| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 10, Number 3, March 2019, pages 75-77

Experience of End-of-Life Home Care in an Acute General Community Hospital in Japan

Hideaki Kawabataa, f, Kazumi Kitamurab, Yoshiki Yamamotoc, Yohei Okamotod, Ayaka Shimajie, Kaoru Aokib, Yoko Katob, Yoko Tokuyamae, Yoshihiro Shimizuc

aDepartment of Gastroenterology, Kyoto Okamoto Memorial Hospital, Kyoto, Japan

bDepartment of Nurse, Kyoto Okamoto Memorial Hospital, Kyoto, Japan

cDepartment of Surgery, Kyoto Okamoto Memorial Hospital, Kyoto, Japan

dDepartment of Psychiatry, Kyoto Okamoto Memorial Hospital, Kyoto, Japan

eDepartment of Pharmacy, Kyoto Okamoto Memorial Hospital, Kyoto, Japan

fCorresponding Author: Hideaki Kawabata, 58 Nishinokuchi, Sayama, Kumiyama-cho, Kuze-gun, Kyoto 613-0034, Japan

Manuscript submitted January 24, 2019, accepted February 11, 2019

Short title: End-of-life Home Care in General Hospital

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3263

| Abstract | ▴Top |

We sometimes encounter situations in which it is impossible to find appropriate home care clinics despite patients’ wish of spending end of life (EOL) at home. We herein report our experience in cases of EOL home-based care managed by medical staff in an acute general community hospital. We retrospectively reviewed the clinical data of five cancer patients who received EOL home care managed by our institution between May 2016 and October 2018. We assessed the background characteristics and clinical course, how medical staff managed the patients and degree of satisfaction in the EOL care we provided, based on impressions interviews with the patients and their families. The median duration between the final examination by doctors in the hospital and death was 5 days (range: 7 h - 5 days). Regarding the visits to the four patients other than the one who died during her outing, home-visit nurses visited the patients’ homes every day in three of four patients, and both a care manager and a medical social worker (MSW) tried to evaluate the condition of the remaining patient by visits and phone calls. Information on the patients’ condition at home was given to the medical staff in order to discuss optimal home care. When they died, a doctor, a home-visit nurse, a nurse belonging to the palliative care team and a MSW visited in all cases. All patients spent their EOL calmly at home, and their families were pleased with their EOL and grateful to the medical staff who supported the patients. We supported patients’ EOL by managing home-based medical care in cooperation with multi-occupational staff. We should organize a system for meeting patients’ changing wishes flexibly.

Keywords: End-of-life home care; Deathbed; Acute general hospital; Home-visit nurse

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Cancer is the leading cause of death, and over 370,000 cancer patients die in Japan annually [1, 2]. Home-based palliative care improves patients’ quality of life and increases satisfaction [3, 4]. However, for the past several decades, most patients have spent their end of life (EOL) in the hospital despite wishing to die at home due to barriers for patients and their family, including physical, mental, and financial issues. Therefore, the Japanese government promotes home-based palliative care for patients with cancer in order to support them spending their EOL according to their own values under a basic law concerning provisions for cancer patients [5]. Through these efforts, preparations for EOL home care have been developing, and the proportion of cancer patients dying at home gradually increased to 10.4% in 2015 [6].

Our hospital is an acute general community hospital with 30 departments, nine wards, and 419 beds, which include 11 beds for palliative patients. We have a multi-occupational palliative care team (PCT) that includes nurses staffing a home-visit nursing station. We usually ask neighboring home care clinics to provide home-visiting medical care if patients want to spend their EOL at home. However, we sometimes encounter situations in which it is impossible to find appropriate home care clinics due to temporal or geographical restrictions. In such cases patients are forced to visit the hospital just before their death, or postmortem examinations are required at home according to Japanese law, which disrupts an otherwise calm EOL for both patients and their family. To avoid such a cruel situation, we make an effort to consider patients’ final wishes by providing home care ourselves and visiting them at their deathbed at home.

We herein report our experience in cases of EOL home-based care managed by medical staff in an acute general community hospital and discuss the associated problems and potential solutions.

| Case Reports | ▴Top |

We retrospectively reviewed the clinical data of five cancer patients who received EOL home care managed by our institution between May 2016 and October 2018.

We first assessed the background characteristics and clinical course of their EOL care and how medical staff managed the patients. We then analyzed their degree of satisfaction in the EOL care we provided, based on interviews with the patients and their families.

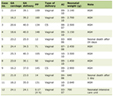

We performed EOL home care for five patients, and medical staff from our institution visited their home when they died. The patient characteristics are outlined in Table 1. The median duration between the first visit to our hospital to death was 164 (range: 24 - 229) days. The background of EOL home care was as follows: two patients in an outpatient setting suffered a rapidly worsening general condition and wished to die at home; two hospitalized patients expressed a sudden desire to be discharged, and we did not have enough time to find home-care doctors; one hospitalized patient suffered a worsening general condition during a transient outing at home.

Click to view | Table 1. Patient Characteristics and Visiting Staff When Patients Died |

The period from the day when patients hoped to be discharged to the day they were actually discharged in the two hospitalized patients was 5 and 6 days. The median duration between the final examination by doctors in the hospital and death was 5 days (range: 7 h - 5 days). Regarding the visits to the four patients other than the one who died during her outing, nurses from the home-visit nursing station visited the patients’ homes every day in three of four patients; and both a care manager and a medical social worker (MSW) tried to evaluate the condition of the remaining patient by visits and phone calls. Information on the patients’ condition at home was given to the attending doctors, nurses and PCT in order to discuss optimal home care. When patients died, attending doctors visited their home in four of five cases, and another doctor who belongs to an attending department visited in the remaining case. A home-visit nurse, a nurse belonging to the PCT and an MSW also visited in all cases. Two and three patients died in the morning and in the afternoon, respectively.

All patients spent their EOL calmly at home, and their families were pleased with their EOL and grateful to the medical staff who supported the patients.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

We supported patients’ EOL by providing home-based medical care through cooperation with multi-occupational staff and successfully met their final wishes to spend their EOL at home calmly. As a result, all patients and their family felt satisfied and expressed feelings of appreciation. To our knowledge, this is the first report showing the feasibility of managing EOL home care in an acute general community hospital.

The point that allowed us to achieve EOL home care was being able to ask nurses from the home-visit nursing station to visit patients, with the nurses promptly making plans for such visits. This was possibility because we usually cooperate with these nurses closely. Based on the detailed information received from these home-visiting nurses, we were able to understand the patients’ condition easily and provide appropriate directions.

However, there are still some hurdles preventing us from performing effective EOL home care by ourselves at an acute general community hospital. First, it is difficult for doctors to visit patients at home freely and frequently because of the extra-work involved. Indeed, if patients live longer than those experienced in our study (e.g. over 1 week), not only visiting nurses but also doctors will need to visit their home according to changes in their condition and symptoms. As a solution, we keep looking for home care doctors even after we start managing EOL home care in patients with a relatively long estimated prognosis. Second, it is not easy for medical staff, especially doctors in the hospital, to visit patients’ home in the daytime just after they die, as we all have daily routines and duties. Furthermore, we are unable to visit their home late at night due to being outside of working hours. We have informed patients and their family that we might not be able to visit their home promptly and they might have to wait for us to visit for a while, especially when patients die at night. Fortunately, we were able to visit patients’ homes within a few hours after their death because they all died during the daytime, although one attending doctor was unable to visit due to being in surgery at the hospital. We should make daily detailed plans about who can visit patients’ homes at their deathbed in advance.

Conclusions

We supported patients’ EOL by managing home-based medical care in cooperation with multi-occupational staff and successfully granted their final wish to spend their EOL at home calmly. We should organize a system for meeting patients’ changing wishes flexibly.

Conflict of Interest

No competing financial interests exist.

| References | ▴Top |

- Minister's Secretariat, Ministry of health, Labor and Welfare. Report on politics regarding cancer [in Japanese]. www.mhlw.go.jp/seisaku/24.html (Last accessed November 21, 2018).

- National Cancer Center Japan, Service of cancer information, Cancer statistics [in Japanese]. https://ganjoho.jp/reg_stat/statistics/stat/summary.html (Last accessed November 21, 2018).

- Peters L, Sellick K. Quality of life of cancer patients receiving inpatient and home-based palliative care. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53(5):524-533.

doi pubmed - Hughes SL, Weaver FM, Giobbie-Hurder A, Manheim L, Henderson W, Kubal JD, Ulasevich A, et al. Effectiveness of team-managed home-based primary care: a randomized multicenter trial. JAMA. 2000;284(22):2877-2885.

doi pubmed - Minister's Secretariat, Ministry of health, Labor and Welfare. The basic plan to promote cancer control programs [in Japanese]. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-10900000-Kenkoukyoku/gan_keikaku02.pdf (Last accessed November 21, 2018).

- Igarashi N, Miyashita M. The state of Japanese palliative care based on data. Japan Hospice Palliative Care Foundation. White- book of hospice and palliative care [in Japanese]. https://www.hospat.org/assets/templates/hospat/pdf/hakusyo_2017/2017_2.pdf (Last accessed November 21, 2018).

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.