| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 10, Number 6, June 2019, pages 179-182

Hemorrhagic Cystitis With Low-Dose Cyclophosphamide Therapy for Breast Cancer: A Rare Occurrence

Prashanth Ashok Kumara, c, Shweta Paulraja, Abirami Sivapiragasamb

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY, USA

bDepartment of Hematology, Oncology, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY, USA

cCorresponding Author: Prashanth Ashok Kumar, 60 Presidential Plz, Apartment 1407, Syracuse, NY 13202, USA

Manuscript submitted June 4, 2019, accepted June 14, 2019

Short title: Hemorrhagic Cystitis in Low-Dose Cyclophosphamide

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3321

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Cyclophosphamide (CP) is known to cause hemorrhagic cystitis (HC), and this adverse effect is more commonly seen in patients receiving high individual doses used in the treatment of sarcomas and conditioning regimens during hematopoietic cell transplant. There are a few reported cases of HC in doses used for breast cancer. We report the case of a 63-year-old lady with stage IIA breast cancer who was started on adjuvant CP and docetaxel therapy at a dose of 600 mg/m2 and 75 mg/m2 respectively. She developed gross hematuria in less than 24 h after her first cycle and was found to have evidence suggestive of HC on cystoscopy done subsequently. She went on to complete three more cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy with CP and docetaxel with concurrent mesna and hydration. She did not develop any further episodes of hematuria. We review the literature pertaining to our case, and also compare the characteristics of the patient in our case with previously described cases of breast cancer who developed HC with low-dose CP.

Keywords: Breast cancer; Hemorrhagic cystitis; Low-dose cyclophosphamide; Mesna

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Cyclophosphamide (CP) is a DNA alkylating agent, and is an important agent in the management of several pediatric and adult malignancies, rheumatological conditions and vasculitis [1]. With regard to breast cancer, it is one of the most widely used chemotherapeutic agents, and is a part of several combination chemotherapeutic regimens [2, 3]. Hemorrhagic cystitis (HC) can be caused by several chemotherapeutic agents, but common clinical encounters have been reported with CP and ifosfamide [4]. HC with CP is usually noted either with high individual doses as used for myeloablative stem cell transplant conditioning or large cumulative doses over a prolonged duration as in rheumatological disorders like lupus nephritis and granulomatosis with polyangitis [5, 6]. Rare cases of HC following smaller doses as used in breast cancer have also been reported [7]. We report a rare case of HC following a single dose of CP used for adjuvant therapy of breast cancer and its successful management and prevention with mesna and hydration.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 63-year-old woman presented to the hospital with gross hematuria. She had a past medical history of prediabetes, a hysterectomy secondary to an endometrial infection and recently diagnosed breast cancer. A hypoechoic lesion was identified on routine mammogram in the left upper outer quadrant of her breast. Thereafter, she underwent a left breast ultrasound-guided biopsy of this hypoechoic lesion, which was located at the 2 o’clock position, 5 cm from the nipple. It was around 11 mm in size at that time. Pathology was positive for invasive ductal carcinoma, grade 2, estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) positive. She then underwent an magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the bilateral breasts which revealed a 2.5 cm left breast mass at the 2 o’clock position with no lymphadenopathy. Scattered T2 hyperintensities were seen, which were compatible with cysts. One month later she underwent a left breast lumpectomy with a left axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy. Pathology revealed a 1.7 × 1.3 × 1.1 cm invasive ductal carcinoma with focal ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) findings and focal ductal hyperplasia. Tumor was grade 2 with presumed lymphovascular invasion. ER positive 100%, PR positive 100%, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) equivocal. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) came back negative. The left axillary sentinel lymph node was positive for a 3.5 mm focus of adenocarcinoma.

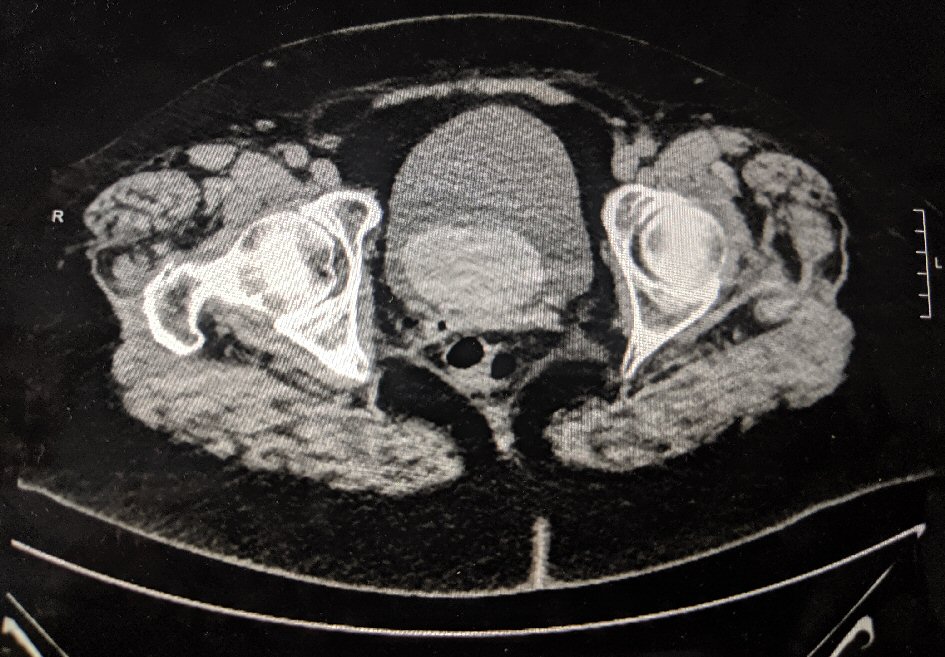

The decision was made to initiate her on adjuvant CP and docetaxel therapy. She received her first dose of CP regimen at a dose of 600 mg/m2 in 250 mL normal saline (NS) along with docetaxel at 75 mg/m2 in 250 mL NS. She then developed gross hematuria in less than 24 h after her first cycle. She presented to the emergency department (ED) with complaints of gross hematuria, increased urinary frequency and urgency with micturition. It was associated with difficulty in passing urine, abdominal cramps and suprapubic pain. She did not have any other constitutional symptoms. She was not on any antiplatelets or anticoagulants. Initial laboratory workup in the ED showed no markers for a coagulopathy, and urinalysis was not suggestive of a urinary tract infection (UTI). As the patient continued to complain of a feeling of urinary retention, she had a bladder scan done with a volume of 650 mL in her bladder. A Foley catheter was placed in the ED with some relief in her discomfort. She had a non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan which revealed a mass in the urinary bladder likely a hematoma versus a bladder mass (Fig. 1). Irrigation was attempted without much success and Foley was upsized with evacuation of several clots after bladder infusions. The patient’s oncologist was consulted and suspicion for HC was low at this point. A repeat ultrasound was done which did not show the echogenic mass.

Click for large image | Figure 1. CT abdomen and pelvis demonstrating a possible hematoma in the bladder. |

Patient was then given a voiding trial and she voided without any difficulty. She was scheduled for a follow-up with urology for a cystoscopy after discharge. The cystoscopy revealed an erythematous inflammatory lesion of 6 mm on the left ureteral orifice over the posterior wall. No calculi were visualized. Part of the flat erythematous patch was biopsied and the entire area was treated with fulguration. Pathology of the biopsied tissue showed some disorganization and a rare papillary fragment, suggestive of HC.

For the subsequent cycle, the patient received her infusion with mesna 120 mg/m2 before CP, 4 h and 8 h after. She was also given continuous intravenous (IV) NS at the rate of 125 mL/h for a total of 3.5 L to flush the acrolein from her system. She was given additional oral mesna 200 mg on an outpatient basis. She did not have a recurrence of HC after cycle two. She subsequently received two further cycles of CP with docetaxel with a similar regimen of mesna. She has had no further episodes of hematuria since then. She subsequently received adjuvant radiation therapy for her breast cancer as well.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

We report a case of HC in a patient with breast cancer on low-dose CP therapy. It is a very uncommon occurrence with only three cases reported in literature so far. HC is a potentially morbid inflammatory bleeding of the bladder mucosa that can occur due to various etiologies like bacterial infection, viruses like polyomavirus, toxins like aniline dyes, radiation and exposure to drugs like CP, ifosfamide, danazol, busulphan and allopurinol [8]. The incidence of HC following high-dose CP is around 30%, with literature showing a range of 12-41% [8, 9]. CP is used in the treatment of various rheumatological conditions like granulomatosis with polyangitis, microscopic polyangiitis, lupus nephritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Although the dose used in these conditions are much smaller (1.5 to 2 mg/kg/day orally or 500 - 1,000 mg/m2 as monthly or biweekly pulsed regime) than that used in the treatment of malignancies (600 - 1,000 mg/m2 as weekly or biweekly regimes), the drug is given over a prolonged period of time resulting in larger cumulative doses [7, 8]. Among patients with confirmed HC, the mean dosage of CP was 100 g over a period of 30 months [8].

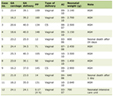

Although rare, a few cases of HC in cancer patients have been described. Marshall et al, describes a patient who experienced HC following a single 600 mg/m2 dose of CP along with docetaxel used for breast cancer. It was subsequently prevented with mesna and hydration (Table 1, case 2) [7]. This was very similar in presentation to our case. Wong et al illustrates a case of severe HC in ovarian cancer after a single 600 mg/m2 dose [10]. Tanaka et al reported two cases of HC in breast cancer patients following cumulative dosage of 60.8 and 74.8 g of CP (Table 1, cases 3 and 4) [11].

Click to view | Table 1. Comparison of Baseline Patient Characteristics in Reported Cases of Low-Dose CP and HC in Breast Cancer |

CP undergoes hepatic microsomal breakdown to hydroxycyclophosphamide, then to aldophosphamide which is eventually broken down into phosphoramide mustard and acrolein. While phosphoramide mustard is the active antineoplastic metabolite, acrolein has no particular therapeutic activity [12]. Acrolein is toxic to the entire urinary tract, but the bladder is the most effected as it is exposed to the metabolite the longest [13]. Acrolein acts as a proinflammatory irritant that activates tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 1 beta and endogenous nitric oxide (NO) [14]. All of this in a dose and time dependent manner causes necrosis, sloughing, ulceration, leucocytic infiltration and eventually hemorrhage of the bladder wall mucosa. It also causes increase in plasma protein extravasation and wet weight of the bladder [15]. CP is a drug that undergoes complex metabolic changes in the body involving cytochrome P450, glutathione S transferase and aldehyde dehydrogenase enzymes. Polymorphisms in these enzymes may affect toxicity and clinical outcomes [16]. CP is also associated with bladder wall fibrosis and an increased risk of urothelial cancer. In a study done in Wegener’s granulomatosis patients treated with CP, the incidence of bladder cancer was around 5% [13].

The drug sodium 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate, also known as mesna has been used in the prevention of HC caused by both ifosfamide and CP [17]. Mesna can be administered as both IV and oral forms. The sulfhydryl groups of mesna bind with the urotoxic elements of acrolein and prevent it from acting on the bladder wall [4, 18]. The efficacy of mesna, especially in CP patients is controversial and HC still occurs in 10-40% of mesna-treated patients [19]. Liberal hydration before and several hours after administration of CP is recommended to prevent HC [4]. In 1991, Shepard et al conducted a randomized control trial with 100 patients and showed that hyper-hydration is non-inferior to mesna in preventing HC. Some authors have also opined that hyper-hydration is more safe and cost effective than mesna [20, 21]. A single institutional study was done by Saito Y et al who showed that patients receiving low and intermediate doses of CP (< 1,500 mg/m2/day) would benefit from > 125 mL/h of fluids to prevent HC, and those getting high dose CP (> 1,500 mg/m2/day) should receive both mesna and vigorous hydration to prevent HC [22]. Majority of the evidence on the role of mesna in preventing CP-induced HC has been in rheumatological disorders, and even in the same, most of the data have been extrapolated from ifosfamide in cancer patients and from animal models. Thus the role of mesna even in rheumatological conditions where it has been extensively studied is uncertain, which thus entails more research in this area [4]. The data are even scarce with regard to its use in cancer patients as only a few case reports have been published [7, 10, 11]. Regardless, our experience and that of Marshall et al [7] support the fact that the use of mesna has been effective. Recently, a number of reports have shown that hyperbaric oxygen therapy may be effective in treating HC, even in those patients who are refractory to other modalities [23, 24]. But large scale trials are lacking and are needed to establish the same results.

Our experience, similar to that of Marshall et al [7], has shown that in HC caused by CP used in doses to treat breast cancer, mesna and hydration have been effective to prevent recurrence. More case reports and clinical trials are needed to establish standard guidelines to treat HC especially in cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

Sincerest thanks to Division of Hematology-Oncology, Upstate University Hospital and Department of Medicine, Upstate University Hospital for the support.

Financial Disclosure

The case report was supported by the Department of Hematology Oncology, Upstate Medical University.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Prashanth Ashok Kumar: preparation and writing of manuscript, editing of manuscript, case analysis; Shweta Paulraj: preparation and writing of manuscript, editing of manuscript; Abirami Sivapiragasam: guide and mentor, editing of manuscript, patient care and management.

| References | ▴Top |

- Pinto N, Ludeman SM, Dolan ME. Drug focus: Pharmacogenetic studies related to cyclophosphamide-based therapy. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10(12):1897-1903.

doi pubmed - Stoll BA. Evaluation of cyclophosphamide dosage schedules in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1970;24(3):475-483.

doi pubmed - Hung CM, Hsu YC, Chen TY, Chang CC, Lee MJ. Cyclophosphamide promotes breast cancer cell migration through CXCR4 and matrix metalloproteinases. Cell Biol Int. 2017;41(3):345-352.

doi pubmed - Efros MD, Ahmed T, Coombe N, Choudhury MS. Urologic complications of high-dose chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. Urology. 1994;43(3):355-360.

doi - Monach PA, Arnold LM, Merkel PA. Incidence and prevention of bladder toxicity from cyclophosphamide in the treatment of rheumatic diseases: a data-driven review. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(1):9-21.

doi pubmed - Lunde LE, Dasaraju S, Cao Q, Cohn CS, Reding M, Bejanyan N, Trottier B, et al. Hemorrhagic cystitis after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: risk factors, graft source and survival. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50(11):1432-1437.

doi pubmed - Marshall A, McGrath C, Torigian D, Papanicolaou N, Lal P, Kaplan Tweed C. Low-dose cyclophosphamide associated with hemorrhagic cystitis in a breast cancer patient. Breast J. 2012;18(3):272-275.

doi pubmed - Manikandan R, Kumar S, Dorairajan LN. Hemorrhagic cystitis: A challenge to the urologist. Indian J Urol. 2010;26(2):159-166.

doi pubmed - Varma PP, Subba DB, Madhoosudanan P. CYCLOPHOSPHAMIDE INDUCED HAEMORRHAGIC CYSTITIS (A Case Report). Med J Armed Forces India. 1998;54(1):59-60.

doi - Wong TM, Yeo W, Chan LW, Mok TS. Hemorrhagic pyelitis, ureteritis, and cystitis secondary to cyclophosphamide: case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;76(2):223-225.

doi pubmed - Tanaka T, Nakashima Y, Sasaki H, Masaki M, Mogi A, Tamura K, Takamatsu Y. Severe hemorrhagic cystitis caused by cyclophosphamide and capecitabine therapy in breast cancer patients: two case reports and literature review. Case Rep Oncol. 2019;12(1):69-75.

doi pubmed - Schoenike SE, Dana WJ. Ifosfamide and mesna. Clin Pharm. 1990;9:179-191.

- Talar-Williams C, Hijazi YM, Walther MM, Linehan WM, Hallahan CW, Lubensky I, Kerr GS, et al. Cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis and bladder cancer in patients with Wegener granulomatosis. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124(5):477-484.

doi pubmed - Ribeiro RA, Freitas HC, Campos MC, Santos CC, Figueiredo FC, Brito GA, Cunha FQ. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1beta mediate the production of nitric oxide involved in the pathogenesis of ifosfamide induced hemorrhagic cystitis in mice. J Urol. 2002;167(5):2229-2234.

doi - Souza-Fiho MV, Lima MV, Pompeu MM, Ballejo G, Cunha FQ, Ribeiro Rde A. Involvement of nitric oxide in the pathogenesis of cyclophosphamide-induced hemorrhagic cystitis. Am J Pathol. 1997;150(1):247-256.

- Liang L, Chen D, Wang X, Yang Z, Zhou J, Zhan Z, Lian F. Rare Cyclophosphamide-Induced Hemorrhagic Cystitis in a Chinese Population with Rheumatic Diseases. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2017;4(3):175-182.

doi pubmed - Haselberger MB, Schwinghammer TL. Efficacy of mesna for prevention of hemorrhagic cystitis after high-dose cyclophosphamide therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 1995;29(9):918-921.

doi pubmed - Dorr RT. Chemoprotectants for cancer chemotherapy. Semin Oncol. 1991;18(1 Suppl 2):48-58.

- Ali SA, Danda SK, Basha SA, Rasheed A, Ahmed O, Ahmed MM. Comparision of uroprotective activity of reduced glutathione with mesna in ifosfamide induced hemorrhagic cystitis in rats. Indian J Pharmacol. 2014;46(1):105-108.

doi pubmed - Shepherd JD, Pringle LE, Barnett MJ, Klingemann HG, Reece DE, Phillips GL. Mesna versus hyperhydration for the prevention of cyclophosphamide-induced hemorrhagic cystitis in bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9(11):2016-2020.

doi pubmed - Matz EL, Hsieh MH. Review of Advances in Uroprotective Agents for Cyclophosphamide- and Ifosfamide-induced Hemorrhagic Cystitis. Urology. 2017;100:16-19.

doi pubmed - Saito Y, Kumamoto T, Shiraiwa M, Sonoda T, Arakawa A, Hashimoto H, Tamai I, et al. Cyclophosphamide-induced hemorrhagic cystitis in young patients with solid tumors: A single institution study. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2018;14(5):e460-e464.

doi pubmed - Kaur D, Khan SP, Rodriguez V, Arndt C, Claus P. Hyperbaric oxygen as a treatment modality in cyclophosphamide-induced hemorrhagic cystitis. Pediatr Transplant. 2018;22(4):e13171.

doi pubmed - Jou YC, Lien FC, Cheng MC, Shen CH, Lin CT, Chen PC. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for cyclophosphamide-induced intractable refractory hemorrhagic cystitis in a systemic lupus erythematosus patient. J Chin Med Assoc. 2008;71(4):218-220.

doi

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.