| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 7, Number 4, April 2016, pages 126-129

Perioperative Care of an Infant With Wolf-Hirschhorn Syndrome: Is There a Risk of Malignant Hyperthermia

Chris Humstona, Roshoyah Bernarda, Sarah Khana, b, Joseph D. Tobiasa, b, c

aDepartment of Anesthesiology & Pain Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH, USA

bDepartment of Anesthesiology & Pain Medicine, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, OH, USA

cCorresponding Author: Joseph D. Tobias, Department of Anesthesiology & Pain Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, 700 Children’s Drive, Columbus, OH 43205, USA

Manuscript accepted for publication January 18, 2016

Short title: Anesthesia and Wolf-Hirschhorn Syndrome

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14740/jmc2418w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Wolf-Hirschhorn (WH) syndrome is a rare chromosomal abnormality with deletion of the short arm of chromosome 4. Associated clinical signs and symptoms of the condition include intrauterine growth restriction, severe psychomotor retardation, failure to thrive, characteristic facial features, profound developmental delays, seizures, and various congenital midline fusion anomalies. Given the associated congenital anomalies, anesthetic care may be required for various surgical interventions. We report a 3-month-old girl with WH syndrome scheduled for gastrostomy tube placement. Previous reports of anesthetic care for such patients are reviewed and potential perioperative concerns are discussed.

Keywords: Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome; Malignant hyperthermia; Difficult airway

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Wolf-Hirschhorn (WH) syndrome is a rare chromosomal abnormality with deletion of the short arm of chromosome 4, specifically the 4p16.3 region [1]. Associated clinical signs and symptoms of the condition include intrauterine growth restriction, severe psychomotor retardation, failure to thrive, characteristic facial features, profound developmental delays, seizures and various congenital midline fusion anomalies [1-6]. The latter may include cleft lip or palate, congenital heart disease (atrial or ventricular septal defects), hypospadias and midline scalp defects [1-6]. Given the associated congenital anomalies, anesthetic care is often required for various surgical interventions. We report a 3-month-old girl with WH syndrome scheduled for gastrostomy tube placement. Previous reports of anesthetic care for such patients are reviewed and potential perioperative concerns are discussed.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Institutional Review Board approval is not required by Nationwide Children’s Hospital for presentation of single case reports. A 3-month-old, 3 kg girl presented for gastrostomy tube placement. The patient was diagnosed with WH syndrome based on intrauterine ultrasound reports and subsequent genetic testing. Chromosomal microarray showed results consistent with the diagnosis of WH syndrome. On physical examination, the child was noted to be small for her age, quiet, and hypotonic. Dysmorphic features included wide-spaced eyes, microcephaly, microstomia, a prominent glabella, low set ears, and micrognathia. Her preoperative vital signs included a resting respiratory rate of 40 breaths/min, an oxygen saturation of 99% by pulse oximetry while receiving 0.5 L/min oxygen via nasal cannula, a heart rate of 134 beats/min, and a blood pressure (BP) of 83/62 mm Hg. Preoperative echocardiography revealed an atrial septal defect. No sedative pre-medication was required. The patient had a pre-existing 24-gauge intravenous (IV) cannula in the right saphenous vein with maintenance IV fluids infusing. The patient was held nil per os for 6 h and transported to the operating room where routine American Society of Anesthesiologists’ monitors were applied. General anesthesia was induced by the administration of IV ketamine (5 mg) and atropine (0.1 mg). Sevoflurane was administered and incrementally increased to 5%. A shoulder roll was placed beneath the patient, prior to anesthetic induction, to facilitate optimal alignment of airway structures. Because of the patient’s non-reassuring airway examination, spontaneous ventilation was maintained throughout induction and endotracheal intubation. Light cricoid pressure was applied, which brought the vocal cords into view (Cormack-Lehane score of I vs. IIa). Endotracheal intubation was easily achieved using a Miller 1 blade and a cuffed, styleted 3.0 endotracheal tube. The patient tolerated anesthetic induction and endotracheal intubation without adverse hemodynamic effects. Mechanical ventilation was initiated for the case. The surgery lasted approximately 30 min. Mild hypotension occurred during the maintenance phase of anesthesia using sevoflurane (inspired concentration 2-3%), despite the administration of a 20 mL/kg fluid bolus of 0.9% NS. Therefore, the inspired concentration of sevoflurane was decreased and neuromuscular blockade was provided by the administration of rocuronium 3 mg (1 mg/kg). Fentanyl (2.5 µg/kg) was also administered. The expired concentration of sevoflurane was decreased to 1.2% in a mixture of 50% air and 50% oxygen. After completion of the surgical procedure, residual neuromuscular blockade was reversed with neostigmine and glycopyrrolate. The patient’s trachea was extubated in the operating room and she was transported to the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU). The patient was discharged from the PACU back to the neonatal ICU. The remainder of the postoperative course was uneventful. Tube feedings were started the next day based on the surgical team’s recommendations.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Patients with known genetic syndromes pose a variety of challenges to the anesthesia provider [7]. WH syndrome is an extremely rare chromosomal disorder caused by partial deletion (monosomy) of the short arm of chromosome 4. It was first described in 1961 by Hirschhorn and Cooper and subsequently published in Humangenetik by both Hirschhorn and Cooper as well as Wolf et al in 1965 [8-10]. Current estimates place the prevalence at about 1:50,000 with a 2:1 female/male ratio.

WH syndrome is characterized by a spectrum of observable abnormalities, the most important of which for the anesthesia provider include congenital heart disease and facial structural abnormalities, which may lead to difficulties with airway management. Congenital heart disease includes primarily atrial and ventricular defects. Phenotypic features include ocular hypertolerism (wide-set eyes), low-set malformed ears, micrognathia (small, recessed mandible), microcephaly (small head), prominent glabella (a “Greek helmet” appearance), broad or beaked nose, cleft lip or palate, small down turned “fish like” mouth, hypotonia, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) with a subsequent failure to thrive. Pitt-Rogers-Danks syndrome is now grouped together with WH syndrome, since both are the result of deletions on the same portion of chromosome 4, although “Pitt” syndrome generally results in milder physical and congenital abnormalities [1, 6].

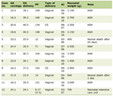

To date, there are a limited number of reports in the literature regarding the anesthetic care of patients with WH syndrome (Table 1) [11-18]. As with all anesthetic care, appropriate preoperative preparation begins with a thorough history and physical examination. Of primary concern to the anesthesia provider is the potential for difficulties with airway management and endotracheal intubation related to micrognathia, microstomia, and associate cleft lip/palate. The appropriate equipment for dealing with the difficult airway should be readily available prior to anesthetic induction, as recommended by Engelhardt and Weiss [19]. General anesthesia can be induced by the incremental inhalation of sevoflurane in 100% oxygen with the maintenance of spontaneous ventilation until the airway is secured. In our patient, we administered a small dose of ketamine to induce anesthesia and maintain spontaneous ventilation followed by the administration of incremental concentrations of sevoflurane until adequate bag-valve-mask ventilation was demonstrated. Endotracheal intubation was accomplished without the use of neuromuscular blocking agents. Airway management may be further compromised by the risk of aspiration as noted in some of the case reports which have led some to use rapid sequence intubation (RSI). However, the use of RSI must be weighed against the risks of potential difficulties with airway management and endotracheal intubation.

Click to view | Table 1. Previous Reports of Anesthetic Care in Wolf-Hirschhorn Syndrome |

While the early reports in the anesthesia literature suggested a correlation between the administration of inhaled anesthetics and the development of malignant hyperthermia (MH), more recent articles have questioned this association as there are several published reports showing that volatile agents have been used safely and without complications. Both of the patients in the two previous reports of potential MH-like symptoms had current upper respiratory infections and received high doses of atropine, muddying the picture as to whether or not it was MH, anticholinergic crisis, or active infection. When we questioned the MH hotline regarding a possible correlation between WH syndrome and the development of MH, we were told: “Although there is one report alleging an association, that has not been proven, nor do we consider that disorder a risk for MH.”

Given the associated hypotonia, another perioperative concerns is the choice of neuromuscular blocking (NMBA), especially with regard to the safety of using succinylcholine [20]. Anecdotal reports have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of succinylcholine while other reports have failed to demonstrate significant perioperative issues such as prolonged duration of action following non-depolarizing agents including vecuronium, rocuronium, and cis-atracurium [21]. Alternatively, endotracheal intubation can also be accomplished without the use of an NMBA using a combination of propofol and remifentanil or as noted in one case report, midazolam and remifentanil [22].

Seizures may be a comorbid condition in patients with WH syndrome. Preoperative management strategies to limit the potential for perioperative seizures include optimizing and confirming therapeutic anticonvulsant levels prior to the surgical procedure. Routine anticonvulsant medications should be administered the morning of the procedure despite concerns of the patient’s nil per os status with subsequent intraoperative dosing as needed. Alternative routes of delivery (IV or rectal) may be required when enteral administration is not feasible. Consultation with the neurology or pharmacology service may be helpful to determine dosing conversion from enteral to IV administration or to guide intraoperative redosing.

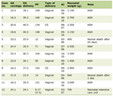

In summary, WH syndrome is a rare chromosomal abnormality with deletion of the short arm of chromosome 4. The potential perioperative implications of WH syndrome are summarized in Table 2. While initial reports suggested a predisposition to the development of MH, subsequent reports have failed to confirm this association. Other comorbid conditions which may impact perioperative care include facial anomalies which lead to difficult airway management, associated congenital heart disease, central nervous system involvement including hypotonia and underlying seizure disorder, and the potential for chronic aspiration and perioperative respiratory problems.

Click to view | Table 2. Anesthetic Concerns in Patients With Wolf-Hirschhorn Syndrome |

| References | ▴Top |

- Kant SG, Van Haeringen A, Bakker E, Stec I, Donnai D, Mollevanger P, Beverstock GC, et al. Pitt-Rogers-Danks syndrome and Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome are caused by a deletion in the same region on chromosome 4p 16.3. J Med Genet. 1997;34(7):569-572.

doi pubmed - Johnson VP, Mulder RD, Hosen R. The Wolf-Hirschhorn (4p-) syndrome. Clin Genet. 1976;10(2NA-NA-760903-760909):104-112.

- Lazjuk GI, Lurie IW, Ostrowskaja TI, Kirillova IA, Nedzved MK, Cherstvoy ED, Silyaeva NF. The Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome. II. Pathologic anatomy. Clin Genet. 1980;18(1):6-12.

doi pubmed - Battaglia A, Carey JC, Wright TJ. Wolf-Hirschhorn (4 p-) syndrome. Adv Pediatr. 2001;38:674-679.

- Zorlu P, Eksioglu AS, Ozkan M, Tos T, Senel S. A rare subtelomeric deletion syndrome: Wolf Hirschhorn syndrome. Genet Couns. 2014;25(3):299-303.

pubmed - Battaglia A, Carey JC, South ST. Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome: A review and update. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2015;169(3):216-223.

doi pubmed - Butler MG, Hayes BG, Hathaway MM, Begleiter ML. Specific genetic diseases at risk for sedation/anesthesia complications. Anesth Analg. 2000;91(4):837-855.

doi pubmed - Cooper H, Hirschhorn K. Apparent deletion of short arms of one chromosome (4 or 5) in a child with defects of midline fusion. Mammalian Chrom Nwsl. 1961;4:14-16.

- Hirschhorn K, Cooper HL, Firschein IL. Deletion of short arms of chromosome 4-5 in a child with defects of midline fusion. Humangenetik. 1965;1(5):479-482.

doi - Wolf U, Reinwein H, Porsch R, Schroter R, Baitsch H. [Deficiency on the short arms of a chromosome No. 4]. Humangenetik. 1965;1(5):397-413.

pubmed - Ginsburg R, Purcell-Jones G. Malignant hyperthermia in the Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome. Anaesthesia. 1988;43(5):386-388.

doi pubmed - Chen JC, Jen RK, Hsu YW, Ke YB, Hwang JJ, Wu KH, Wei TT. [4P- syndrome (Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome) complicated with delay onset of malignant hyperthermia: a case report]. Acta Anaesthesiol Sin. 1994;32(4):275-278.

pubmed - Sammartino M, Crea MA, Sbarra GM, Fiorenti M, Mascaro A. Absence of malignant hyperthermia in an infant with Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome undergoing anesthesia for ophthalmic surgery. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1999;36(1):42-43.

pubmed - Bosenberg AT. Anaesthesia and Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome. Southern African Journal of Anaesthesia and Analgesia. 2007;13:31-34.

doi - Iacobucci T, Nanni L, Picoco F, de Francisci G. Anesthesia for a child with Wolf-Hirshhorn syndrome. Paediatr Anaesth. 2004;14(11):969.

doi pubmed - Mohiuddin S, Mayhew JF. Anesthesia for children with Wolf-Hirshhorn syndrome: a report and literature review. Paediatr Anaesth. 2005;15(3):254-255.

doi pubmed - Schmidt J, Einhaus F, Harig F, et al. Alternative anaesthetic management of an infant with Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome during repair of an atrial septal defect using total intravenous anaesthesia. South Afr J Anesth Analg. 2010;16:6-7.

doi - Choi JH, Kim JH, Park YC, Kim WY, Lee YS. Anesthetic experience using total intra-venous anesthesia for a patient with Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome -A case report. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2011;60(2):119-123.

doi pubmed - Engelhardt T, Weiss M. A child with a difficult airway: what do I do next? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2012;25(3):326-332.

doi pubmed - Martyn JA, Richtsfeld M. Succinylcholine-induced hyperkalemia in acquired pathologic states: etiologic factors and molecular mechanisms. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(1):158-169.

doi - Azar I. The responses of patients with neuromuscular disorders to muscle relaxants: a review. Anesthesiology. 1984;61:173-187.

doi pubmed - Batra YK, Al Qattan AR, Ali SS, Qureshi MI, Kuriakose D, Migahed A. Assessment of tracheal intubating conditions in children using remifentanil and propofol without muscle relaxant. Paediatr Anaesth. 2004;14(6):452-456.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.