| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 13, Number 1, January 2022, pages 44-46

Emphysematous Cystitis: An Unusual Cause of Septic Shock

Younes Ait Tamlihata, b, Jean-Louis Le Bivica, Gilles Lardillona, Abdelhak Hakima

aService de Reanimation Polyvalente et Soins Continus, Centre Hospitalier de Saintonge, 17100 Saintes, France

bCorresponding Author: Younes Ait Tamlihat, Service de Reanimation Polyvalente et Soins Continus, Centre Hospitalier de Saintonge, 17100 Saintes, France

Manuscript submitted December 2, 2021, accepted January 12, 2022, published online January 17, 2022

Short title: An Unusual Case of Emphysematous Cystitis

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3874

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Emphysematous cystitis is a rare disease characterized by the presence of gas in the bladder wall and/or cavity. It predominates in diabetic women and its clinical symptoms are varied. We report a case of emphysematous cystitis in an unbalanced diabetic patient, discovered at the stage of septic shock and multivisceral failure following a cardiac decompensation with a rapidly unfavorable evolution. We suggest a probable role of low cardiac output in the genesis of this pathology in some patients.

Keywords: Emphysematous cystitis; Physiopathology; Infection; Septic shock

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Emphysematous cystitis (EC) is considered a rare form of complicated urinary tract infection and is characterized by the presence of air in the bladder wall and/or cavity. It most often affects diabetic women of average age between 60 and 70 years. Its clinical presentation is associated with abdominal pain, signs of cystitis and pneumaturia. However, 7% of patients do not present any symptoms [1]. We report an observation of EC discovered at the stage of septic shock and multivisceral failure with a rapidly unfavorable evolution.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 75-year-old man presented with a history of arterial hypertension, chronic atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes for about 10 years, moderate chronic renal failure, and myocardial infarction 11 years ago treated by coronary artery bypass grafting and requiring an implantable defibrillator in the face of a low left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) despite revascularization. His treatment included ramipril (1.25 mg twice a day), cardensiel (1.25 mg/day), aldactone (12.5 mg/day), fluindione (10 mg/day), metformin (700 mg/day) and furosemide (250 mg twice a day). The patient was initially admitted to cardiology for an anasarca state associated with a worsening of his exertional dyspnea requiring an increase in diuretic treatment (furosemide 500 mg twice a day and introduction of spironolactone 50 mg/day) and indwelling urinary catheterization. He was transferred 6 days later to a cardiology intensive care unit in view of the development of acute renal failure with recourse to dobutamine in view of the appearance of arterial hypotension associated with an LVEF of 20% and a decreasing aortic velocity integral time (VTI) on transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) control. The patient was rapidly transferred to the intensive care unit because of the increased inflammatory syndrome, oliguria and persistent hypotension. On arrival in the department, he was confused, hypothermic at 35.7 °C, in atrial tachycardia at 110/min, with a capillary blood glucose level of 2.55 g/L, mottling associated with deep hypotension of 70/20 mm Hg under dobutamine at 10 µg/kg/min, without any functional digestive signs or hematuria, but with cloudy and foul-smelling urinary residues. The admission blood test showed thrombocytopenia at 60 × 109/L, hyperleukocytosis at 18.8 × 109/L with inflammatory syndrome (C-reactive protein (CRP) 273 mg/L and procalcitonin 7.53 ng/L), and acute renal failure (creatinine 193 µmol/L, urea 37 mmol/L) without metabolic acidosis or hyperkalemia. Liver function tests were normal, troponins were elevated to 214.4 ng/L with no ST-segment changes on electrocardiogram (ECG), and hyperlactatemia was noted at 4.32 mmol/L. The glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level measured 3 days before his admission to the ward was 7.9%.

Diagnosis

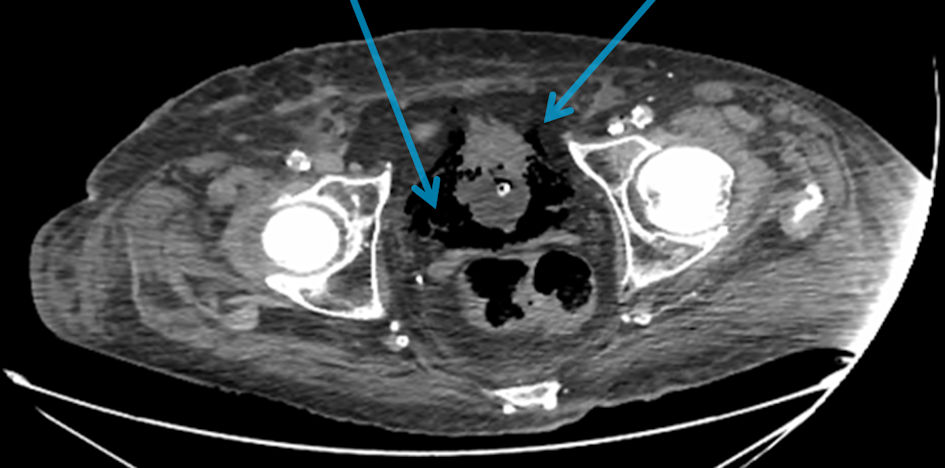

Faced with a vasoplegic hemodynamic profile with probable mixed cardiogenic and septic shock, a thoraco-abdomino-pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan was performed at the second hour of admission, which showed bilateral pleural effusions, cardiomegaly and the presence of intra- and peri-bladder air in favor of EC (Fig. 1), without signs of mesenteric ischemia or associated pyelonephritis.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Abdominal-pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan showing intra- and peri-bladder gas bubbles (arrows). |

Treatment

The initial management in the intensive care unit consisted of placing a central venous line in the left jugular vein under ultrasound, starting noradrenaline after the failure of vascular filling, introducing mineralocorticoids, intravenous insulin therapy, microbiological sampling and initiation of probabilistic antibiotic therapy with piperacillin/tazobactam and amikacin, as well as hemodynamic monitoring by transpulmonary thermodilution (PICCO Plus™ monitor) showing a collapsed cardiac output.

Follow-up and outcomes

The evolution was marked by cardiorespiratory arrest (CRA) due to ventricular tachycardia during the realization of CT, requiring an external cardiac massage for 3 min, 1 mg of adrenalin and an internal electric shock by his defibrillator. The patient was intubated afterwards and sedated in the absence of signs of awakening. On return to the ward, the patient presented a series of CRA with shockable rhythm and then electromechanical dissociation, always with a no flow at 0 min and a low flow of 3 - 4 min. The patient died rapidly from refractory shock and multivisceral failure at the ninth hour of admission, despite the increase in noradrenaline to 4 µg/kg/min and dobutamine to 20 µg/kg/min, the introduction of antiarrhythmics (amiodarone and xylocaine), and the use of hemofiltration. Afterwards, the cytobacteriological examination of urine (CBEU) culture was positive for Enterobacter cloacae and a sensitive methicillin Staphylococcus aureus was identified on a pair of blood cultures.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

A gas-producing infection can occur at three levels in the urinary tract, namely emphysematous pyelitis, emphysematous pyelonephritis and EC. The latter is a rare and severe infection of the lower urinary tract, affecting mainly diabetic patients up to 60-70% of cases, and most of them are women over 60 years old [1, 2]. It is characterized by the presence of air in the wall and also in the bladder lumen. However, its clinical presentation can be very varied, ranging from an asymptomatic state to true septic shock. According to a review of the literature including 135 cases, 7% of patients were completely asymptomatic [1]. In another literature review of 53 cases, abdominal pain was the most frequent symptom in more than 80% of the patients, pneumaturia was observed in only 26.7% of the patients (in 70% of the patients with bladder catheterization), abdominal tenderness was present in about two-thirds of the cases and only half of the patients presented the classical signs of lower urinary tract infection such as urgency, dysuria and pollakiuria. Abnormal body temperature was found in 52.9% of the cases and other symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea were also found with percentages less than 50% [2]. If the clinical symptoms are not specific, the current widespread use of medical imaging by CT scan makes the diagnosis of EC easier and allows to easily rule out the main differential diagnoses which are a vesico-vaginal fistula or a vesico-intestinal fistula [3, 4].

Many risk factors have been identified in EC such as diabetes, immunosuppression, neurogenic bladder, recurrent urinary tract infections and acute urine retention [1]. However, diabetes remains the main risk factor especially when it is unbalanced [5]. It should be noted that EC can occur in a patient with well-controlled diabetes as well as in the nondiabetic patient.

Microbiologically, Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumonia are the main germs involved in EC and the least common are Enterobacter aerogenes, Proteus mirabilis and Streptococcus spp. Although bacteria seem to be the most common, rare cases of fungal EC have been reported with Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis and Aspergillus fumigatus [1, 2]. In the present case, we obtained different results between CBEU and blood cultures. Rereading of the TTE loops did not objectify any additional image to suspect endocarditis. In another observation of EC, the authors reported a gram-negative blood culture with identification of Candida albicans in the urine [6].

The management of EC is usually medical, associating bladder drainage, glycemic control and broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic therapy with third-generation cephalosporins, penicillin with beta-lactam inhibitors, fluoroquinolones or sometimes carbapenems depending on bacterial identification and antibiogram. Recourse to surgery remains very rare and reserved for cases of failure of medical treatment and severe necrotizing infections [4]. The prognosis is generally favorable, but depends on early diagnosis and management. The overall mortality in EC is around 7% but may be higher in cases of evolution or association with emphysematous pyelonephritis [4].

From a pathophysiological point of view, the exact mechanism of gas development in the bladder wall and lumen is not yet elucidated. Among the hypotheses evoked, is that of bacterial production of carbon dioxide (CO2) by fermentation of glucose in the unbalanced diabetic patient with high blood sugar levels. Since emphysematous infections can occur in nondiabetic patients, it has been suggested that urinary lactulose and tissue proteins may be useful as a substrate for gas production [7]. Certainly, EC can be responsible for septic shock and thus cause hypotension. However, prolonged arterial hypotension or low cardiac output may also be involved in the development of EC by altering perfusion and local bladder microcirculation, thus favoring bacterial multiplication at this level. Our patient was initially admitted for cardiac decompensation without signs of myocardial necrosis or biological inflammatory syndrome. In another publication, it was reported a case of EC associated with emphysematous gastritis as a complication of an intensive care unit stay following traumatic hemorrhagic shock with profound hypotension and CRA in a 78-year-old nondiabetic patient [8]. In another example, an 81-year-old patient who developed EC after an intensive care unit stay following an acute coronary syndrome requiring coronary bypass surgery and valve replacement was reported [6]. In all three cases, we suggest a probable role of low cardiac output that precipitated the progression to EC.

EC is a rare, life-threatening infection of the lower urinary tract, most often affecting diabetic patients with a highly variable symptomatology. Its pathophysiology is not entirely clear and prolonged low cardiac output may be a factor favoring this disease in some frail patients.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

No funding was secured for this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

AY drafted the manuscript. LJL took care of the patient. LG and HA carried out the critical analysis of article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

CBEU: cytobacteriological examination of urine; CRA: cardiorespiratory arrest; ECG: electrocardiogram; LVEF: left ventricle ejection fraction; VTI: velocity integral time; TTE: transthoracic echocardiography

| References | ▴Top |

- Thomas AA, Lane BR, Thomas AZ, Remer EM, Campbell SC, Shoskes DA. Emphysematous cystitis: a review of 135 cases. BJU Int. 2007;100(1):17-20.

doi pubmed - Grupper M, Kravtsov A, Potasman I. Emphysematous cystitis: illustrative case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86(1):47-53.

doi pubmed - Eken A, Alma E. Emphysematous cystitis: The role of CT imaging and appropriate treatment. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7(11-12):E754-756.

doi pubmed - Amano M, Shimizu T. Emphysematous cystitis: a review of the literature. Intern Med. 2014;53(2):79-82.

doi pubmed - Bjurlin MA, Hurley SD, Kim DY, Cohn MR, Jordan MD, Kim R, Divakaruni N, et al. Clinical outcomes of nonoperative management in emphysematous urinary tract infections. Urology. 2012;79(6):1281-1285.

doi pubmed - Li S, Wang J, Hu J, He L, Wang C. Emphysematous pyelonephritis and cystitis: A case report and literature review. J Int Med Res. 2018;46(7):2954-2960.

doi pubmed - Meira C, Jeronimo A, Oliveira C, Amaro A, Granja C. Emphysematous cystitis—a case report. Braz J Infect Dis. 2008;12(6):552-554.

doi pubmed - Madokoro S, Yanagawa Y, Nagasawa H, Takeuchi I, Oode Y. Damage control management for thoracic trauma with cardiac arrest complicated by emphysematous gastritis and cystitis. Cureus. 2020;12(2):e7102.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.