| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 5, Number 6, June 2014, pages 376-379

Treatment of Cholesterol Embolization Syndrome in the Setting of an Acute Indication for Anticoagulation Therapy

Hidong Kima, David B. Zhena, John C. Lieskeb, Robert D. McBanec, Joseph P. Granded, Gurpreet S. Sandhuc, Rowlens M. Meldunic, e

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA

bDivision of Nephrology and Hypertension, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA

cDivision of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA

dDivision of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA

eCorresponding Author: Rowlens M. Melduni, Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic, 200 First St SW, Rochester, MN 55905, USA

Manuscript accepted for publication May 15, 2014

Short title: Treatment of Cholesterol Embolization Syndrome

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc1804w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Cholesterol embolization syndrome (CES) is a complication sometimes occurring after invasive endovascular procedures. CES is characterized by release of cholesterol crystals and particles from atheromatous plaques, which can occlude distal vessels and induce an inflammatory response, resulting in end-organ damage. We report the case of a 66-year-old man who presented with an acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction. An intra-aortic balloon pump was placed due to hemodynamic instability following percutaneous coronary intervention. Ten weeks after discharge, he presented with signs and symptoms of CES (e.g., livedo reticularis, acrocyanosis, acute renal failure), and a new left ventricular apical thrombus. Withdrawal of anticoagulation is often recommended in the setting of CES, on the presumption that anticoagulants favor plaque hemorrhage and subsequent cholesterol micro-embolization. Because of the potential disastrous consequences of an embolus, the patient was anticoagulated with warfarin concurrently with corticosteroids to suppress the inflammatory response to cholesterol crystals. His renal function continued to improve and he was discharged without the need for dialysis. This case illustrates that anticoagulation therapy in CES is feasible and appears to be safe in patients with a coexisting urgent indication for anticoagulation.

Keywords: Acrocyanosis; Atheroemboli; Livedo reticularis; Blue toe syndrome; Cholesterol embolization; Vascular ischemia; Cholesterol crystal

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Cholesterol embolization syndrome (CES) is characterized by release of cholesterol crystals and particles from atheromatous plaques. These emboli can occlude distal vessels and induce an inflammatory response, resulting in end-organ damage, including infarction [1-3]. Embolization of these crystals and particles may occur spontaneously or, more commonly, may be triggered by invasive endovascular procedures [4-6]. Cholesterol emboli (aka atheroemboli) are generally smaller than thromboemboli and are more likely to occlude smaller arteries and arterioles with lumen diameter of 150 - 200 µm [7]. Acute kidney injury is a common manifestation of CES and is seen in 25-50% of cases [8, 9]. Ischemic skin changes, including blue toe syndrome, are seen in about one-third of cases [9]. Treatment of CES is largely supportive [10]. Limited evidence suggests that anti-inflammatory therapy, including corticosteroids or prostacyclin analogues, or both, may be beneficial in selected cases [11, 12]. If the embolic event occurs in actively anti-coagulated patients (e.g., heparin, warfarin), these medications are generally withdrawn based on the presumption that plaque hemorrhage with subsequent cholesterol micro-embolization is the culprit mechanism [13]. Herein, we describe the complex treatment of a man with CES following invasive arterial interventions after an acute myocardial infarction (MI). Medical management was complicated by a concurrent, new left ventricular (LV) apical thrombus.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 66-year-old man presented to his local emergency department (ED) with chest pain, and was diagnosed with an acute non-ST elevation MI. He was initiated on IV heparin and dual anti-platelet therapy and transferred to Mayo Clinic Hospital for further management. On arrival, his ECG showed mild ST elevation in the anterolateral leads. Coronary angiography showed severe multi-vessel coronary artery disease. Echocardiography showed severely reduced LV systolic function, an ejection fraction of 22%, and akinesis of the anterior and anterolateral walls and apex. The patient subsequently developed recurrent chest pain with pronounced ST-segment elevation in the anterolateral leads. An intra-aortic balloon pump was placed followed by CABG surgery.

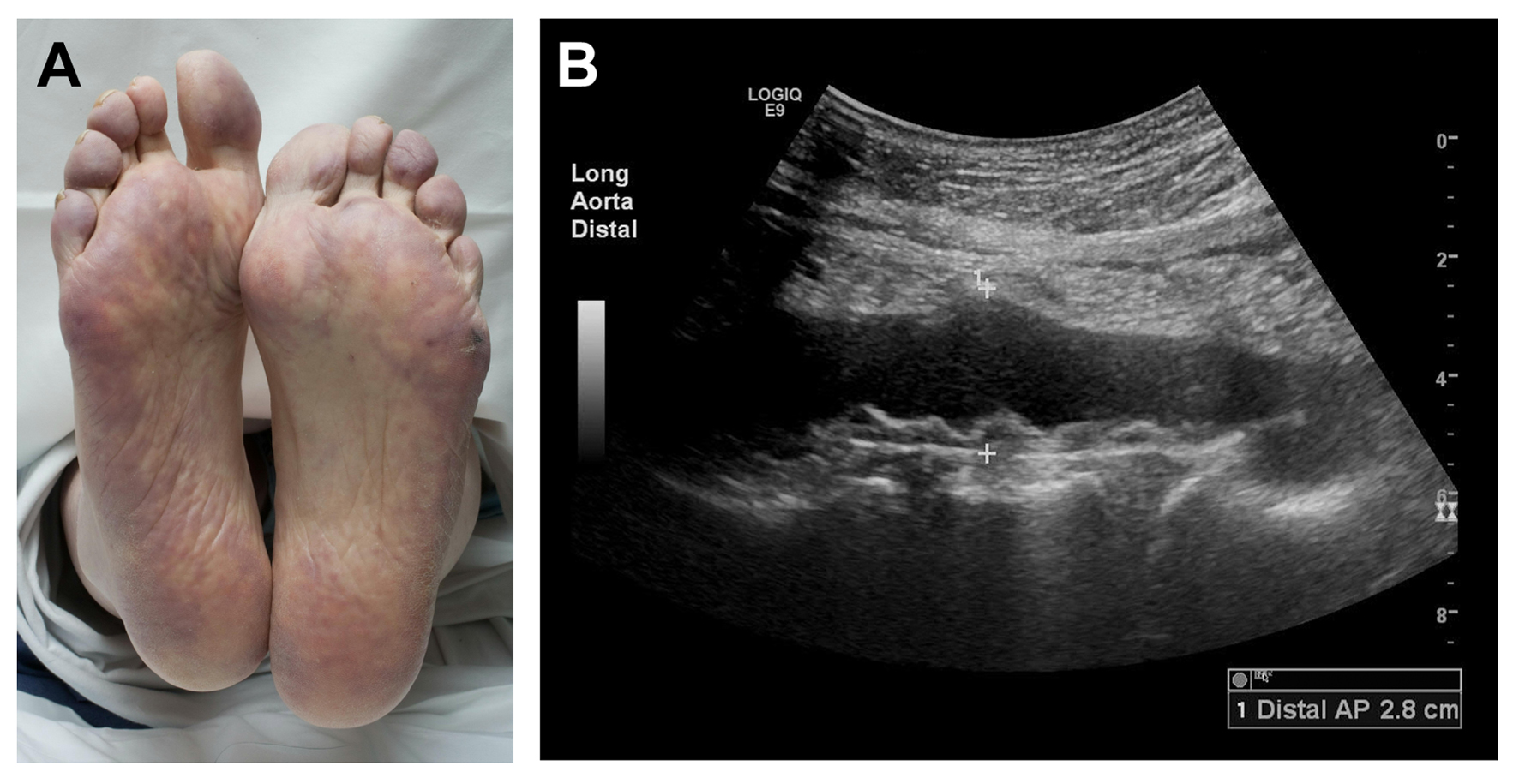

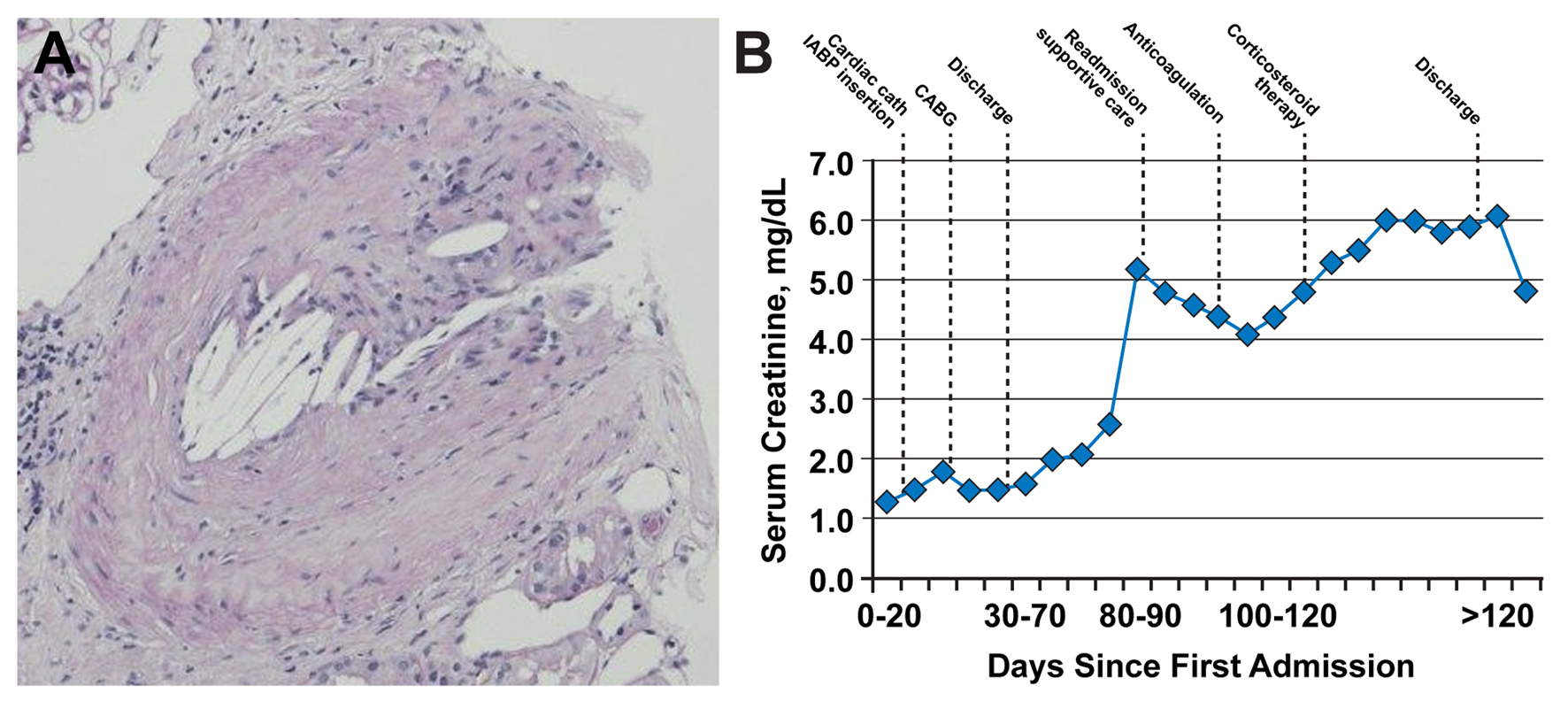

Following hospital dismissal, his creatinine was noted to progressively rise from a baseline of 1.3 mg/dL to 2.0 mg/dL one week post-discharge, to 5.2 mg/dL 10 weeks later. His eosinophil count was also elevated. A follow-up echocardiogram revealed a new LV apical thrombus. Because of his deteriorating clinical status, he was readmitted to the hospital. His physical examination was notable for livedo reticularis on the plantar surfaces and acrocyanosis bilaterally (Fig. 1A). Renal ultrasound showed no hydronephrosis or localized wedge-shaped lesions. These findings, following recent endovascular interventions, raised clinical suspicion for CES. Ultrasound of the aorta showed mobile atheromatous plaques in the abdominal aorta (Fig. 1B). Renal biopsy showed morphologic alterations within arteries and arterioles consistent with atheroembolic renal disease (Fig. 2A).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Ischemic skin manifestations of cholesterol embolization syndrome. (A) Marked purplish discoloration of plantar surfaces (livedo reticularis) and pallor and cyanosis of the toes, indicating acute loss of perfusion, several weeks after percutaneous intra-arterial intervention in a patient with (B) severe atherosclerosis of the thoracoabdominal aorta. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Renal biopsy results. (A) Occlusion of a branch renal artery by cholesterol emboli (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification, × 100). Evidence of dissolved cholesterol crystals is represented by needle-shaped cholesterol clefts. (B) Time course of serum creatinine values in the days following initial vascular insult. Graph shows initial steady increase of serum creatinine and initial improvement with supportive care (mainly, intravenous fluid hydration), followed by worsening after initiation of anticoagulation, with subsequent stabilization and improvement after initiation of corticosteroid therapy. CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; cath: catheterization; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump. |

The patient’s creatinine level initially decreased from 5.2 mg/dL on readmission to 4.1 mg/dL on day 4 (Fig. 2B). Serum creatinine then resumed an upward trend as the INR increased to the therapeutic range. Corticosteroid therapy was initiated to suppress the inflammatory response to the cholesterol crystals. Subsequently, the serum creatinine level stabilized in the range of 5.8 - 6.0 mg/dL, followed by a slow decline. He was discharged in stable condition on day 12 with a creatinine level of 5.9 mg/dL. The patient’s last serum creatinine level was 4.8 mg/dL at 2 weeks after discharge.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Cholesterol crystal embolization is a rare, but serious, complication of invasive endovascular procedures in patients with advanced atherosclerosis. The incidence of clinically apparent cholesterol embolization after such procedures ranges from less than 1% after cardiac surgery [8] to 1.4% after cardiac catheterization [4, 14], but it has been noted in up to 30% of similar cases in autopsy series [7]. Other risk factors for cholesterol embolization include hypertension and thrombolytic therapy [9]. Possible effects of the emboli include neurologic injury [1], gastrointestinal infarcts, renal failure and ischemic skin changes. End-organ manifestations generally correlate with blood flow distribution distal to the source. Hence, renal failure is commonly observed in association with CES since the kidneys receive 20-25% of cardiac output [3, 5, 16].

Other possible manifestations include fever, eosinophilia and elevated levels of inflammatory markers, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. Up to 80% of CES cases may show eosinophilia [15]. Although eosinophiluria may be seen, its diagnostic accuracy for identifying atheroembolic renal disease is limited and varies depending on the stain used [17]. Therefore, the presence of urine eosinophils should be interpreted in the context of other clinical clues. Definitive diagnosis is made by renal biopsy. In the present case, progressive renal failure, ischemic skin changes and eosinophilia in the situation of recent invasive endovascular procedures raised the clinical suspicion of CES, which was subsequently confirmed by renal biopsy.

Treatment of CES is largely supportive [10] and generally consists of fluid and blood pressure support, hemodialysis when indicated, and nutritional and metabolic support. Surgical removal of the embolic source is warranted for those cases occurring spontaneously to prevent recurrent embolic showers. The role of anticoagulation therapy in CES remains controversial. Although no randomized trials have specifically evaluated anticoagulation as a potential CES risk factor, previous studies have suggested an association between anticoagulation and plaque hemorrhage, plaque rupture and subsequent cholesterol crystal embolization [13, 18, 19]. In the absence of prior endovascular procedures, anticoagulation alone is temporally associated with approximately 7% of CES renal disease cases [20]. Thus, treatment of CES generally entails withdrawal or avoidance of anticoagulation [10].

In the present case, CES management was complicated by the acute indication for anticoagulation (LV thrombus). Because potential consequences of an embolus can be disastrous, withdrawal of anticoagulation in such cases requires careful consideration of potential risks and benefits. In the absence of anticoagulation, the risk of embolization in patients with LV thrombus, particularly if mobile or protruding, as in our patient, has been reported to be between 10% and 15%, with most events occurring within the first few weeks after acute MI [21, 22]. Prior studies have suggested that early anticoagulation lowers the risk of thrombus embolization [23, 24]. Current consensus is to continue anticoagulation in patients with a concurrent indication for it (e.g., mechanical prosthetic valve, new intravascular thrombus, atrial fibrillation) [25].

Conclusion

Cholesterol embolism is a rare, but serious complication of invasive endovascular procedures. It may result in ischemic end-organ damage from distal embolization of ruptured plaque in the aorta. Early recognition demands a high index of suspicion based on clinical findings of ischemic skin lesions, gradual-onset renal failure, elevated levels of inflammatory markers and eosinophilia. Treatment is generally supportive. Although no definitive treatment is established for CES, use of anticoagulant therapy in cholesterol embolization appears to be feasible and safe in patients with a coexisting urgent indication for anticoagulation.

Conflict of Interest

None.

| References | ▴Top |

- Ezzeddine MA, Primavera JM, Rosand J, Hedley-Whyte ET, Rordorf G. Clinical characteristics of pathologically proved cholesterol emboli to the brain. Neurology. 2000;54(8):1681-1683.

doi pubmed - Gore I, McCombs HL, Lindquist RL. Observations on the Fate of Cholesterol Emboli. J Atheroscler Res. 1964;4:527-535.

doi - Scolari F, Tardanico R, Zani R, Pola A, Viola BF, Movilli E, Maiorca R. Cholesterol crystal embolism: A recognizable cause of renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36(6):1089-1109.

doi pubmed - Drost H, Buis B, Haan D, Hillers JA. Cholesterol embolism as a complication of left heart catheterisation. Report of seven cases. Br Heart J. 1984;52(3):339-342.

doi pubmed - Karalis DG, Quinn V, Victor MF, Ross JJ, Polansky M, Spratt KA, Chandrasekaran K. Risk of catheter-related emboli in patients with atherosclerotic debris in the thoracic aorta. Am Heart J. 1996;131(6):1149-1155.

doi - Ramirez G, O'Neill WM

Jr , Lambert R, Bloomer HA. Cholesterol embolization: a complication of angiography. Arch Intern Med. 1978;138(9):1430-1432.

doi pubmed - Fries C, Roos M, Gaspert A, Vogt P, Salomon F, Wuthrich RP, Vavricka SR,

et al . Atheroembolic disease—a frequently missed diagnosis: results of a 12-year matched-pair autopsy study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2010;89(2):126-132.

doi pubmed - Doty JR, Wilentz RE, Salazar JD, Hruban RH, Cameron DE. Atheroembolism in cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75(4):1221-1226.

doi - Fine MJ, Kapoor W, Falanga V. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a review of 221 cases in the English literature. Angiology. 1987;38(10):769-784.

doi pubmed - Belenfant X, Meyrier A, Jacquot C. Supportive treatment improves survival in multivisceral cholesterol crystal embolism. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;33(5):840-850.

doi - Elinav E, Chajek-Shaul T, Stern M. Improvement in cholesterol emboli syndrome after iloprost therapy. BMJ. 2002;324(7332):268-269.

doi pubmed - Mann SJ, Sos TA. Treatment of atheroembolization with corticosteroids. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14(8 Pt 1):831-834.

doi - Hyman BT, Landas SK, Ashman RF, Schelper RL, Robinson RA. Warfarin-related purple toes syndrome and cholesterol microembolization. Am J Med. 1987;82(6):1233-1237.

doi - Fukumoto Y, Tsutsui H, Tsuchihashi M, Masumoto A, Takeshita A, Cholesterol Embolism Study I. The incidence and risk factors of cholesterol embolization syndrome, a complication of cardiac catheterization: a prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(2):211-216.

doi - Kasinath BS, Corwin HL, Bidani AK, Korbet SM, Schwartz MM, Lewis EJ. Eosinophilia in the diagnosis of atheroembolic renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 1987;7(3):173-177.

doi pubmed - Thadhani RI, Camargo CA

Jr , Xavier RJ, Fang LS, Bazari H. Atheroembolic renal failure after invasive procedures. Natural history based on 52 histologically proven cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995;74(6):350-358.

doi - Wilson DM, Salazer TL, Farkouh ME. Eosinophiluria in atheroembolic renal disease. Am J Med. 1991;91(2):186-189.

doi - Bruns FJ, Segel DP, Adler S. Control of cholesterol embolization by discontinuation of anticoagulant therapy. Am J Med Sci. 1978;275(1):105-108.

doi pubmed - Talmadge DB, Spyropoulos AC. Purple toes syndrome associated with warfarin therapy in a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(5):674-677.

doi - Sharma PV, Babu SC, Shah PM, Nassoura ZE. Changing patterns of atheroembolism. Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;4(5):573-579.

doi - Stratton JR, Resnick AD. Increased embolic risk in patients with left ventricular thrombi. Circulation. 1987;75(5):1004-1011.

doi - Visser CA, Kan G, Meltzer RS, Dunning AJ, Roelandt J. Embolic potential of left ventricular thrombus after myocardial infarction: a two-dimensional echocardiographic study of 119 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;5(6):1276-1280.

doi - Reeder GS, Lengyel M, Tajik AJ, Seward JB, Smith HC, Danielson GK. Mural thrombus in left ventricular aneurysm: incidence, role of angiography, and relation between anticoagulation and embolization. Mayo Clin Proc. 1981;56(2):77-81.

pubmed - Vaitkus PT, Barnathan ES. Embolic potential, prevention and management of mural thrombus complicating anterior myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22(4):1004-1009.

doi - Quinones A, Saric M. The cholesterol emboli syndrome in atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15(4):315.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.