| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 10, Number 6, June 2019, pages 183-187

Polyneuritis and Rare Sequelae of Leptospirosis Contracted While on an Urban Clean-Up Mission in Detroit : A Case Report of Weil’s Disease and Literature Review

Nichole Suzzanne Zuccarinia, b, Samaa Lutfia, Thomas Piskorowskia

aDetroit Medical Center Sinai-Grace Hospital, Detroit, MI 48235, USA

bCorresponding Author: Nichole Suzzanne Zuccarini, Detroit Medical Center Sinai-Grace Hospital, Detroit, MI 48235, USA

Manuscript submitted May 26, 2019, accepted June 13, 2019

Short title: Polyneuritis Caused by Leptospirosis

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3320

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Leptospirosis is a common zoonosis, an infectious disease that infects both humans and animals, which is caused by spirochete bacteria from genus Leptospira. Approximately 30% of children in urban Detroit and 16% of adults in Baltimore demonstrated serologic evidence of previous leptospirosis infections. The Detroit study showed correlation between degree of rat infestation and seropositivity rates. This finding suggests rats are major vectors for human leptospirosis in mainland United States. The leptospires from infected animals survive best in fresh water, damp alkaline soil, vegetation, and mud with temperatures higher than 22 °C. Although leptospirosis is a well documented clinical condition, the sequelae of polyneuritis has not yet been reported to our knowledge. The following case is an example of such an occurrence. A 49-year-old Caucasian female presented to the emergency department with flu-like symptoms after volunteering in an urban Detroit neighborhood clean-up project. She admitted to picking up wood from stagnant water without wearing personal protective equipment. The primary differential diagnosis being Weil’s disease from leptospirosis and was proven positive with serologic testing via the Center for Disease Control. A computed tomography (CT) abdomen and pelvis demonstrated lymphadenopathy throughout the abdomen and near the spinal column. She was treated with ceftriaxone and doxycycline for 12 days but developed chronic neuralgia and polyneuritis. Leptospires are known to cause vasculitis. This patient developed polyneuritis either from direct invasion of the nerves from leptospires or compromised blood supply to the nerves. In addition to antibiotics, patients with severe cases of leptospirosis also require supportive therapy and careful management of renal, hepatic, hematologic, and central nervous system complications. If renal failure ensues, early initiation of hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis may reduce mortality. Rapid identification of symptoms and a high clinical suspicion are paramount because early intervention can save their life.

Keywords: Leptospirosis; Polyneuritis; Neuralgia; Weil’s disease

| Introduction | ▴Top |

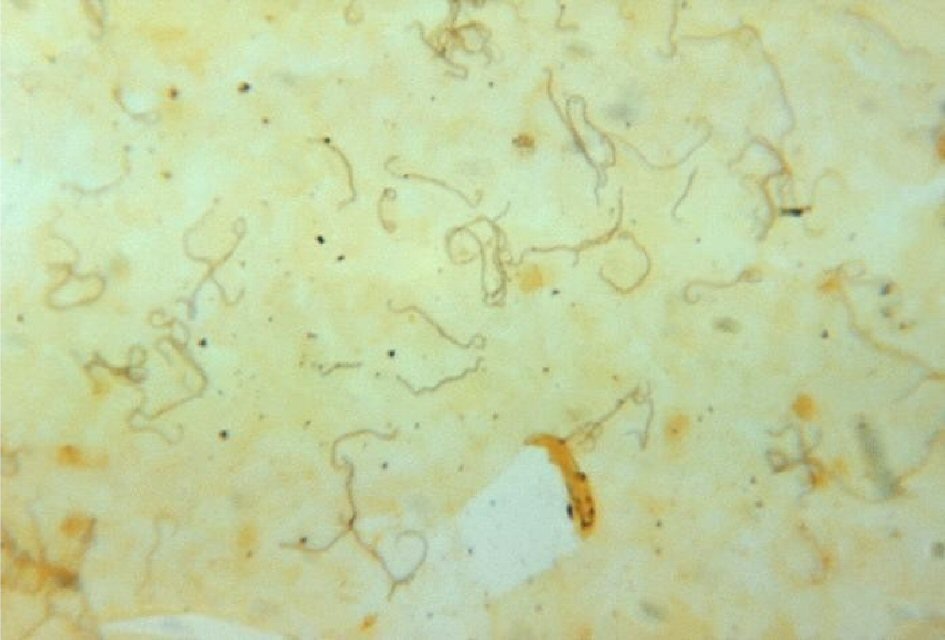

Leptospirosis is a common zoonosis infectious disease that infects both humans and animals, which is caused by spirochete bacteria from genus Leptospira. Leptospires are thin, spiral-shaped Gram-negative aerobic organisms (Fig. 1). They have hooked ends and paired axial flagella allowing them to burrow into tissues. They can be isolated on artificial media, which makes them unique among spirochetes. Its life cycle starts with hematogenous spread of leptospires to the proximal renal tubules where they colonize and shed via urine into the environment. Rats, dogs, and ungulates, among others, that can become chronic, asymptomatic carriers. Humans, however, shed leptospires for a limited time and are accidental hosts. Leptospires are transmitted when mucous membranes, lungs via inhalation or abraded skin is exposed to body fluids of an acutely infected animal and by soil or fresh water contaminated with the urine of a chronic carrier. Seventy percent of leptospirosis cases occur from occupational and recreational exposures. Urban workers and residents in economically deprived areas may contract the disease through exposure to rat urine [1]. Most cases of leptospirosis start with nonspecific signs, like fever, headache, nausea, vomiting. The disease course of leptospirosis falls into two phases: acute phase of illness lasting 5 - 7 days, followed by a 1 - 3 day period of improvement in which the fever and symptoms subside. Leptospirosis can either regress to a relatively asymptomatic illness or progress to a more severe illness. Weil’s disease, also known as icteric leptospirosis, occurs in approximately 10% of cases, and has a fatality rate of 5-10%. Patients with this presentation can have fever, jaundice, renal failure, and hemorrhage. The pulmonary system, cardiac system, and central nervous systems are also frequently involved.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Silver stain of leptospires in fatal human leptospirosis. |

Culture times for Leptospira are long so treatment is begun empirically in patients with a plausible exposure history and compatible symptoms. Serologic identification of leptospires, microscopic agglutination testing (MAT), is available only at reference laboratories. Antibiotic therapy in the treatment of mild leptospirosis is not necessary because the disease is self-limited, and most cases resolve without medical attention. Oral antibiotics shorten the course of illness and urinary excretion of leptospires. Doxycycline is a good first-choice oral antibiotic. For more severe presentations, intravenous penicillin G and third-generation cephalosporins (cefotaxime and ceftriaxone) have shown effectiveness. Severe cases of leptospirosis also require supportive care for renal, hepatic, hematologic, and central nervous system complications. Early initiation of hemodialysis may be needed along with cardiac inotropic medications, eye drops and diuretics. Vasculitis of capillaries, exhibited by endothelial edema, necrosis, and lymphocytic infiltration appears to be the most common presentation. It appears that capillary vasculitis is found in all affected organ systems. The resulting loss of red blood cells and fluid through enlarged junctions and fenestrae, which cause secondary tissue injury, probably accounts for many of the clinical findings [1-54].

Although leptospirosis is a well documented clinical condition, the sequelae of peripheral polyneuritis has not yet been reported to our knowledge. The following case is an example of such an occurrence.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 49-year-old Caucasian female presented to the emergency department with flu-like symptoms after recently volunteering in an urban Detroit neighborhood clean-up project. She admitted to picking up wood from stagnant water without wearing personal protective equipment. She was alert, oriented and able to follow commands on admission. Within hours, she rapidly developed hepatitis, rhabdomyolysis, thrombocytopenia, anemia, acute renal failure requiring hemodialysis, acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, and ultimately, acute respiratory distress syndrome. All initial infectious disease testing was negative. The patient’s history of cleaning up wood from stagnant garbage-filled water was clue to perform zoonotic analyses, with the primary differential diagnosis being Weil’s disease from Leptospirosis. Serologic testing was sent to the Center for Disease Control in Atlanta, which tested positive. She was treated with ceftriaxone and doxycycline for 12 days. Her overall status improved, she was extubated and transferred out of the intensive care unit (ICU). A CT abdomen and pelvis demonstrated lymphadenopathy near the lumbar and sacrum regions of the spinal cord and peripheral nerves. She continued to follow up in the outpatient setting and complained of shock-like pain and neuralgia bilaterally in her lower extremities. The rhabdomyolysis resolved, but her pain remained despite completion of antibiotic treatment which is most likely caused from direct invasion of leptospires into the nerves or compromised blood flow to the nerves. She remains a clinic patient and her pain is controlled with oral medications.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The clinical condition presented above likely was polyneuritis caused by leptospires due to the chronological association seropositivity of leptospirosis, CT evidence of lymphadenopathy near peripheral nerves and spinal cord, persistent neuralgia and polyneuritis symptoms post discharge in the outpatient setting, and lack of an alternative explanation. One could argue that her nerve-type pain was caused from spinal stenosis in the cervical vertebrae, which was seen on subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. However, the patient stated that the pain and shock-like sensations in her lower extremities were new, and started happening immediately after she got leptospirosis. Additionally, cervical spinal stenosis is a chronic, insidious condition and would create neuralgia in both upper and lower extremities. The patient’s pain started from areas seen in the CT where lymphadenopathy was prominent, which were located mainly in the lumbar and sacral regions. Additionally, Leptospirosis is known to cause vasculitis which can cause poor blood flow to the nerves and subsequent damage. This was a plausible theory instead of direct invasion from the leptospires directly into the nerves. However, leptospires may remain in immunologically privileged sites despite being cleared from the blood for months. The only true way to determine the etiology of the patient’s neuralgia would be to biopsy the peripheral nerves, which was not done in this case to date. The patient also suffered from rhabdomyolysis from leptospire invasion which caused pain initially. However, the creatinine kinase level normalized while in the ICU. Plus, the “shock-like” pain the patient complained of after discharge in the clinic is more typical of neuralgia. Regardless of the nerve destruction mechanism, the pain and discomfort felt by the patient is ongoing and knowing the etiology would unlikely change the treatment regimen.

Several recent publications suggested that leptospirosis can lead to meningeal symptoms in 50% of patients. For instance, cranial nerve palsies, encephalitis, peripheral facial palsy and changes in consciousness are less common [2]. Meningitis can last for weeks. Additionally uveitis, iridocyclitis and chorioretinitis can develop and may persist for years. Leptospirosis has also been noted by researchers to be an infective systemic vasculitis [3]. For example, focal necrosis, inflammatory infiltration, and hemorrhage have been documented within the adrenal gland. The main pathologic factor in skin is caused mostly by epithelial vascular insult. Skeletal muscle involvement is secondary to edema, myofibril vacuolization, and vessel damage [1-45]. Although the systemic immune response may eliminate leptospires from the body, a large inflammatory reaction can develop which can produce secondary end-organ injury [1]. Leptospirosis is most prevalent in Hawaii, which consistently reports the highest annual occurrence rate. However, 30% of children in urban Detroit [4] and 16% of adults in Baltimore [5] demonstrated serologic evidence of past infection. The Detroit study also showed correlation between rat infestation levels and seropositivity rates. This finding suggests rats are major vectors for human leptospirosis in the United States. Leptospires from infected animal urine survive best in damp alkaline soil, freshwater, vegetation, and mud with temperatures higher than 22 °C [16].

The woman in this case presented with acute infection, septicemia, and multiorgan failure, followed by rapid immune clearance. She now is stricken with sequelae of polyneuritis and chronic pain. Leptospirosis symptoms are vague and resemble many common viral illnesses. She was started on empiric antibiotic therapy, but she was found to be seropositive for leptospirosis days after her admission and after many immunologic tests. Nonetheless, the turning point for this patient occurred after gaining knowledge from her history of exposure to rat urine during an urban Detroit clean-up project. A high index of suspicion of a zoonotic infection helped save her life. Furthermore, it is essential clinicians are aware that leptospirosis can occur in urban areas, perhaps near a large academic hospital, and be mindful that it often mimics common viral illnesses. There have been no reported cases yet about someone having peripheral neuralgia and polyneuritis from leptospirosis. A peripheral nerve biopsy would help distinguish if this woman had nerve pain from a direct spirochete invasion or vasculitis impeding blood flow to the nerve. But it would not necessarily change her symptomatic treatment, which at this time consists of oral pain medications. It is paramount to educate patients to avoid contact with environments [55] potentially contaminated with animal urine, especially rodent-infested areas and wear protective clothing and shoes. For severe leptospirosis, intravenous penicillin G is considered the drug of choice. But doxycycline and ceftriaxone was used in this case, based on susceptibilities. Supportive care with mechanical ventilation and hemodialysis may also be necessary.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

No financial funding of any kind or monetary contributions were made or accepted.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Verbal consent was obtained from the patient.

Author Contributions

Nichole Zuccarini, lead author of article and physician who worked with patient in clinic; Samaa Lutfi, editor of article; Thomas Piskorowski, attending physician and advisor to clinical case.

| References | ▴Top |

- Silver stain, liver, fatal human leptospirosis. This image is in the public domain and thus free of any copyright restrictions. Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control/Dr. Martin Hicklin).

- Socolovschi C, Angelakis E, Renvoise A, Fournier PE, Marie JL, Davoust B, Stein A, et al. Strikes, flooding, rats, and leptospirosis in Marseille, France. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15(10):e710-715.

doi pubmed - El Bouazzaoui A, Houari N, Arika A, Belhoucine I, Boukatta B, Sbai H, El Alami N, et al. Facial palsy associated with leptospirosis. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2011;128(5):275-277.

doi pubmed - Chakurkar G, Vaideeswar P, Pandit SP, Divate SA. Cardiovascular lesions in leptospirosis: an autopsy study. J Infect. 2008;56(3):197-203.

doi pubmed - Demers RY, Thiermann A, Demers P, Frank R. Exposure to Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae in inner-city and suburban children: a serologic comparison. J Fam Pract. 1983;17(6):1007-1011.

- Childs JE, Schwartz BS, Ksiazek TG, Graham RR, LeDuc JW, Glass GE. Risk factors associated with antibodies to leptospires in inner-city residents of Baltimore: a protective role for cats. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(4):597-599.

doi pubmed - Palaniappan RU, Ramanujam S, Chang YF. Leptospirosis: pathogenesis, immunity, and diagnosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20(3):284-292.

doi pubmed - Asante J, Noreddin A, El Zowalaty ME. Systematic review of important bacterial zoonoses in Africa in the last decade in light of the 'One Health' concept. Pathogens. 2019;8(2):50.

doi pubmed - Yang CW. Leptospirosis in Taiwan - an underestimated infectious disease. Chang Gung Med J. 2007;30(2):109-115.

- Githeko AK, Lindsay SW, Confalonieri UE, Patz JA. Climate change and vector-borne diseases: a regional analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(9):1136-1147.

- National Research Council. Advancing the science of climate change. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010.

- From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: outbreak of acute febrile illness among athletes participating in Eco-Challenge-Sabah 2000 - Borneo, Malaysia, 2000. JAMA. 2001;285(6):728-730.

doi pubmed - Centers for Disease Control, Prevention. Update: leptospirosis and unexplained acute febrile illness among athletes participating in triathlons - Illinois and Wisconsin, 1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47(32):673-676.

- Centers for Disease Control, Prevention. Outbreak of leptospirosis among white-water rafters - Costa Rica, 1996. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997;46(25):577-579.

- Radl C, Muller M, Revilla-Fernandez S, Karner-Zuser S, de Martin A, Schauer U, Karner F, et al. Outbreak of leptospirosis among triathlon participants in Langau, Austria, 2010. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2011;123(23-24):751-755.

doi pubmed - From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of acute febrile illness and pulmonary hemorrhage - Nicaragua, 1995. JAMA. 1995;274(21):1668.

doi - Gaynor K, Katz AR, Park SY, Nakata M, Clark TA, Effler PV. Leptospirosis on Oahu: an outbreak associated with flooding of a university campus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76(5):882-885.

doi pubmed - Levett PN. Leptospirosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14(2):296-326.

doi pubmed - Inada R, Ido Y, Hoki R, Kaneko R, Ito H. The etiology, mode of infection, and specific therapy of Weil's disease (Spirochaetosis Icterohaemorrhagica). J Exp Med. 1916;23(3):377-402.

doi pubmed - Gillespie RW, Ryno J. Epidemiology of leptospirosis. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1963;53:950-955.

doi pubmed - Chierakul W, Tientadakul P, Suputtamongkol Y, Wuthiekanun V, Phimda K, Limpaiboon R, Opartkiattikul N, et al. Activation of the coagulation cascade in patients with leptospirosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(2):254-260.

doi pubmed - Smythe L, Adler B, Hartskeerl RA, Galloway RL, Turenne CY, Levett PN, International Committee on Systematics of Prokaryotes Subcommittee on the Taxonomy of L. Classification of Leptospira genomospecies 1, 3, 4 and 5 as Leptospira alstonii sp. nov., Leptospira vanthielii sp. nov., Leptospira terpstrae sp. nov. and Leptospira yanagawae sp. nov., respectively. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63(Pt 5):1859-1862.

doi pubmed - Centers for Disease Control, Prevention. Summary of notifiable diseases, United States 1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;44(53):1-87.

- Sasaki DM, Pang L, Minette HP, Wakida CK, Fujimoto WJ, Manea SJ, Kunioka R, et al. Active surveillance and risk factors for leptospirosis in Hawaii. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;48(1):35-43.

doi pubmed - Katz AR, Buchholz AE, Hinson K, Park SY, Effler PV. Leptospirosis in Hawaii, USA, 1999-2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(2):221-226.

doi pubmed - Trevejo RT, Rigau-Perez JG, Ashford DA, McClure EM, Jarquin-Gonzalez C, Amador JJ, de los Reyes JO, et al. Epidemic leptospirosis associated with pulmonary hemorrhage-Nicaragua, 1995. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(5):1457-1463.

doi pubmed - Jackson LA, Kaufmann AF, Adams WG, Phelps MB, Andreasen C, Langkop CW, Francis BJ, et al. Outbreak of leptospirosis associated with swimming. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1993;12(1):48-54.

doi pubmed - Dolhnikoff M, Mauad T, Bethlem EP, Carvalho CR. Pathology and pathophysiology of pulmonary manifestations in leptospirosis. Braz J Infect Dis. 2007;11(1):142-148.

doi pubmed - Dall'Antonia M, Sluga G, Whitfield S, Teall A, Wilson P, Krahe D. Leptospirosis pulmonary haemorrhage: a diagnostic challenge. Emerg Med J. 2008;25(1):51-52.

doi pubmed - Hawaii Dept of Health. Communicable disease surveillance. Hawaii: Communicable Disease Report. Nov/Dec 1999. 15.

- Peter G, Narasimha H. Acalculous cholecystitis: a rare presentation of leptospirosis progressing to Weil's disease. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2011;4(12):1007-1008.

doi - Pappachan JM, Mathew S, Thomas B, Renjini K, Scaria CK, Shukla J. The incidence and clinical characteristics of the immune phase eye disease in treated cases of human leptospirosis. Indian J Med Sci. 2007;61(8):441-447.

doi pubmed - Spichler A, Spichler E, Moock M, Vinetz JM, Leake JA. Acute pancreatitis in fatal anicteric leptospirosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76(5):886-887.

doi pubmed - World Health Organization. Human leptospirosis: guidance for diagnosis, surveillance and control. Available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2003/WHO_CDS_CSR_EPH_2002.23.pdf.

- Brett-Major DM, Coldren R. Antibiotics for leptospirosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD008264.

doi pubmed - Costa E, Lopes AA, Sacramento E, Costa YA, Matos ED, Lopes MB, Bina JC. Penicillin at the late stage of leptospirosis: a randomized controlled trial. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2003;45(3):141-145.

doi pubmed - Dursun B, Bostan F, Artac M, Varan HI, Suleymanlar G. Severe pulmonary haemorrhage accompanying hepatorenal failure in fulminant leptospirosis. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(1):164-167.

doi pubmed - Martins MG, Matos KT, da Silva MV, de Abreu MT. Ocular manifestations in the acute phase of leptospirosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 1998;6(2):75-79.

doi pubmed - Takafuji ET, Kirkpatrick JW, Miller RN, Karwacki JJ, Kelley PW, Gray MR, McNeill KM, et al. An efficacy trial of doxycycline chemoprophylaxis against leptospirosis. N Engl J Med. 1984;310(8):497-500.

doi pubmed - Guidugli F, Castro AA, Atallah AN. Antibiotics for preventing leptospirosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;4:CD001305.

doi - CDC. Adventure racing and leptospirosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/leptospirosis/features/adventure-racing.html.

- Harris BM, Blatz PJ, Hinkle MK, McCall S, Beckius ML, Mende K, Robertson JL, et al. In vitro and in vivo activity of first generation cephalosporins against Leptospira. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85(5):905-908.

doi pubmed - Katz AR, Manea SJ, Sasaki DM. Leptospirosis on Kauai: investigation of a common source waterborne outbreak. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(10):1310-1312.

doi pubmed - Khositseth S, Sudjaritjan N, Tananchai P, Ong-ajyuth S, Sitprija V, Thongboonkerd V. Renal magnesium wasting and tubular dysfunction in leptospirosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(3):952-958.

doi pubmed - Lettieri C, Moon J, Hickey P, Gray M, Berg B, Hospenthal D. Prevalence of leptospira antibodies in U.S. Army blood bank donors in Hawaii. Mil Med. 2004;169(9):687-690.

doi pubmed - Phimda K, Hoontrakul S, Suttinont C, Chareonwat S, Losuwanaluk K, Chueasuwanchai S, Chierakul W, et al. Doxycycline versus azithromycin for treatment of leptospirosis and scrub typhus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(9):3259-3263.

doi pubmed - Watt G, Padre LP, Tuazon M, Calubaquib C. Skeletal and cardiac muscle involvement in severe, late leptospirosis. J Infect Dis. 1990;162(1):266-269.

doi pubmed - Jimenez JIS, Marroquin JLH, Richards GA, Amin P. Leptospirosis: Report from the task force on tropical diseases by the World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine. J Crit Care. 2018;43:361-365.

doi pubmed - Delmas B, Jabot J, Chanareille P, Ferdynus C, Allyn J, Allou N, Raffray L, et al. Leptospirosis in ICU: a retrospective study of 134 consecutive admissions. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(1):93-99.

doi pubmed - Mohd Radi MF, Hashim JH, Jaafar MH, Hod R, Ahmad N, Mohammed Nawi A, Baloch GM, et al. Leptospirosis outbreak after the 2014 major flooding event in Kelantan, Malaysia: A spatial-temporal analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98(5):1281-1295.

doi pubmed - de Vries SG, Visser BJ, Stoney RJ, Wagenaar JFP, Bottieau E, Chen LH, Wilder-Smith A, et al. Leptospirosis among returned travelers: A GeoSentinel Site Survey and Multicenter Analysis-1997-2016. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;99(1):127-135.

doi pubmed - Brown VR, Bowen RA, Bosco-Lauth AM. Zoonotic pathogens from feral swine that pose a significant threat to public health. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018;65(3):649-659.

doi pubmed - Kupferman T, Coffee MP, Eckhardt BJ. Case report: a cluster of three leptospirosis cases in a New York city abattoir and an unusual complication in the index case. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97(6):1679-1681.

doi pubmed - CDC. Leptospirosis - prevention in pets. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/leptospirosis/pets/prevention/index.html. June 9, 2015.

- CDC. Hurricanes, floods and leptospirosis. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/leptospirosis/exposure/hurricanes-leptospirosis.html. October 30, 2017.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.