| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 11, Number 7, July 2020, pages 224-227

Diagnosing Lyme Carditis Presenting With Complete Heart Block

Padmaraj Samarendraa, c, Saloni Kapoorb

aDivision of Cardiology, VA Medical Center, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

bDivision of Internal Medicine, VA Medical Center, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

cCorresponding Author: Padmaraj Samarendra, Division of Cardiology, VA Medical Center, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Manuscript submitted June 12, 2020, accepted June 20, 2020, published online June 29, 2020

Short title: Diagnosing Lyme Carditis Presenting With CHB

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3529

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Diagnosing self-limited conduction abnormality of Lyme carditis in absence of pathognomonic skin rash or history of tick bite is challenging but necessary to avoid placement of pacemaker particularly in young patients. High degree of clinical suspicion, rapidly progressing conduction block and prompt response to antibiotics may help in diagnosis.

Keywords: Lyme carditis; Complete heart block; Lyme disease; Conduction abnormality

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Lyme disease is an uncommon cause of carditis, which manifests most often with conduction abnormalities. Lyme carditis presenting with an isolated complete heart block (CHB), without characteristic skin lesion, constitutional symptoms and other manifestations of the disease, is difficult to diagnose. Diagnosis becomes even more difficult in absence of a history of tick bite in a patient with risk factors for other causes of heart block such as coronary artery disease, degenerative disease or infiltrative myocardial diseases.

Recognition, however, is critical because heart block due to Lyme carditis is mostly reversible [1, 2] and a correct diagnosis avoids the need for permanent pacemaker placement and the long-term complications that come with it.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

We present the case of a man, presenting with first-degree heart block, which progressed to CHB within hours and resolved promptly after receiving antibiotic to treat Lyme disease.

A 66-year-old man without prior cardiovascular issues presented in the first week of August with generalized body ache. The clinical examinations including skin examination and routine blood investigation were unremarkable then. An electrocardigram (ECG) had shown sinus rhythm, normal PR interval and a pre-existing right bundle branch block (RBBB).

He returned in early September complaining of light headedness, dizziness and breathlessness upon exertion for 6 - 7 days. A week earlier he had complained of fatigue and feeling unwell.

He was a Pittsburgh (USA) native, with schizophrenia and depression but no hypertension or diabetes. He was not on any medication causing heart block. The clinical examination at this time showed a regular pulse of 89 beats/min and blood pressure (BP) 134/92 mm Hg, temperature 36.6 °C (98.0 °F) and respiratory rate 18/min with O2 saturation of 94% on room air. The cardiac, pulmonary, neurological and abdominal examinations were unremarkable. No skin lesion or joint abnormality was present, except for trace ankle edema bilaterally.

A chest X-ray and routine blood investigations that included troponin-I were within normal limits, although erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 53 and C-reactive protein (CRP) 3 were elevated. Drug screen was unremarkable.

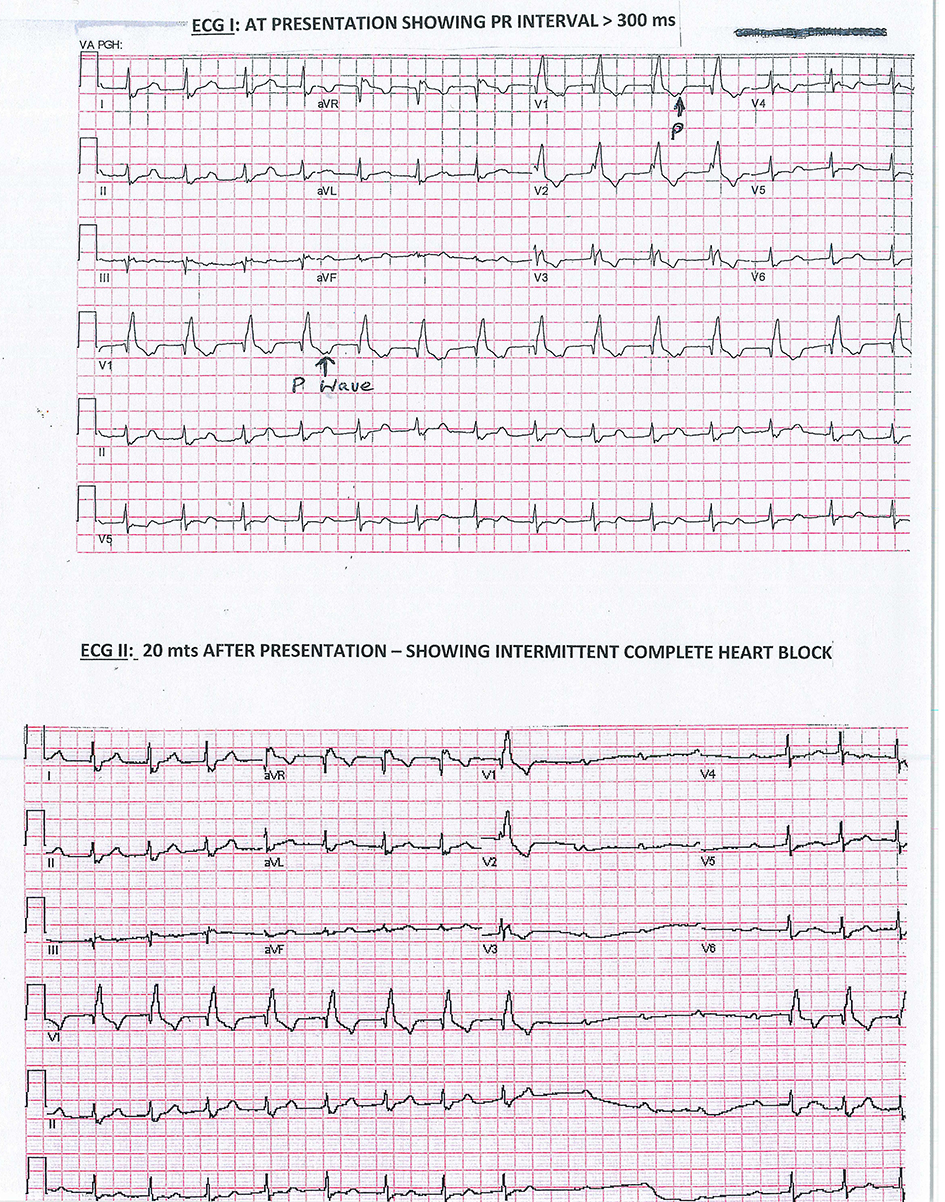

An initial ECG showed a new prolongation of PR interval to 320 ms with pre-existing RBBB. An ECG repeated due to non-conducted P waves seen on monitor showed several non-conducted P waves, without evidence of acute ischemic injury, which progressed to a CHB, with idioventricular rhythm at 32 bpm, and persistent RBBB in minutes on subsequent ECGs (Fig. 1). An echocardiogram showed normal valvular and systolic functions.

Click for large image | Figure 1. ECG I: At presentation showing PR interval > 300 ms; ECG II: 20 min after presentation showing intermittent complete heart block. ECG: electrocardiogram. |

Further questioning in view of rapidly progressing heart block in absence of sign symptoms of acute myocardial or systemic disease revealed that the patient had been bitten by a tick in late May while walking his dog “in woods”. However, he never noticed any skin lesion.

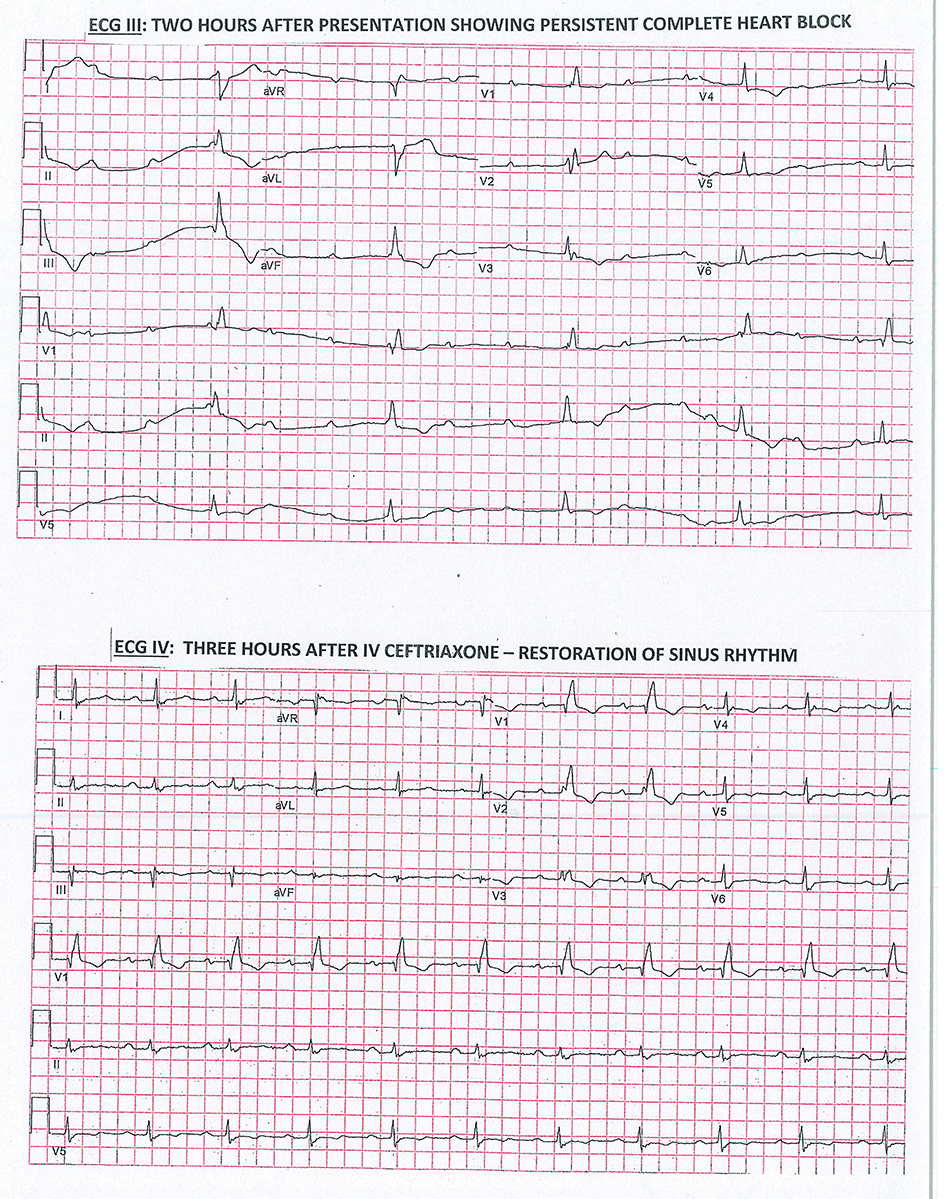

Considering the possibility of Lyme carditis, 2 g of ceftriaxone was given intravenously, and pacemaker placement was deferred as the patient remained hemodynamically stable. Approximately 3 h after the antibiotic, sinus rhythm was restored, and PR shortened to 230 ms (Fig. 2). Later patient’s Lyme serology with Western blot yielded a positive result for both immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin M (IgM) along with Borrelia specific band.

Click for large image | Figure 2. ECG III: Two hours after presentation showing persistent complete heart block. ECG IV: Three hours after IV ceftriaxone-restoration of sinus rhythm. ECG: electrocardiogram; IV: intravenous. |

Patient was treated with intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone for 3 days and then discharged on oral doxycyclin 100 mg twice a day for a total of 21 days of treatment. Two week of cardiac monitoring following discharge showed progressively decreasing PR interval, but persistent first-degree heart block without any arrhythmia. The ECG returned to the baseline with pre-existing RBBB and normal PR interval in approximately 6 weeks.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Lyme disease caused by Borrelia species is a systemic disease. The median age of infected patients in USA has a bimodal distribution with peaks at 5 - 9 years and 44 - 59 years [3]. Heart is involved in 4-10% patients during early disseminated phase of the disease [2]. Although involvement of all cardiac structure is possible, valvular affection is rare; a supra-Hissian atrial-ventricular (A-V) nodal involvement is most common and there are varying degrees of conduction blocks, the most common presenting feature. Additionally, pericarditis, diffuse myocarditis, coronary artery aneurysm, small vessel vasculitis, and even sudden cardiac deaths have been rarely reported [3, 4]. Myocardial involvement and presentation with congestive heart failure have been reported in 10-15% patients with Lyme carditis [2, 5]; however, in most cases left ventricular dysfunction is mild and self-limiting [6, 7].

Immunological reaction to direct invasion of cardiac tissues by the spirochete evokes inflammatory response. On histopathology, a linear perivascular and interstitial lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in a “roadmap” or “band like” pattern often involving all cardiac layers is seen [3].

Cardiac manifestations appear from weeks to months after onset of infection, typically occurring between June and December which correlates with a delay from infection to presentation, as the nymph from vector Ixodes generally arises in May and June. Lyme carditis is three times more common in men. Common complains of cardiac involvement include light-headedness, palpitation, syncope, dyspnea and chest pain [3]. In a review of 84 Lyme carditis patients by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), most common complaint was palpitation (69%) while only 5% had signs and symptoms of left ventricular dysfunction [8].

Cardiac manifestations of early disseminated Lyme disease usually accompany other clinical features of the disease. The first case series reported the presence of erythema migrans (75%), joint involvement (65%), and neurological symptoms (35%) in patient presenting with Lyme carditis [5].

Another case series reported erythema migrans in 67%, joint complains in 51% and early neurological manifestations in 27%. Electrophysiological studies of patients showed diffuse conduction system involvement with prolonged A-H and H-V intervals. Intra-atrial conduction time was prolonged also. There was lack of response to atropine in most patients, perhaps indicating direct inflammatory involvement of the A-V node, rather than a vagotonic effect, as the cause of the block. Temporary pacing was required in only 35% patients in this series [6].

The presentation of Lyme disease solely with a CHB, where patient could not recollect a tick bite, has been reported earlier [9]. Diagnosis is implicated by rapid progression of the conduction abnormality to a higher degree block in minutes to hours, when initial ECG shows PR interval > 300 ms [5].

Rapidly progressive conduction abnormality, apart from an acute ischemic event, may also occur in acute myocarditis, such as giant cell or rheumatic carditis with symptoms of myocardial ischemia or diffuse involvement of myocardium, causing heart failure predominates the clinical presentation. Atrioventricular block as a presenting manifestation has also been reported with cardiac sarcoidosis, a granulomatous inflammatory myocarditis and giant cell myocarditis. Another tick-born disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever commonly causes conduction abnormality but again symptoms of fulminant heart failure from extensive myocardial involvement usually are the presenting feature.

Isolated CHB without overt symptoms of heart failure in Lyme carditis can be explained by the pattern of pathology seen in mice with experimental Lyme carditis [10] and is also reported in autopsies [2]. The inflammation involved the connective tissues at the base of the heart and basal interventricular septum, close to A-V node most severely, while involvement of the myocardium was only mild. A focal myocarditis in the atrioventricular region seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with late gadolinium enhancement in acute Lyme carditis was also reported [11].

Peeters et al, at 1990 International Conference on Lyme Borreliosis in Sweden [12], suggested that Lyme carditis may be an unrecognized and hidden cause of CHB, based on their finding of anti-burgdorferi antibody in pacemaker-treated patients compared to controls. Seropositive patients also showed more resolution of their heart block on treatment with antibiotics to treat Lyme disease.

Reinfection of Lyme disease has been well documented, even after successful treatment clinically. Reinfection may be related to repeated tick bite, incomplete protective immune response, strain variability of Borrelia species or recrudescence [13].

Evidence for Lyme infection in a patient presenting with heart block should be sought, routinely, particularly in endemic areas, and during summer months. Diagnosis should be strongly suspected in case of a rapid fluctuation and progression of atrioventricular block, without clinical evidence of myocardial disease.

The case presents opportunity to construct a differential diagnosis for causes of rapidly progressive conduction abnormality and heart block particularly in a young patient. It exemplifies the ECG features of the conduction block caused by Lyme carditis also along with its characteristic of rapid progression and resolution with appropriate antibiotic.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

The written informed consent has been provided.

Author Contributions

Both authors have contributed equally in patient’s care, literature search and preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Forrester JD, Mead P. Third-degree heart block associated with lyme carditis: review of published cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(7):996-1000.

doi pubmed - McAlister HF, Klementowicz PT, Andrews C, Fisher JD, Feld M, Furman S. Lyme carditis: an important cause of reversible heart block. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110(5):339-345.

doi pubmed - Fish AE, Pride YB, Pinto DS. Lyme carditis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2008;22(2):275-288, vi.

doi pubmed - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Three sudden cardiac deaths associated with Lyme carditis - United States, November 2012-July 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(49):993-996.

pubmed - van der Linde MR. Lyme carditis: clinical characteristics of 105 cases. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1991;77:81-84.

- Steere AC, Batsford WP, Weinberg M, Alexander J, Berger HJ, Wolfson S, Malawista SE. Lyme carditis: cardiac abnormalities of Lyme disease. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93(1):8-16.

doi pubmed - Horowitz HW, Belkin RN. Acute myopericarditis resulting from Lyme disease. Am Heart J. 1995;130(1):176-178.

doi - Ciesielski CA, Markowitz LE, Horsley R, Hightower AW, Russell H, Broome CV. Lyme disease surveillance in the United States, 1983-1986. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(Suppl 6):S1435-1441.

doi - Kimball SA, Janson PA, LaRaia PJ. Complete heart block as the sole presentation of Lyme disease. Arch Intern Med. 1989;110(5):339-345.

- Saba S, VanderBrink BA, Perides G, Glickstein LJ, Link MS, Homoud MK, Bronson RT, et al. Cardiac conduction abnormalities in a mouse model of Lyme borreliosis. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2001;5(2):137-143.

doi pubmed - Naik M, Kim D, O'Brien F, Axel L, Srichai MB. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Lyme carditis. Circulation. 2008;118(18):1881-1884.

doi pubmed - Presentation–Lyme Borreliosis: a hidden cause of heart block in Pacemaker treated males. Presented at IV International Conference on Lyme borreliosis. Stockholm, Sweden 1990.

doi pubmed - Nadelman RB, Wormser GP. Reinfection in patients with Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(8):1032-1038.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.