| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 4, Number 3, March 2013, pages 121-124

The Girl With the Headache and Double Vision

Vasantha K. Kondamudia, Irina Erlikha, Evgeniy Levieva, b, Sherly Abrahama, Apar Bainsa, Seema Tayala

aDepartment of Family Medicine, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, USA

bCorresponding author: Evgeniy Leviev, Department of Family Medicine, 121 Dekalb Avenue, Brooklyn, NY, 11201, USA

Manuscript accepted for publication September 24, 2012

Short title: Headache and Double Vision

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/jmc913w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), previously referred to as pseudotumor cerebri is a disorder that is characterized by increased intracranial pressure caused by buildup or poor absorption of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) without a space-occupying intracranial lesion or hydrocephalus. We report a case of a 17 year old female who presented to her primary care physician (PCP) for evaluation of a headache. Upon performance of computed tomography (CT scan) of the head and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain: no evidence of mass lesion or abnormal enhancement in the brain parenchyma, neither evidences of acute intracranial pathology was present. Lumbar puncture (LP) was done resulting in improvement of the patient’s symptoms and decreased intensity of headache. We will discuss the management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) with emphasis on the different etiologies and new diagnostic criteria for this disease.

Keywords: Idiopathic intracranial hypertension; Headache; Double vision

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a relatively rare disease. An epidemiological study in Iowa and Louisiana estimated the incidence of IIH to range from 0.9 to 1 per 100,000 in the general population [1]. There is a higher incidence in obese women between the ages of 15 and 44 years old (4 to 21 per 100,000 populations) [2]. The true incidence of this condition is probably more common than is projected from these studies, since many cases present as headache without papilledema and such cases can be potentially misdiagnosed as other headache syndromes [3]. The most common presenting symptom is headache, occurring in more than 90% of cases. Less frequently, patients report neck pain, back and shoulder pain. Other common non-visual manifestations include reported sensation of pulsatile intracranial noises, dizziness, nausea and vomiting [4]. Transient visual obscurations are the most common visual symptoms, but patients may also report blurred vision, photophobia and double vision [5].

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 17-year-old female with past medical history (PMH) of mild persistent asthma, history of parotid carcinoma status post resection 5 years prior, lymphedema, headaches, morbid obesity, and oligomenorrhea presented to PCP for evaluation of her headache lasting about 2 weeks. She described her headaches as moderate to severe, “behind her eyes”, burning in nature, non-radiating, of gradual onset, occasionally aggravated by exposure to light, initially alleviated by Excedrin and sleep, and associated with persistent double vision for one week. The headaches were different from the previous episodes experienced by the patient, which were mostly dull in nature and occipital in location. The patient did not report any history of trauma, fever, neck stiffness, photopsia, nausea, vomiting, weakness of body, seizures, tinnitus or vision loss. The patient had no known drug allergies and her family history was significant for obesity, stroke, diabetes, hypertension, HIV, breast and ovarian cancer. Social history was non-contributory.

Physical exam of the patient revealed vital signs within normal limits. Head and neck exam was remarkable for the presence of a well-healed 3 cm scar in the submandibular region. Visual acuity testing was 20/20 bilaterally; diplopia on forward gaze, (not on lateral or vertical gaze) was found. Respiratory, cardiovascular and abdominal exams were unremarkable. Extremities examination revealed non-pitting edema in bilateral lower extremities. Neurologic exam was grossly unremarkable with the exception of diplopia as described above.

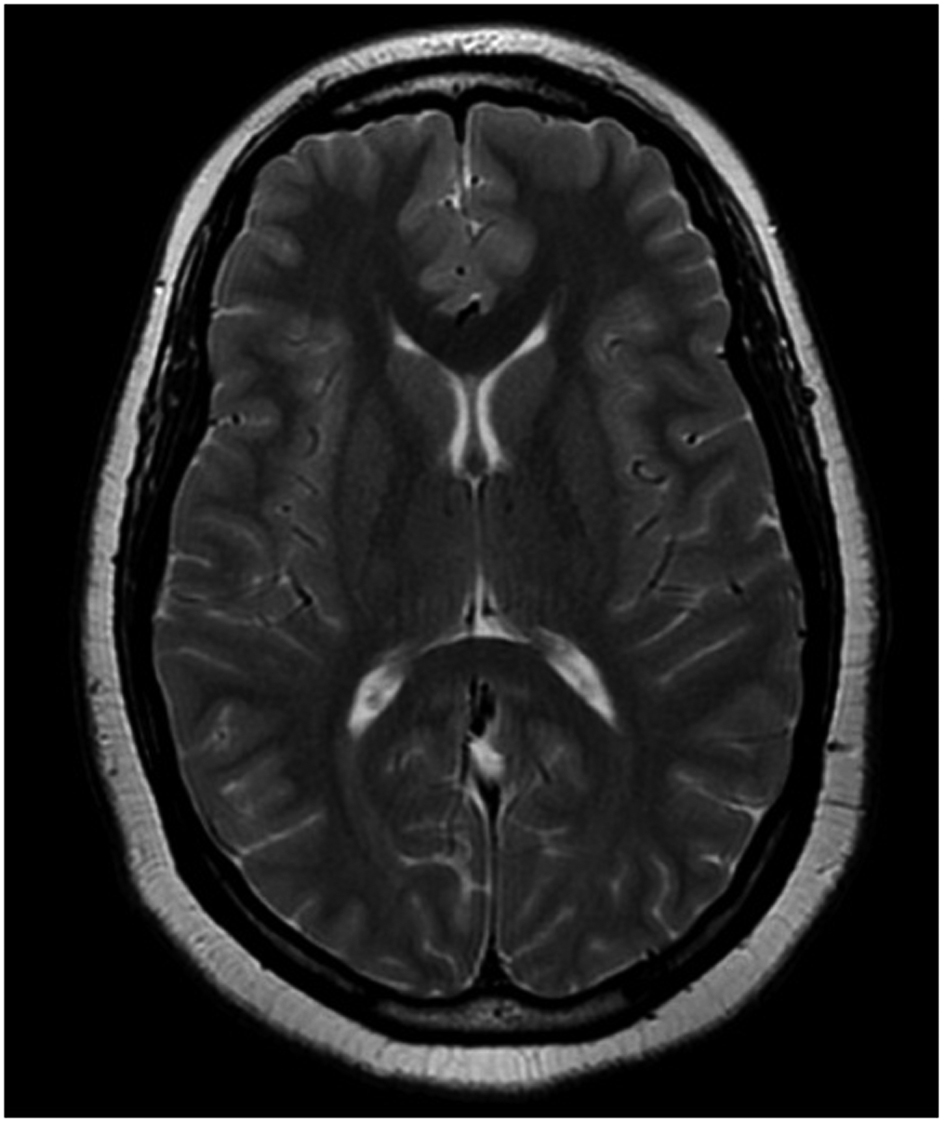

The patient was referred to ophthalmology for the evaluation of diplopia. The consultation indicated the presence of papilledema bilaterally (Fig. 1) and the patient was admitted to the hospital for further evaluation. Initial lab work was within normal limits except for an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 68 mm/hr. Computed tomography (CT scan) of the head and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain (Fig. 2) showed no evidence of mass lesion or abnormal enhancements in the brain parenchyma. Lumbar puncture (LP) was performed to collect 21 mL of CSF at an opening pressure of 35 mm H2O. Analysis of CSF was within normal limits.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Papilledema as seen on fundoscopic exam. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. MRI brain ruled out intracranial mass lesions, venous sinus thrombosis and hydrocephalus. |

Given the clinical presentation and results of diagnostic work up, patient was diagnosed with idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH). Patient was started on Acetazolamide and symptomatic improvement was noted. Patient was subsequently discharged to follow up on an outpatient basis. Patient followed up at 3 and 6 months after discharge and reported complete resolution of both the headaches and diplopia.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The pathogenesis of raised intracranial pressure remains unclear, no single theory has been able to provide a comprehensive answer: therefore, there is little consensus as to its cause. A multiplicity of factors including altered CSF dynamics, obesity, sex hormones and an underlying prothrombotic abnormality have been suggested to play a role in the pathogenesis of this condition [6]. Endocrine pathologies like Addison's disease, hypoparathyroidism, Cushing's disease and diseases like obesity, chronic renal failure (CRF), iron deficiency anemia, polycystic ovary syndrome (POS), head trauma, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) may lead to increased risk for idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) [7-10]. Certain medications, for example oral contraceptive pills (OCP), nitrofurantoin, nalidixic acid, phenytoin, sulfa drugs, tetracycline, steroids, isotretinoin, and vitamin A can induce this condition [11]. The original criteria for idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) were described by Dandy in 1937 [12]. They were modified by Smith in 1985 and amended further by Digre and Corbett in 2001 [13].

Modified Dandy criteria

1) Symptoms of raised intracranial pressure (headache, nausea, vomiting, transient visual obscurations, or papilledema); 2) No localizing signs with the exception of abducens (sixth) nerve palsy; 3) The patient is awake and alert; 4) Normal findings on computed tomography (CT scan) of head and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of brain without evidence of venous sinus thrombosis; 5) Elevated CSF opening pressure and normal biochemical and cytological composition of CSF; 6) No other explanation for the raised intracranial pressure [13].

Diagnostic studies

To confirm the diagnosis, as well as to exclude alternative causes, several investigations are required. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium enhancement is the study of choice for all patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) because it provides sensitive images to rule out meningeal inflammation, venous sinus thrombosis, intracerebral masses and hydrocephalus [14]. Occasionally magnetic resonance venography (MRV) may be used for diagnosis of IIH. However, this method might not add significantly to the evaluation of typical idiopathic IIH but may be indicated in atypical cases (for example, male, thin, or elderly patients) [15]. A CT scan of the head it is not as sensitive as MRI, but less expensive and adequate to identify large tumors or lesions. A CT scan may be necessary for patients with contraindications to MR imaging (pacemakers, metallic clips in head, metallic foreign bodies) and obese or claustrophobic patients [16].

Lumbar puncture is performed in order to measure the opening pressure after ruling out the possibility of an intracranial space-occupying mass lesion. For the diagnosis of IIH, the CSF opening pressure should be more than 250 mm of water measured with the patient in the lateral decubitus position and the legs as relaxed as possible [17]. Sometimes, sonography can be used to identify intracranial hypertension by measuring the diameter of the optic nerve sheath in emergent settings [18].

Treatment strategies

Patients without visual loss most often are treated with a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor to lower the intracranial pressure (ICP). Acetazolamide reduces the production of CSF by decreasing sodium ion transport across the choroidal epithelium [19]. Topiramate, an antiepileptic drug, is another treatment option. It possibly reduces CSF production by carbonic anhydrase inhibition and could also help patients to lose weight [20]. A recent study found that weight loss, rather than acetazolamide, caused improvement in papilledema [21]. In patients with severe symptoms, early visual field loss, or poor response to standard medical therapy, some clinicians utilize a short course of high-dose corticosteroids. However, steroids are no longer used routinely in the treatment of IIH due to their multiple side effects and also the reports of IIH like picture caused by the steroid withdrawal [22].

For patients who have progressive visual field loss, currently 2 general surgical approaches can be considered: CSF shunting procedures or optic nerve sheath fenestration. Several studies have shown the effectiveness of optic nerve sheath fenestration (ONSF) in improving papilledema and visual function [23]. In contrast to CSF diversion procedures, optic nerve sheath fenestration (ONSF) is less effective at reducing CSF pressure or relieving headache and is best not carried out as the primary procedure for treating intractable headache in patients with IIH [23]. Post-operative complications rates can be as high as 40% and include transient ocular motility disturbance, pupillary dysfunction and retinal vascular complications [24]. Lumboperitoneal (LP) shunt placement has emerged as the most widely performed CSF diversion procedure in patients with IIH to facilitate drainage of excess CSF. LP shunts result in rapid resolution of symptoms of elevated ICP and recent studies have shown encouraging evidence of its efficacy [25]. Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts are equally effective; however most neurosurgeons prefer LP shunt because insertion of VP shunt can be a difficult task in patients with IIH with small sized ventricles [26].

In view of the significant visual morbidity, careful follow-up of patients with IIH is needed. This is best done by a team which includes neurologist, ophthalmologist and primary care physician. The frequency of such follow-up examinations should be individualized according to the patient’s severity of symptoms and signs. Newly diagnosed patients and those with visual impairment may need to be evaluated every 2 - 4 weeks until their condition is stabilized. Stable patients may be followed up every 3 - 6 months [27].

Disclosure

No relevant financial affiliations or conflicts of interest to disclose.

| References | ▴Top |

- Durcan FJ, Corbett JJ, Wall M. The incidence of pseudotumor cerebri. Population studies in Iowa and Louisiana. Arch Neurol. 1988;45(8):875-877.

doi pubmed - Radhakrishnan K, Ahlskog JE, Cross SA, Kurland LT, O'Fallon WM. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Descriptive epidemiology in Rochester, Minn, 1976 to 1990. Arch Neurol. 1993;50(1):78-80.

doi pubmed - Bono F, Messina D, Giliberto C, Cristiano D, Broussard G, Fera F, Condino F, et al. Bilateral transverse sinus stenosis predicts IIH without papilledema in patients with migraine. Neurology. 2006;67(3):419-423.

doi pubmed - Galvin JA, Van Stavern GP. Clinical characterization of idiopathic intracranial hypertension at the Detroit Medical Center. J Neurol Sci. 2004;223(2):157-160.

doi pubmed - Wall M, George D. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. A prospective study of 50 patients. Brain. 1991;114 (Pt 1A):155-180.

pubmed - Johnston I, Hawke S, Halmagyi M, Teo C. The pseudotumor syndrome. Disorders of cerebrospinal fluid circulation causing intracranial hypertension without ventriculomegaly. Arch Neurol. 1991;48(7):740-747.

doi pubmed - Condulis N, Germain G, Charest N, Levy S, Carpenter TO. Pseudotumor cerebri: a presenting manifestation of Addison's disease. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1997;36(12):711-713.

doi - Sheldon RS, Becker WJ, Hanley DA, Culver RL. Hypoparathyroidism and pseudotumor cerebri: an infrequent clinical association. Can J Neurol Sci. 1987;14(4):622-625.

pubmed - Dave S, Longmuir R, Shah VA, Wall M, Lee AG. Intracranial hypertension in systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Ophthalmol. 2008;23(2):127-133.

doi pubmed - Glueck CJ, Iyengar S, Goldenberg N, Smith LS, Wang P. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: associations with coagulation disorders and polycystic-ovary syndrome. J Lab Clin Med. 2003;142(1):35-45.

doi - Binder DK, Horton JC, Lawton MT, McDermott MW. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurosurgery. 2004;54(3):538-551; discussion 551-532.

- Dandy WE. Intracranial Pressure without Brain Tumor: Diagnosis and Treatment. Ann Surg. 1937;106(4):492-513.

doi pubmed - Digre KB, Corbett JJ. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). The Neurologist 2001;7:2-67.

- Friedman DI, Jacobson DM. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2002;59(10):1492-1495.

doi - Lee AG, Brazis PW. Magnetic resonance venography in idiopathic pseudotumor cerebri. J Neuroophthalmol. 2000;20(1):12-13.

doi - Friedman DI. Papilledema and pseudotumor cerebri. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2001;14(1):129-147, ix.

pubmed - Corbett JJ, Mehta MP. Cerebrospinal fluid pressure in normal obese subjects and patients with pseudotumor cerebri. Neurology. 1983;33(10):1386-1388.

doi - Stone MB. Ultrasound diagnosis of papilledema and increased intracranial pressure in pseudotumor cerebri. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27(3):376 e371-376 e372.

- Tomsak RL, Niffenegger AS, Remler BF. Treatment of pseudotumor cerebri with Diamox (acetazolamide). J Clin Neuro-ophthalmol 1988; 8:93-98.

- Dodgson SJ, Shank RP, Maryanoff BE. Topiramate as an inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes. Epilepsia. 2000;41(Suppl 1):S35-39.

doi pubmed - Johnson LN, Krohel GB, Madsen RW, March GA, Jr. The role of weight loss and acetazolamide in the treatment of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Ophthalmology. 1998;105(12):2313-2317.

doi - Liu GT, Kay MD, Bienfang DC, Schatz NJ. Pseudotumor cerebri associated with corticosteroid withdrawal in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;117(3):352-357.

pubmed - Kelman SE, Heaps R, Wolf A, Elman MJ. Optic nerve decompression surgery improves visual function in patients with pseudotumor cerebri. Neurosurgery. 1992;30(3):391-395.

doi pubmed - Brourman ND, Spoor TC, Ramocki JM. Optic nerve sheath decompression for pseudotumor cerebri. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106(10):1378-1383.

doi pubmed - Eggenberger ER, Miller NR, Vitale S. Lumboperitoneal shunt for the treatment of pseudotumor cerebri. Neurology. 1996;46(6):1524-1530.

doi pubmed - Abu-Serieh B, Ghassempour K, Duprez T, Raftopoulos C. Stereotactic ventriculoperitoneal shunting for refractory idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(6):1039-1043; discussion 1043-1034.

- Dhungana S, Sharrack B, Woodroofe N. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Acta Neurol Scand. 2010;121(2):71-82.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.