| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 11, Number 11, November 2020, pages 358-361

Prolonged Positive COVID-19 Test in Recovered Patient

Christine X.Q. Phama, Michelle Uttaburanonta, b, d, Maciej Witkosc

aRancho Family Medical Group, Temecula, CA 92592, USA

bUniversity of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA

cDepartment of Emergency Medicine, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, CA 92354, USA

dCorresponding Author: Michelle Uttaburanont, Rancho Family Medical Group, 31150 Temecula Parkway Suite 200, Temecula, CA 92592, USA

Manuscript submitted August 25, 2020, accepted September 4, 2020, published online September 23, 2020

Short title: Prolonged Positive COVID-19 Test in Patient

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3572

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is a global pandemic that has affected millions worldwide since its initial outbreak in Wuhan, China in December 2019. Discussion of atypical cases of COVID-19 is essential to gaining insight into the clinical presentations of this infection. The authors report a case in which a 74-year-old female who sought medical evaluation via telemedicine for chief complaints of recurrent low-grade fever, dyspnea, dry cough, and myalgias and subsequently tested positive for the SARS-CoV-2 multiple times in over 7 weeks despite prior resolution of symptoms. The patient’s 78-year-old husband who resides in the same household also contracted the SARS-CoV-2.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19; RT-PCR; Pandemic; Self-quarantine; Antibody; Transmissibility; Telemedicine

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Nearly 9 months since the initial outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports 6.0 million cases of infection in the USA with over 184,000 deaths and counting. A majority of these cases present with mild symptoms and appear to recover in approximately 2 weeks on average. However, a previous report has been made of two patients who had coexisting severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and virus-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM for up to 50 days [1].

At this time, details regarding duration of household transmission, viral shedding, and period of infectiousness remain unclear. A retrospective case series on household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 revealed a 30% rate of transmission among those who received reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays [2]. Findings of a recent study suggest the transmissivity of the novel coronavirus is significantly decreased among patients who retest positive after recovery from COVID-19 [3]. Several studies on IgG and IgM antibody responses in COVID-19 patients and SARS-CoV-2 viral shedding have been performed [4-8], but further information is crucial to better understand the epidemiological characteristics of this virus. In the present report, we describe a patient with mild clinical manifestations of COVID-19 who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 for 53 days based on RT-PCR on nasopharyngeal swab, as well as her husband who also tested positive for the virus but had a shorter positive period despite a more moderate presentation of symptoms.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 74-year-old female with a history of hyperlipidemia, impaired fasting glucose, bronchitis, and anxiety presented herself to the emergency department for complaints of fever and shortness of breath. She reported a gradual onset of recurrent low-grade fevers of temperatures up to 37.9 °C, dyspnea, dry cough, sore throat, sinus congestion, myalgias, and diarrhea 12 days prior to presentation to the emergency department. These symptoms had progressively worsened in the few days prior and the patient reported minimal relief with supportive therapy at home. The patient was previously evaluated twice via Telemedicine by an urgent care provider as well as her primary care physician (PCP) who prescribed azithromycin and an albuterol inhaler. Prior to the onset of acute respiratory symptoms, the patient had no recent domestic or international travels, however an asymptomatic family member did visit from out-of-state the past week. The patient denied any known exposure to positive or suspected COVID-19 cases. She lives with her husband and maintained strict adherence to safer-at-home recommendations. She and her husband went to the grocery store once, but otherwise denied any contact to any other individuals.

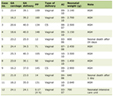

Upon arrival the patient was alert, oriented, and could speak in complete sentences with no audible shortness of breath or wheezing. She was afebrile at 36.9 °C and not hypoxic with oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 93% on room air. The patient exhibited clear breath sounds bilaterally on auscultation with no tachypnea, no wheezing, no rales, and no rhonchi. Labs revealed mild leukocytosis at 11.3 × 103/µL but were otherwise unremarkable. Swabs for influenza A and B antigens (Ags) were both negative. Initial imaging via chest X-ray revealed clear lung fields without infiltrate or pleural effusion. Results of the SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR nasopharyngeal swab were positive. Over the course of the next several weeks, the patient was managed as outpatient through regular monitoring via telemedicine. On day 51 the results of her antibody testing returned positive for both SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG and IgM antibodies. The patient continued to test positive for the SARS-CoV-2 64 days after the initial onset of symptoms despite the near resolution of her symptoms by day 25 (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Laboratory Results for Patient A and Her Husband |

In comparison, the patient’s husband, a 78-year-old male with a history of hypertension and one cardiac stent, presented himself to the emergency department on the same day as his wife with complaints of flu-like symptoms. He reported a gradual onset of rhinorrhea, generalized weakness, myalgias, cough, fever up to 38.1 °C, chills, and diarrhea 12 days prior to presentation to the emergency department. Upon arrival, the patient was also alert and oriented with no evidence of respiratory distress. At the time of evaluation, the patient was afebrile at 36.7 °C and exhibited good oxygenation with SpO2 of 98% on room air. Like his wife, the patient exhibited clear breath sounds bilaterally on auscultation with no tachypnea, no wheezing, no rales, and no rhonchi. Labs were unremarkable. Swabs for influenza A and B Ags were both negative. Initial imaging via chest X-ray revealed clear lung fields bilaterally with no significant lung infiltrates or acute abnormalities. Results of the SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR nasopharyngeal swab were positive. Clinical presentation of the infection in this patient was characterized by a prolonged fever up to 38.9 °C that resolved on day 22. Results of antibody testing returned positive for both SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG and IgM antibodies on day 51. His symptoms continued to improve through day 53, and his first negative SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR nasopharyngeal swab was on day 60 after initial onset of symptoms (Table 1). This patient was managed as outpatient through regular monitoring via telemedicine.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

In a household of two individuals who both had COVID-19, the wife with milder upper respiratory involvement had a prolonged positive SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal swab test compared to her husband who had more severe, longer lasting symptoms. A positive swab test after the resolution of symptoms suggests the possibility of reinfection through household transmission. Among members of the same household, a retrospective case series in Wuhan, China involving a total of 155 household contacts of 85 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 revealed a 30% rate of transmission [2]. The wife potentially could have been exposed to the virus and reinfected in the time her husband remained symptomatic. Anti-SARS-CoV-2-specific IgM antibodies are detected in the early stages of infection and their levels are significantly reduced 4 weeks after onset of illness [4], therefore the detection of IgM antibodies in the wife over 7 weeks after initial onset of symptoms and 3 weeks after her recovery supports this hypothesis. The husband who had tested seropositive for anti-SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG and IgM antibodies on day 51 still tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid via nasopharyngeal swab on day 52, indicating that he could have remained infectious.

The period of infectiousness of COVID-19 remains unknown, however, and sustained viral detection may not necessarily correlate with virus transmissibility. Although both patients’ RT-PCR results on nasopharyngeal swab repeatedly returned positive, it is unclear whether the test reflects an actively contagious infection versus detection of viral load. Factors such as patient age, sex, prior medical history, and type of specimen obtained may all contribute to the duration of viral shedding [5, 6]. Elderly age has been found to be an independent factor associated with prolonged viral shedding of SARS-CoV-2 [5, 6]. Furthermore, the results of one study revealed the median duration of viral shedding from sputum specimens and nasopharyngeal specimens was 34 days and 19 days, respectively [6]. These findings have the potential implication of prolonged transmissibility as patients with COVID-19 shed the virus longer in their lower respiratory tracts, particularly among the elderly. Recent data on the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 among 790 personal contacts of patients who tested negative for the virus after recovering but later tested positive again showed no new confirmed cases from exposure during the re-positive period [3]. This raises the question whether a recovered patient with a PCR-positive sample still remains infectious.

Rapidly evolving knowledge about SARS-CoV-2 transmission will continue to impact clearance discharge criteria for infected patients. Current CDC guidelines on the discontinuation of home isolation for persons with COVID-19 offer a symptom-based strategy. Patients who have COVID-19 and are symptomatic may discontinue home isolation if at least 10 days have passed since initial onset of symptoms, and at least 24 hours have passed since resolution of fever without use of fever-reducing medication, and other symptoms have improved [9]. Patients with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 who never develop any COVID-19 symptoms may discontinue isolation 10 days after their first positive RT-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 ribonucleic acid (RNA) [9]. The protocol on how and when to ease social distancing guidelines requires a stronger understanding of any potential antibody-mediated immunity after infection. A recent study on the antibody response in laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infected patients show that IgG levels begin to decrease within 2-3 months after infection [7]. In another report, seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies was only 5.0% by point-of-care test on 61,075 participants from 35,883 randomly selected households in Spain [8]. These data currently do not support the model of herd immunity.

Limitations of this report include the small sample size, the similar ages of our two patients, and that the study population belonged to the same household. Additional examination is necessary to further understand the serological characteristics of recovered COVID-19 patients.

Conclusions

Patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 whose fever and respiratory symptoms have resolved may still continue to test positive for the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus after they begin to recover. Prolonged viral shedding may be contributing to sustained viral detection in recovered patients, however the low rate of secondary transmission in recovered COVID-19 patients who later re-test positive raises the question whether all seropositive patients are truly infectious. Our report demonstrates the need for caution when applying a symptom-based strategy for the discontinuation of isolation of COVID-19 patients in community settings in order to prevent further potential spread of this deadly virus.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent for publication of this report was obtained from the case subjects.

Author Contributions

Christine X.Q. Pham wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. Michelle Uttaburanont contributed to data collection and analysis, and critically reviewed the manuscript. Maciej Witkos contributed to data interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Wang B, Wang L, Kong X, Geng J, Xiao D, Ma C, Jiang XM, et al. Long-term coexistence of SARS-CoV-2 with antibody response in COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020.

doi pubmed - Wang Z, Ma W, Zheng X, Wu G, Zhang R. Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2. J Infect. 2020;81(1):179-182.

doi pubmed - Findings from investigation and analysis of re-positive cases. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a30402000000&bid=0030#.

- Liu X, Wang J, Xu X, Liao G, Chen Y, Hu CH. Patterns of IgG and IgM antibody response in COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):1269-1274.

doi pubmed - Yan D, Liu XY, Zhu YN, Huang L, Dan BT, Zhang GJ, Gao YH. Factors associated with prolonged viral shedding and impact of lopinavir/ritonavir treatment in hospitalised non-critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(1).

doi pubmed - Wang K, Zhang X, Sun J, Ye J, Wang F, Hua J, Zhang H, et al. Differences of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 shedding duration in sputum and nasopharyngeal swab specimens among adult inpatients with coronavirus disease 2019. Chest. 2020.

doi pubmed - Long QX, Tang XJ, Shi QL, Li Q, Deng HJ, Yuan J, Hu JL, et al. Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat Med. 2020;26(8):1200-1204.

doi pubmed - Pollan M, Perez-Gomez B, Pastor-Barriuso R, Oteo J, Hernan MA, Perez-Olmeda M, Sanmartin JL, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Spain (ENE-COVID): a nationwide, population-based seroepidemiological study. Lancet. 2020;396(10250):535-544.

doi - Disposition of non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/disposition-in-home-patients.html.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.