| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 5, Number 8, August 2014, pages 449-451

Fatal Strongyloides Hyperinfection in Post-Deceased Kidney Transplant Presented With Respiratory Failure and Septic Shock

Rasheed Jaffar Al-Hubaila, Adel Hammodi Alia, Ahmed Hanafy Alia, Naglaa Hassan Mahmouda, b

aKing Fahad Specialist Hospital, Dammam, Saudi Arabia

bCorresponding Author: Naglaa Hassan Mahmoud, King Fahad Specialist Hospital, Dammam, Saudi Arabia

Manuscript accepted for publication July 4, 2014

Short title: Strongyloides Hyperinfection

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc1848w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Immunocompromised patients are a vulnerable group to develop opportunistic infections. Transplant patients are always immunocompromised either because of their illness or immune-modulatory drugs that they receive. Strongyloidiasis is one of the opportunistic infections that increasingly attack transplant patients. We report this case of strongyloides hyperinfection in post-kidney transplant patient with respiratory failure and Gram-negative sepsis. Clinician should put strongyloidiasis in the differential diagnosis list while dealing with critically ill post-transplant patients and add it to the pre-transplant checkup.

Keywords: Strongyloides; Septic shock; Kidney transplant

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Infections due to strongyloides stercoralis are unusual in Saudi Arabia and are usually diagnosed in immigrants from endemic areas [1]. Strongyloidiasis can be now diagnosed in non-endemic countries due to the migration flows and travel, being the infection much more common in migrants than in travelers [2].

Hyperinfection describes the syndrome of accelerated autoinfection provided the organism is confined to the organs normally involved in the pulmonary autoinfection cycle [2, 3].

Hyperinfection of this organism sometimes leads to fatal outcome because hyperinfection often occurs in patients with impaired cellular immunity. We report this case of strongyloidiasis hyperinfection presented with respiratory failure and septic shock in post-deceased kidney transplant patients.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

The patient was a 60-year-old Saudi male known to have hypertension and diabetes mellitus for 23 years complicated by end-stage renal disease for the last 2 years and required hemodialysis.

The patient was enlisted for kidney transplantation and pre-transplant checkup was all within normal. The patient received a post-deceased kidney transplant from a brain dead Pakistani gentleman. His early post-transplant course was complicated by delayed graft function and biopsy from the graft revealed acute cellular rejection. He received a pulse methylprednisolone therapy followed by tapering protocol of oral prednisolone starting with 160 mg daily.

Over next few days, there was slight improvement in the graft function, so the patient was discharged from the hospital with follow-up appointment after 4 weeks. Medication on discharge included prednisolone, mycophenolate and tacrolimus. Laboratory tests showed serum urea 21 mmol/L, creatinine 274 µmol/L, sodium 133 mmol/L, potassium 4 mmol/L and bicarbonate 23 mmol/L.

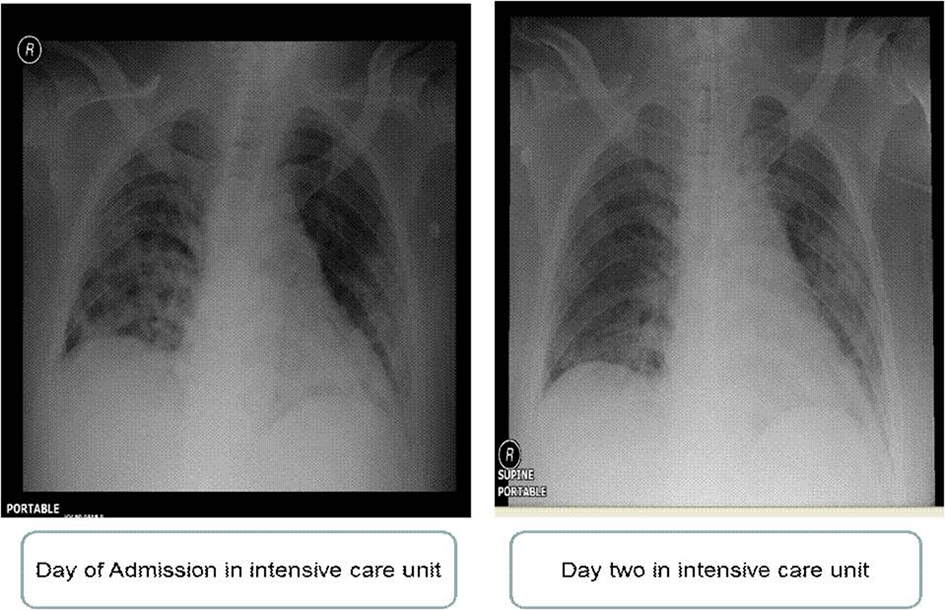

Three weeks later, he was admitted to the hospital because of severe nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain. His condition deteriorated and became more tachypneic with increasing bilateral chest infiltrates in chest X-ray (Fig. 1), so the patient was intubated and mechanically ventilated.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Chest X-ray of day of admission in intensive care unit and day 2 in intensive care unit. |

He developed ARDS with septic shock and Gram-negative (E. coli) bacteremia, and was started on Imipenm, linezolid, levofloxacin, ganciclovir and cotrimoxazol. The laboratory findings showed leucocytic count of 21.1 cc/L (91% neutrophils and 0.1% eosinophils), hemoglobin 7.3 g/dL, mild hyperbilirubinemia and normal liver function tests, bicarbonate 12 mmol/L, urea 22.5 mmol/L and creatinine 249 µmol/L.

Osephago-gastro-dudenoscopy was done, revealing esophagitis and signs of delayed gastric emptying. Bronchoscopy was performed and bronchoalvealor lavage was sent for analysis which showed parasitic larva consistent with strongyloides stercoralis associated with acute inflammatory process mainly macrophages and lymphocytes. The patient was started on albendazol 400 mg BID. With those interventions the patient’s hemodynamics and respiratory status marginally improved. However, his neurological status did not improve, despite daily sedation interruption.

Over the next few days, the patient developed refractory septic shock with acute kidney injury requiring continuous renal replacement therapy. Despite maximizing vasopressor infusions and aggressive other supportive measures, the patient condition deteriorated and he expired.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Renal transplantation has become the treatment of choice for most patients with end-stage renal disease [4]. Immunosuppression is the mainstay long-term management for post-transplant patients [5].

A group of known organisms could be reactivated or de novo infect the transplant patients, e.g. HIV, HCV and tuberculosis.

Strongyloides infections are a helminthic intestinal parasite which is endemic in tropical, sub-tropical regions affecting 30 up to 100 million worldwide.

The life cycle of strongyloides is basically comprised of two parts: a free living cycle outside of the host as rhabditiform larvae and a parasitic life cycle as infective filariform larvae (filariae) [6].

The life cycle of strongyloides infection starts by penetration of filariform larvae through skin on exposure to contaminated soil, then reaches the lung and moves to the gastrointestinal tract where they mature into female and male which mate in the intestine and produce eggs shed in stool or hatch into larvae which may re-infect the host penetrating the mucosa circulation disseminating to all organs resulting in disseminated syndrome or hyperinfection.

The source of infection in these patients seems to be either preexisting chronic infections in the recipient or from the allograft itself as in the case presented by Brugemann et al [7].

Strongyloides infection is rare in Saudi Arabia especially in good socioeconomic status like our patient so we assume that infection may be transmitted through the transplanted kidney.

Eosinophilia in strongyloidiasis might be more frequent compared to other chronic intestinal parasitic infections because the adult female worms live within the submucosa, not in the lumen of the gut [8, 9].

Low eosinophilic count and steroid use are risk factors to develop severe strongyloidiasis with high mortality rate [10].

Patients with impaired cellular immunity are also at increased risk of developing hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated infection [11]. From 1991 to 2013, more than 400 deaths due to strongyloides have been reported and about 20 reported cases strongyloides hyperinfection with mortality rate about 69%. In transplant patients, strongyloidiasis has been reported in kidney, liver, heart, intestine, pancreas and hematopoietic recipient [12].

In disseminated strongyloidiasis, the filarias spread all over body organs other than respiratory and gastrointestinal systems, for example brain [13, 14].

It may explain the encephalopathy of our patient which did not improve despite cessation of sedation, normal brain CT and normal liver function tests.

Conclusion

Strongyloides hyperinfection can happen any time after transplantation of different organs with high mortality rates. However, it seems to have predilection to strike within the first 3 months of transplantation during times of increased Immunosuppression [15].

We recommend testing for strongyloides as pre-transplant workup list in high-risk recipients and donors. Monthly prophylaxis in high-risk patients is a plausible alternative but is difficult to advocate, due to the low frequency of this disease, which makes cost-effectiveness studies challenging [16].

Further studies are needed to define the benefits of routine prophylaxis in high-risk patients. Strongyloides hyperinfection should be considered if the recipient condition deteriorated rapidly despite proper antimicrobial prophylaxis and treatment of critically ill.

Empirical antimicrobial for such critically ill should consider ivermectin and/or albendazole along with a reduction in immunosuppression.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Grant Support

Not available.

| References | ▴Top |

- Shorman M, Al-Tawfiq JA. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection presenting as acute respiratory failure and Gram-negative sepsis in a patient with astrocytoma. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13(5):e288-291.

doi pubmed - Keiser PB, Nutman TB. Strongyloides stercoralis in the Immunocompromised Population. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(1):208-217.

doi - Shapiro R, Young JB, Milford EL, Trotter JF, Bustami RT, Leichtman AB. Immunosuppression: evolution in practice and trends, 1993-2003. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(4 Pt 2):874-886.

doi pubmed - Grover IS, Davila R, Subramony C, Daram SR. Strongyloides infection in a cardiac transplant recipient: making a case for pretransplantation screening and treatment. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011;7(11):763-766.

- Yoshiaki I, Kei S, Asami M, Eiji K, Kazuto Y. A case of Strongyloides hyperinfection associated with tuberculosis. J Intensive Care. 2013;1:7.

doi - Buonfrate D, Angheben A, Gobbi F, Munoz J, Requena-Mendez A, Gotuzzo E, Mena MA,

et al . Imported strongyloidiasis: epidemiology, presentations, and treatment. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2012;14(3):256-262.

doi pubmed - Brugemann J, Kampinga GA, Riezebos-Brilman A, Stek CJ, Edel JP, van der Bij W, Sprenger HG,

et al . Two donor-related infections in a heart transplant recipient: one common, the other a tropical surprise. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29(12):1433-1437.

doi pubmed - Roxby AC, Gottlieb GS, Limaye AP. Strongyloidiasis in transplant patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(9):1411-1423.

doi pubmed - Repetto SA, Duran PA, Lasala MB, Gonzalez-Cappa SM. High rate of strongyloidosis infection, out of endemic area, in patients with eosinophilia and without risk of exogenous reinfections. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82(6):1088-1093.

doi pubmed - Fardet L, Genereau T, Poirot JL, Guidet B, Kettaneh A, Cabane J. Severe strongyloidiasis in corticosteroid-treated patients: case series and literature review. J Infect. 2007;54(1):18-27.

doi pubmed - Segarra-Newnham M. Manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(12):1992-2001.

doi pubmed - Porto AF, Neva FA, Bittencourt H, Lisboa W, Thompson R, Alcantara L, Carvalho EM. HTLV-1 decreases Th2 type of immune response in patients with strongyloidiasis. Parasite Immunol. 2001;23(9):503-507.

doi pubmed - Marcos LA, Terashima A, Canales M, Gotuzzo E. Update on strongyloidiasis in the immunocompromised host. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2011;13(1):35-46.

doi pubmed - Murali A, Rajendiran G, Ranganathan K, Shanthakumari S. Disseminated infection with Strongyloides stercoralis in a diabetic patient. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2010;28(4):407-408.

doi pubmed - Chokkalingam Mani B, Mathur M, Clauss H, Alvarez R, Hamad E, Toyoda Y, Birkenbach M,

et al . Strongyloides stercoralis and Organ Transplantation. Case Rep Transplant. 2013;2013:549038. - Abdul-Fattah MM, Nasr ME, Yousef SM, Ibraheem MI, Abdul-Wahhab SE, Soliman HM. Efficacy of ELISA in diagnosis of strongyloidiasis among the immune-compromised patients. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1995;25(2):491-498.

pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.