complicating diagnosis. Although serologic tests also have relatively high sensitivity and specificity [33], they were not helpful in this case with respect to early virus detection, since 7 days following the onset of symptoms CMV IgM antibodies remained negative. Possible explanations for this include: 1) antibody measurement at an early stage of the course of infection and 2) inability of the immunocompromised host to mount an adequate IgM response. A delay in the culmination of the antibody response has been previously described in immunocompromised individuals infected by CMV [34].

Commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, indirect fluorescent antibody test and complement fixation test may show false-positive results or cross-reactivity when samples are positive for rheumatoid factor (RF) [35]. The issue of cross-reactivity between infections, especially when clinical manifestations are similar remains to be further resolved. Samples from patients infected with Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, Legionella, Leptospira, and Coxiella burnetti are frequently RF-positive [36]. Several studies [14, 37-42] imply cross-reactivity, while in certain cases the persistence of antibody from previous infection cannot safely be ruled out [43]. A combined IgM and IgA determination method for C. burnetti has been shown to improve the specificity in the diagnosis of acute Q fever with no cross-reactivity with the sera of patients with CMV and Ebstein-Barr infections, although cross-reactivity was observed with M. pneumoniae and Bordetella pertussis infections [42]. In our case, by utilizing a series of methods we confirmed the clinical diagnosis and monitored therapeutic efficacy. Interestingly, CMV viral load estimated by real-time PCR at the time of diagnosis was 13,850 copies/mL, and was markedly reduced to 700 copies/mL following 11 days of antiviral therapy (Fig. 1).

ADV infections are most commonly reported in the transplant population, particularly in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell recipients, reaching an incidence of 5-89% [44-47]. Mortality rates associated with ADV infection among transplant recipients range from 2 to 70% [47]. ADV co-infection is common with Candida, CMV and bacterial infection [48]. To our knowledge, this is the first case of ADV infection to be reported in the presence of concomitant CD and developing CMV pneumonitis. The presentation of a “domino” ADV infection in a clinically improving, albeit persistently febrile, patient was in accordance with our experience in other immunosuppressed patients.

Conclusion

The presented patient demonstrates the difficulty of setting the final diagnosis in a complicated case. Early diagnosis of CMV pneumonitis requires a high index of suspicion in deteriorating febrile patients, in the presence of pancytopenia, elevated serum liver enzymes, hypoxemia and ascending-bilateral chest infiltrates, especially when accompanied by positive rheumatoid factor and/or C. burnetti serology. Diagnostic confirmation of CMV infection (virus-specific IgM antibodies, pp65 and PCR) may come later on, making the early recognition/management of respective cases an important approach to consider, especially among immunocompromised patients. Finally, among the immunocompromised population, a “domino” effect in the emergence of consecutive infections should be anticipated; this calls for the treating physician to be alert and astute so that new infections are promptly diagnosed and managed.

Declaration of Interests

No funding was received. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

| References | ▴Top |

- Garrido E, Carrera E, Manzano R, Lopez-Sanroman A. Clinical significance of cytomegalovirus infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(1):17-25.

doi pubmed - Ljungman P. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia: presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Respir Infect. 1995;10(4):209-215.

pubmed - de Maar EF, Verschuuren EA, Harmsen MC, The TH, van Son WJ. Pulmonary involvement during cytomegalovirus infection in immunosuppressed patients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2003;5(3):112-120.

doi pubmed - Cascio A, Iaria C, Ruggeri P, Fries W. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis. 2012;16(7):e474-479.

doi pubmed - Toruner M, Loftus EV

Jr , Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Orenstein R, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF,et al . Risk factors for opportunistic infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(4):929-936.

doi pubmed - Field PR, Mitchell JL, Santiago A, Dickeson DJ, Chan SW, Ho DW, Murphy AM,

et al . Comparison of a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with immunofluorescence and complement fixation tests for detection of Coxiella burnetii (Q fever) immunoglobulin M. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38(4):1645-1647.

pubmed - el-Mekki A, Deverajan LV, Soufi S, Strannegard O, al-Nakib W. Specific and non-specific serological markers in the screening for congenital CMV infection. Epidemiol Infect. 1988;101(3):495-501.

doi pubmed - Bacigalupo A, Boyd A, Slipper J, Curtis J, Clissold S. Foscarnet in the management of cytomegalovirus infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2012;10(11):1249-1264.

doi pubmed - Williams AJ, Duong T, McNally LM, Tookey PA, Masters J, Miller R, Lyall EG,

et al . Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and cytomegalovirus infection in children with vertically acquired HIV infection. AIDS. 2001;15(3):335-339.

doi pubmed - Taylor DL, Jeffries DJ, Taylor-Robinson D, Parkin JM, Tyms AS. The susceptibility of adenovirus infection to the anti-cytomegalovirus drug, ganciclovir (DHPG). FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1988;49:337-341.

doi - Kandiel A, Lashner B. Cytomegalovirus colitis complicating inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(12):2857-2865.

doi pubmed - Papadakis KA, Tung JK, Binder SW, Kam LY, Abreu MT, Targan SR, Vasiliauskas EA. Outcome of cytomegalovirus infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(7):2137-2142.

doi pubmed - Piton G, Dupont-Gossart AC, Weber A, Herbein G, Viennet G, Mantion G, Carbonnel F. Severe systemic cytomegalovirus infections in patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis treated by an oral microemulsion form of cyclosporine: report of two cases. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008;32(5 Pt 1):460-464.

doi pubmed - Williams JC, Hoover TA, Waag DM, Banerjee-Bhatnagar N, Bolt CR, Scott GH. Antigenic structure of Coxiella burnetii. A comparison of lipopolysaccharide and protein antigens as vaccines against Q fever. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;590:370-380.

doi pubmed - Sijpkens YW, Allaart CF, Thompson J, van't Wout J, Kluin PM, den Ottolander GJ, Bieger R. Fever and progressive pancytopenia in a 20-year-old woman with Crohn's disease. Ann Hematol. 1996;72(4):286-290.

doi pubmed - Alderson JW, Van Dinter TG

Jr , Opatowsky MJ, Burton EC. Disseminated aspergillosis following infliximab therapy in an immunosuppressed patient with Crohn's disease and chronic hepatitis C: a case study and review of the literature. MedGenMed. 2005;7(3):7.

pubmed - de Boer NK, van Bodegraven AA, de Graaf P, van der Hulst RW, Zoetekouw L, van Kuilenburg AB. Paradoxical elevated thiopurine S-methyltransferase activity after pancytopenia during azathioprine therapy: potential influence of red blood cell age. Ther Drug Monit. 2008;30(3):390-393.

doi pubmed - Wolschke C, Fiedler W, Habermann RC, Janka-Schaub GE, Kluge S. [28-year old female patient with respiratory insufficiency, elevated liver enzymes, pancytopenia and fever]. Internist (Berl). 2010;51(11):1434-1438.

doi pubmed - N'Guyen Y, Baumard S, Salmon JH, Lemoine L, Leveque N, Servettaz A, Jaussaud R,

et al . Cytomegalovirus associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in patients suffering from Crohn's disease treated by azathioprine: a series of four cases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(9):E116-118.

pubmed - Presti MA, Costantino G, Della Torre A, Belvedere A, Cascio A, Fries W. Severe CMV-related pneumonia complicated by the hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytic (HLH) syndrome in quiescent Crohn's colitis: harmful cure?. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(11):E145-146.

doi pubmed - Hookey LC, Depew W, Boag A, Vanner S. 6-mercaptopurine and inflammatory bowel disease: hidden ground for the cytomegalovirus. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17(5):319-322.

pubmed - van Langenberg DR, Morrison G, Foley A, Buttigieg RJ, Gibson PR. Cytomegalovirus disease, haemophagocytic syndrome, immunosuppression in patients with IBD: 'a cocktail best avoided, not stirred'. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5(5):469-472.

doi pubmed - Chaparro M, Ordas I, Cabre E, Garcia-Sanchez V, Bastida G, Penalva M, Gomollon F,

et al . Safety of thiopurine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: long-term follow-up study of 3931 patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(7):1404-1410.

doi pubmed - Gisbert JP, Gomollon F. Thiopurine-induced myelotoxicity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(7):1783-1800.

doi pubmed - Rasing LA, De Weger RA, Verdonck LF, van der Bij W, Compier-Spies PI, De Gast GC, Van Basten CD,

et al . The value of immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization in detecting cytomegalovirus in bone marrow transplant recipients. APMIS. 1990;98(6):479-488.

doi pubmed - Hebart H, Muller C, Loffler J, Jahn G, Einsele H. Monitoring of CMV infection: a comparison of PCR from whole blood, plasma-PCR, pp65-antigenemia and virus culture in patients after bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;17(5):861-868.

pubmed - Crumpacker CS. Cytomegalovirus. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles an Practice of Infectious Diseases. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Churchhill Livingstone; 2000:1586-1599.

- Murray BM, Amsterdam D, Gray V, Myers J, Gerbasi J, Venuto R. Monitoring and diagnosis of cytomegalovirus infection in renal transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8(9):1448-1457.

pubmed - Shuster EA, Beneke JS, Tegtmeier GE, Pearson GR, Gleaves CA, Wold AD, Smith TF. Monoclonal antibody for rapid laboratory detection of cytomegalovirus infections: characterization and diagnostic application. Mayo Clin Proc. 1985;60(9):577-585.

doi - Ross SA, Novak Z, Pati S, Boppana SB. Overview of the diagnosis of cytomegalovirus infection. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2011;11(5):466-474.

doi pubmed - de la Hoz RE, Stephens G, Sherlock C. Diagnosis and treatment approaches of CMV infections in adult patients. J Clin Virol. 2002;25(Suppl 2):S1-12.

doi - Drew WL. Laboratory diagnosis of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in immunocompromised patients. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20(4):408-411.

doi pubmed - Grazia Revello M, Percivalle E, Zannino M, Rossi V, Gerna G. Development and evaluation of a capture ELISA for IgM antibody to the human cytomegalovirus major DNA binding protein. J Virol Methods. 1991;35(3):315-329.

doi - Dussaix E, Chantot S, Harzic M, Grangeot-Keros L. CMV-IGG avidity and CMV-IGM concentration in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients. Pathol Biol (Paris). 1996;44(5):405-410.

- Soliman AK, Botros BA, Morrill JC. Solid-phase immunosorbent technique for rapid detection of Rift Valley fever virus immunoglobulin M by hemagglutination inhibition. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26(9):1913-1915.

pubmed - Vardi M, Petersil N, Keysary A, Rzotkiewicz S, Laor A, Bitterman H. Immunological arousal during acute Q fever infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30(12):1527-1530.

doi pubmed - Dwyer DE, Gibbons VL, Brady LM, Cunningham AL. Serological reaction to Legionella pneumophila group 4 in a patient with Q fever. J Infect Dis. 1988;158(2):499-500.

pubmed - Hoover TA, Vodkin MH. Cloning and expression of Coxiella Burnetii DNA. In: Williams JC, Thompson TA, eds. Q Fever: The Biology of Coxiella Burnetii. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1991:283-310.

- Vodkin MH, Williams JC. A heat shock operon in Coxiella burnetti produces a major antigen homologous to a protein in both mycobacteria and Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170(3):1227-1234.

pubmed - Hoffman PS, Houston L, Butler CA. Legionella pneumophila htpAB heat shock operon: nucleotide sequence and expression of the 60-kilodalton antigen in L. pneumophila-infected HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 1990;58(10):3380-3387.

pubmed - Stallman ND, Allan BC. A survey of antibodies to Mycoplasma pneumoniae in Queensland. Med J Aust. 1970;1(16):800-802.

pubmed - Devine P, Doyle C, Lambkin G. Combined determination of Coxiella burnetii-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgA improves specificity in the diagnosis of acute Q fever. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4(3):384-386.

pubmed - Winslow WE, Merry DJ, Pirc ML, Devine PL. Evaluation of a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of immunoglobulin M antibody in diagnosis of human leptospiral infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(8):1938-1942.

pubmed - Taniguchi K, Yoshihara S, Tamaki H, Fujimoto T, Ikegame K, Kaida K, Nakata J,

et al . Incidence and treatment strategy for disseminated adenovirus disease after haploidentical stem cell transplantation. Ann Hematol. 2012;91(8):1305-1312.

doi pubmed - Morfin F, Boucher A, Najioullah F, Bertrand Y, Bleyzac N, Poitevin-Later F, Bienvenu F,

et al . Cytomegalovirus and adenovirus infections and diseases among 75 paediatric unrelated allogeneic bone marrow transplant recipients. J Med Virol. 2004;72(2):257-262.

doi pubmed - George D, El-Mallawany NK, Jin Z, Geyer M, Della-Latta P, Satwani P, Garvin JH,

et al . Adenovirus infection in paediatric allogeneic stem cell transplantation recipients is a major independent factor for significantly increasing the risk of treatment related mortality. Br J Haematol. 2012;156(1):99-108.

doi pubmed - Echavarria M. Adenoviruses in immunocompromised hosts. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(4):704-715.

doi pubmed - Khoo SH, Bailey AS, de Jong JC, Mandal BK. Adenovirus infections in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients: clinical features and molecular epidemiology. J Infect Dis. 1995;172(3):629-637.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.