| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 12, Number 10, October 2021, pages 405-410

A Rare Case of Pulmonary-Renal Syndrome With Triple-Seropositive for Myeloperoxidase-Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasm Antibody (MPO-ANCA), Proteinase 3 (PR3)-ANCA and Anti-Glomerular Basement Membrane (GBM) Antibodies

Vanessa Palhaa, e , Ana Saa

, Teresa Pimentela

, Narciso Oliveiraa

, Sofia Rochab, Ana Isabel Silvac, Carlos Capelaa, d

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, Hospital de Braga, Braga, Portugal

bDepartment of Nephrology, Hospital de Braga, Braga, Portugal

cDepartment of Pathology, Hospital de Braga, Braga, Portugal

dLife and Health Sciences Research Institute, School of Medicine, University of Minho, Portugal

eCorresponding Author: Vanessa Palha, Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital de Braga, Sete Fontes - Sao Victor 4710-243 Braga, Portugal

Manuscript submitted July 2, 2021, accepted July 20, 2021, published online September 29, 2021

Short title: PRS With Triple-Seropositivity

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3742

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) disease and anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis are the main causes of pulmonary-renal syndrome (PRS). The concurrence of both ANCA - myeloperoxidase (MPO) and proteinase 3 (PR3) - and anti-GBM antibodies has been described, although positivity for all three antibodies has rarely been reported. The natural history of triple-positive patients as well as the best therapeutic approach remains unknown. We describe a case of an 80-year-old woman that presented to the emergency department with a 3-month history of progressive fatigue, malaise and anorexia, and 5 weeks of cough with blood-streaked sputum and progressive peripheral edema. Through the complementary study, a rare diagnosis of PRS with triple-seropositive for both ANCA (MPO and PR3) and anti-GBM antibodies was made in a patient with untreated chronic hepatitis B virus infection. She was treated with glucocorticoid, cyclophosphamide, plasma exchange and entecavir, with pulmonary recovery. Renal function did not improve. After 2 years, the patient is still in dialysis, but did not have relapse of alveolar hemorrhage and ANCA and anti-GBM antibody titers remain negative. The authors intend to warn to PRS, in particular this rare cause, since delaying diagnosis can lead to significant morbidity and mortality for patients.

Keywords: Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage; Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis; Pulmonary-renal syndrome; Vasculitis; Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; Anti-membrane basal glomerular antibody; Hepatitis B

| Introduction | ▴Top |

A pulmonary-renal syndrome (PRS) is characterized by the presence of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) associated with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN). PRS is a severe clinical condition requiring urgent and aggressive therapy. Anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) disease and anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) are the commonest causes of PRS [1]. Co-presentation of ANCA and anti-GBM antibodies was first described by O’Donoghue et al [2, 3] in 1980s [3, 4]. Since then, several studies have been describing this phenomenon called “double-positives” [4], but the pathophysiology remains uncertain [2, 4, 5]. About 10-40% [5, 6] of anti-GBM antibody-positive patients also had positive ANCA, usually myeloperoxidase (MPO)-ANCA [1, 2, 6, 7], and 5-14% [6] of ANCA-positive patients had positive anti-GBM antibodies [1]. The clinical presentation may be atypical [2], resulting in delay of the correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment [2, 8] with significant morbidity and mortality [2].

Although there were several reports with PRS who were double-positive, a triple-seropositive for both ANCA - MPO and proteinase 3 (PR3) - and anti-GBM antibodies has rarely been described. Herein, we describe an 80-year-old woman with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection that presented to the emergency department with PRS who was positive for MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA, and anti-GBM antibody.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

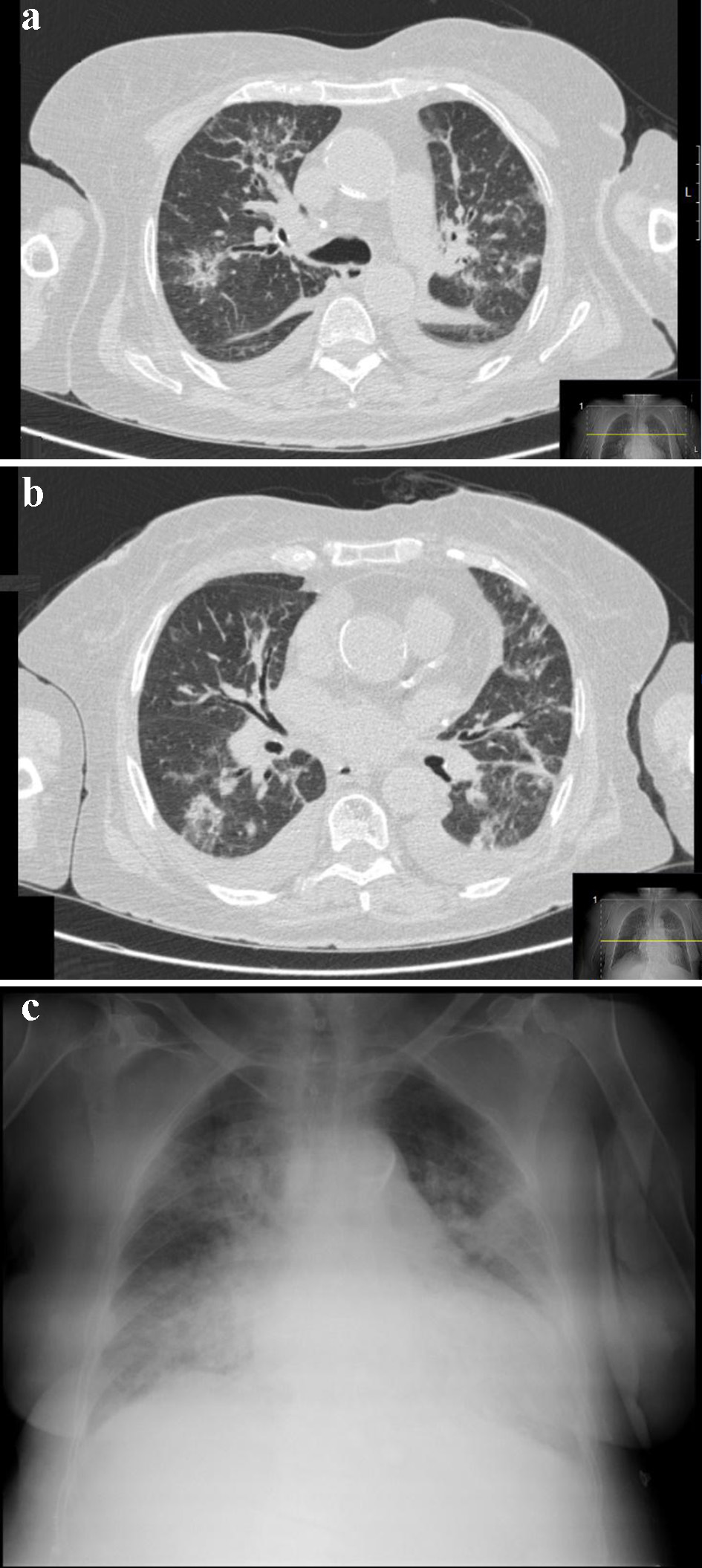

Investigations

We present a case of an 80-year-old Caucasian woman with history of arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus and ischemic cardiomyopathy with preserved ejection fraction. She presented to the emergency department with a 3-month history of progressive fatigue, malaise and anorexia, and 5 weeks of cough with blood-streaked sputum and progressive peripheral edema. She denied having fever, weight loss, arthralgia, and skin rash. Multifocal pneumonia and acute kidney injury (serum creatinine 5.69 mg/dL from a baseline of 0.99 mg/dL, reference range (RR): 0.6 - 1.2) associated with iron deficiency anemia (hemoglobin 7.6 g/dL, RR: 11.9 - 15.6) was diagnosed and she was admitted to intensive care unit (level 2). Intravenous (IV) fluid administration was started, as well as empiric amoxicillin-clavulanate and azithromycin, for 2 days, switched to piperacillin-tazobactam due to clinical worsening. Additional laboratory test showed elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), negative ANCA, anti-GBM and antistreptolysin O (ASO) antibodies titers, normal C3 and C4 levels, chronic HBV infection, negative anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and microscopic hematuria with subnephrotic proteinuria. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest and the abdomen revealed bilateral nodular infiltrates predominantly perihilar (Fig. 1a, b) and normal sized kidneys without hydronephrosis. During hospitalization, she had hemoptysis and bronchoscopy (FOB) with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed; bronchial secretions were seen, and bacterial, mycobacterial and fungal infection was excluded. Cytologic analysis showed alveolar macrophages and predominance of polymorphonuclear cells. The hemosiderin-laden macrophages were not identified.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Thorax CT scan (a, b) and chest X-ray (c) showing bilateral diffuse infiltrates of the lung. CT: computed tomography. |

Despite optimal medical management, renal function was worsening, and she was transferred to our hospital to initiate renal replacement therapy.

On admission, she was pale and afebrile, her blood pressure was 130/70 mm Hg and pulse rate was 87 beasts/min. She was tachypneic and oxygen saturation was 94% on 2 L/min nasal cannula. On chest auscultation, there were fine crackles in the lower two-thirds of bilateral hemithorax. She had peripheral edema and skin examination did not reveal any rash.

Diagnosis

On arrival in our hospital, new tests were performed: hemoglobin 8 g/dL (RR: 11.9 - 15.6), white blood cell count 13.2 × 109/L (RR: 4 - 11 × 109/L), C-reactive protein 79.8 mg/L (RR: < 3.0), ERS 66 mm/h (RR: < 20), serum creatinine 7.3 mg/dL (RR: 0.6 - 1.2) and blood urea nitrogen 197 mg/dL (RR: 15 - 39). HBV viral load was 337,600 IU/mL. Platelet count, coagulation tests, serum bilirubin (total and conjugated), aspartate and alanine aminotransferases were within normal range. Albumin and total serum protein were normal and immunoelectrophoresis revealed no monoclonal peak. Urinalysis showed 25 - 50 red blood cells/high-power field (RR: 0 - 2) and urinary protein 1.46 g/24 h (RR: < 0.05 - 0.08). Chest X-ray showed diffuse nodular infiltrate parenchymal disease involving both lungs (Fig. 1c).

Given the bilateral nodular pulmonary infiltrates, along with cough with blood-streaked sputum, hemoptysis and iron deficiency anemia, DAH seemed highly probable. Therefore, we suspected that the patient had a PRS and the autoimmune tests were repeated, on second day of hospitalization: MPO-ANCA 121.1 U/mL (RR: < 10), PR3-ANCA 312.6 U/mL (RR: < 20), anti-GBM antibody 202 U (RR: < 40) and rheumatoid factor 26 IU/mL (RR: < 15), normal C3 and C4 levels, and negative antinuclear antibody, cryoglobulins and anti-dsDNA (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Laboratory Data on Admission and in Our Hospital |

Treatment

On second day, IV high-dose methylprednisolone therapy was started (500 mg/day for 3 days), followed by oral prednisolone at 60 mg/day, without renal biopsy. Pulses of IV cyclophosphamide (7.5 mg/kg) given at intervals of 2 weeks as part of induction therapy and nine sessions of plasma exchange (PE) over 2 weeks were also started, until anti-GBM antibody and ANCA titers were undetectable. Entecavir 0.5 mg weekly was started too.

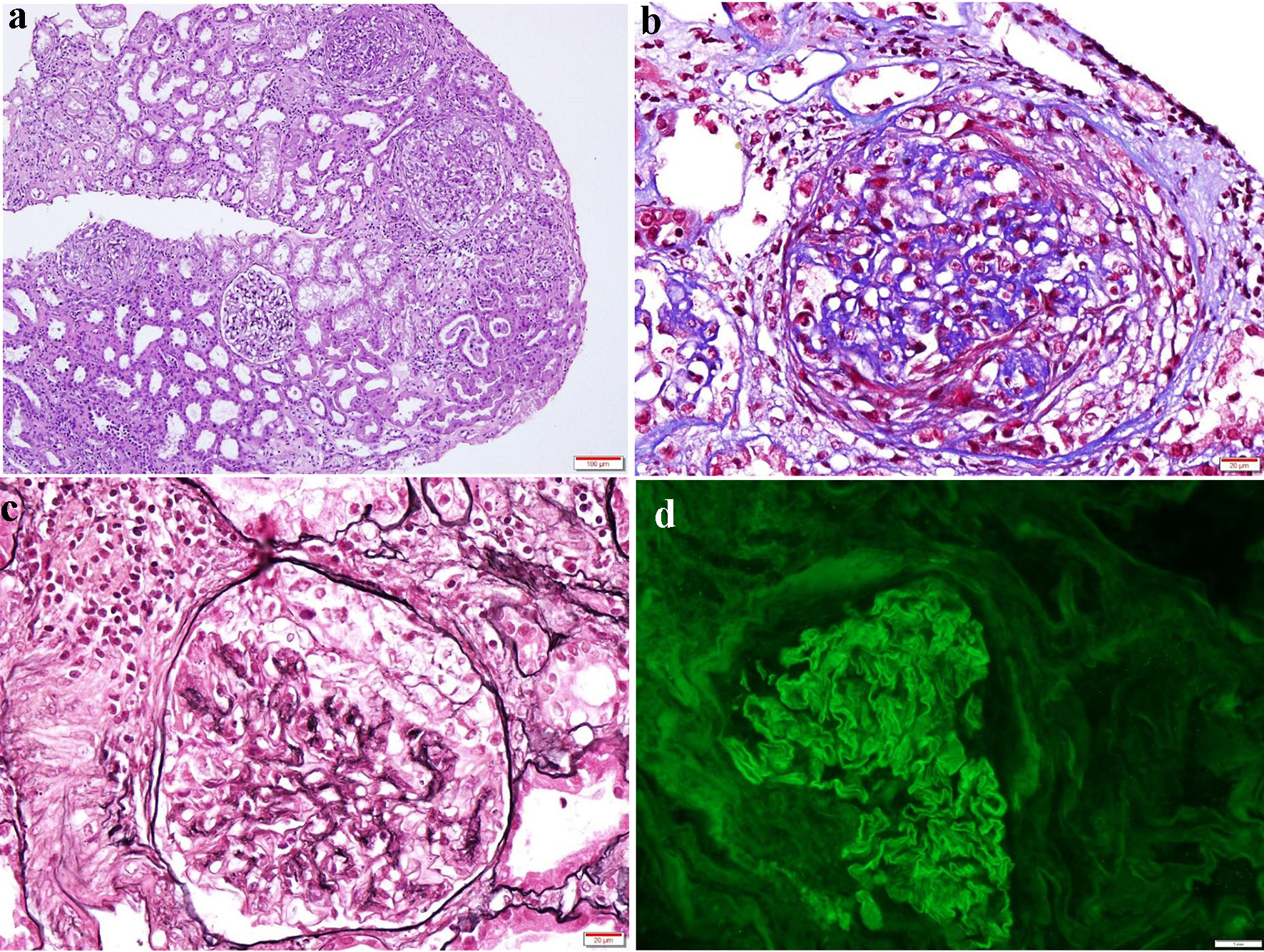

On sixth day, renal biopsy was performed, and cellular crescents were found in 57% glomeruli with focal fibrinoid necrosis and mildly interstitial fibrosis accompanied by moderate inflammatory infiltrate, without vasculitis (Fig. 2a-c). Immunofluorescence showed linear deposition of immunoglobulin G along the GBM (Fig. 2d). After these results, the patient maintained the ongoing therapy.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Kidney biopsy findings. Photomicrograph showing (a) three glomeruli with cellular crescents, associated with mildly interstitial fibrosis and moderate inflammatory infiltrate (H&E, × 100); (b) glomerulus with a cellular crescent (Masson’s trichrome, × 400); (c) Jones methenamine silver staining delineating glomerular and tubular basement, also showing a cellular crescent (× 400); (d) immunofluorescence staining revealing strong linear immunoglobulin G (3+) along the glomerular basement membrane. H&E: hematoxylin and eosin. |

Follow-up and outcomes

Progressive improvement occurred during 3 weeks of therapy, with resolution of hypoxemia, no recurrence of cough and blood-streaked sputum; however, renal function did not improve. On day 20, chest CT scan showed resolution of pulmonary infiltrates.

She was discharged after 34 days of hospitalization and despite this aggressive treatment, renal function did not recover. Oral glucocorticoid therapy was gradually reduced.

After 6 months of therapy with entecavir 0.5 mg weekly, HBV viral load became undetectable. Abdominal ultrasound showed normal liver morphology with a liver stiffness value compatible with F0-F1 (no or minimal fibrosis).

After 2 years, the patient is still dialysis-dependent, but did not have relapse of DAH and ANCA and anti-GBM antibody titers remain negatives.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The present report describes a case of PRS triple-seropositive for both ANCA (MPO and PR3) and anti-GBM antibodies, an entity rarely reported. Similar to double-positive, our patient has a hybrid disease phenotype [3], sharing features of AAV such as an older age [2-4, 8, 9] and a longer duration of symptoms before diagnosis [3, 4, 9], and features of anti-GBM disease such as severe disease manifestations at presentation [3-5] and typical linear deposit along the GBM on immunofluorescence for immunoglobulin on renal biopsy [5].

Our patient presented with DAH and severe renal failure requiring dialysis and, although immunosuppressive treatment and PE led to the resolution of DAH and constitutional symptoms, recovering of renal function did not occur. Based on these findings, we speculate that anti-GBM disease was the main disease phenotype [9]. However, natural history and prognosis of triple-positive patients remains poorly understood. There are few papers reporting a patient positive for all three antibodies. Sato et al presented a case of a male with known positivity for MPO-ANCA since the previous year, with renal-limited vasculitis and serological positivity for MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA and anti-GBM antibody who was successfully treated with glucocorticoid, cyclophosphamide, and PE, and recovered renal function [10]. McAdoo et al in their retrospective study reported a patient triple-positive who was positive for HCV but did not present a clinical feature in detail.

Although co-presentation with both ANCA (MPO or PR3) and anti-GBM antibodies is a well-recognized entity [3], the underlying mechanism of this association remains unclear [2, 3, 5, 6]. Several hypotheses have been proposed and the most attractive seems to be the existence of an ANCA-induced glomerular inflammation as a trigger to produce GBM autoantibodies [1, 2, 6-9]. In this patient, the longer duration of constitutional symptoms and the presence of both active and chronic lesions in renal biopsy also suggest that ANCA-mediated glomerular inflammation may have precede the onset of anti-GBM disease.

Furthermore, we speculate there may be an association between chronic HBV infection and the sequential formation of ANCA and anti-GBM antibodies. The role of HBV and HCV in the pathophysiology of ANCA-related vasculitis is a current topic of investigation. Ghonaim et al developed a study of chronic viral hepatitis patients and showed higher frequency of ANCA in chronic HCV infection than in the group control, but the same was not observed in chronic HBV group. However, in a study performed by Calhan et al, the frequency of ANCA was higher in chronic HBV patients in comparison with healthy controls [11]. HBV is associated with several extrahepatic manifestations such as vasculitis [11, 12] due to deposition of immune complexes [12]. The causal relationship between chronic HBV infection and polyarteritis nodosa was the only well established in the literature. Some reports have also been proposing the role of HBV in the formation of ANCA [12]. A case of a 64-year-old female with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis and HBV infection was reported [11]. Joshi et al also reported a case of a 33-year-old man with HBV-induced AAV causing subarachnoid hemorrhage, acute transverse myelitis and nephropathy [12]. However, there are insufficient data to determine whether HBV stimulates ANCA formation without triggering vasculitis or other immune-related manifestations. More studies and case reports are needed to verify this pathogenic link.

This patient was a real challenge. First, there are no specific clinical features of PRS, and several disorders may have a similar clinical presentation [1]. In our case, the first impression was multifocal pneumonia with sepsis-induced renal impairment. Despite therapy with broad-spectrum antibiotic, the patient was worsening. A history of cough with blood-streaked sputum and hemoptysis, iron deficiency anemia and bilateral nodular pulmonary infiltrates suggested DAH. The FOB with BAL excluded bacterial and fungal infection. BAL did not show hemosiderin-laden macrophages, a diagnostic feature of DAH, but false negative results may occur. Although the first autoimmune approach was negative, the suspicion was high and the laboratory tests were repeated, showing triple-seropositivity for both ANCA (MPO and PR3) and anti-GBM antibodies.

Second, due to its rarity, the natural history of triple-positive patients as well as the best therapeutic approach remains unknown. Once the anti-GBM disease seemed to be the main phenotype, we treated with immunosuppressive treatment (glucocorticoid and cyclophosphamide) and PE [5]. Constitutional symptoms and DAH disappeared, but the patient is still in dialysis. We believe that she was at high risk of relapse and so we kept close follow-up, in the first year every 3 months and then every 6 months, including monitoring of ANCA and anti-GBM titers. More investigation is needed to understand if this is the best approach in triple-positive patients.

In summary, we present a rare case of an 80-year-old woman with chronic HBV infection with PRS triple-seropositive for both ANCA (MPO and PR3) and anti-GBM antibodies, treated with glucocorticoid, cyclophosphamide, PE and entecavir. Two years later, she is still in dialysis, but with no relapse of DAH and ANCA and anti-GBM antibody titers remain negative.

Learning points

In the presence of hemoptysis, iron deficiency anemia and bilateral pulmonary nodular infiltrates, DAH must be excluded. The presence of DAH and RPGN characterizes the PRS. PRS is a rare but potentially life-threatening disorder which requires aggressive therapy to reduce morbidity and mortality. Early diagnosis is crucial and misdiagnosis with other diseases is common. Once PRS is suspected, evaluation of ANCA and anti-MBG antibody is mandatory. Co-presentation of both ANCA (MPO and PR3) and anti-GBM antibodies is an entity rarely described, which natural history and prognosis is unknown. In these patients, aggressive therapy with glucocorticoid, cyclophosphamide and PE may lead to resolution of DAH, but recovery of renal function may not occur.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained.

Author Contributions

VP was responsible for conception and writing the manuscript. AS, TP, NO and CC contributed to performing the diagnostic investigation and data analysis. SR was responsible for the patient’s nephrological evaluation, participated in the diagnostic investigation and provided interpretation of renal biopsy. AIS was responsible for the renal biopsy report and images. All authors revised critically the work for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Data Availability

Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

ANCA: anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody; AAV: ANCA-associated vasculitis; anti-GBM: anti-glomerular basement membrane; BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage; CT: computed tomography; DAH: diffuse alveolar hemorrhage; ERS: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FOB: bronchoscopy; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; IV: intravenous; MPO-ANCA: myeloperoxidase-anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody; PE: plasma exchange; PR3-ANCA: peroxidase 3-anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody; PRS: pulmonary-renal syndrome; RPGN: rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis; ASO: antistreptolysin O

| References | ▴Top |

- West SC, Arulkumaran N, Ind PW, Pusey CD. Pulmonary-renal syndrome: a life threatening but treatable condition. Postgrad Med J. 2013;89(1051):274-283.

doi pubmed - Omotoso BA, Cathro HP, Balogun RA. Crescentic glomerulonephritis with dual positive anti-GBM and C-ANCA/PR3 antibodies. Clin Nephrol Case Stud. 2016;4:5-10.

doi pubmed - McAdoo SP, Tanna A, Hruskova Z, Holm L, Weiner M, Arulkumaran N, Kang A, et al. Patients double-seropositive for ANCA and anti-GBM antibodies have varied renal survival, frequency of relapse, and outcomes compared to single-seropositive patients. Kidney Int. 2017;92(3):693-702.

doi pubmed - Canney M, Little MA. ANCA in anti-GBM disease: moving beyond a one-dimensional clinical phenotype. Kidney Int. 2017;92(3):544-546.

doi pubmed - McAdoo SP, Pusey CD. Anti-glomerular basement membrane disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(7):1162-1172.

doi pubmed - Geetha D, Jefferson JA. ANCA-associated vasculitis: core curriculum 2020. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(1):124-137.

doi pubmed - Levy JB, Hammad T, Coulthart A, Dougan T, Pusey CD. Clinical features and outcome of patients with both ANCA and anti-GBM antibodies. Kidney Int. 2004;66(4):1535-1540.

doi pubmed - Javed T, Vohra P. Crescentic Glomerulonephritis with Anti-GBM and p-ANCA Antibodies. Case Rep Nephrol. 2012;2012:132085.

doi pubmed - Denton M, Magee C, Niles J. Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(5 Part 1):W1.

doi pubmed - Sato N, Yokoi H, Imamaki H, Uchino E, Sakai K, Matsubara T, Tsukamoto T, et al. Renal-limited vasculitis with elevated levels of multiple antibodies. CEN Case Rep. 2017;6(1):79-84.

doi pubmed - Calhan T, Sahin A, Kahraman R, Altunoz ME, Ozbakir F, Ozdil K, Sokmen HM. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody frequency in chronic hepatitis B patients. Dis Markers. 2014;2014:982150.

doi pubmed - Joshi U, Subedi R, Gajurel BP. Hepatitis B virus induced cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-mediated vasculitis causing subarachnoid hemorrhage, acute transverse myelitis, and nephropathy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2017;11(1):91.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.