| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 5, Number 6, June 2014, pages 366-368

Infective Endocarditis, Heart and Beyond

Sohail Iqbala, b, e, Rana Tahseen Ahmadb, Nouman Zahoor Ahmedc, Mureed Hussainc, Aftab Khanc, Muhammad Zubair Hanifd, Zulfiqar Alib

aColchester Hospital University Foundation Trust, CO4 5JL, Colchester, UK

bStepping Hill Hospital, Stockport, England, SK2 7JE, UK

cTameside General Hospital, Ashton Under Lyne, England, OL6 9RW, UK

dLinyi People’s Hospital, Linyi, Shandong University, Shandong, China

eCorresponding Author: Sohail Iqbal, Radiology Department, Colchester General Hospital, CO4 5JL, Colchester, UK

Manuscript accepted for publication February 18, 2014

Short title: Infective Endocarditis

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc1699w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Infective endocarditis has been a constant menace in human history with its debilitating consequences. The predisposing factors such as dental plaques/procedures and compromised valvular heart lesions contribute greatly in disease occurrence. Human commensals have been a source of infection. It manifests as combination of clinical sign and symptoms and mainly relies on echocardiographic findings and blood culture results. Trans-oesophageal echocardiography is superior in depicting vegetations on cardiac structures. We present three cases in two Manchester hospitals over a short span of time caused by Streptococci gordonii, agalactiae and Staphylococcus aureus.

Keywords: Infective endocarditis; Blood cultures; Echocardiography

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Infective endocarditis is a rare disease caused by normal body flora; particularly oral, gastrointestinal and genito-urinary commensals. Leaking or abnormal heart valves, previous valve surgery, metallic valves, uncorrected congenital cardiac anomalies, dental plaques, dental procedures, repeated gum and dental bleeding, and drug addiction are some of the predisposing factors for infective endocarditis. Infective endocarditis responds well to prolonged course of intravenous antibiotics in majority of cases; however, a few resistant/advanced cases may need surgical debridement of the plaques and replacement of affected valves. In about 20% cases the outcome proves to be fatal even after aggressive treatment.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Our first patient was a middle aged British white lady who presented with headache, fever, neck stiffness and sensation of being generally unwell. She developed intermittent fever associated with rigors and chills during her holidays in Europe. She also had nausea, malaise and joint pains without any rash. She was a known case of mitral regurgitation with leaky posterior leaflet. She underwent dental procedure for mild dental plaques and caries. On examination she had splinter haemorrhages, raised temperature and pan-systolic murmur at mitral area radiating to the axilla. C-reactive protein (CRP) and white cell count (WCC) were raised with mildly deranged liver function tests (LFTs). Three consecutive blood cultures revealed Streptococcus gordonii. Electrocardiogram was unremarkable. Trans-thoracic echocardiogram failed to demonstrate the vegetations; however, trans-oesophageal echocardiogram (TOE) demonstrated vegetations on aortic and pulmonary valves.

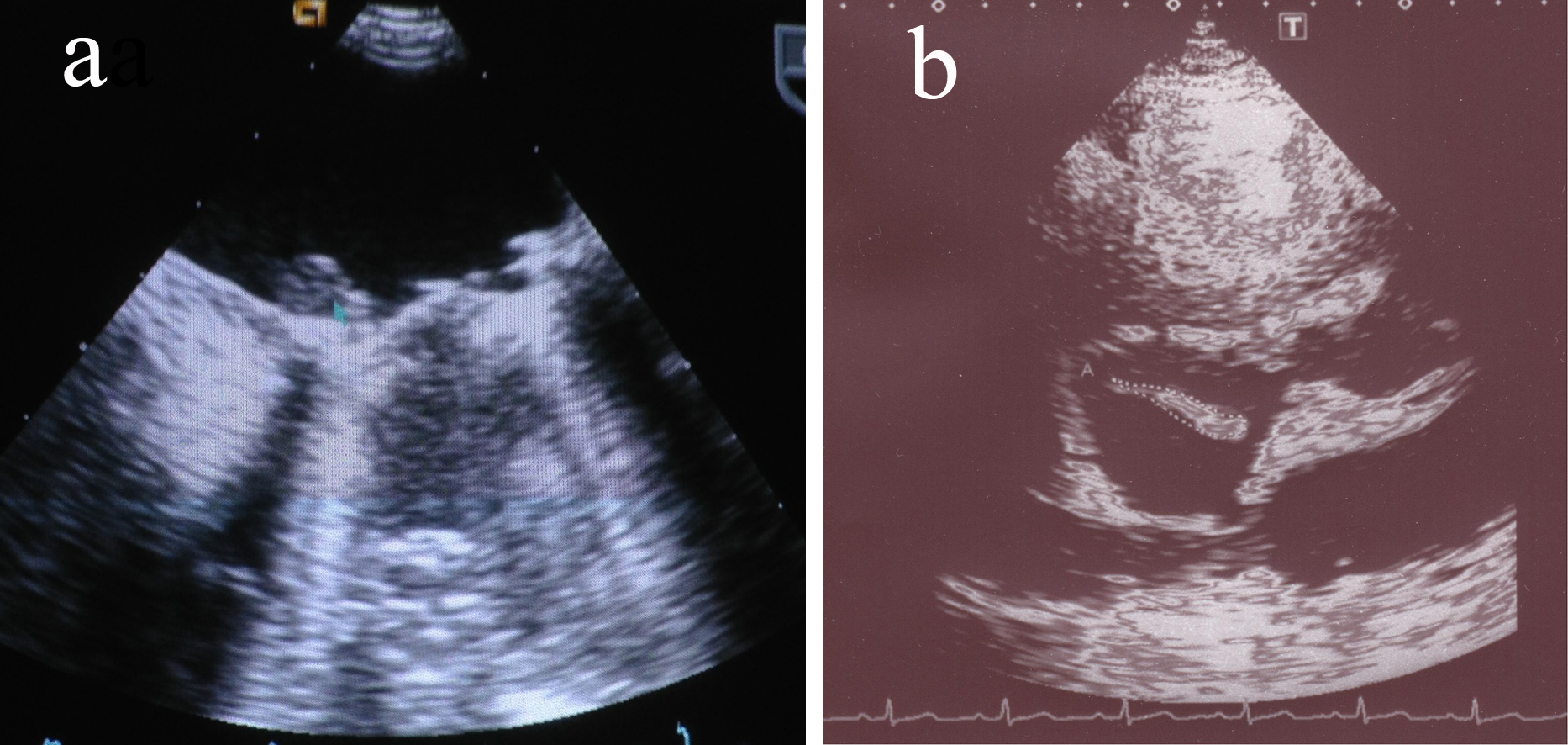

Second patient was a 33-year-old African drug-addict male with aortic and mitral valve prosthesis and history of tooth extraction 2 months ago. He came with high grade fever and chest pain and was found to have infective endocarditis. Culture was positive for Streptococcus agalactiae and viridans on three different occasions. TOE showed two dangling vegetations on prosthetic mitral valve (Fig. 1a).

Click for large image | Figure 1. (a) Thick sessile vegetation on mitral valve. (b) Large dangling vegetation on tricuspid valve. |

Third case was a 28-year-old English intravenous drug user lady with mixed valvular heart disease. She presented with high grade fever, chest pain and cough. She was found to have vegetations on tricuspid valve on TOE ultrasound (Fig. 1b). Blood culture was positive for Staphylococcus aureus. CT thorax showed multiple small cavitary lesions in both lungs, suggesting infective pulmonary emboli (Fig. 2).

Click for large image | Figure 2. CT chest depicting cavitary lesions representing septic emboli. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Infective endocarditis is a rare entity. Annual incidence in UK is reported to be 1.4 - 4 per 100,000 [1]. Male to female ratio is about 2.3:1 [2]. Drug addiction, valvular heart disease, prosthetic valves and pacemakers are predisposing factors. Dental plaques, dental procedures, bad oral hygiene and day to day trivial trauma are responsible for removal of oral flora and subsequent bacteremia. Bacteremia is considered to be the pathogenesis of infective endocarditis which leads to vegetation and abscess formation. It can result into valve leakage and aortic root weakening. The most commonly found bacteria are Streptococcus species including sanguis, gordonii, agalactiae, pneumoniae, oralis, mitis, beta-hemolytic group G, Staphylococcus aureus/epidermidis and diptheroids [3]. Hemophilus, Actinobacillus, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, Kingella (HACEK) [4], Coxiella burnetii, Chlamydia, Propionibacterium acnes, Mycobacteria, Bartonella henselae, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Tropheryma whippelii [5] along with fungi Candida, Aspergillus and Histoplasma are the rarely isolated organisms.

The Streptococcus viridans is followed by gordonii which is structurally related to sanguis species but environmentally is related to mutans/mitis sp. Streptococcus agalactiae is related to gastrointestinal tract and was previously known as Strep bovis. These bacteria form fibrin containing vegetations over the failing or metallic valves and devices like pacemakers and implantable defibrillators. Staphylococcus aureus is increasingly found in intravenous drug users and resides on right sided heart valves causing infective embolization [6].

Fever, headache, joint pains, backache, haematuria, loss of appetite, unexplained weight loss, new rashes, confusion, breathlessness and features suggestive of stroke are common clinical presentations. Clinical examination may reveal new onset murmur, new fingernail, skin and eye changes.

Diagnosis of the infective endocarditis is based upon Duke’s criteria. According to this diagnostic tool we look for two major, one major and three minor or five minor criteria [7] which are as follows. Major criteria: 1) Positive blood culture detecting typical organism in two separate cultures or persistently positive blood cultures, e.g. 3, > 12 h apart (or majority if ≥ 4); 2) Positive echocardiogram vegetation, abscess, dehiscence of prosthetic valve or new valvular regurgitation. Minor criteria: 1) Predisposition (cardiac lesion; IV drug user); 2) Fever > 38 °C; 3) Vascular/immunological signs; 4) Positive blood culture, not fulfilling major criteria; 5) Positive echocardiogram, not fulfilling major criteria.

ECG findings may be normal or may depict long PR interval. TOE is superior to trans-thoracic echocardiography in demonstration of dangling intra-cavitary vegetations or abscess formation [8]. Raised inflammatory markers and deranged LFTs can be found. Hematuria may also be present. Culture of blood and surgically removed vegetations may fail to reveal causative organism in 2.5 to 31% of cases. In such cases PCR amplification and direct sequencing of the colonized bacteria from the excised vegetations on the affected valve leaflets has been on trials and is said to be superior in isolating the organism, however is still in evolving phase and may not be available on blood samples yet [9].

These vegetations provide deep habitat to bacteria and are devoid of white cells thus making them less responsive to antibiotics, necessitating longer treatment duration of about 4 - 6 weeks [10].

In many cases where either patient fails to respond to medical treatment, manifests infectious embolism, has increasing heart failure, where vegetations are too many to eradicate or in cases where metallic valve is the vegetations’ bed, surgical removal and valve replacement is needed to cure the patient [11].

The surgical treatment includes excision of the affected valve with or without removal of the annulus fibrosus during open heart surgery. If mechanical device is the cause, removal with subsequent replacement is the only option.

Prophylactic antibiotics have been discontinued recently as the prevention guidelines have not been proven to be superior to patients without prophylaxis [12]. Mortality rate varies from 6% to 30% depending on the involved organism [13].

Our cases were unique because all patients presented with high grade fever and had positive blood cultures showing different organisms. Trans-thoracic echocardiography was negative while TOE revealed features of infective endocarditis. One of the patients had secondary infective pulmonary emboli. They were successfully treated with antibiotics and enhanced follow-up. In conclusion, infective endocarditis may have severe complications; therefore, prompt clinical suspicion, early diagnosis and appropriate medical/surgical intervention should be carried out to limit the associated morbidity and mortality. TOE has shown excellent results in the early diagnosis and follow-up.

| References | ▴Top |

- Millar BC, Moore JE. Emerging issues in infective endocarditis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(6):1110-1116.

pubmed - Ferreiros E, Nacinovich F, Casabe JH, Modenesi JC, Swieszkowski S, Cortes C, Hernan CA,

et al . Epidemiologic, clinical, and microbiologic profile of infective endocarditis in Argentina: a national survey. The Endocarditis Infecciosa en la Republica Argentina-2 (EIRA-2) Study. Am Heart J. 2006;151(2):545-552.

doi pubmed - Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, Fowler VG

Jr , Bolger AF, Levison ME, Ferrieri P,et al . Infective endocarditis: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association: endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Circulation. 2005;111(23):e394-434.

doi pubmed - Tembe AG, Kharbanda P, Dalal JJ, Vaishnav G, Joshi VR. Infective endocarditis—a tale of two cases and the lessons (re)learned. J Assoc Physicians India. 2010;58:319-322.

pubmed - Brouqui P, Raoult D. Endocarditis due to rare and fastidious bacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14(1):177-207.

doi pubmed - Beynon RP, Bahl VK, Prendergast BD. Infective endocarditis. BMJ. 2006;333(7563):334-339.

doi pubmed - Hoen B, Beguinot I, Rabaud C, Jaussaud R, Selton-Suty C, May T, Canton P. The Duke criteria for diagnosing infective endocarditis are specific: analysis of 100 patients with acute fever or fever of unknown origin. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23(2):298-302.

doi pubmed - Tornos P, Gonzalez-Alujas T, Thuny F, Habib G. Infective endocarditis: the European viewpoint. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2011;36(5):175-222.

doi pubmed - Podglajen I, Bellery F, Poyart C, Coudol P, Buu-Hoi A, Bruneval P, Mainardi JL. Comparative molecular and microbiologic diagnosis of bacterial endocarditis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9(12):1543-1547.

pubmed - Shun CT, Yeh CY, Chang CJ, Wu SH, Lien HT, Chen JY, Wang SS,

et al . Activation of human valve interstitial cells by a viridians streptococci modulin induces chemotaxis of mononuclear cells. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(10):1488-1496.

doi pubmed - Prendergast BD, Tornos P. Surgery for infective endocarditis: who and when?. Circulation. 2010;121(9):1141-1152.

doi pubmed - Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, Lockhart PB, Baddour LM, Levison M, Bolger A,

et al . Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(Suppl):3S-24S.

doi pubmed - Wallace SM, Walton BI, Kharbanda RK, Hardy R, Wilson AP, Swanton RH. Mortality from infective endocarditis: clinical predictors of outcome. Heart. 2002;88(1):53-60.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.