| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 2, Number 2, April 2011, pages 39-43

Extensive Pneumatosis Intestinalis in Association With Celiac Disease: A Case Report

Sanjeev Dayala, b, Robert Bolton-Jonesa, Sheila Stallarda, Lazlo Romics, Jra

aDepartment of Surgery and Department of Gastroenterology, Victoria Infirmary, Greater Glasgow and Clyde NHS Trust, G42 9TY, UK

bCorresponding author: Sanjeev Dayal

Manuscript accepted for publication October 5, 2010

Short title: Pneumatosis Intestinalis and Celiac Disease

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/jmc63w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) is generally regarded as a worrying sign due to its relatively frequent association with serious conditions such as acute gastrointestinal necrosis. While PI can also be associated with a wide spectrum of benign conditions, its diagnosis as benign is usually accepted with the exclusion of gangrenous bowel, even in the absence of other clinical signs suggesting ischemia. We report a case of extensive PI in a patient with celiac disease and discuss its management and the role of diagnostic laparoscopy in this condition with emphasis on the different etiologies of PI.

Keywords: Pneumatosis intestinalis; Celiac disease; Laparoscopy; Management

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) is defined as gas in the bowel wall. PI can signify a wide spectrum of diseases that range from conditions with serious implications like bowel infarction and necrosis to other benign conditions like celiac disease (CD) [1]. PI has been classified into a benign primary form occurring in 15% of cases and a secondary form occurring in the remaining 85% of cases associated with obstructive and necrotic gastrointestinal disease and pulmonary disease [1, 2].

Differential diagnosis of PI is rather challenging if it is not associated with obvious bowel ischemia. Conversely, detection of PI on radiological imaging can misleadingly direct the patient’s work-up towards necrotic bowel, even if it is clinically not suggested. Since PI is generally regarded as a worrying sign, etiology of it is urgently sought in most cases. Furthermore, due to the widespread use of cross-sectional imaging in the acute setting these days, the diagnosis of benign PI has significantly increased making it very important for clinicians to be aware of this condition.

The association of PI with celiac disease is a very rare condition and to date only ten cases have been reported in the literature with only one in the UK [2]. We present a case of PI associated with refractory celiac disease, and discuss the role of sequential radiological imaging and diagnostic laparoscopy during its management.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

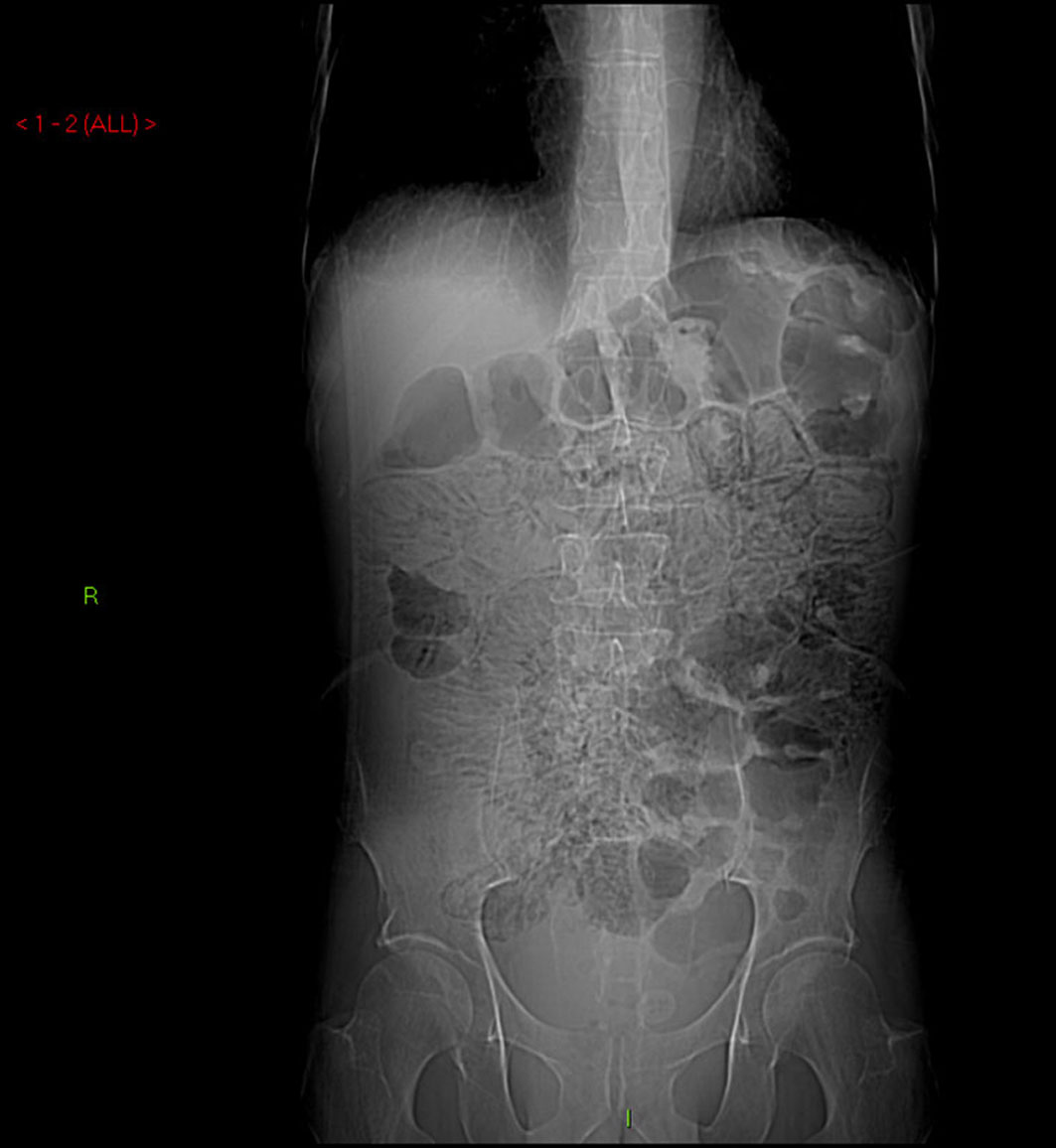

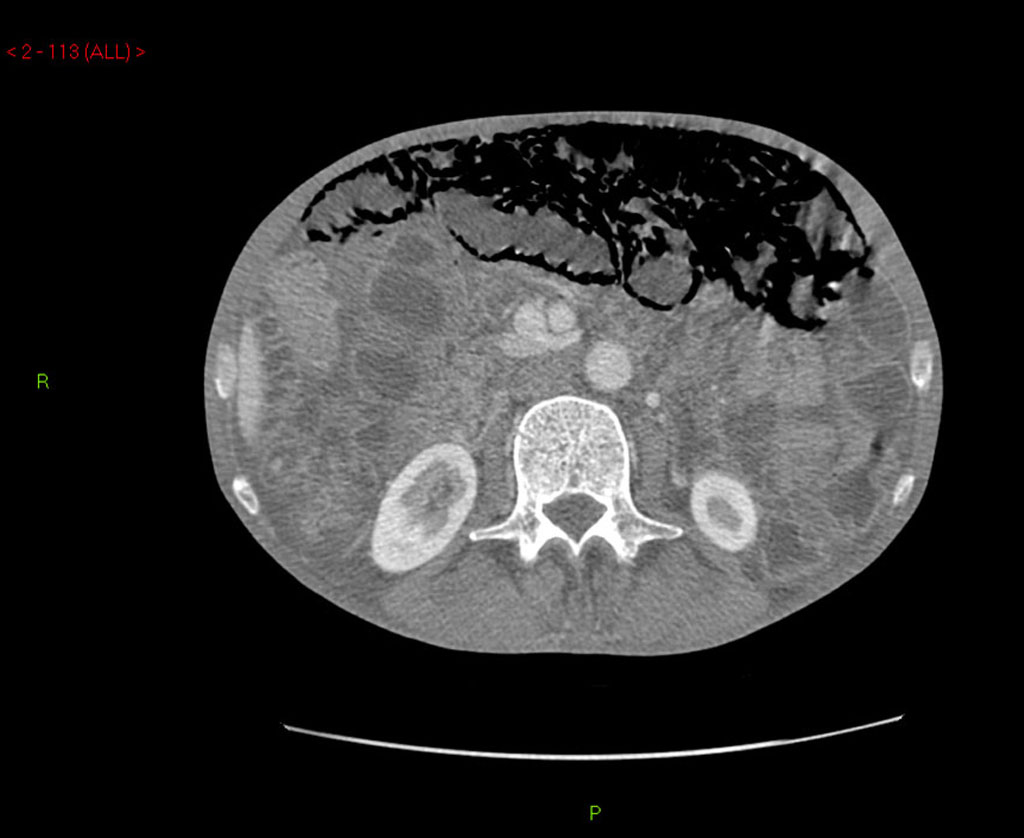

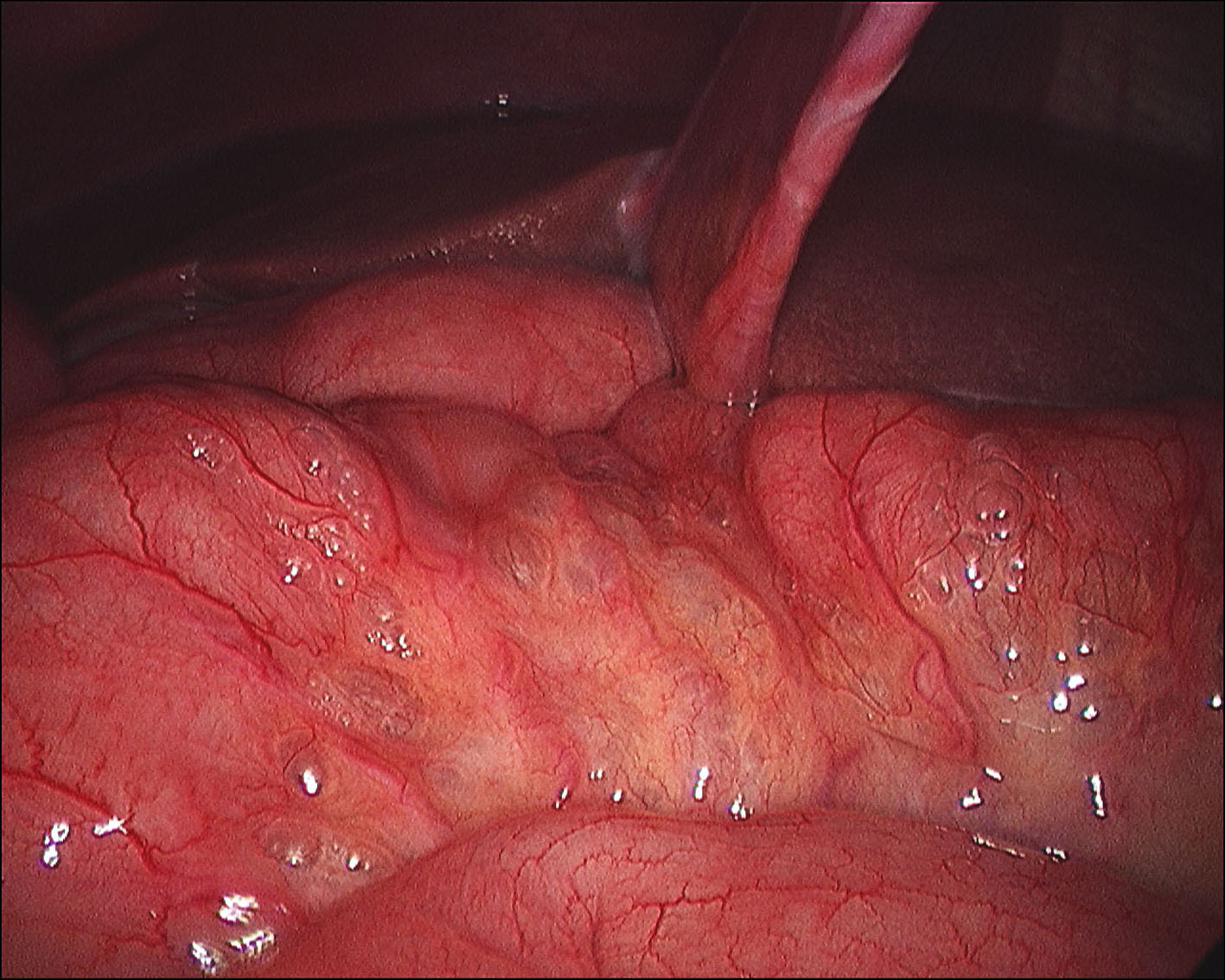

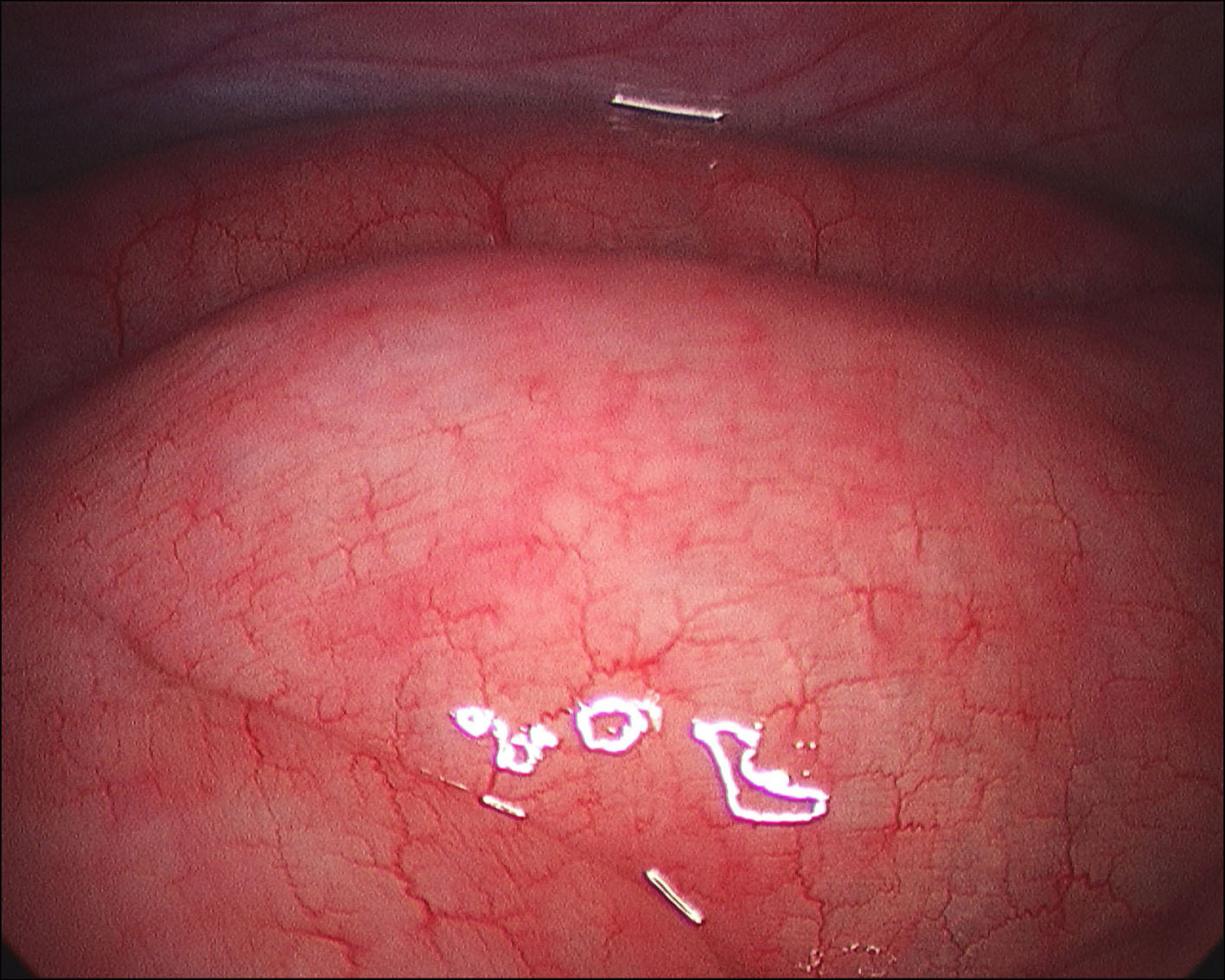

A 60-year-old man with no significant past medical history had been progressively unwell for eight weeks with complaints of abdominal bloating, diarrhea, decreased appetite and weight loss prior to his admission. Previously, he has been diagnosed with celiac disease confirmed on duodenal biopsies four months earlier, and subsequently started on gluten free diet but continued to lose weight. An abdominopelvic CT scan performed prior to his admission was unremarkable. On examination he was a thin built man with vague abdominal tenderness on palpation. His laboratory tests revealed normal white cell count and CRP level, although serum albumin level was quite low (17 g/L). Interestingly, routine abdominal X-ray and subsequent CT scan demonstrated extensive PI (Fig. 1, 2). While on clinical and biochemical grounds (normal blood gas analysis) ischemic bowel was an unlikely diagnosis, we proceeded with the least invasive option of a diagnostic laparoscopy to exclude the above with absolute certainty given the impressive radiological findings. Laparoscopy showed viable bowel with subserosal bubbles of air along the mesenteric border of the small bowel (Fig. 3). The small bowel wall in itself looked as though it had subserosal blebs clustered together (Fig. 4). A diagnosis of benign secondary PI was made. The patient’s further management included oxygen therapy, metronidazole and total parenteral nutrition, which significantly improved his diarrhea initially. On the tenth postoperative day, a barium follow through ruled out ulcerative jejunitis and EATL (Enteropathy Associated T-cell Lymphoma) and showed full resolution of the previous extensive PI. This was also confirmed by an abdomino-pelvic CT scan.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Abdominal X-ray demonstrating extensive pneumatosis intestinalis (PI). |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Abdominal CT scan demonstrating extensive pneumatosis intestinalis (PI). |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Laparoscopy showing viable bowel with subserosal bubbles of air along the mesenteric border of the small bowel. |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Laparoscopy showing the small bowel wall. |

Unfortunately, the patient did not tolerate semi-elemental enteral feeding due to worsening diarrhea and this significantly limited treatment options. Clostidrium difficile infection and other infective pathology were ruled out by stool cultures and CMV, HIV and autoimmune etiology were ruled out by negative serology. Furthermore, inflammatory bowel disease and microscopic colitis were excluded by colonoscopic biopsies. The nutritional status of the patient continued to deteriorate despite parenteral nutrition and his serum albumin dropped to 11 g/L. Immuno-histochemical staining of intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) in his duodenal biopsies did not confirm the clinical suspicion of refractory celiac disease. Regrettably, the patient’s general condition and diarrhea continued to worsen and he passed away five weeks after his admission.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Secondary PI in adults can be caused by a wide range of diseases. These range from COPD, immuno-compromised states, collagen vascular disease, celiac disease, bowel trauma, bowel obstruction, infections secondary to CMV, Clostidrium difficile and HIV, to immediate life threatening conditions like bowel infarction and necrosis [3]. PI can affect any part of the GI tract, although most frequently involves the small bowel (42%) and the colon (36%) [4]. While subserosal cysts are more common in the small bowel, submucosal cysts are more frequent findings in the colon.

Different etiologies have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of PI. The mechanical theory suggests that gas dissects into the bowel wall secondary to disruption in the mucosal integrity due to various factors such as ischemia, trauma or infection [5]. It has also been suggested that gas can tract through the tissues and along the root of the mesentery in patients with COPD [5]. The biochemical theory, on the other hand, proposes that luminal bacteria produce significant amounts of hydrogen as a result of fermentation of mostly carbohydrates, which is then forced into the bowel wall as intraluminal pressure rises. Hydrogen content of the cysts has been reported to be as high as 50% [6]. The bacterial theory proposes that gas-forming bacteria enter the bowel wall through breaches in the mucosa. Resolution of PI has been seen with antibiotics leading some to believe that bacteria may have a role to play in this [7].

Symptoms and signs of PI can be related to its presence or the underlying disorder giving rise to it. They also depend on which part of the bowel is affected. Small bowel pneumatosis has been reported to cause vomiting, abdominal distension, weight loss, abdominal pain and diarrhea. Large bowel pneumotosis on the other hand has been reported to cause diarrhea, hematochezia, abdominal pain and distension, constipation and tenesmus [4].

Diagnosis of PI can be made using different radiological imaging. An abdominal radiograph can identify PI in 66% of cases [8]. It is seen as different patterns of radiolucencies in the form of linear, curvilinear, small bubbles or collection of cysts within the bowel wall. Cystic collections of gas are more suggestive of primary PI. PI associated with portal venous gas is an ominous sign for bowel ischemia. A CT Scan is more sensitive in detecting PI and may also suggest underlying cause as compared to an abdominal x-ray [9]. However, given that its sensitivity to diagnose ischemic bowel is only in the range of 82% [10], it can make reporting PI secondary to ischemic bowel challenging for the radiologist in the absence of portal venous gas. To operate or not to operate can be the main dilemma in the management of PI. Intraabdominal catastrophe is clinically obvious in most cases however sometimes this may not be so on initial presentation. One can argue the need for a diagnostic laparoscopy in this patient given that he had no signs of peritonism, normal inflammatory markers and a normal arterial blood gas. The role of diagnostic laparoscopy however has been found to be reliable and accurate in the setting of PI associated with celiac disease [8, 11].

Once an acute intra abdominal emergency has been excluded the management of PI is largely conservative [12]. Oxygen therapy, antibiotics and elemental diet have been found to be mainstays of treatment, as we did in our patient. The rationale for the use of oxygen has been postulated to be two-fold. Firstly, oxygen is toxic to the anaerobic bacteria thought to be responsible for the gas production and secondly, increased partial pressures of oxygen in the venous blood and decreased partial pressure of nonoxygen gases create a diffusion gradient allowing the absorption of the latter [13]. Optimal amount and duration of oxygen therapy is however not known [14]. The rationale for using antibiotics is again targeted at the anaerobic bacteria. The successful application of metronidazole in treating PI has been described before [15]. Similarly, elemental diet has been reported to alter the colonic microflora, thereby helping in the resolution of PI [16].

Complications are seen in approximately 3% of cases with PI [17]. These include small and large bowel obstruction, volvulus, intussusception, pneumoperitoneum and hemorrhage, and these may warrant surgery.

Intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) in uncomplicated celiac disease have been shown to express CD3+ and CD8+ receptors which can be identified with immunohistochemical staining. In refractory CD, the IELs have been found to be abnormal expressing only intracytoplasmic CD3 but not surface CD8 [18]. This aberrant clonal intraepithelial T cell population is however found only in 75% of cases of refractory celiac disease [19]. In our patient, infectious causes, malabsorption, ulcerative jejunitis, EATL, autoimmune enteropathy, inflammatory bowel disease and microscopic colitis were all ruled out. Since post mortem examination was not carried out due to lack of family’s consent, we can only assume given the clinical course, that there was a significant association between celiac disease and pneumatosis intestinalis and the patient’s death.

Conclusion

PI secondary to celiac disease is a rare but well-established condition. It can confront clinicians with the dilemma to operate or not to operate when faced with impressive radiological findings and the serious implications of PI and ischemic bowel. We believe that although diagnostic laparoscopy can be used to confirm PI to be benign, it is not always necessary to perform given that our understanding of this condition has greatly improved. Treating the underlying cause is the mainstay of treatment to achieve full resolution of PI.

Conflict of Interest

None.

| References | ▴Top |

- Donati F, Boraschi P, Giusti S, Spallanzani S. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis: imaging findings with colonoscopy correlation. Dig Liver Dis 2007;39(1):87-90.

pubmed doi - Nathan H, Singhal S, Cameron JL. Benign pneumatosis intestinalis in the setting of celiac disease. J Gastrointest Surg 2006;10(6):890-894.

pubmed doi - Knechtle SJ, Davidoff AM, Rice RP. Pneumatosis intestinalis. Surgical management and clinical outcome. Ann Surg 1990;212(2):160-165.

pubmed doi - Jamart J. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. A statistical study of 919 cases. Acta Hepatogastroenterol (Stuttg) 1979;26(5):419-422.

pubmed - Pear BL. Pneumatosis intestinalis: a review. Radiology 1998;207(1):13-19.

pubmed - Sartor RB, Murphy ME, Rydzak E. Miscellaneous inflammatory and structural disorders of the colon. In: Yamada T, Alpers D, Laine L, eds. Textbook of Gastroenterology. 4rd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia; 2003:1791-816.

- Ellis BW. Symptomatic treatment of primary pneumatosis coli with metronidazole. Br Med J 1980;280(6216):763-764.

pubmed doi - Mehta SN, Friedman G, Fried GM, Mayrand S. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis: laparoscopic features. Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91(12):2610-2612.

pubmed - Ihara E, Harada N, Motomura S, Chijiiwa Y. A new approach to Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis by target air-enema CT. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93(7):1163-1164.

pubmed doi - Wiesner W, Mortele KJ, Glickman JN, Ji H, Ros PR. Pneumatosis intestinalis and portomesenteric venous gas in intestinal ischemia: correlation of CT findings with severity of ischemia and clinical outcome. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001;177(6):1319-1323.

pubmed - Terzic A, Holzinger F, Klaiber C. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis as a complication of celiac disease. Surg Endosc 2001;15(11):1360-1361.

pubmed doi - Greenstein AJ, Nguyen SQ, Berlin A, Corona J, Lee J, Wong E, Factor SH, et al. Pneumatosis intestinalis in adults: management, surgical indications, and risk factors for mortality. J Gastrointest Surg 2007;11(10):1268-1274.

pubmed doi - Levitt MD, Olsson S. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis and high breath H2 excretion: insights into the role of H2 in this condition. Gastroenterology 1995;108(5):1560-1565.

pubmed doi - Heng Y, Schuffler MD, Haggitt RC, Rohrmann CA. Pneumatosis intestinalis: a review. Am J Gastroenterol 1995;90(10):1747-1758.

pubmed - Jauhonen P, Lehtola J, Karttunen T. Treatment of pneumatosis coli with metronidazole. Endoscopic follow-up of one case. Dis Colon Rectum 1987;30(10):800-801.

pubmed doi - Johnston BT, McFarland RJ. Elemental diet in the treatment of pneumatosis coli. Scand J Gastroenterol 1995;30(12):1224-1227.

pubmed doi - Galandiuk S, Fazio VW. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. A review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum 1986;29(5):358-363.

pubmed doi - Ho-Yen C, Chang F, van der Walt J, Mitchell T, Ciclitira P. Recent advances in refractory coeliac disease: a review. Histopathology 2009;54(7):783-795.

pubmed doi - Cellier C, Delabesse E, Helmer C, Patey N, Matuchansky C, Jabri B, Macintyre E, et al. Refractory sprue, coeliac disease, and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. French Coeliac Disease Study Group. Lancet 2000;356(9225):203-208.

pubmed doi

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.