| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 8, Number 11, November 2017, pages 347-350

A Rare Skin Manifestation in a Patient With Human Immunodeficiency Virus: A Case Report and Review of the Literature

Nabil Braiteha, Abraham Tareq Yacouba, Sama Alchalabia, Rosa Solisa, Neha Kumarb, Christine Fenlonc, d

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, Wilson Medical Center, United Health Services Hospitals, 33-57 Harrison Street, Johnson City, NY 13907, USA

bDepartment of Pharmacy Medicine, Wilson Medical Center, United Health Services Hospitals, 33-57 Harrison Street, Johnson City, NY 13907, USA

cDepartment of Infectious Disease and Internal Medicine, Wilson Medical Center, United Health Services Hospitals, 33-57 Harrison Street, Johnson City, NY 13907, USA

dCorresponding Author: Christine Fenlon, Department of Infectious Disease and Internal Medicine, Wilson Medical Center, United Health Services Hospitals, 33-57 Harrison Street, Johnson City, NY 13907, USA

Manuscript submitted March 12, 2017, accepted April 5, 2017

Short title: Skin Manifestation in HIV

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc2799w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in association with autoimmune bullous disease is a very rare entity, and the pathophysiology remains uncertain. We present a case of a 65-year-old African-American female with HIV who developed a single skin lesion on her face. Subsequently, she developed multiple blistering skin lesions throughout her body. Skin biopsy of the blistering lesions revealed bullous pemphigoid.

Keywords: Bullous pemphigoid; Human immunodeficiency virus; Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Cutaneous disorders related to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection are vast, and often the skin is the first and only organ affected during most of the course of HIV disease [1]. Autoimmune blistering diseases are rare in patients with HIV [2]. Bullous pemphigoid is the most common autoimmune blistering disease of the skin and mucous membranes and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality [3, 4].

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 65-year-old African-American female with a past medical history of intravenous drug use and HIV was evaluated in the emergency department for diffuse, erythematous, and hemorrhagic skin lesions throughout her body. She denied any fever, chills, sweats, malaise, nausea, vomiting, or loss of appetite. Two months prior to her emergency department presentation, she noted a single 1.0 × 0.5 cm eczematous and papular lesion located over the left infra-orbital triangle of the face. The following day, she was evaluated by her primary care physician and was treated with a 2-week course of topical silver sulfadiazine cream. The facial lesion did not respond to the treatment, and the patient subsequently developed new lesions on the contralateral side of her face as well as her chest, upper and lower extremities, trunk, and back.

Her past medical history was significant for hypothyroidism, depression, and tonic-clonic seizures secondary to posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). She consumes alcohol and resides in a nursing home. Her home medications include atazanavir 300 mg once daily, emtricitabine 200 mg once daily, ritonavir 100 mg once daily, tenofovir 300 mg once daily, levothyroxine 25 µg once daily, paroxetine 20 mg once daily, and levetiracetam 1,000 mg twice daily. She was compliant with her antiepileptic medication.

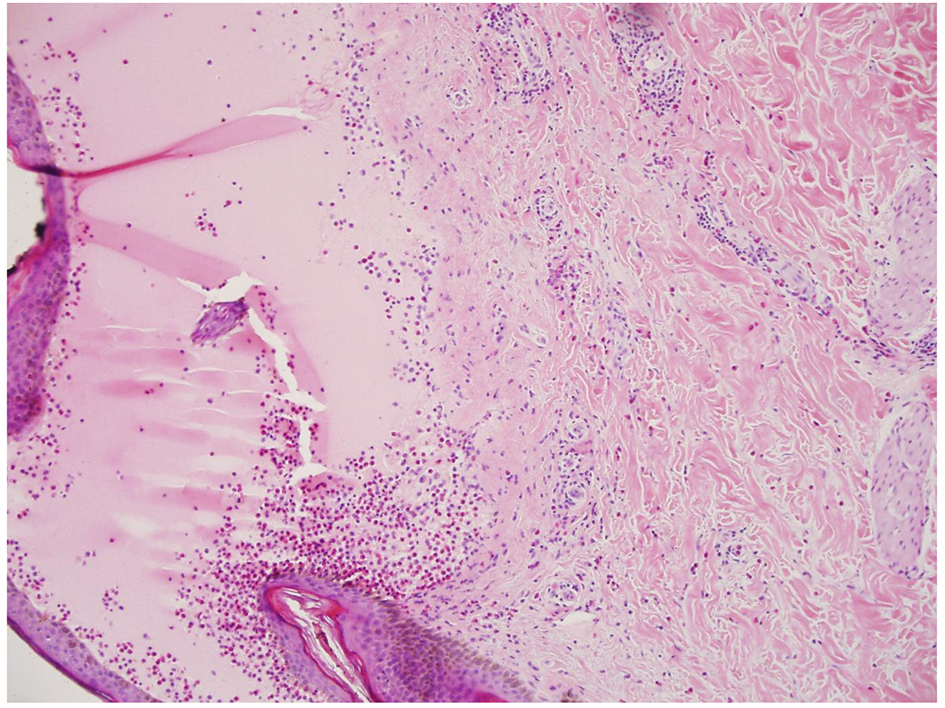

In the emergency department, her physical examination was unremarkable except for 1.0 × 3.0 cm tense bullae on an erythematous and urticarial base and blisters that are numerous and widespread throughout her face, torso, back, and upper and lower extremities (Figs. 1 and 2). Laboratory workup revealed a white blood cell count of 5,200/mm3, hemoglobin of 8.2 g/dL, and platelets of 108,000/mm3. Chemistry panel revealed sodium of 139 mmol/L, potassium of 3.9 mmol/L, BUN of 24 mg/dL, and creatinine of 1.3 mg/dL. Liver function tests were within normal limits. The epidermal antibodies titer was positive with a ratio of 1:80. A skin biopsy was performed and was consistent with bullous pemphigoid (Fig. 3). This was confirmed by direct immunofluorescence testing.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Tense, clear fluid-filled vesicles and blisters over normal and erythematous skin of the right upper extremity. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Tense, clear fluid-filled vesicles and blisters over normal and erythematous skin of the trunk along with dried areas of healing skin. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Hematoxylin-eosin stain (× 10). Subepidermal bullae containing eosinophils and polymorphs. The dermis shows perivascular infiltrates containing neutrophils and eosinophils. |

The patient was admitted and treated with intravenous (IV) vancomycin 1.0 g every 12 h, IV doxycycline 100 mg every 12 h, and oral prednisone 50 mg daily. After 1 week, her symptoms began to slowly improve (Fig. 4).

Click for large image | Figure 4. Healing skin lesions that were fluid-filled vesicles and blisters over the trunk and upper extremity 1 week after treatment. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) belongs to the group of autoimmune subepidermal blistering diseases, which are characterized by an autoantibody response directed against distinct components of the dermoepidermal junction of skin and adjacent mucous membranes [5].

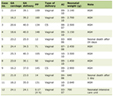

BP may present with different clinical presentations, and the onset may be either subacute or acute. The characteristic skin lesion is usually a large, tense blister arising on an erythematous base. The bullae are usually filled with clear fluid but may be hemorrhagic. Pruritus is frequently present [6]. BP in the HIV population is rare. In the review of literature, there were three cases reported; however, only two were confirmed (Table 1 [7-9]).

Click to view | Table 1. Bullous Pemphigoid Cases in Association With HIV Infection |

The pathophysiology of autoimmune bullous diseases in the HIV population remains uncertain. The reported cases in Table 1 reveal that patients with HIV are able to mount organ-specific autoantibody mediated disease. One possible explanation is that immune dysregulation in the HIV population may lead to higher risk of developing an autoimmune disease [7, 10, 11].

Bullous pemphigoid antibodies (Bpab) were detected in the HIV population with chronic pruritis or prurigo diseases. One interesting study conducted by Kinloch-de Loes and colleagues revealed that there is an increased incidence of Bpab as HIV progressed from stage 2 to stage 4 in patients with chronic pruritis or prurigo diseases [12, 13].

Our patient had a positive epidermal antibody titer with no chronic skin diseases reported. Further studies are necessary to determine if the presence of circulating Bpab is a risk factor for the development of BP in HIV-infected patients with no chronic skin diseases.

Adverse cutaneous reactions to medications occur more commonly in the later stages of HIV disease [14]. Karadag and colleagues reported a case of a 70-year-old female who developed BP 1 month after starting to use levetiracetam [15]. Our patient was treated with levetiracetam for the past 6 months before presenting with skin blisters. Her skin manifestations resolved slowly despite the continuation of levetiracetam.

Treatment of BP in HIV is challenging. The main treatments are corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents (e.g., azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate) [16, 17]. These agents may cause a rapid progression of HIV; however, a short course of corticosteroids appears to be safe [7, 17]. Once BP has improved clinically with no new blisters as well as a reduction in inflammation and pruritus, a careful tapering of the prednisone over approximately 4 months can be initiated according to the clinical response of the patient [18].

Conclusion

HIV in association with autoimmune bullous disease is a very rare entity. The pathophysiology of bullous disease in HIV-infected patients remains uncertain. It is important for clinicians to keep BP in the differential diagnosis in HIV patients presenting with blistering skin diseases.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Funding

None.

| References | ▴Top |

- Singh H, Singh P, Tiwari P, Dey V, Dulhani N, Singh A. Dermatological manifestations in HIV-infected patients at a tertiary care hospital in a tribal (Bastar) region of Chhattisgarh, India. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54(4):338-341.

doi pubmed - Demathe A, Arede LT, Miyahara GI. Mucous membrane pemphigoid in HIV patient: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1(1):345.

doi pubmed - Feliciani C, Joly P, Jonkman MF, Zambruno G, Zillikens D, Ioannides D, Kowalewski C, et al. Management of bullous pemphigoid: the European Dermatology Forum consensus in collaboration with the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(4):867-877.

doi pubmed - Singh S. Evidence-based treatments for pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and bullous pemphigoid: a systematic review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77(4):456-469.

doi pubmed - Korman N. Bullous pemphigoid. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(5 Pt 1):907-924.

doi - Khandpur S, Verma P. Bullous pemphigoid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77(4):450-455.

doi pubmed - De D, Kanwar AJ, Radotra BD, Narang T. Bullous eruption in a patient infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Skinmed. 2008;7(2):98-101.

doi pubmed - Bull RH, Fallowfield ME, Marsden RA. Autoimmune blistering diseases associated with HIV infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(1):47-50.

doi pubmed - Levy PM, Balavoine JF, Salomon D, Merot Y, Saurat JH. Ritodrine-responsive bullous pemphigoid in a patient with AIDS-related complex. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114(5):635-636.

doi pubmed - Kopelman RG, Zolla-Pazner S. Association of human immunodeficiency virus infection and autoimmune phenomena. Am J Med. 1988;84(1):82-88.

doi - Lane HC, Masur H, Edgar LC, Whalen G, Rook AH, Fauci AS. Abnormalities of B-cell activation and immunoregulation in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1983;309(8):453-458.

doi pubmed - Kinloch-de Loes S, Didierjean L, Rieckhoff-Cantoni L, Imhof K, Perrin L, Saurat JH. Bullous pemphigoid autoantibodies, HIV-1 infection and pruritic papular eruption. AIDS. 1991;5(4):451-454.

doi pubmed - Mueller S, Klaus-Kovtun V, Stanley JR. A 230-kD basic protein is the major bullous pemphigoid antigen. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;92(1):33-38.

doi pubmed - Gordin FM, Simon GL, Wofsy CB, et al. Adverse reactions to trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100(4):494-499.

doi - Karadag AS, Bilgili SG, Calka O, Onder S, Kosem M, Burakgazi-Dalkilic E. A case of levetiracetam induced bullous pemphigoid. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32(2):176-178.

doi pubmed - Patton T, Korman N. Role of methotrexate in the treatment of bullous pemphigoid in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(8):623-629.

doi pubmed - McComsey GA, Whalen CC, Mawhorter SD, Asaad R, Valdez H, Patki AH, Klaumunzner J, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of prednisone in advanced HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2001;15(3):321-327.

doi pubmed - Mutasim DF. Therapy of autoimmune bullous diseases. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3(1):29-40.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.