| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 4, Number 12, December 2013, pages 775-779

Infiltrative Disease in Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy: Giant Cell Myocarditis Leading to Fulminant Myocarditis

Jeffrey Chana, c, Eric Adlerb

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, University of California San Diego, UC San Diego Medical Center, 402 Dickenson Street, San Diego, CA 92103, USA

bDepartment of Cardiology, University of California San Diego, UC San Diego Medical Center, 402 Dickenson Street, San Diego, CA 92103, USA

cCorresponding author: Jeffrey Chan, Department of Internal Medicine, University of California San Diego, UC San Diego Medical Center, 402 Dickenson Street, San Diego, CA 92103, USA

Manuscript accepted for publication September 23, 2013

Short title: Infiltrative Disease

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/jmc1502w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Giant cell myocarditis (GCM) is a rare cause of fulminant myocarditis associated with rapid onset severe heart failure. We report here a case of infiltrative cardiomyopathy in an atypical age group to highlight the spectrum of a rare disease and the appropriate clinical considerations in its diagnosis and management.

Keywords: Giant cell myocarditis; Cardiomyopathy; Ventricular tachycardia

| Introduction | ▴Top |

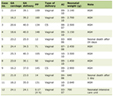

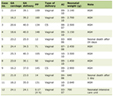

Myocarditis is clinically and pathologically defined as “inflammation of the myocardium”. It is a general term that encompasses a broad spectrum of pathology that all contribute via different mechanisms to myocardial inflammation [1]. Giant cell myocarditis is one such cause of myocarditis. It is a rare disorder that results in progressive acute or subacute heart failure and is generally attributed to a T-lymphocyte-mediated inflammation of the heart muscle [2]. It is mostly a disease of young adults, with an average age of 37 and 48 as noted in two previously reported series. The most common early manifestations of this disease are heart failure, ventricular arrhythmias, and atrioventricular block [3-5]. The Giant Cell Myocarditis Study Group identified heart failure symptoms as the primary presentation in 75% of patients with giant cell myocarditis. Nonetheless, the clinical presentation of the disease still ranges from nonspecific symptoms of fever, myalgias, palpitations, or exertional dyspnea to full hemodynamic collapse. It is this diversity in clinical presentation that accounts for the unfortunate reality that even in experienced tertiary academic medical centers greater than 40% of cases escape detection when endomyocardial biopsy is not pursued. The condition is often rapidly fatal as it quickly deteriorates into fulminant myocarditis. Liberman et al created a broad classification system to assist clinicians in recognizing fulminant myocarditis as shown in Table 1 [6]. The classification divides myocarditis essentially into fulminant, subacute, chronic active, and chronic persistent subtypes. Patients with fulminant myocarditis, as in this case we report, present with acute, severe heart failure, and are often in cardiogenic shock requiring hemodynamic support [7].

Click to view | Table 1. Classification of Different Subtypes of Myocarditis |

Given their rarity, consideration of infiltrative etiologies such as giant cell myocarditis is often underemphasized in the evaluation of both known and new onset cardiomyopathy. Unfortunately, when not pursued simultaneously or systematically with traditional ischemic workups, this period of elapsed time before relevant workup is pursued compromises patient care as it delays the initiation of medical therapy.

We report here a case of giant cell myocarditis that continually worsened to fulminant myocarditis despite standard and aggressive hemodynamic support to illustrate the importance of considering infiltrative causes of cardiomyopathy even in uncommon age groups and the relevance of prompt cardiac biopsy for diagnostic workup.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 70-year-old woman with a history of COPD and diastolic heart failure presented with acutely decompensated HF and ventricular tachycardia (Vtach) that deteriorated into cardiogenic shock despite inotropic support. The patient was shopping when she first noticed palpitations without chest pain; upon presenting in the ED she was found to be in Vtach in the 170 s with systolic pressures in the 70 s. An echocardiogram demonstrated an ejection fraction of 23% with a dilated left ventricle and severely depressed right ventricular function. With systolic pressures in the 60 s despite maximum dose of neosynephrine and persistent Vtach, the patient was intubated and sent for an intra-aortic balloon pump, right/left heart catheterization, and coronary angiography. Hemodynamics (mmHg) from the catheterization showed a Mean RA of 17, RV 57/17, PA 59/29, PCWP 35, Fick CO 2.8, CI 1.5, AP 102/78, and LVEDP of 28. However, angiography demonstrated no coronary artery disease. Post-procedure, the patient was treated with vasopressin, neosynephrine, and dopamine for pressure support and amiodarone and lidocaine for Vtach. With concern that the patient’s persistent Vtach despite an IABP may have been secondary to the pro-arrhythmogenic medication, her inotropic therapy was titrated down with a plan for a left ventricular assist device (LVAD). Diagnostics performed included thyroid panels and a plan for a cardiac MRI but the patient became unstable necessitating the immediate placement of a VAD. Cardiac biopsy done during LVAD implantation on day 15 demonstrated mononuclear cell inflammation with multinucleated giant cells, widespread interstitial fibrosis, and inflammation with lymphoid nodules consistent with a diagnosis of giant cell myocarditis. Cellcept was started on day 15 but the patient continued to be hemodynamically unstable requiring increasing amounts of dobutamine, milrinone, and levophed, and worsening renal function requiring continuous renal replacement therapy. In addition to an increasing white blood cell counts, fevers, and worsening multi-organ failure, blood cultures at this time also demonstrated growth of gran negative rods. The patient unfortunately passed away on day 17.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

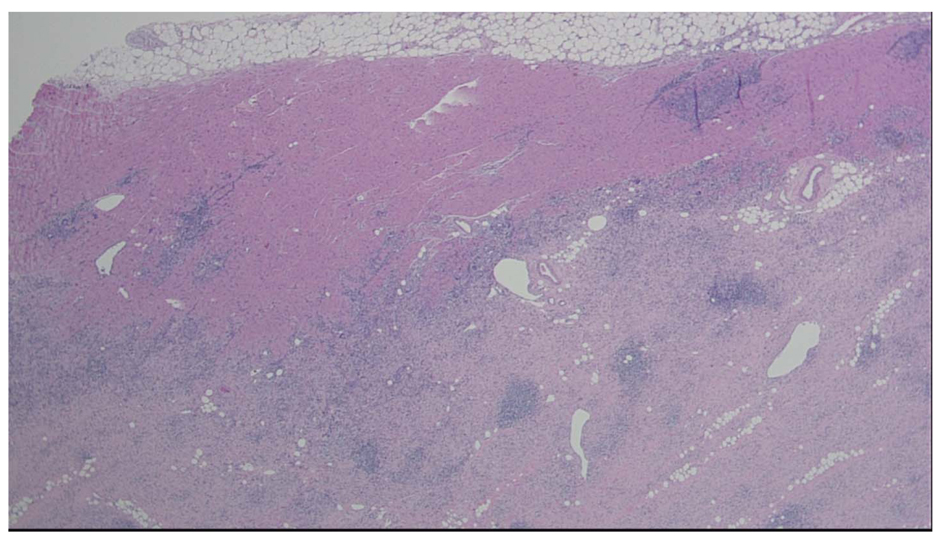

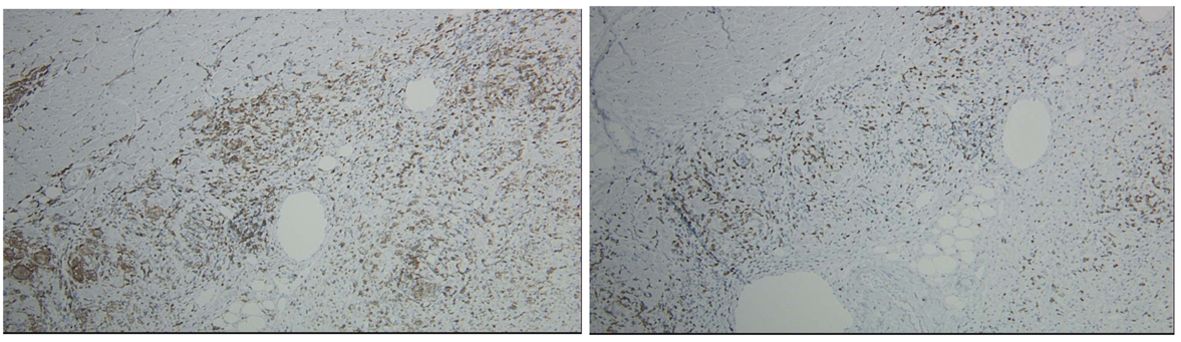

Giant cell myocarditis has been recognized as a rapidly fatal inflammatory cardiac disease that often progresses to death within days to months by causing a progressive decline in ventricular function. This case illustrates the importance of early consideration of infiltrative disorders in the etiology of acute onset HF exacerbation in both new and known HF patients even in atypical age groups. It emphasizes the value of prompt cardiac biopsy to definitively diagnose an infiltrative disease in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy (NICM). Fulminant myocarditis is a Class 1 indication for endomyocardial biopsy [8]. Cardiac biopsies generally demonstrate extensive necrosis and inflammation with lymphocytes, eosinophils, giant cells, and an absence of granulomas [9]. The presence of multinucleated giant cells on hematoxylin and eosin staining of endomyocardial biopsy samples is the pathologic hallmark of this entity as shown in Figures 1 and 2 from our own patient in this reported case. Although MRI is not sensitive enough to rule out GCM, it assists in the diagnosis by depicting areas of involvement and directing the necessary biopsy [10, 11]. MRI also aids in the exclusion of other types of cardiomyopathy and provides quantitative measures of right and left ventricular function for assessing disease progression and prognosis [12]. In fact data has increasingly suggested that a protocoled routine combination of both gadolinium enhanced cardiac MRI and FDG-PET alongside cardiac biopsy significantly improves detection rate.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Heart, apical core biopsy. Section of myocardial biopsy shows extensive myocardial necrosis and chronic inflammation with lymphocytes, eosinophils, and many giant cells. No granulomas are identified. Giant Cell Myocarditis 4 × H & E Stain |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Giant Cell Myocarditis 10 × CD4. Giant Cell Myocarditis 10 × CD8. Heart, apical core biopsy. CD4 and CD8 immunostains show a mixture of CD4 and CD8 positive T cells (CD4 > CD8). Histologic findings are consistent with diagnosis of giant cell myocarditis. Absence of granulomas with extensive necrosis and presence of eosinophils argue against the possibility of sarcoidosis. GMS, AFB stains are negative for fungi and acid fast bacilli. |

Current treatment for giant cell myocarditis involves immunosuppression. Studies suggest that immunosuppression may arrest the disease process in patients with GCM with clinical remission sufficient for survival free of transplantation if started promptly. Reports have indicated that treatment with high dose steroids combined with cyclosporine and azathioprine or cellcept could also be of benefit to patients. Cardiac transplantation is the treatment of choice for those who do not respond to a trial of immunosuppressive therapy. Unfortunately, the efficacy of treatment in fulminant myocarditis is only marginal. In the largest study to date of GCM, transplant free survival was 11%. Further, of the patients who did get cardiac transplantation, up to 25% had recurrent disease.

As with our patient, fulminant myocarditis has a limited differential diagnosis including GCM, necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis, sarcoidosis, peripartum cardiomyopathy, and acute myocardial infarction with GCM being the leading non-ischemic offender (Table 2). GCM is commonly associated with autoimmune disorders, thymomas, and drug hypersensitivity. Early evaluation with both appropriate imaging and biopsy allow for the differentiation of these etiologies as part of the initial evaluation for an infiltrative process in a patient with NICM.

Click to view | Table 2. Differential for Fulminant Myocarditis |

This fascinating case of giant cell myocarditis highlights the importance of the consideration of infiltrative etiologies in patients presenting with acute heart failure exacerbation even if not in the typical age range of 30 to mid 40 s. The patient presented with the classical GCM symptoms of biventricular failure and recurrent ventricular tachycardia on initial presentation. Additionally, her lack of risk factors and African American ethnicity additionally raised suspicion for infiltrative etiologies for acute decompensated heart failure. However, her presenting age of 70, lack of prior episodes of similar severe decompensation, and already known history of heart failure did not resemble the typical presentation of GCM induced cardiomyopathy. Studies have demonstrated some potential of immunosuppressive therapy in GCM, however, as in this patient’s case of decompensated fulminant myocarditis, the efficacy of steroids and immunosuppresion is only marginal. In such advanced stages of myocarditis, hemodynamic support is the priority. We present this case to not only re-familiarize clinicians with a rare diagnosis, but to emphasize the importance of considering obscure infiltrative disorders in cardiomyopathy even in atypical presentations to allow for early initiation of relevant biopsies and imaging if relevant in guiding immunosuppressive management and the priority of hemodynamic support in cases that have progressed to fulminant stages.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

| References | ▴Top |

- Magnani JW, Dec GW. Myocarditis: current trends in diagnosis and treatment. Circulation. 2006;113(6):876-890.

doi pubmed - Kandolin R, Lehtonen J, Salmenkivi K, Raisanen-Sokolowski A, Lommi J, Kupari M. Diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of giant-cell myocarditis in the era of combined immunosuppression. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(1):15-22.

doi pubmed - Cooper LT

Jr . Acute heart failure due to fulminant and giant cell myocarditis. Herz. 2006;31(8):767-770.

doi pubmed - Cooper LT

Jr , Berry GJ, Shabetai R. Idiopathic giant-cell myocarditis—natural history and treatment. Multicenter Giant Cell Myocarditis Study Group Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(26):1860-1866.

doi pubmed - Hari B, Peter O, Vikas KR, Robert WWB. Cardiac Sarcoidosis or Giant Cell Myocarditis?On Treatment Improvement of Fulminant Myocarditis as Demonstrated by Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Case Reports in Cardiology. 2012;2012

doi

doi - Sachin G, Markham DW, Drazner MH, Mammen PP. Fulminant Myocarditis. Nat-ClinPrac. 2008;5:693-706.

doi pubmed - McCarthy RE

3rd , Boehmer JP, Hruban RH, Hutchins GM, Kasper EK, Hare JM, Baughman KL. Long-term outcome of fulminant myocarditis as compared with acute (nonfulminant) myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(10):690-695.

doi pubmed - Cooper LT, Baughman KL, Feldman AM, Frustaci A, Jessup M, Kuhl U, Levine GN,

et al . The role of endomyocardial biopsy in the management of cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the European Society of Cardiology. Circulation. 2007;116(19):2216-2233.

doi pubmed - Uemura A, Morimoto S, Hiramitsu S, Kato Y, Ito T, Hishida H. Histologic diagnostic rate of cardiac sarcoidosis: evaluation of endomyocardial biopsies. Am Heart J. 1999;138(2 Pt 1):299-302.

doi - Okura Y, Dec GW, Hare JM, Kodama M, Berry GJ, Tazelaar HD, Bailey KR,

et al . A clinical and histopathologic comparison of cardiac sarcoidosis and idiopathic giant cell myocarditis. J Am Coll-Cardiol. 2003;41(2):322-329.

doi - Shonk JR, Vogel-Claussen J, Halushka MK, Lima JA, Bluemke DA. Giant cell myocarditis depicted by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2005;29(6):742-744.

doi pubmed - Tandri H, Saranathan M, Rodriguez ER, Martinez C, Bomma C, Nasir K, Rosen B,

et al . Noninvasive detection of myocardial fibrosis in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy using delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll-Cardiol. 2005;45(1):98-103.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.