| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 9, Number 1, January 2018, pages 1-4

A Case of Tropical Eosinophilia in a Foreign Worker in Singapore

Veeraraghavan Meyyur Aravamudana, f, Phang Kee Fongb, Pavel Singhc, Chong Chern Haod, Yang Shiyao Samb, Ikram Hussaind, James Steven Moltone

aDepartment of Medicine, Woodlands Integrated Health Campus (WIHC), Singapore

bDepartment of Medicine, National University Hospital, Singapore

cDepartment of Diagnostic Radiology, National University Hospital, Singapore

dDepartment of Gastroenterology, Woodlands Integrated Health Campus (WIHC), Singapore

eDepartment of Infectious Disease, National University Hospital, Singapore

fCorresponding Author: Veeraraghavan Meyyur Aravamudan, Department of Medicine, Woodlands Integrated Health Campus (WIHC), Singapore

Manuscript submitted October 31, 2017, accepted November 23, 2017

Short title: Tropical Eosinophilia in a Foreign Worker

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc2954w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia (TPE) is a rare, but well recognized syndrome characterized by pulmonary interstitial infiltrates and marked peripheral eosinophilia. Early recognition and treatment with the antifilarial drug, diethylcarbamazine, is important, as delay before treatment may lead to progressive interstitial fibrosis and irreversible impairment. Here, we present a case of patient who presented with respiratory tract symptoms and marked eosinophilia. He was diagnosed with TPE from filariasis and was treated with antifilarial medications, leading to a full recovery.

Keywords: Peripheral eosinophilia; Diethylcarbamazine; Lung fibrosis

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia (TPE) is a difficult diagnosis to make. This requires a high index of clinical suspicion, and should be considered in patients who present with peripheral eosinophilia together with respiratory tract symptoms, particularly when they come from areas which are highly endemic for filiaria. This condition is more widely recognized and promptly diagnosed in filariasis-endemic regions, such as the Indian subcontinent, Africa, Asia and South America. In non-endemic countries, patients are commonly thought to have bronchial asthma. Chronic symptoms may delay the diagnosis by up to many years.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Our patient is a 31-year-old Indian man who works as a welder. He came from the Northern part of India but has lived and worked in Singapore for the past 8 years. He presented with wheezing and intermittent shortness of breath, and early morning cough for 6 months. He was initially given a presumptive diagnosis of asthma and treated with inhalers together with a short course of prednisolone and antibiotics, to no avail for the past 8 months.

He had no significant past medical history. There were also no alarm signs like hemoptysis, fever and weight loss, or exposure to tuberculosis (TB) contacts. He did not smoke or drink alcohol, nor was he on any long term medications. He did not own any pets.

On examination, heart sounds were normal. The respiratory exam revealed bilateral crepitations and expiratory rhonchi. His abdomen was soft, non-tender, with no palpable masses. There was no cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy. There were no neurological deficits and stigmata of liver disease.

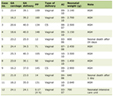

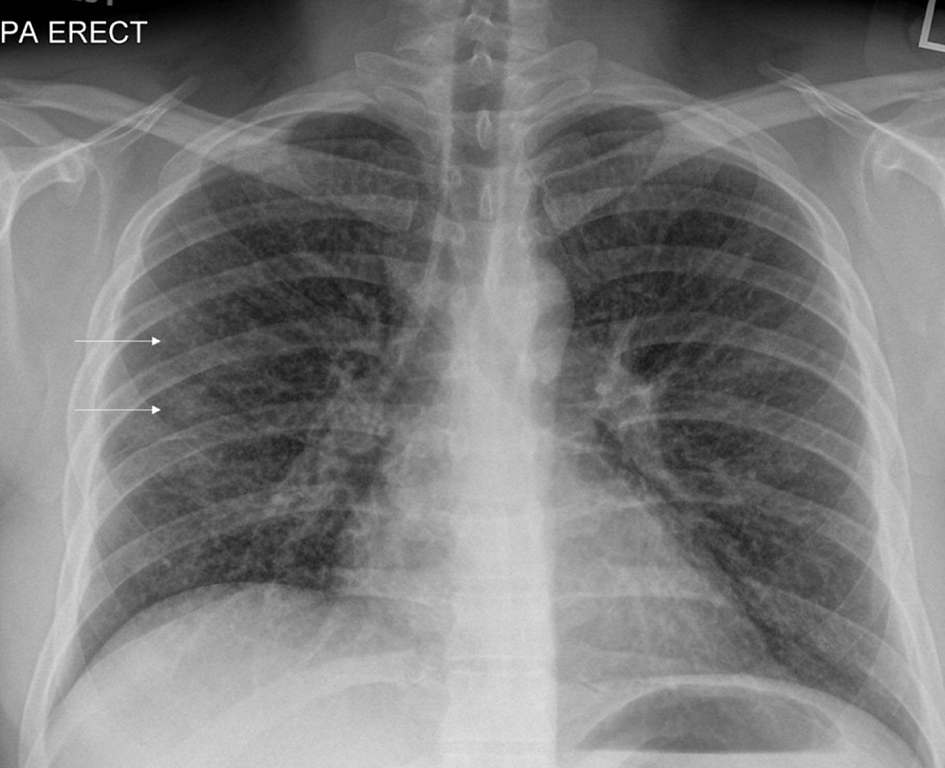

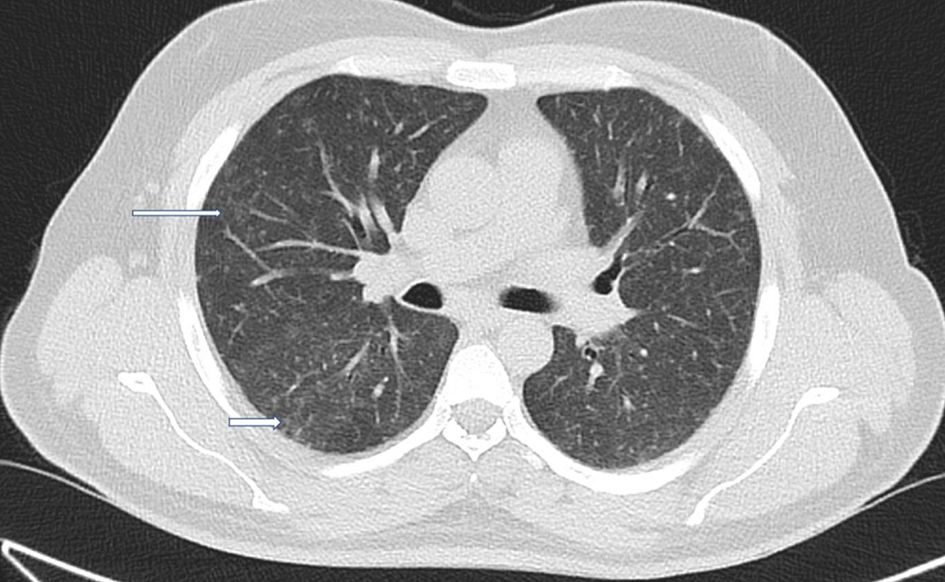

Investigations demonstrated leukocytosis 28,500/µL with marked eosinophilia 21,500/µL, other blood results are summarized in Table 1. Chest radiography demonstrated tiny clustered nodular opacities in both lungs (Fig. 1). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the thorax (Fig. 2) was performed which showed diffuse tiny scattered pulmonary nodularities with peripheral ground glass opacities and areas of scarring. He also had a raised serum Ig E of 15,000 international units (IU)/mL. Bronchoalveolar lavage showed a nucleated cell count of 3,430/µL with eosinophilic predominance of 61%. Cultures were otherwise negative.

Click to view | Table 1. Initial Blood Test Results |

Click for large image | Figure 1. Pre-treatment chest X-ray showing clustered tiny nodular opacities in both lungs (white arrows). |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Axial and coronal sections of lungs showing clustered tiny nodular opacities in both lungs (thin white arrows). Also seen are patchy areas of ground glass changes and early scarring bilaterally (thick white arrows). |

As such, this clinical presentation of chronic cough and marked radiological changes in the lungs and together with marked peripheral eosinophilia, TPE was considered. Other tests to explain eosinophilia, such as stool tests for ova, cysts and parasites, were negative. Filariasis IgG serology was positive of 18.65units (reference range: < 1.50 negative, 1.5 - 3 equivocal and > 3 strongly positive) and he was treated with diethylcarbamazine (DEC) and prednisolone for 3 weeks.

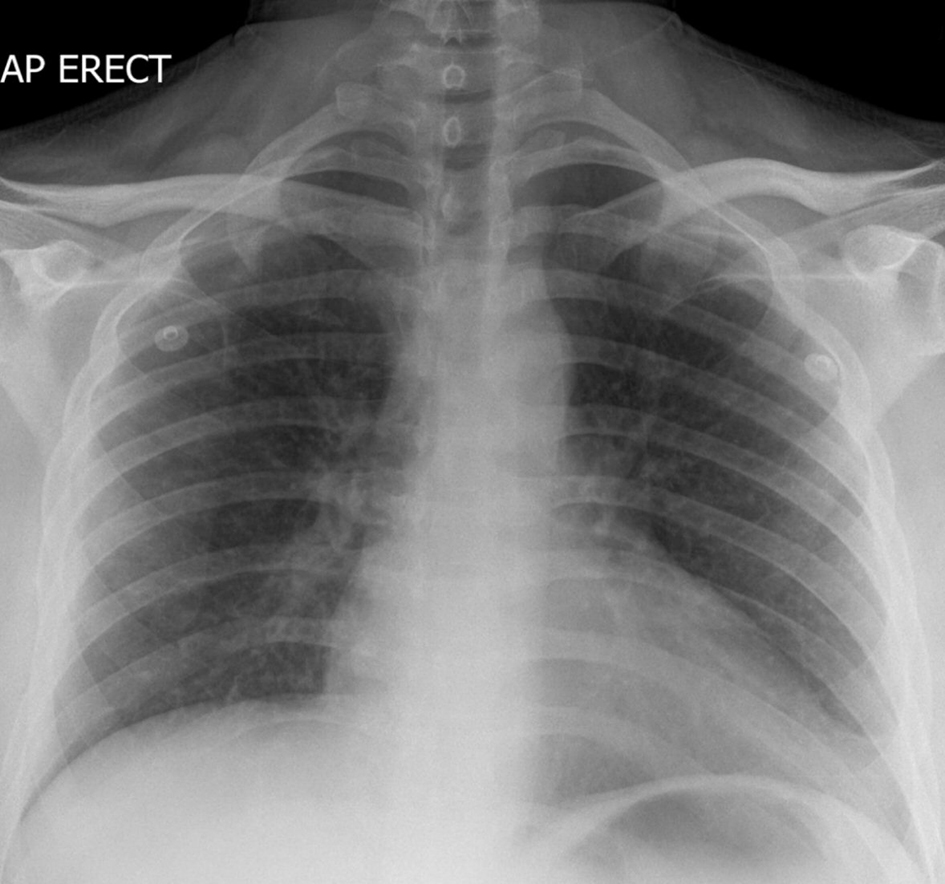

He was reviewed in clinic 3 weeks later with complete resolution of his symptoms and normalization of eosinophil counts. Three weeks later he had repeat chest X-ray (Fig. 3) which showed complete resolution of previously seen tiny nodular opacities.

Click for large image | Figure 3. Post-treatment chest X-ray showing complete resolution of previously seen tiny nodular opacities. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

TPE is a syndrome of wheezing, fever and eosinophilia seen predominantly in the Indian subcontinent and other tropical areas. Its etiological link with Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia malayi has been well established [1].

Cases have been reported from non-endemic regions such as Japan, Netherlands, The United Kingdom and Australia, probably as a result of travel to or immigration from endemic areas [2]. Persons traveling to endemic areas are considered to be at a risk, and they may be more prone as they lack natural immunity to filarial antigens.

The pathogenesis is due to an exaggerated immune response to the filarial antigens which includes type I, type III and type IV hypersensitivity reactions with eosinophils playing a pivotal role [3]. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is usually striking [4]. High serum levels of IgE and filarial-specific IgE and IgG are also found.

Lymphatic filariasis may involve multiple body systems but predominantly affects the lungs. Systemic symptoms include fever, weight loss, fatigue and malaise. Extrapulmonary manifestations include lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. Cor pulmonale does not occur and electrocardiograph (ECG) changes are non-specific. Neurologic involvement is not known. Wheezes and crackles may be found on examination.

On chest imaging, a small percentage of TPE patients have been found to have normal radiographs. The larger percentage, however, manifests with symptoms such as reticulonodular shadows.

The diagnostic criteria for TPE are as follows [1]: 1) a history suggestive and supportive exposure to lymphatic filariasis together with an elevated serum IgE level of more than 1,000 kU/L and a peripheral eosinophilia over 3 × 109/L; 2) there also should be increased titers of anti-filarial antibodies and a clinical response to DEC. Other confirmatory tests include an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test to detect the Og4C3 antigen which is sensitive and specific for W. bancrofti infections. This test, however, fails to detect Brugia malayi infection. For this, another test called the sandwich ELISA detects antibodies to the recombinant antigen Bm-SXP-1 is used [5].

The histopathological reactions observed were mainly classified into three types [1]: 1) acute eosinophilic infiltration, 2) mixed cell infiltrate (eosinophils and histiocytes) with generally well-marked fibrous tissue formation, and 3) histiocytic infiltration and fibrosis beyond 2 years.

The use of DEC is considered as the first-line therapy in the treatment of TPE. Albendazole which is also given alongside this therapy increases the efficacy of either drug. These drugs are used in combination, and they act as the basis of long-term, community-directed interventions aimed at stopping and preventing disease transmission. However, DEC is contraindicated in many parts of Africa due to co-endemicity of onchocerciasis.

Conclusions

TPE is a hypersensitivity reaction to filarial antigens. The key presenting characteristic is eosinophilic alveolitis which develops into breathlessness with exertion with time. Fibrosis occurs in the untreated individual with time. Lung function displays an increase in restriction. The peripheral eosinophilia may decrease hence rendering it difficult to make a correct inference without data from the natural history.

Clinicians should suspect tropical eosinophilia when there is a history suggestive and supportive exposure to lymphatic filariasis together with an elevated serum IgE level of more than 1,000 kU/L and a peripheral eosinophilia. There also should be increased titers of anti-filarial antibodies and a good clinical response to DEC.TPE may involve multiple body systems but predominantly affects the lungs.

Conflict of Interest

All authors have no disclosures to make directly related to the study and no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

VMA, PKF, CCH, YSS and IH helped in compilation of the text and literature search. PS helped in radiological images and literature search. JSM helped in the compilation of the text, literature search and in editing the manuscript.

Financial Support

None.

| References | ▴Top |

- Mullerpattan JB, Udwadia ZF, Udwadia FE. Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia - A review. The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2013;138(3):295.

pubmed - Andrea K. Boggild, Jay S. Keystone, Kevin C. Kain. Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia: a case series in a setting of non endemecity. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2004;39:1123-1128.

doi pubmed - Ottesen EA, Neva FA, Paranjape RS, Tripathy SP, Thiruvengadam KV, Beaven MA. Specific allergic sensitsation to filarial antigens in tropical eosinophilia syndrome. Lancet. 1979;1(8127):1158-1161.

doi - Weingarten RJ. Tropical eosinophilia. Lancet. 1943;1:103-105.

doi - Rocha A, Lima G, Medeiros Z, Aguiar-Santos A, Alves S, Montarroyos U, Oliveira P, et al. Circulating filarial antigen in the hydrocele fluid from individuals living in a bancroftian filariasis area - Recife, Brazil: detected by the monoclonal antibody Og4C3-assay. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004;99(1):101-105.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.