| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 9, Number 1, January 2018, pages 16-18

Trigemino-Cardiac Reflex and High-Degree Atrioventricular Block in Recurrent Epistaxis

Aaron Richlera, c, Carlos Morales-Manguala, Hymie Cherab, Uzma Alia, Jason Lazarb, Mark Stewartb, Moshe Gunsburga, Yitzhak Rosena, b

aDivision of Cardiovascular Medicine, Cardiac Electrophysiology Unit, Brookdale University Hospital, 1 Brookdale Plaza, Brooklyn, NY 11212, USA

bDivision of Cardiovascular Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, 470 Clarkson Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11203, USA

cCorresponding Author: Aaron L. Richler, Brookdale University Hospital and Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY 11219, USA

Manuscript submitted November 2, 2017, accepted November 23, 2017

Short title: Recurrent Epistaxis

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc2957w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

We present a case of a 55-year-old male who presented to emergency department with recurrent epistaxis. After placement of a 16-French Foley catheter in his right nare to tamponade the bleeding, the patient subsequently developed two episodes of syncope. Review of the telemetry rhythm strips showed that he had developed PR interval prolongation followed by complete atrioventricular block. Our case was likely secondary to stimulation of the trigemino-cardiac reflex, a neuro-cardiogenic reflex, that can occur after stimulation of the trigeminal nerve, whether centrally or peripherally. Patients can develop severe bradycardia, hypotension, asystole, and even death. The relatively common occurrence of epistaxis and its treatment with direct nasal tamponade require an increased awareness and possibly a requirement for telemetry monitoring to prevent complications from stimulation of this reflex.

Keywords: Trigemino-cardiac reflex; Complete heart block; Epistaxis; Trigeminal nerve; Bradycardia; Gasserian ganglion; Diving reflex

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The trigemino-cardiac reflex (TCR) is a neuro-cardiogenic reflex, which can occur after stimulation of the trigeminal nerve, whether centrally or peripherally. When stimulated, patients can develop severe bradycardia, hypotension, asystole, and even death.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

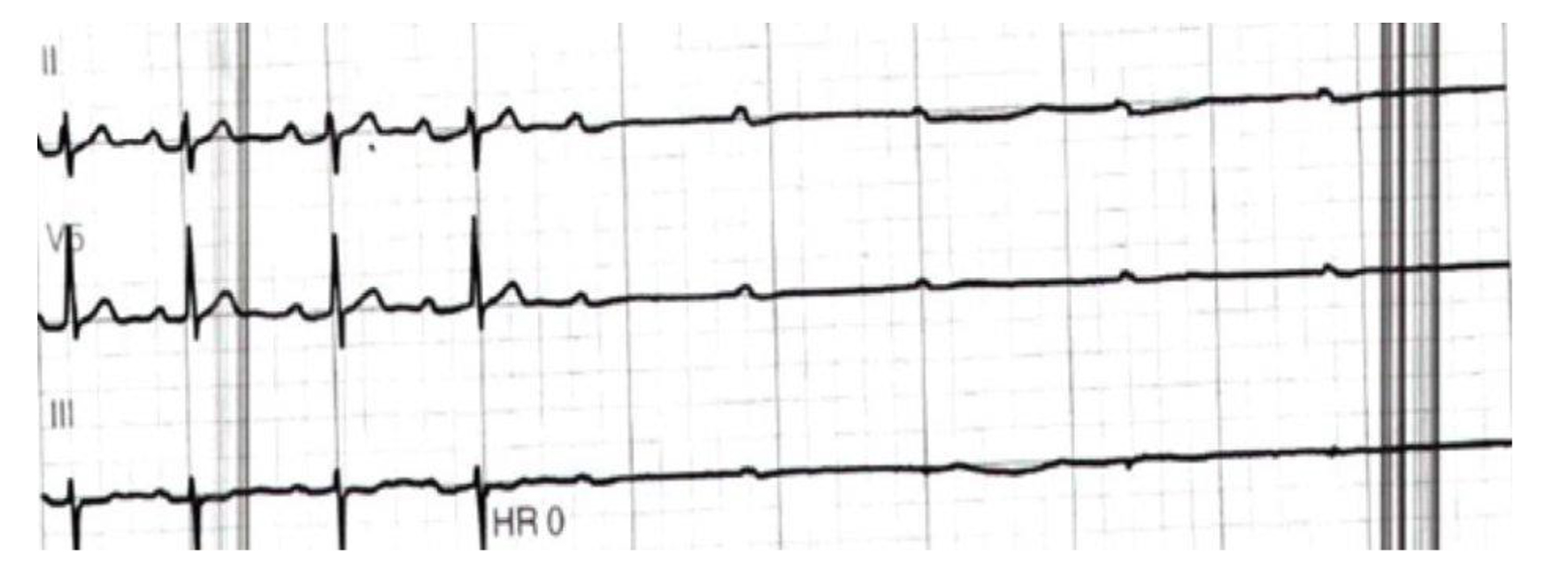

A 55-year-old male with past medical history of hypertension and asthma was admitted to the hospital and later to the surgical intensive care unit for recurrent epistaxis. The patient had a 16-French Foley catheter placed in his right nare by the otorhinolaryngology service, which stopped the bleeding. On the second day of admission while standing at the bedside with the Foley catheter in place, he got out of bed in attempt to find a bathroom, but the nurse told him to return to the bed. After he laid down, he lost consciousness, preceded by diaphoresis, tachypnea, hypotension, and tachycardia. Review of the telemetry rhythm strips showed that he had developed PR interval prolongation followed by complete atrioventricular (AV) block. Two hours later, he had a repeat episode after manipulation of the catheter within the right nare. Again, review of the rhythm strip revealed PR prolongation followed by complete AV block (Fig. 1). His blood glucose level taken immediately following each episode was more than 120 mg/dL. He had no documented history of allergies. His home medications included nifedipine Xl 60 mg daily and metoprolol tartrate 25 mg twice daily.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Leads II, III and V5 tracings showing progressive PR prolongation followed by complete atrioventricular block. |

Vital signs and laboratory results prior to event showed blood pressure of 174/103 mm Hg, pulse of 84 bpm, temperature of 37.1 °C (98.8 °F) (oral), respiratory rate of 28 per minute, PT of 10.2 s, PTT of 31.9 s, INR of 0.9, WBC of 5.90 × 109/L, HBG of 16.2 g/dL, HCT of 49.7%, PLTs of 201 × 109/L, glucose of 107 mg/dL, BUN of 15.0 mg/dL, creatinine of 0.90 mg/dL, sodium of 141 mEq/L, potassium of 4.2 mEq/L, troponin of 0.012 ng/mL, CPK 160 U/L, and Mg of 1.7 mg/dL.

Hospital course

The patient was transferred to the telemetry unit where the nasal catheter was removed. Thereafter, he had no further recurrences of heart block or syncope while on telemetry monitoring. He was able to ambulate on the unit without any symptoms. An electrophysiology consult stated that the episode of PR prolongation followed by complete AV block was likely triggered by the TCR precipitated by manipulation of the catheter and the resulting pressure. A subsequent treadmill exercise stress test showed excellent chronotropic competence, with no heart block before, during or after exercise. The PR interval remained normal throughout. A 24-h Holter monitor showed episodes of sinus tachycardia with 1:1 AV conduction and a normal PR interval. Echocardiography showed no evidence of structural heart disease. Based upon these findings, it was felt that the patient required no further testing and was discharged home.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Epistaxis is very prevalent, especially in the emergency department occurring at least once in 60% of the US population with a bimodal age distribution less than 18 or older than 50 years [1, 2]. Most commonly, the bleeding is from the anterior nasal septum with Kiesselbach’s plexus as a source [1, 2]. When this plexus is manipulated, stimulation of the sensory branches of the trigeminal nerve can occur and activate the TCR [3-7]. The TCR, also referred to the Kratschmer’s reflex was first coined by Florian Kratschmer (1843 - 1922) who reported changes in breathing, blood pressure, and heart rate when mucosa within the nasal airways are stimulated [7]. Later, the term TCR was used and its definition included afferent pathways originating in key sensory branches of the trigeminal nerve and efferent activation of the parasympathetic nervous system to cause dysrhythmia and/or gastric hypermotility [5]. A decreased sympathetic outflow is associated with a reduction by 20% or more of mean arterial pressure from baseline, and apnea can also occur. The stimulation can involve mechanical, electrical or chemical manipulation of any of the branches of the trigeminal nerve with the exclusion of noxious stimuli. Typically, it takes 5 s from the stimulus initiation to the development of bradycardia and decrease in mean arterial blood pressure. Once the stimulus stops, heart rate and blood pressure return to baseline. It should be noted that anticholinergic and trigeminal nerve blocks eliminate the TCR [3-7].

Anatomically, the TCR pathway is comprised of the central (proximal) or peripheral (distal) part of the trigeminal nerve (CNV). The central portion includes the Gasserian ganglion up until the brainstem. The peripheral portion includes the three branches of the trigeminal nerve distal to the Gasserian ganglion. Interestingly, stimulating the Gasserian or the central portion of the nerve produces a decrease in both heart rate and mean arterial pressure. However, stimulating the peripheral portion produces a decrease in heart rate as well as either an increase or decrease in mean arterial blood pressure. This is due to the close proximity of parasympathetic and sympathetic nerve fibers, which affect blood pressure control. The decrease in heart rate in TCR involves the activity of the cardio-inhibitory efferent fibers which include the motor nucleus of the vagus nerve relaying to the cardiac muscle and synapse mainly at the sinoatrial (SA) and AV node [4-7].

Several risk factors have been identified. These include hypercapnia, hypoxemia, light general anesthesia, abrupt and sustained traction stimuli, and medications. Medications include sufentanil, alfentanil, beta-blockers, and calcium channel blockers [4, 6, 7]. Lang et al presented a small case series, which occurred during maxillofacial surgery. Interestingly, one of the cases reported a ventricular asystole for 3 s occurred every time the osteome was used to manipulate the maxillary bone [8]. In another case described by Awasthi et al patient admitted for epistaxis while on warfarin for pulmonary embolism required nasal packing with gauze. After 15 min of nasal packing advance cardiopulmonary support intervention was started and patient died shortly afterward [9]. There is another neurogenic reflex that causes bradycardia called the “diving reflex” (DR). This reflex occurs in response to breathholding and is further augmented with subsequent contact of the face with cold water. It consists of apnea, bradycardia, and peripheral vasoconstriction, decreased cardiac output and increased mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) [10]. These responses conserve oxygen for vital organs such as the heart and brain. Ultimately the DR can be considered a part of the peripheral TCR; however, one significant difference is that in the DR, the MABP increases once stimulated in addition to apnea occurring. However, the TCR is defined as a 20% decrease in MABP [5].

In conclusion, the TCR can occur with stimulation of all branches of the trigeminal nerve, whether centrally or peripherally by various stimuli. Patient can develop severe bradycardia, hypotension, asystole, and even death. The course of events that occurred with our patient was likely a stimulation of the TCR through stimulation of the maxillary branch (V2) by the catheter used for tamponade. The relatively common occurrence of epistaxis and its treatment with direct nasal tamponade require increased awareness and possibly a requirement for telemetry monitoring to prevent complications from stimulation of his reflex.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors has any conflict of interest with the contents.

| References | ▴Top |

- Pallin DJ, Chng YM, McKay MP, Emond JA, Pelletier AJ, Camargo CA, Jr. Epidemiology of epistaxis in US emergency departments, 1992 to 2001. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(1):77-81.

doi pubmed - Viducich RA, Blanda MP, Gerson LW. Posterior epistaxis: clinical features and acute complications. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25(5):592-596.

doi - Spiriev T, Sandu N, Arasho B, Kondoff S, Tzekov C, Schaller B, Trigemino-Cardiac Reflex Examination G. A new predisposing factor for trigemino-cardiac reflex during subdural empyema drainage: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:391.

doi pubmed - Chowdhury T, Sandu N, Meuwly C, et al. Trigeminocardiac reflex: differential behavior and risk factors around the course of the trigeminal nerve. Future Neurol. 2014;9:41-47.

doi - Schaller BJ, Filis A, Buchfelder M. Trigemino-cardiac reflex in humans initiated by peripheral stimulation during neurosurgical skull-base operations. Its first description. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2008;150(7):715-717; discussion 717-718.

doi pubmed - Arasho B, Sandu N, Spiriev T, Prabhakar H, Schaller B. Management of the trigeminocardiac reflex: facts and own experience. Neurol India. 2009;57(4):375-380.

doi pubmed - Kratschmer F. On reflexes from the nasal mucous membrane on respiration and circulation. Respir Physiol. 2001;127(2-3):93-104.

doi - Lang S, Lanigan DT, van der Wal M. Trigeminocardiac reflexes: maxillary and mandibular variants of the oculocardiac reflex. Can J Anaesth. 1991;38(6):757-760.

doi pubmed - Awasthi D, Roy TM, Byrd RP Jr. Epistaxis and death by the trigeminocardiac reflex: a cautionary report. A case of trigeminocardiac reflex following nasal packing for epistaxis led to respiratory and cardiac arrest and patient death. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 2015;32(6):73-77.

- Lemaitre F, Chowdhury T, Schaller B. The trigeminocardiac reflex - a comparison with the diving reflex in humans. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11(2):419-426.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.