| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 5, Number 3, March 2014, pages 125-128

A Carotid Body Tumor Mimicking a Thyroid Nodule

Husniye Basera, e, Baris Ayhanb, Meryem Ilkay Eren Karanisc, Salih Baserd, Deniz Karasoyd, Kemal Kalkand, Samil Ecirlid

aDepartment of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Konya Education and Research Hospital, Konya, Turkey

bDepartment of General Surgery, Konya Education and Research Hospital, Konya, Turkey

cDepartment of Pathology, Konya Education and Research Hospital, Konya, Turkey

dDepartment of Internal Medicine, Konya Education and Research Hospital, Konya, Turkey

eCorresponding author: Husniye Baser, Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Konya Education and Research Hospital, Meram, Konya, Turkey

Manuscript accepted for publication January 20, 2014

Short title: Carotid Body Tumor

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc1966e

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Paragangliomas (PGLs) are neuroendocrine tumors arising from the extra-adrenal chromaffin tissue of the autonomic nervous system. They are most frequently found in the head and neck, mainly associated with the carotid body, vagus nerve, jugulotympanic paraganglia, and occasionaly, the superior-inferior paraganglia. Paragangliomas are rarely encountered in thyroid as well, and thyroid paragangliomas can be misinterpreted as medullary thyroid carcinomas. However, cases of paragangliomas mimicking thyroid nodules were also reported in literature rarely. In this article, we reported a case first giving an impression of a thyroid nodule, then suggesting the likelihood of a medullary thyroid carcinoma or intrathyroidal paraganglioma via core needle biopsy, but finally was diagnosed as a carotid body tumor.

Keywords: Paraganglioma; Carotid body tumor; Thyroid nodule

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Paragangliomas (PGLs) are uncommon tumors, incidence rate is 1 to 2 per 100,000, and the tumors are often given special designations, depending on their locations [1]. Only 3% of all PGLs occur within head and neck, the majority of which are located in carotid body (carotid body tumors), temporal-bone/middle-ear (glomus jugulare) and vagus nerve in neck (vagal PGLs) [2, 3]. Ninety percent of head and neck PGLs are sporadic, while only 10% are hereditary in nature [2]. In literature, cases of PGL mimicking thyroid nodules are rarely encountered [4, 5]. In the report, we will present a case of PGL (a carotid body tumor) that we initially evaluated as a thyroid nodule, and then diagnosed as a PGL.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

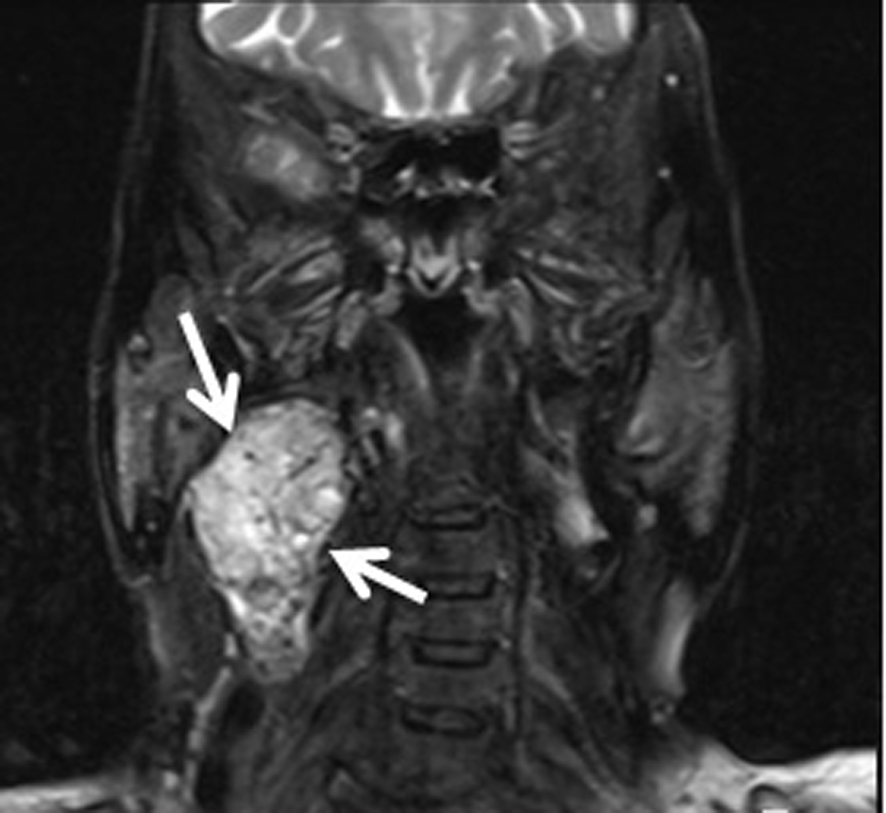

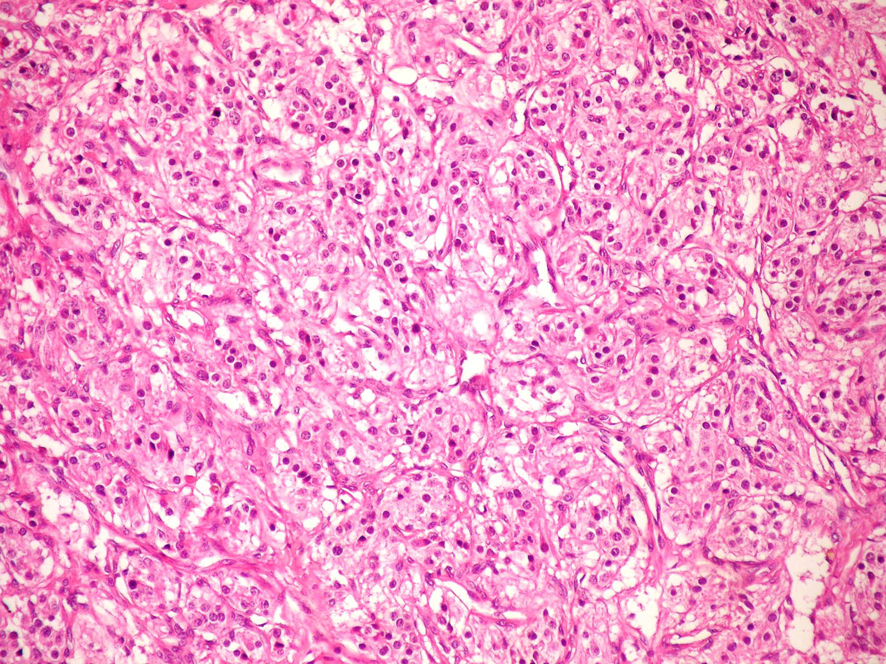

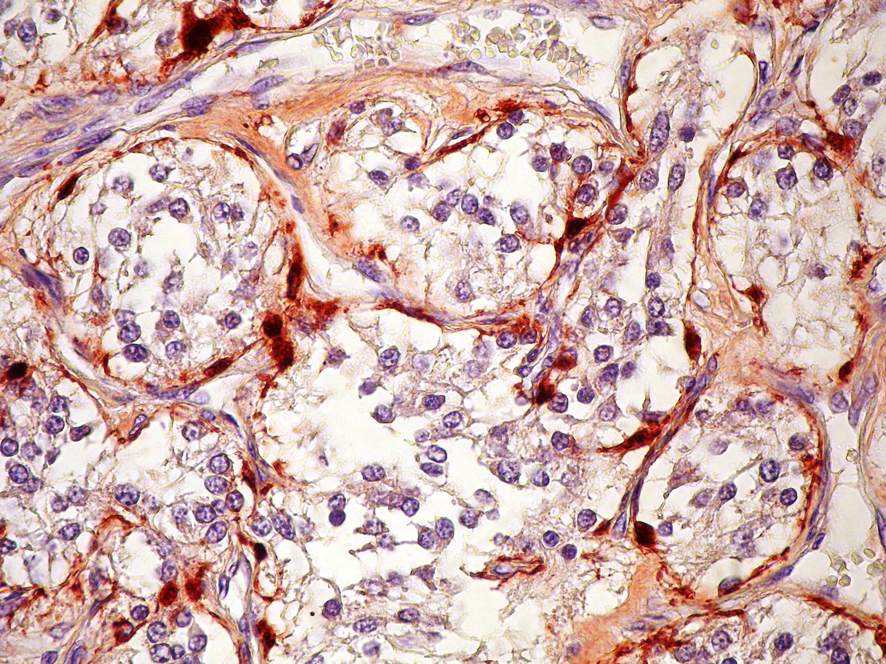

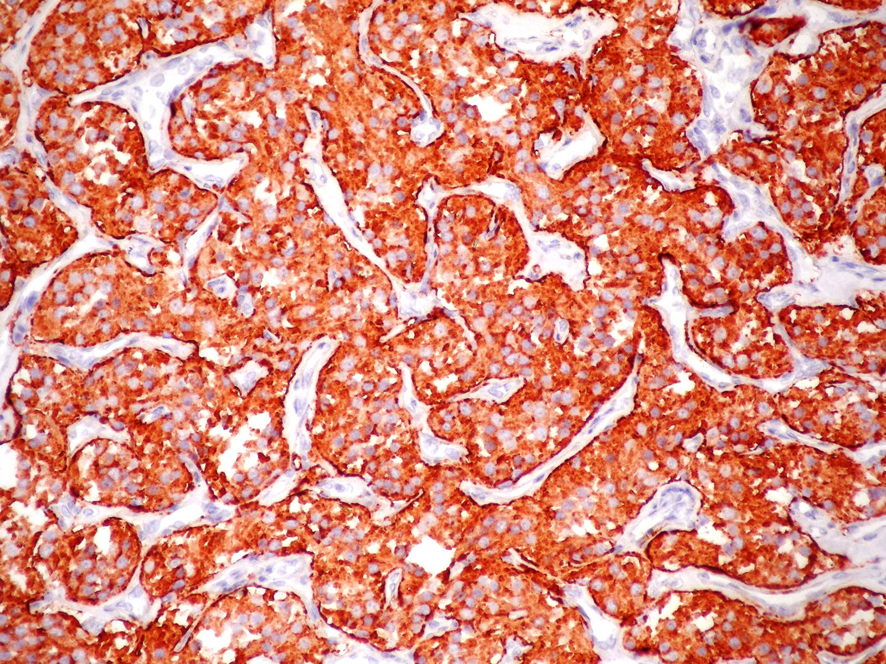

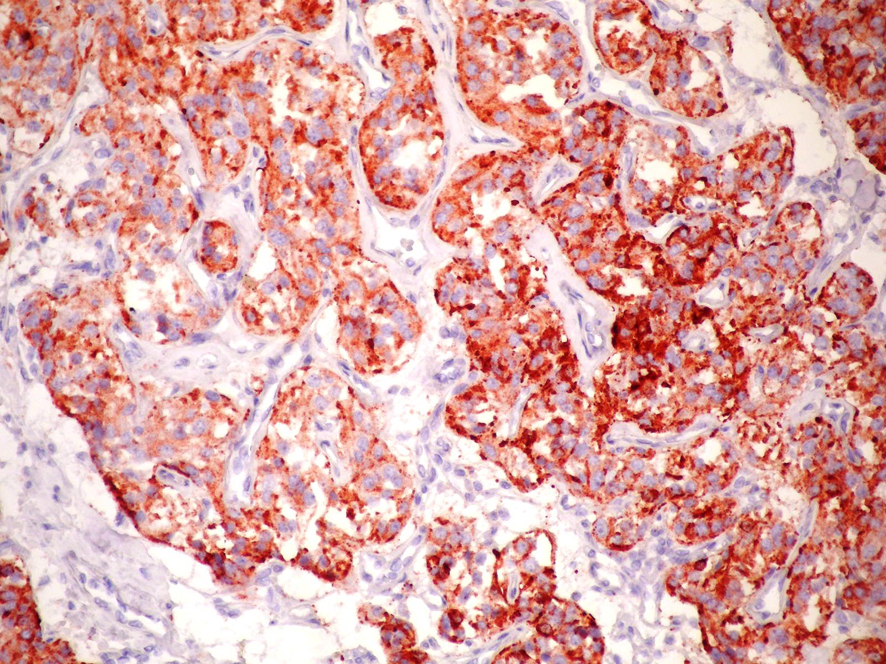

A 74-year-old woman was admitted due to a mass in the right side of neck growing rapidly within the last 1 month. The case reported no complaints of dysphagia or dysphonia. The family history of the case revealed no carcinoma and thyroid disease. While no history of flushing, hypertensive attacks, diarrhea, and other symptoms related to catecholamines hypersecretion was detected, hypertension was present in her personal medical history. She was lack of the history of neck irradiation. Physical examination revealed a hard and painless mass with smooth surface, extending from right thyroid lobe level to angulus mandibula and measuring 8 cm without palpable cervical lymph nodes. Indirect laryngoscopy showed normal mobile vocal cords. Thyroid stimulating hormone, free triiodothyronine and free tetraiodothyronine were within normal ranges, and anti-peroxidase and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies were found to be negative. Ultrasound (US) examination showed two hypoechoic and non-homogeneous nodules deplaced the trachea to left in the right thyroid lobe, one in size of 46 х 37 mm and the other in size of 44 х 38 mm, and a isoechoic nodule in size of 23 х 15 mm in the left thyroid lobe. For 3 nodules, a US-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) was performed, and the nodules were reported to be benign. On neck magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 1), a mass of 7 х 5.5 cm with intense pathologic contrast, extending from right thyroid lobe level to angulus mandibula, and deplaced larynx and trachea to left was observed. Because of the existence of rapidly growing thyroid nodules in the case, core needle biopsy was performed for the nodules in right thyroid lobe due to suspected thyroid malignancy, and histopathologic findings were found to be consistent with neuroendocrine tumor. Immunohistochemical examination revealed that synaptophisin and chromogranin A were positive, but calcitonin, thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) and thyroglobulin (Tg) were negative. The level of serum calcitonin was 2.8 pg/mL (normal range 0-11.5 pg/mL), fractionated urinary catecholamine levels were normal, and on positron emission tomography (PET)-computerized tomography (CT), increased 2-[fluorine-18]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) involvement was observed in thyroid (SUVmax 7.8) and right paratracheal, aortopulmonary, subcarinal and bilateral hilar regions (SUVmax 15.5). The excision of mediastinal lympnodes and bilateral total thyroidectomy were performed. During the surgery, a mass of 4 х 3 cm was seen in the right carotid artery bifurcation and excised. Macroscopically, the mass was encapsulated, yellowish-white and soft. Microscopically, the tumor cells were arranged in well-defined nests (Zellballen) and encircled by a thin layer of S-100 protein and GFAP positive, spindle-shaped sustentacular cells (Fig 2, 3). Tumor cells vary in size and shape, and have a finely granular cytoplasm. The nuclei were round to oval with coarsely granular chromatin with a so-called salt-and-pepper appearance. No definite pleomorphism, necrosis or mitosis was witnessed. In tumor cells, immunohistochemical CD56, synaptophisin (Fig. 4), neuron specific enolase (NSE) and chromogranin A (Fig. 5) were positive, but calcitonin, TTF-1 and Tg were negative. The proliferation index of Ki-67 was lower than 1%. In light of these findings, the case was diagnosed with PGL, and the histopathologic findings of other thyroid nodules were consistent with colloidal nodules. In addition, the histopathology of mediastinal lymph nodes was evaluated as reactive hyperplasia.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Neck magnetic resonance imaging of the case. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Microscopic photograph of paraganglioma, HE × 200. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Immunstain for S-100 protein shows positive staining in sustentacular cells, S-100 × 400. |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Immunstain for Synaptophysin shows positive staining in tumor cells, Synaptophysin × 200. |

Click for large image | Figure 5. Immunstain for chromogranin A shows positive staining in tumor cells, Chromogranin A × 200. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

PGLs are rare tumors derived from extra-adrenal paraganglionic system, which consist of cells from the neural crest associated with autonomous nervous system [6, 7]. PGLs are seen at many sites in head and neck areas, including carotid body, jugular-tympanic region and vagus nerve [7, 8]. Unlike pheochromocytomas, PGLs in head and neck regions are usually non-functioning tumors.

The classic radiographic features are homogeneous or heterogeneous hyper-enhancing soft-tissue mass as shown by CT scan, multiple areas of signal void interspersed with hyperintense foci (salt-and-pepper appearance) within a tumor mass as shown by MRI, and as an intense tumor blush with enlarged feeding arteries by angiography [9].

Histopathologically, PGLs have a characteristic growth pattern often referred to as a “zellballen” growth pattern. Tumor cells are predominantly chief cells with round, hyperchromatic nuclei, a dispersed chromatin and abundant granular cytoplasm ranging from eosinophilic to basophilic in color. Neuromelanin pigment may occasionally be seen, and amyloid deposition has also been described in PGLs. Like the pheochromocytes of adrenal pheochromocytomas, tumor cells demonstrate reactivity to chromogranin and synaptophisin stains by immunohistochemical techniques, as well as other markers of neuroendocrine differentiation such as CD56 and NSE. The population of sustentacular cells can usually be identified at the periphery of nests and are thought to be modified Schwann cells and to be spindle-shaped, and can be highlighted with S-100 protein staining.

Among the disorders most easily mistaken for cervical PGLs, particularly those arising within larynx or thyroid, are neuroendocrine carcinomas, such as atypical carcinoids and medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) [10-15]. Another disorder that may be confused with PGLs is hyalinizing trabecular adenoma, a benign thyroid neoplasm showing a prominent nesting pattern resembling a PGL [14, 16, 17]. This rare entity is usually negative for chromogranin and positive for Tg and cytokeratins.

In literature, PGLs are generally reported as slowly growing neck masses without pain [7, 18]. Rarely, they may attain large size and infiltrative growth, and the local recurrence of PGLs may lead to death. Our case was admitted due to a mass growing rapidly in the neck region, and multinodular guatr was determined on US imaging. Although the first FNAB was benign, we performed core needle biopsy due to the suspicion of thyroid malignancy. The fact that the core needle biopsy was consistent with neuroendocrine tumor suggested the likelihood of MTC or an intrathyroidal PGL. The case exhibited a normal level of serum calcitonin, and the negativity of staining with calcitonin decreased MTC likelihood. However, the positivity of synaptophisin and chromogranin A in immunohistochemical staining, and normal levels of urinary catecholamine were evaluated in favor of a non-functional intrathyroidal PGL. Even so, interpreted first as a thyroid nodule on US imaging, a carotid body tumor was observed in the right carotid artery bifurcation during the operation; on the other hand, thyroid histopathology was benign.

FNAB can be performed on numerous occasions to establish a diagnosis of PGLs [19-24]. However, the exact role of FNAB in the diagnosis of these tumors currently remains controversial. The main concern in performing a pre-operative FNAB on suspected PGLs is the risk of hemorrhage and hematoma [22, 24]. In our case, carotid body tumor suggested the impression of a thyroid nodule, so FNAB was performed, but no complication was seen as a result of biopsy.

Malignancy cannot be determined by cytology or even by histologic findings and can only be defined when the tumor metastasizes to regional lymph nodes or more distant sites. Nuclear pleomorphism, neurovascular invasion, high mitotic index and necrosis have been described in both benign and malignant types of tumors [2]. In literature, the ratio of proven cervical malignant PGLs is low ranging from 2 to 10% for carotid and vagal body tumors and is less than 2% for laryngeal PGLs [11, 12]. In our case, the determination of mediastinal lymphadenopathies on PET-CT suggested the likelihood of a malignant PGL; however, no malignancy was encountered in the histopathology of mediastinal lymph nodes.

In conclusion, cervical PGLs are uncommon tumors, so healthcare providers should take the likelihood of PGLs into account in the differential diagnosis of neck masses.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

| References | ▴Top |

- Sevilla Garcia MA, Llorente Pendas JL, Rodrigo Tapia JP, Garcia Rostan G, Suarez Fente V, Coca Pelaz A, Suarez Nieto C. [Head and neck paragangliomas: revision of 89 cases in 73 patients]. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2007;58(3):94-100.

doi - Barnes L, Tse LL, Hunt JL, Michaels L. Tumors of paraganglionic system: Introduction. In: Barnes L, Eveson J, Reichart P, Sidranskey D, editors. WHO Clasification of Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. pp. 361-370.

- Choussy O, Babin E, De Barros A, Bon-Mardion N, Marie JP, Dehesdin D. Vagal paraganglioma of the neck: a case report. Ear Nose Throat J. 2009;88(12):E1-3.

pubmed - Pinto FR, Capelli Fde A, Maeda SA, Pereira EM, Scarpa MB, Brandao LG. Unusual location of a cervical paraganglioma between the thyroid gland and the common carotid artery: case report. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2008;63(6):845-848.

doi - Kieu V, Yuen A, Tassone P, Hobbs CG. Cervical paraganglioma presenting as thyroid neoplasia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146(3):516-518.

doi pubmed - Tischler AS, Kimura N, McNicol AM. Pathology of pheochromocytoma and extra-adrenal paraganglioma. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1073:557-570.

doi pubmed - Paris J, Facon F, Thomassin JM, Zanaret M. Cervical paragangliomas: neurovascular surgical risk and therapeutic management. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263(9):860-865.

doi pubmed - Martinez-Madrigal F, Bosq J, Micheau C, Nivet P, Luboinski B. Paragangliomas of the head and neck. Immunohistochemical analysis of 16 cases in comparison with neuro-endocrine carcinomas. Pathol Res Pract. 1991;187(7):814-823.

doi - Lee KY, Oh YW, Noh HJ, Lee YJ, Yong HS, Kang EY, Kim KA,

et al . Extraadrenal paragangliomas of the body: imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187(2):492-504.

doi pubmed - Barnes L. Paraganglioma of the larynx. A critical review of the literature. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1991;53(4):220-234.

doi pubmed - Ferlito A, Barnes L, Wenig BM. Identification, classification, treatment, and prognosis of laryngeal paraganglioma. Review of the literature and eight new cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1994;103(7):525-536.

pubmed - Hinojar AG, Prieto JR, Munoz E, Hinojar AA. Relapsing paraganglioma of the inferior laryngeal paraganglion: case report and review of the literature. Head Neck. 2002;24(1):95-102.

doi pubmed - de Vries EJ, Watson CG. Paraganglioma of the thyroid. Head Neck. 1989;11(5):462-465.

doi - Corrado S, Montanini V, De Gaetani C, Borghi F, Papi G. Primary paraganglioma of the thyroid gland. J Endocrinol Invest. 2004;27(8):788-792.

pubmed - Yano Y, Nagahama M, Sugino K, Ito K, Kameyama K. Paraganglioma of the thyroid: report of a male case with ultrasonographic imagings, cytologic, histologic, and immunohistochemical features. Thyroid. 2007;17(6):575-578.

doi pubmed - Hughes JH, El-Mofty S, Sessions D, Liapis H. Primary intrathyroidal paraganglioma with metachronous carotid body tumor: report of a case and review of the literature. Pathol Res Pract. 1997;193(11-12):791-796, discussion 797-799.

doi - Bizollon MH, Darreye G, Berger N. [Thyroid paraganglioma: report of a case]. Ann Pathol. 1997;17(6):416-418.

pubmed - Plouin PF, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. Initial work-up and long-term follow-up in patients with phaeochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;20(3):421-434.

doi pubmed - Varma K, Jain S, Mandal S. Cytomorphologic spectrum in paraganglioma. Acta Cytol. 2008;52(5):549-556.

doi pubmed - Schreiner AM, Fried K, Yang GC. Interconnecting cytoplasmic processes on fine-needle aspiration smears of carotid body paraganglioma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38(7):507-508.

doi pubmed - Gong Y, DeFrias DV, Nayar R. Pitfalls in fine needle aspiration cytology of extraadrenal paraganglioma. A report of 2 cases. Acta Cytol. 2003;47(6):1082-1086.

doi pubmed - Rosa M, Sahoo S. Bilateral carotid body tumor: the role of fine-needle aspiration biopsy in the preoperative diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36(3):178-180.

doi pubmed - Mondal P, Basu N, Gupta SS, Bhattacharya N, Mallick MG. Fine needle aspiration cytology of parapharyngeal tumors. J Cytol. 2009;26(3):102-104.

doi pubmed - Chiu GA, Edwards AI, Akhtar S, Hill JC, Hanson IM. Carotid body paraganglioma manifesting as a malignant solitary mass on imaging: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109(4):e54-58.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.