| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 7, Number 11, November 2016, pages 508-511

Hepatocellular Carcinoma Developed From Non-Cirrhotic Liver: A Case Report

Ryuji Imagawaa, Nobuhiro Takeuchia, e, Kazumasa Emoria, Yasuo Kamiyamab, Kaori Mohric, Shuho Sembad

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, Kobe Tokushukai Hospital, Hyogo, Japan

bDepartment of Surgery, Kobe Tokushukai Hospital, Hyogo, Japan

cDepartment of Laboratory Medicine, Kobe Tokushukai Hospital, Hyogo, Japan

dDepartment of Pathology, Kobe Ekisaikai Hospital, Hyogo, Japan

eCorresponding Author: Nobuhiro Takeuchi, Department of Internal Medicine, Kobe Tokushukai Hospital, 1-3-10 Kamitakamaru, Tarumi-Ku, Kobe-shi, Hyogo 655-0017, Japan

Manuscript accepted for publication October 26, 2016

Short title: Hepatocellular Carcinoma From Non-Cirrhotic Liver

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14740/jmc2681w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is recognized as a crucial factor in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) from non-viral cirrhosis. It is generally known that cirrhosis, fibrosis of the liver, works as a carcinogenic promoter, and it is uncommon for non-cirrhotic liver to develop into HCC. Here we report a case of HCC that developed from non-cirrhotic NASH. A 76-year-old male presented to our hospital with abdominal distention. His medical history included impaired glucose tolerance and hypertension. He denied any use of alcohol. Ultrasonography revealed a lobular mass in S5 of the liver with a marginal low echo that measured 50 × 40 mm. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography confirmed HCC. Laboratory analysis revealed normal hepatic and biliary enzymes, as well as normal levels of tumor markers, including alpha-fetoprotein and protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II. Virus markers were negative for HBs-Ag, HBV-DNA, HCV-Ab, and HCV-RNA. As a result, he was chosen as a candidate for surgical resection; subsegmental resection of S5 and S6 was performed. The resected specimens of the tumor revealed moderately differentiated HCC; rich macrovesicular lipid depositions were observed over the background liver, which was compatible with A2F1. Based on the histological findings, he was diagnosed with HCC developed from non-cirrhotic NASH. This case report is informative for clinicians by raising awareness of the potential risk of HCC in non-cirrhotic NASH.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma; Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is common in Asia and South Africa. Approximately 80-90% of HCCs arise from chronic hepatitis or liver cirrhosis that develops after HBV or HCV infections; however, a growing number of HCCs have recently developed from non-B-non-C hepatitis. Another cause of hepatitis and liver cirrhosis is non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which is related to lifestyle diseases, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), dyslipidemia, and obesity. NASH has the potential of developing HCC. Till date, HCC was believed to arise from the background of cirrhosis liver and uncommonly in a liver not damaged by cirrhosis. Here we report the case of a patient with HCC that developed from non-cirrhotic NASH.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 76-year-old male presented to our hospital with a complaint of abdominal distention. His past medical history included impaired glucose tolerance and hypertension that were treated using anti-hypertensive drugs. He denied any use of tobacco and alcohol. Non-contrast computed tomography (CT) revealed a mass of 5 cm in S5 of the liver. He was admitted to our hospital for further investigation of this liver mass.

Upon arrival, his blood pressure was 168/76 mm Hg, heart rate was 87 beats/min with regular rhythm, blood oxygen saturation was 96% under atmospheric conditions, and body temperature was 36.7 °C. On initial clinical examination, his weight was 70.7 kg, height was 170.0 cm, and body mass index (BMI) was 24.5 kg/m2. There was no evidence of anemia upon inspection of the palpebral conjunctiva. Chest auscultation revealed no signs of abnormal heart murmurs and no rales or other respiratory sounds. The abdomen was slightly distended, with no tenderness in the upper abdomen, and normal peristalsis was evident. Further, there was no palpable mass or any signs of peritoneal irritation.

Laboratory analysis results, including complete blood counts, biochemistry, and blood coagulation values were all within normal limits. In addition, tumor markers, including alpha-fetoprotein and protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II, revealed values within normal limits. Virus markers were negative for HBs-Ag, HBV-DNA, HCV-Ab, and HCV-RNA.

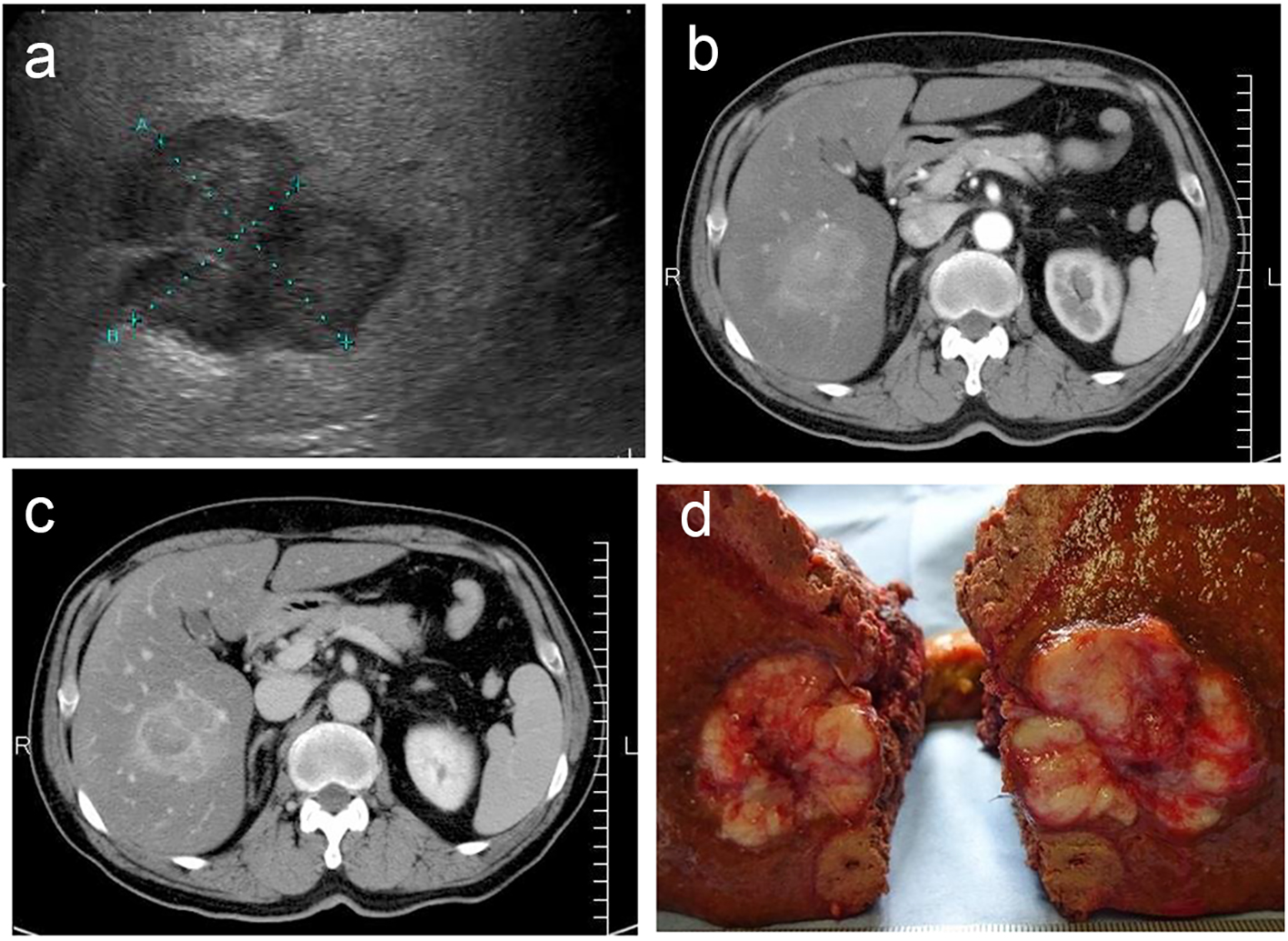

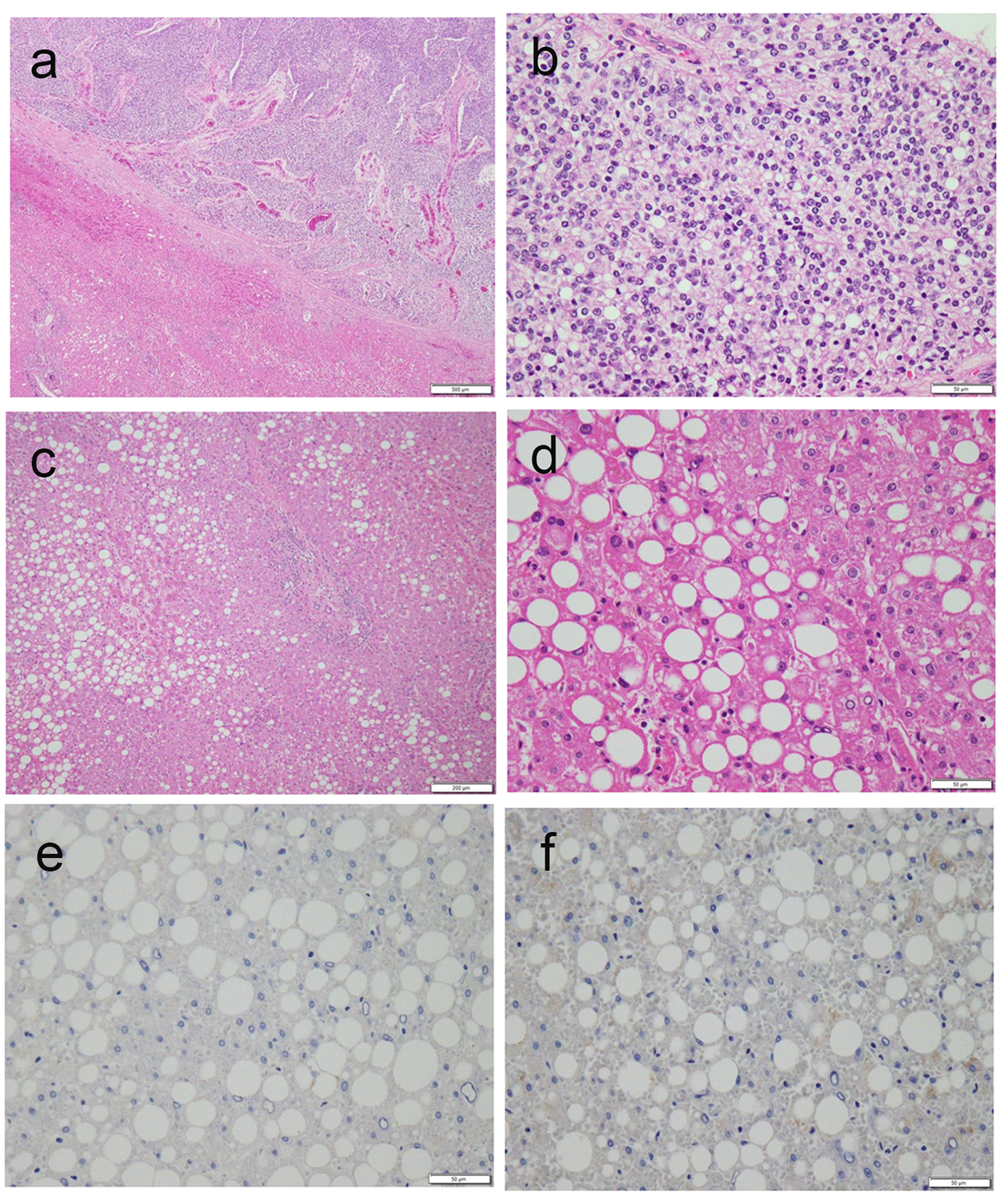

Ultrasonography revealed a lobular mass in S5 of the liver with a marginal low echo that measured 50 × 40 mm (Fig. 1a). Contrast-enhanced CT also revealed a mass in S5 of the liver that measured 48 × 45 × 45 mm, with marked enhancement in the early phase (Fig. 1b). In the late phase, contrast agents in the interiors of the mass were washed out with the residues of the contrast agent at the margin of the tumor (Fig. 1c). Based on the imaging modalities, the patient was diagnosed with HCC. As a result, he was chosen as a candidate for surgical resection. Subsegmentectomy of S5 and S6 was performed under general anesthesia. Gross examination of the specimen revealed a white-yellowish soft tumor with multiple nodules (Fig. 1d). Microscopic histological findings of the tumor indicated moderately differentiated HCC (low power fields, Fig. 2a; high power fields, Fig. 2b). In addition, macrovesicular lipid depositions and mild steatosis without fibrosis were observed in the background liver, which were compatible with A2F1 (low power fields, Fig. 2c; high power fields, Fig. 2d).

Click for large image | Figure 1. (a) Ultrasonography revealed a lobular mass in S5 of the liver with a marginal low echo, measuring 50 × 40 mm. (b) Contrast-enhanced CT revealed a mass in S5 of the liver, measuring 48 × 45 × 45 mm, with marked enhancement in the early phase. (c) Contrast agents in interiors of the mass were washed out in the late phase with the residues of the contrast agent at the margin of the tumor. (d) Gross specimen revealed a white-yellowish soft tumor with multiple nodules. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. (a, b) Microscopic histological findings of the tumor revealed moderately differentiated HCC (a, low power fields; b, high power fields). (c, d) Macrovesicular lipid depositions and mild steatosis without fibrosis were observed in the background liver, compatible with A2F1 Inuyama classification (c, low power fields; d, high power fields). (e, f) Immunostaining of background liver tissues by HBs-Ag and HBc-Ag revealed negative and false-positive results, respectively. |

The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient discharged, and regular follow-up at an outpatient clinic was planned.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Approximately 80-90% of HCCs in Japan arise from HBV- or HCV-related chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis; however, there has been an increasing number of non-B-non-C HCCs. NASH is considered to be another potential cause of hepatitis and liver cirrhosis and also deemed to be an underlying non-B-non-C HCC disease. Past research has demonstrated strong associations between NASH and lifestyle diseases. Increase in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) has been found to have a positive correlation with liver fibrosis, suggesting that the level of HbA1c affects the progression of NASH [1].

Liver damage that is not associated with a history of alcoholic use, which shares similar histological findings to alcohol-associated liver disease, was discovered in 1980; thus, the concept of NASH was first established [2]. Subsequently, the relationship of NASH with metabolic syndromes, including obesity, DM, and hypertension, was observed [3]. Although it was considered uncommon for non-cirrhosis NASH to develop into HCC, there has been an increasing number of cases of HCC developed from NASH. Recently, it was reported that oxidative DNA damage may, in part, be a carcinogen [4]. Furthermore, patients with metabolic syndrome suffering from obesity, DM, hypertension, and dyslipidemia tend to demonstrate increased oxidative stress [5].

A recent pathological study regarding NASH complicated by HCC demonstrated that 64% of HCCs arose from non-cirrhotic liver [6]. This finding may suggest that fatty liver has a high potential for developing HCC. Recently, the concept of “immunometabolism” has gained momentum as a potential pathway to the development of HCC, stemming from complicated changes in the immunosystem or metabolic malfunction. Hence, immunometabolism is considered an important factor in the development of HCC from non-cirrhotic liver.

In the current study, closer examination of virus markers in the patient showed a positive indicator for HBs-Ab and negative indicator for HBc-Ab, HBe-Ag, and HBe-Ab. Although it is unclear if the present patient had a history of HBV vaccination, it is possible that he contracted HBV without being aware of it, indicating that acute HBV-related hepatitis might remit before knowing. Immunostaining of background liver tissues by HBs-Ag and HBc-Ag revealed negative and false-positive results, respectively (Fig. 2e, f). Based on this result, it seems likely that HBV viruses undetectable by serologic tests are involved in liver tissues. Upon further examination of liver fibrosis in this patient, the serum hyaluronic acid and serum collagen type IV levels were within normal limits; this result suggests no evidence of liver fibrosis in this patient. According to studies of asymptomatic HBV carriers, chronic HBV hepatitis, and HBV cirrhosis, it is known that negative seroconversion rates of HBV infections are 1-2%/year [7]. Despite the amelioration of liver tissues in patients with HBV remission after the seroclearance of HBs-Ag, serum HBV-DNA and the normalization of serum ALT levels, it is possible for HCC to occur [8, 9]. It is recognized that HBV-DNA in liver tissues may work as a carcinogen, even if serum HBV-DNA is not detected. Recently, the concept of occult HBV has received attention after the revelation of fulminant HBV hepatitis developed during immunosuppressive therapy or chemotherapy [10]. Occult HBV is defined as absence of HBs-Ag and presence of HBc-Ab and/or HBs-Ab; it carries a risk of reactivation of HBV hepatitis [11]. In our patient, it was challenging to differentiate whether HCC stemmed from NASH or from occult HBV; nonetheless, it is suggested that patients with positive HBc-Ab and/or positive HBs-Ab, or positive HBs-Ab and/or positive HBc-Ab should receive regular follow-ups with serological viral marker testing and imaging modalities. Moreover, it should be noted that patients with metabolic syndrome should be meticulously observed by ultrasonography despite results of hepatitis virus markers.

A randomized control trial demonstrated that weight loss by diet and exercise is effective for the amelioration of liver steatosis [12]. Likewise, in our patient, weight management and control of blood pressure and blood sugar levels is important for ameliorating NASH and preventing HCC recurrence.

Conclusion

There is a growing concern about NASH as a contributing factor in the development of non-viral hepatitis or cirrhosis. NASH should be carefully observed because it carries a potential risk of developing HCC regardless of history of non-cirrhotic liver. Moreover, whenever encountering HCC with negative indicators for serum HBs-Ag and HCV-Ab, it is important to examine serum HBc-Ab and HBs-Ab to determine the presence of occult HBV. Our findings suggest that clinicians should increase awareness of these growing concepts of NASH and occult HBV.

| References | ▴Top |

- Yasui K, Hashimoto E, Komorizono Y, Koike K, Arii S, Imai Y, Shima T, et al. Characteristics of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis who develop hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(5):428-433; quiz e450.

- Ludwig J, Viggiano TR, McGill DB, Oh BJ. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo Clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980;55(7):434-438.

pubmed - Bacon BR, Farahvash MJ, Janney CG, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: an expanded clinical entity. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(4):1103-1109.

doi - Hashimoto E, Yatsuji S, Kaneda H, Yoshioka Y, Taniai M, Tokushige K, Shiratori K. The characteristics and natural history of Japanese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol Res. 2005;33(2):72-76.

doi pubmed - Roberts CK, Sindhu KK. Oxidative stress and metabolic syndrome. Life Sci. 2009;84(21-22):705-712.

doi pubmed - Yoshitaka Takuma, Kazuhiro Nouso. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-associated hepatocellular carcinoma: Our case series and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(12):1436-1441.

doi pubmed - Chu CM, Liaw YF. Hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance during chronic HBV infection. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(2):133-143.

doi pubmed - Yuen MF, Wong DK, Sablon E, Tse E, Ng IO, Yuan HJ, Siu CW, et al. HBsAg seroclearance in chronic hepatitis B in the Chinese: virological, histological, and clinical aspects. Hepatology. 2004;39(6):1694-1701.

doi pubmed - Tong MJ, Nguyen MO, Tong LT, Blatt LM. Development of hepatocellular carcinoma after seroclearance of hepatitis B surface antigen. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(8):889-893.

doi pubmed - Zhang B, Wang J, Xu W, Wang L, Ni W. Fatal reactivation of occult hepatitis B virus infection after rituximab and chemotherapy in lymphoma: necessity of antiviral prophylaxis. Onkologie. 2010;33(10):537-539.

doi pubmed - Zeinab Nabil, Ahmed Said. An overview of occult hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(15):1927-1938.

doi pubmed - Promrat K, Kleiner DE, Niemeier HM, Jackvony E, Kearns M, Wands JR, Fava JL, et al. Randomized controlled trial testing the effects of weight loss on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):121-129.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.