| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 6, Number 11, November 2015, pages 508-511

Unusual Presentation of Streptococcus anginosus With Severe Sepsis, Liver Abscess Secondary to Biliary Tract Perforation

Ilknur Erdema, e, Mucahit Dogrub, Seyfi Emirc, Ridvan Kara Alia, Senay Elbasana, Reyhan Mutlud, Hayati Gunesd, Aynur Eren Topkayad

aDepartment of Infectious Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Namik Kemal University, Tekirdag, Turkey

bDepartment of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Namik Kemal University, Tekirdag, Turkey

cDepartment of General Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Namik Kemal University, Tekirdag, Turkey

dDepartment of Medical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Namik Kemal University, Tekirdag, Turkey

eCorresponding Author: Ilknur Erdem, Department of Infectious Disease, Faculty of Medicine, Namik Kemal University, Tekirdag, Turkey

Manuscript accepted for publication October 01, 2015

Short title: Unusual Presentation of S. anginosus

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14740/jmc2326w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Streptococcus anginosus (S. anginosus) is a member of the anginosus group of streptococci. They are part of the normal commensal flora of human mucous membranes and are infrequent pathogens. Infections range from minor oral infections to serious, complicated, life-threatening infections. They are commonly associated with abscess formation, and bacteremia is rare. We report here a case of severe sepsis with liver abscess secondary to biliary tract perforation caused by S. anginosus in a diabetic female patient.

Keywords: Streptococcus anginosus; Sepsis; Liver abscess; Biliary tract perforation

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The viridans streptococci (the α-hemolytic and non-hemolytic streptococci) are subdivided into five groups. The groups and the specific diseases associated with each group are: anginosus group, abscess formation; mitis group, septicemia in neutropenic patients and endocarditis; salivarius group, endocarditis; mutans group, dental caries; bovis group, bacteremia associated with cancer and meningitis. Anginosus group of streptococci comprises three distinct species: Streptococcus anginosus (S. anginosus), Streptococcus intermedius (S. intermedius), and Streptococcus constellatus (S. constellatus) [1]. These microorganisms are found in the oral cavity and in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract as part of the normal commensal flora. S. intermedius is more frequently found in dental plaque, whereas S. anginosus is more frequently found in the GI tract [2, 3]. Infections caused by these bacteria range from minor oral infections to serious, complicated, life-threatening infections. They are commonly associated with abscess formation, bacteremia is rare and mortality rate is low. Predisposing or underlying conditions are reported as previous surgery, trauma, diabetes, immunodeficiency and malignancy, but may also be related to poor oral hygiene or the patient’s overall health condition. S. anginosus was the most frequently isolated species from clinically significant specimens [3-8]. We report here an unusual presentation of S. anginosus with severe sepsis and liver abscess secondary to biliary tract perforation possibly due to cholelithiasis in a diabetic female patient. This case also emphasizes that early diagnosis and administration of appropriate antibiotic with surgical drainage are crucial to save live and to improve patient outcome.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 49-year-old female patient was admitted to our hospital, complaining of high fever, chills, sweating, headache, cough, nausea and arthralgia lasting for 1 week. She had previously been given gemifloxacin at another center. She was hospitalized with a presumptive diagnosis of sepsis with possible intra-abdominal origin and to research other possible etiologies of fever (including endocarditis, brucellosis). On her physical examination, body temperature was 40 °C, blood pressure was 110/60 mm Hg, pulse rate was 134 beats/min, respiratory rate was 30 breaths/min, and oxygen saturation was 99% while she was breathing ambient air on room air. Physical examination revealed right upper quadrant mild tenderness with no distension or rebound. The rest of examination was normal.

Initial hematologic and biochemical laboratory data were as follows: Hb, 12.3 g/dL; leucocytes, 20,300/mm3 with 85 % neutrophils; thrombocytes, 403,000/mm3; aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 82 IU/L (RR 0 - 32 IU/L); alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 41 IU/L (RR 0 - 35 IU/L); alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 315 IU/L (RR 35 - 114 IU/L); gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GTP), 86 IU/L (0 - 40 IU/L); albumin, 3.2 g/dL (RR 3.5 - 5.5 g/dL); total bilirubin, 1.317 mg/dL (RR 0 - 1.2 mg/dL); direct bilirubin, l.05 mg/dL (RR 0 - 0.3 mg/dL); sodium, 131 mmol/L (135 - 145 mmol/L); chloride, 91 mmol/L (RR 98 - 107 mmol/L); serum creatinine, 0.73 mg/dL (RR 0.5 - 1.2 mg/dL); ferritin, 901 ng/mL (RR 13 - 150 ng/mL); sedimentation rate, 107 mm/h; and C-reactive protein, 398 mg/L (RR 0 - 5 mg/L); D-dimer, 0.4 μg/mL (RR 0 - 0.5 μg/mL). Serology for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B and C, syphilis, Brucella, toxoplasmosis, cytomegalo virus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), Entamoeba histolytica and hydatid cyst is negative.

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed to exclude infective endocarditis at the same day. The transthoracic echocardiographic findings suggested that it may be due to infective endocarditis, and therefore, transesophageal echocardiography was recommended. The initial antibiotic regimen was intravenous meropenem (3 × 1 g/day), intravenous gentamicin (1 × 160 mg/day) and intravenous teicoplanin (1 × 800 mg/day maintenance dose following of 2 × 800 mg initial dose) for possible intra-abdominal sepsis and endocarditis after blood culture was obtained. Performed transesophageal echocardiogram finding after 1 week was negative for endocarditis.

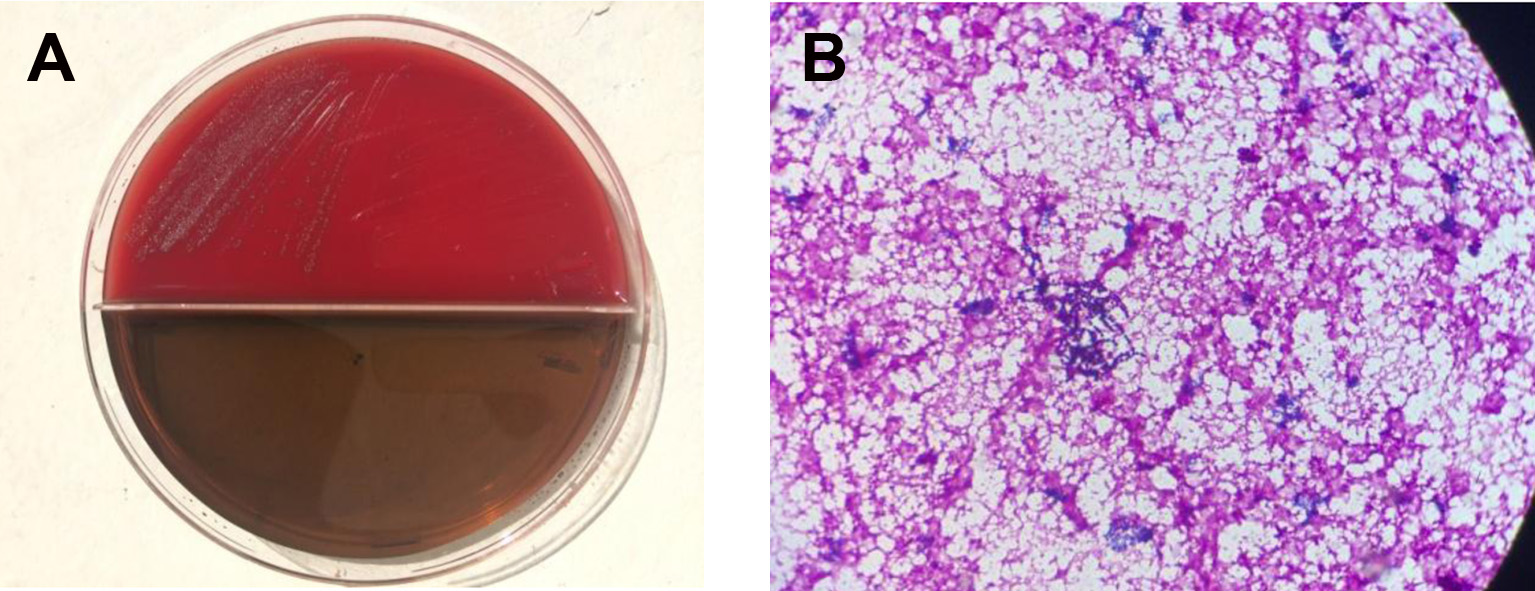

After 4 days of incubation, blood cultures taken on admission grew S. anginosus. According to the antimicrobial susceptibility results, it was sensitive to ampicillin, erythromycin, clindamycin, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, cefepime, imipenem, chloramphenicol and vancomycin, but resistant to penicillin and oxacillin. The identification of the S. anginosus at the species level was done using the BBL Crystal system. The susceptibility of the isolate was performed by the disk diffusion test. S. anginosus growth on blood agar was shown in Figure 1A, and gram stain of S. anginosus was shown in Figure 1B.

Click for large image | Figure 1. S. anginosus. (A) Colonies of S. anginosus on blood agar. (B) Gram stain of S. anginosus. |

The patient underwent an immediate radiologic evaluation. Hypoechoic areas in the liver were identified by the ultrasonography (USG). On the next day, abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed. The T2-weighted MR image reveals a nodule in the gallbladder lumen that may belong to calculi and a lesion at approximately 14 × 9 cm in size in the right lobe of the liver (Fig. 2A). Liver abscess with biliary tract perforation was shown in Figure 2B. It was reported that the described findings may be significant for liver abscess secondary to gallbladder perforation. The patient was consulted by general surgery and taken to exploratory laparotomy. Surgical drainage of abscess and a cholecystectomy were performed. S. anginosus was isolated from peritoneum and abscess cultures. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of all isolates that were obtained from blood, peritoneal fluid and abscess sample was same. The initial antibiotic regimen was meropenem, gentamicin and teicoplanin, but after infective endocarditis was excluded, this regimen was continued with meropenem only. She was discharged after 4 weeks of intravenous antibiotic therapy with cure. At 3 months, she remained well and repeated abdominal USG showed normal results.

Click for large image | Figure 2. MRI findings. (A) Axial T2-weighted fat-suppressed MRI showing calculi and hepatic abscess. (B) Coronal T2-weighted non-fat-suppressed image showing liver abscess with biliary tract perforation. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Members of the anginosus group are part of the normal flora of human mucous membranes and are infrequent significant pathogens. These species are catalase-negative gram-positive cocci, as the other members in the genus streptococcus. Colonies are typically < 0.5 mm in diameter after 24 h incubation and can be either beta- or alpha-hemolytic, although majority of them are alpha-hemolytic and are grouped to viridans group of streptococci. They are capable of causing a variety of multiple body site infections. They also tend to form abscesses and cause hematogenously disseminated infections [1, 2].

Bacteremia from the anginosus group is rare and usually the result of an identifiable focus of infection, such as intra-abdominal abscess, deep-seated head and neck infection, brain abscess and endocarditis. It is usually associated with underlying hepatic and biliary tract disease, neoplasia and diabetes. In the absence of endocarditis or distant focal suppurative complications, bacteremia has a good prognosis. Liver abscess and associated sepsis can be a serious and potentially life-threatening condition [2, 4, 9-12]. In one study about anginosus group of bacteremia cases, it was reported that 16 (55%) had intra-abdominal sepsis (liver abscess, cecal abscess, abdominal abscess, cholangitis/cholecystitis) [6]. In another study, members of the anginosus group were accounted 3-15% of streptococcal isolates from patients with endocarditis [3]. S. anginosus is the most frequently isolated species in bacteremic patients, while S. constellatus is infrequently isolated species [4-7, 10]. In our case, all blood cultures of S. anginosus were isolated. The liver abscess and biliary tract perforation limited by peritoneum were detected on the CT. There were no endocarditis findings shown by the transesophageal echocardiogram. She was diagnosed as S. anginosus sepsis with liver abscess secondary to biliary tract perforation due to cholelithiasis according to clinical, laboratory and radiological findings. At surgery the diagnosis of cholelithiasis with perforation and liver abscess was confirmed. Surgical drainage of abscess and cholecystectomy with exploratory laparotomy was performed by the general surgery. S. anginosus was isolated from culture of both peritoneal fluid and abscess specimens. Our patient’s extensive intra-abdominal disease process was considered that liver abscess is most likely as a complication of cholestasis due to gallstones. The presence of high fever and palpable right upper quadrant tenderness may indicate an acute onset.

Anginosus group organisms are generally susceptible to penicillin and other beta-lactam antibiotics. Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) to penicillin G are usually less than 0.125 μg/mL with occasional strains with MICs greater than 1.0 µg/mL. Penicillin resistance is rare [13-15]. According to a recent study, penicillin is proved to be an effective antimicrobial agent, with only five isolates (1.7%) showing penicillin resistance and 13 isolates (4.5%) showing intermediate resistance. Resistance to third-generation cephalosporins was approximately 2%, and approximately 1% of isolates showed intermediate resistance [16]. The recent increase in MICs to penicillin G suggests that initiation of penicillin G combined with gentamicin may be prudent. Alternatively, higher doses of penicillin or vancomycin could be used. Some authors suggest initial combination therapy with penicillin and an aminoglycoside because of the tolerance in some isolates. Subsequent therapy should be guided by the results of culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Clinically, infections caused by these bacteria have responded well to beta-lactams. Vancomycin and/or clindamycin have been alternative choice in case of beta-lactam allergies. Minimum 2 weeks of therapy (or more) should be administered in the setting of bacteremia. The longer therapy may be needed in case of liver abscess, according to the clinical response to the therapy. In addition to parenteral antimicrobial therapy, treatment of an abscess involves drainage of purulent material or surgical excision [2, 7]. In our case, S. anginosus strain was resistant to oxacillin. Therefore, meropenem therapy was continued. The patient was successfully treated by surgical drainage and administration of appropriate antibiotherapy.

Conclusion

Anginosus group often causes invasive pyogenic infections. Positive blood cultures, especially when multiple, should be evaluated for further investigation. It is also important to consider that successful treatment of these infections requires surgery and appropriate antibiotics. Antimicrobial therapy should be administered until clinical signs of infection have resolved.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

| References | ▴Top |

- Streptococcus. In: Patrick R. Murray, Ken S. Rosenthal, and Michael A. Pfaller (eds) .Medical Microbiology, 7th Edition. Mosby/Elsevier 2014, p. 118-214.

pubmed - Petti CA, Stratton CW. Streptococcus anginosus group. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R (Eds). Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 7th Ed, Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier, 2015, p.2362-2365.

- Whiley RA, Beighton D, Winstanley TG, Fraser HY, Hardie JM. Streptococcus intermedius, Streptococcus constellatus, and Streptococcus anginosus (the Streptococcus milleri group): association with different body sites and clinical infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(1):243-244.

pubmed - Bert F, Bariou-Lancelin M, Lambert-Zechovsky N. Clinical significance of bacteremia involving the "Streptococcus milleri" group: 51 cases and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(2):385-387.

doi pubmed - Claridge JE, 3rd, Attorri S, Musher DM, Hebert J, Dunbar S. Streptococcus intermedius, Streptococcus constellatus, and Streptococcus anginosus ("Streptococcus milleri group") are of different clinical importance and are not equally associated with abscess. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(10):1511-1515.

doi pubmed - Weightman NC, Barnham MR, Dove M. Streptococcus milleri group bacteraemia in North Yorkshire, England (1989-2000). Indian J Med Res. 2004;119(Suppl):164-167.

pubmed - Siegman-Igra Y, Azmon Y, Schwartz D. Milleri group streptococcus--a stepchild in the viridans family. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31(9):2453-2459.

doi pubmed - Giuliano S, Rubini G, Conte A, Goldoni P, Falcone M, Vena A, Venditti M, et al. Streptococcus anginosus group disseminated infection: case report and review of literature. Infez Med. 2012;20(3):145-154.

pubmed - Salavert M, Gomez L, Rodriguez-Carballeira M, Xercavins M, Freixas N, Garau J. Seven-year review of bacteremia caused by Streptococcus milleri and other viridans streptococci. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15(5):365-371.

doi pubmed - Jacobs JA, Pietersen HG, Stobberingh EE, Soeters PB. Bacteremia involving the "Streptococcus milleri" group: analysis of 19 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19(4):704-713.

doi pubmed - Singh KP, Morris A, Lang SD, MacCulloch DM, Bremner DA. Clinically significant Streptococcus anginosus (Streptococcus milleri) infections: a review of 186 cases. N Z Med J. 1988;101(859):813-816.

pubmed - Junckerstorff RK, Robinson JO, Murray RJ. Invasive Streptococcus anginosus group infection-does the species predict the outcome? Int J Infect Dis. 2014;18:38-40.

doi pubmed - Limia A, Jimenez ML, Alarcon T, Lopez-Brea M. Five-year analysis of antimicrobial susceptibility of the Streptococcus milleri group. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18(6):440-444.

doi pubmed - Tracy M, Wanahita A, Shuhatovich Y, Goldsmith EA, Clarridge JE, 3rd, Musher DM. Antibiotic susceptibilities of genetically characterized Streptococcus milleri group strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(5):1511-1514.

doi pubmed - Bantar C, Fernandez Canigia L, Relloso S, Lanza A, Bianchini H, Smayevsky J. Species belonging to the "Streptococcus milleri" group: antimicrobial susceptibility and comparative prevalence in significant clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34(8):2020-2022.

pubmed - Chun S, Huh HJ, Lee NY. Species-specific difference in antimicrobial susceptibility among viridans group streptococci. Ann Lab Med. 2015;35(2):205-211.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.