| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 9, Number 11, November 2018, pages 375-378

Anomalous Right Coronary Artery With Malignant Course

Ahmad Hasana, c, Fahar Adnanb, Shahzad Shoukata, Umer Aftaba, Muhammad Waqasa, Muhammad Iqbala

aDepartment of Cardiology, Allama Iqbal Medical College/Jinnah Hospital, Allama Shabbir Usmani Road, Faisal Town, Lahore, Pakistan

bDepartment of Cardiology, Multan Institute of Cardiology, Multan, Pakistan

cCorresponding Author: Ahmad Hasan, 25-C Jinnah Hospital Residential Colony Opposite Jinnah Hospital, Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan

Manuscript submitted October 4, 2018, accepted October 12, 2018

Short title: Anomalous Right Coronary Artery

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3183

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Anomalous right coronary artery origin from contralateral sinus is a rare but lethal variant that may mimic like acute coronary syndrome and is a potential cause of sudden cardiac death. This needs early diagnosis with prompt treatment which may be conservative or interventional depending upon the exact anatomy and route of the vessel. Here we present a unique case of combination of anomalous right coronary artery origin from opposite sinus causing ischemia, with left ventricle (LV) non-compaction ending in non-hemorrhagic stroke.

Keywords: Anomalous coronary artery; Inter-arterial course; Computed angiography

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Coronary artery anomalies are very rare disorders, accounting for only 1.3% of the patients, undergoing diagnostic investigations. In Yamanaka’s report, right coronary artery (RCA) arising from the left coronary cusp was noted in 0.17% of coronary angiographies, while left coronary artery (LCA) from the right coronary cusp was seen in 0.047% [1].

We report a case of aberrant origin of RCA having a malignant course causing ischemia, left ventricle (LV) showing apical non-compaction as well and later on developing ischemic stroke. This course of the disease, to best of our knowledge, has never been reported in literature before.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

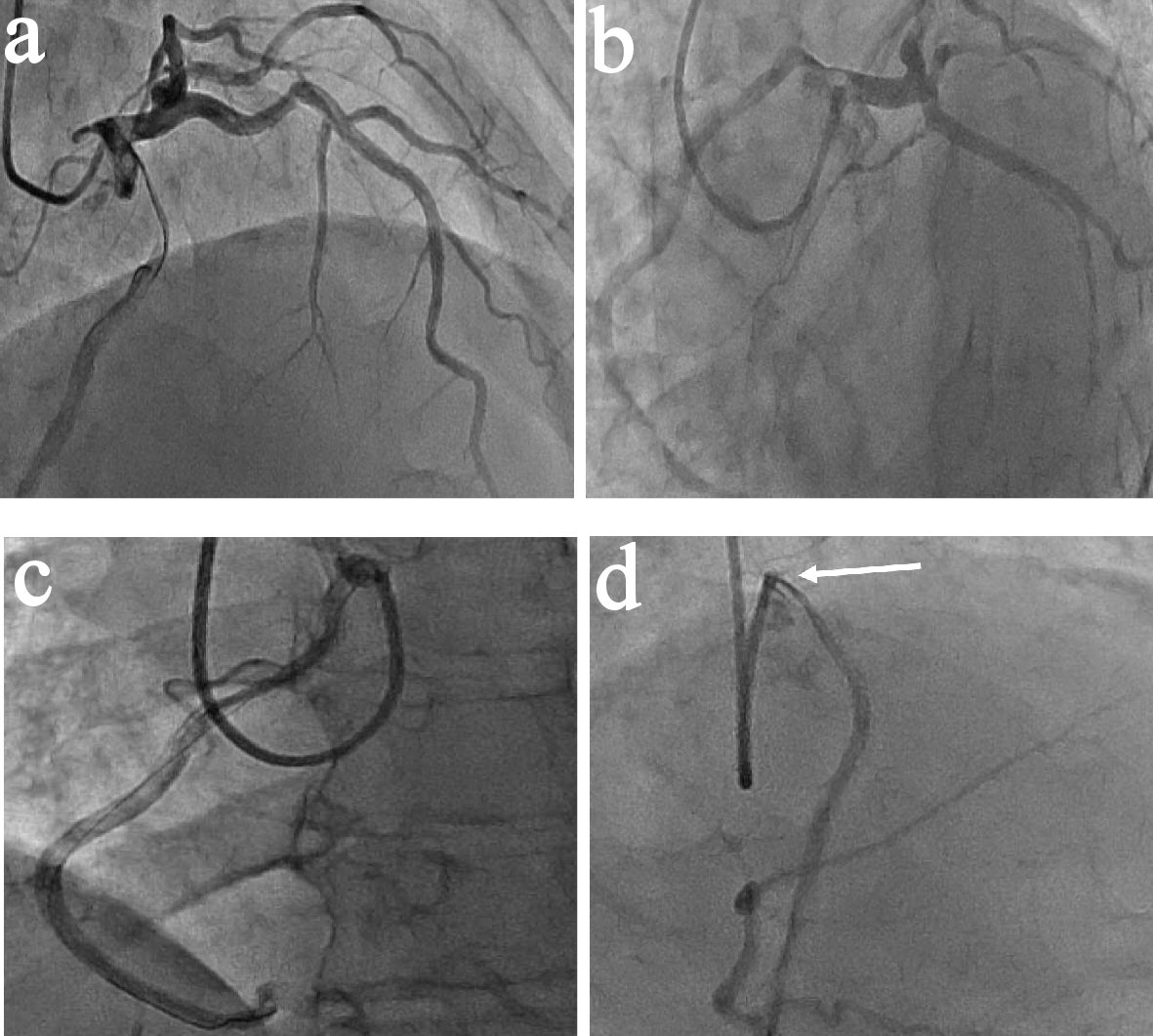

A 57 years old man, diabetic and hypertensive, presented with chest pain of 4 days duration. The pain was of ischemic in nature. Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed ST-T changes in inferior leads. He was managed on the lines of Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) and coronary angiography (CA) was planned. The left main (LM) was normal with mild irregularities in left anterior descending artery (LAD) and normal non-dominant left circumflex (LCX). Surprisingly the injection in left system showed an aberrant vessel originating from the left cusp which was anomalous right coronary artery (ARCA). This was then selectively engaged with the help of XB guide and a BMW wire showing a mega dominant RCA with moderate ostial stenosis (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Coronary angiography. (a) RAO cranial view. (b) LAO caudal view. LM injection showing LAD and LCX with ARCA arising from left coronary cusp (LCC). (c) LAO view showing selective engagement of anomalous right coronary artery arising from LCC engaged with XB guide. (d) RAO view showing moderate ostial stenosis (arrow). |

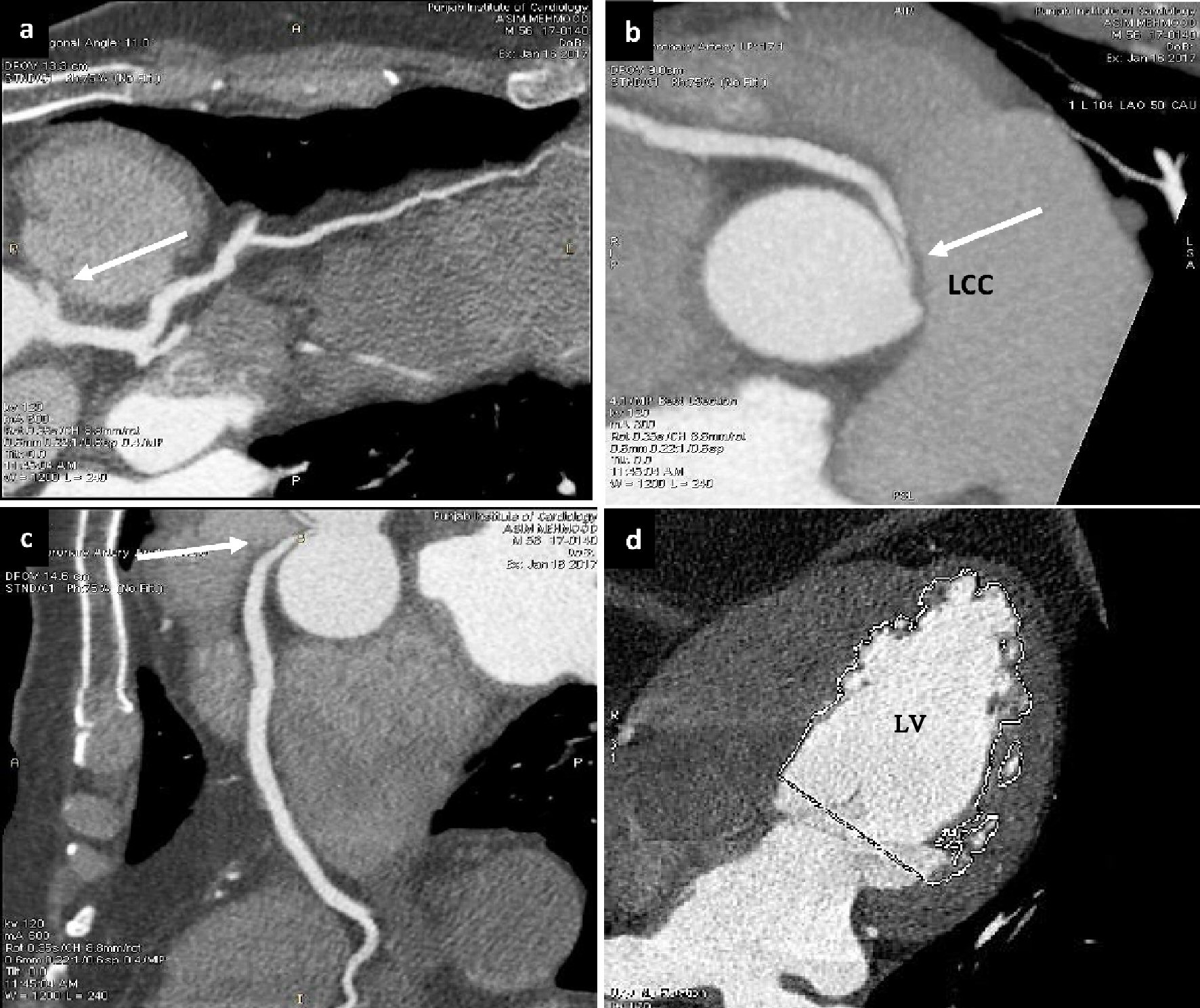

Multi-detector computed tomography angiography (MDCT) was done then to rule out the inter-arterial course of the vessel, which confirmed it (Fig. 2a-c). The LV function was depressed, with ejection fraction (EF) 39% showing mid apical non-compaction (Fig. 2d).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Multi-detector computed tomography angiography. (a), (b) and (c) Showing aberrant origin of RCA from LCC (white arrows). (d) Showing non-compaction of LV. |

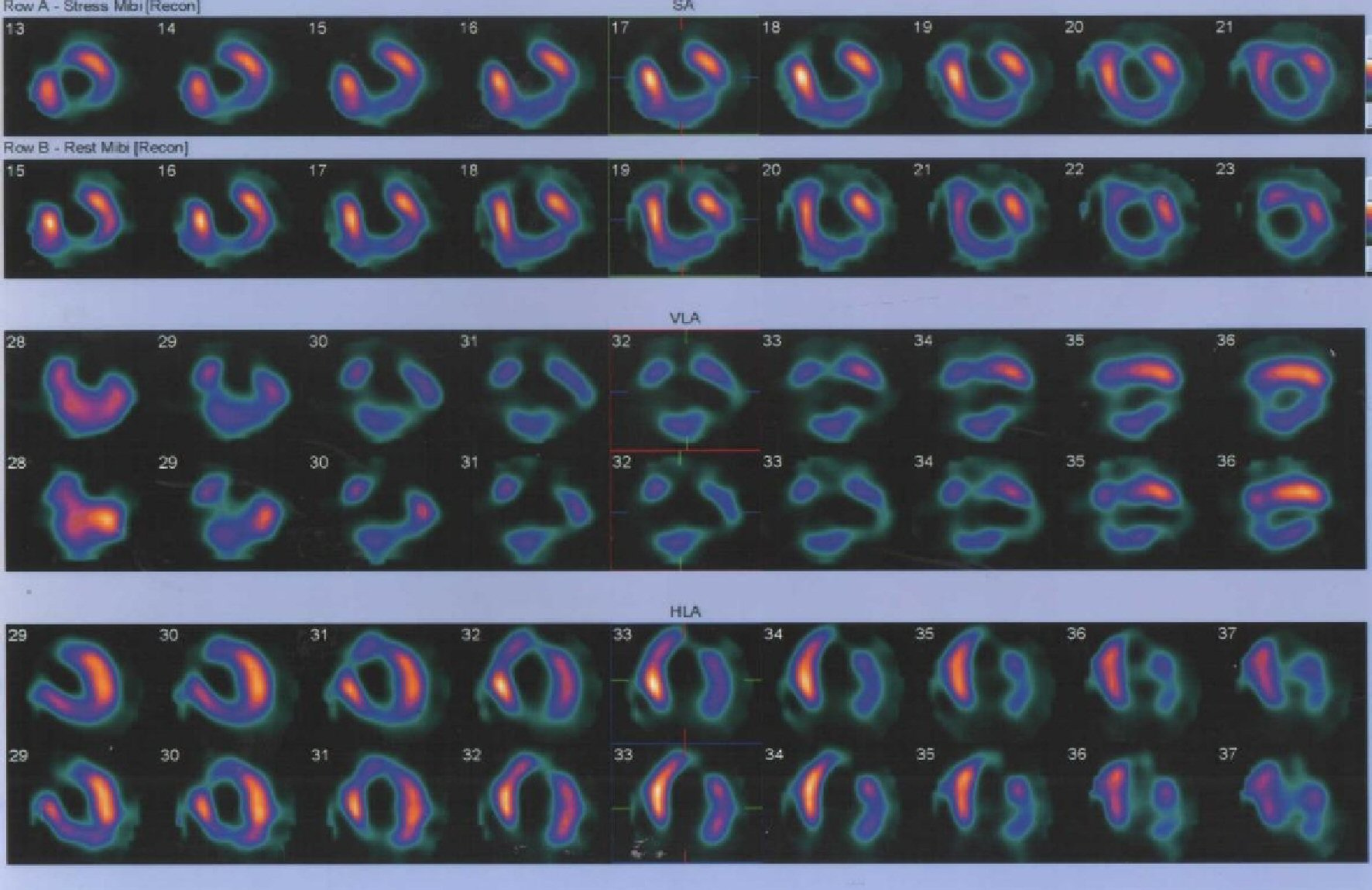

He was referred to cardiac surgeon for surgery who advised stress test. Stress test (Fig. 3) showed dilated LV with segmental myocardial infarctions (MI) involving apex, apical 1/2 of inferior wall, apical septum, mid anterior wall and apical lateral wall. Partial thickness MI of basal inferior wall, infero-lateral part, basal and apical segments of anterior wall and reduced EF were found.

Click for large image | Figure 3. Stress test showing ischemic changes in inferior, lateral, apical and mid anterior wall of left ventricle. |

He was then planned to undergo coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), as evidence of ischemia was there and the patient was still complaining of ischemic pain. His bilateral carotid Doppler was normal. The patient, while waiting for surgery, developed non-hemorrhagic stroke and right sided body weakness. His immediate computed tomography (CT) scan of brain was unremarkable but after 48 h, it showed a large infarct with hemorrhagic transformation within it. He needed ventilator support, was shifted back to the ward after 1 week, followed by discharge in a stable condition. The CABG was subsequently deferred and the patient is currently being managed on intensive medical therapy.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Anomalous coronary artery from the opposite sinus is a very rare condition reported to be 1.3% by Yamanaka’s report [1] and 1.07% in P. Angelini’s group study respectively [2].

This anomalous origin mainly involves RCA, as a study shown by Garg that, 15 out of 4,100 patients (0.37%) had abnormal origin of RCA from the left sinus of Valsalva, but only one patient (0.02%) had LCA from the right sinus [3]. Although its prevalence is low, but the consequences can be dire ranging from myocardial ischemia to syncope and arrhythmias; but the most dreadful condition that it leads to is sudden cardiac death [4]. In an autopsy report, the mortality percentage of anomalous RCA arising from left sinus was found to be 57% as compared to be 25% of the anomalous vessel arising from right sinus [5].

The condition may have severe consequences, so its diagnosis should be made accurately. There are several methods to evaluate ARCA including echocardiography (ECHO), angiography, MDCT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Transthoracic ECHO is poor in diagnosing this anomaly but transesophageal ECHO provides much better information [6]. Non-invasive tools like MDCT [7] and MRI [8] are investigations of choice. When MDCT is combined with stress myocardial perfusion scan, the yield of diagnosing the anomaly gets much enhanced [7, 9].

The LV function, shown by both MDCT and stress test was depressed confirming obstruction at some part in the RCA causing infarction. There have been proposed many mechanisms of causation of ischemia in this type of vessel like, slit like RCA ostium in aortic wall, acute angulation of the vessel, unusual angle of take-off, tortuous proximal vessel leading to extended atherosclerotic process and lipid accumulation [10, 11]. In our case, the vessel was taking interarterial course, i.e. between aorta and pulmonary artery and the pulsations of these big vessels may render that critical part of RCA to episodic occlusion causing ischemia as well as the moderate ostial lesion.

The incidence of stroke after myocardial infarction (MI) is high. A study, by Witt and colleagues in 2005 [12] showed a 44-fold rise within 30 days after MI; and even after 3 years it remained two to three times high. Another study showed a short-term incidence of 3.0 to 5.2 percent of stroke [13] while the 5-year incidence was shown to be 8.1 percent [14]. Although the incidence of stroke is more in anterior wall MI but the major determinant for thrombus formation leading to embolic stroke is the low ejection fraction [14], severe apical-wall-motion abnormality [15] as its absence in both anterior and inferior infarction makes the patient a low risk for stroke. Our patient had both the low ejection fraction and apical wall motion abnormality, so it’s a strong suspicion that he formed a thrombus in left ventricle which later embolized the vessels leading to stroke. Another possibility is that our patient was diagnosed having apical non-compaction which is a potential cause for systolic embolic events [16].

The prevalence of non-compaction of LV in adults is only about 0.014% [17] but more recent studies have found its increase prevalence to about 0.25 to 5 % in varying populations [18]. The occurrence of aberrant RCA with LV non-compaction has not yet been reported in literature to our knowledge, so it’s a unique case.

Revascularization in the form of CABG is recommended (class IA) for documented coronary ischemia in the setting of an anomalous RCA coursing between aorta and pulmonary arteries by American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines for congenital heart diseases [19].

Conclusions

This is a rare case of association of anomalous RCA from left coronary cusp (LCC) with apical non-compaction of LV. The condition may remain asymptomatic but it can lead to devastating conditions like myocardial ischemia, syncope and even sudden cardiac death, so proper and urgent evaluation followed by swift management is needed.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Declaration

The research work was generated from Allama Iqbal Medical College/Jinnah Hospital, Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan. We solemnly declare that no grants, contracts or any sort of financial support were provided by any institute or foundation.

| References | ▴Top |

- Yamanaka O, Hobbs RE. Coronary artery anomalies in 126,595 patients undergoing coronary arteriography. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1990;21(1):28-40.

doi pubmed - Angelini P, Villason S, Chan AV, Diez G. Coronary artery anomalies: a comprehensive approach. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia (PA). 1999.

- Garg N, Tewari S, Kapoor A, Gupta DK, Sinha N. Primary congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries: a coronary: arteriographic study. Int J Cardiol. 2000;74(1):39-46.

doi - Penalver JM, Mosca RS, Weitz D, Phoon CK. Anomalous aortic origin of coronary arteries from the opposite sinus: a critical appraisal of risk. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2012;12:83.

doi pubmed - Taylor AJ, Rogan KM, Virmani R. Sudden cardiac death associated with isolated congenital coronary artery anomalies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20(3):640-647.

doi - Cha KS, Kim HK, Cun KJ, et al. Role of transesophageal echocardiography in indentifying anomalous origin and course of coronary arteries. Korean Circ J. 1998;28:576-585.

doi - Datta J, White CS, Gilkeson RC, Meyer CA, Kansal S, Jani ML, Arildsen RC, et al. Anomalous coronary arteries in adults: depiction at multi-detector row CT angiography. Radiology. 2005;235(3):812-818.

doi pubmed - Lee J, Choe YH, Kim HJ, Park JE. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstration of anomalous origin of the right coronary artery from the left coronary sinus associated with acute myocardial infarction. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27(2):289-291.

doi pubmed - Cohenpour M, Tourovski A, Zyssman I, Friedensohn A, Gayer G, Horne T. Anomalous origin of left main coronary artery: the value of myocardial scintigraphic and spiral computed tomography scans. Nucl Med Rev Cent East Eur. 2006;9(1):69-71.

pubmed - Hutchins GM, Miner MM, Boitnott JK. Vessel caliber and branch-angle of human coronary artery branch-points. Circ Res. 1976;38(6):572-576.

doi pubmed - Laurence L, Thurman R, Bruce TC. Atherosclerotic occlusions in anomalous left circumflex coronary arteries. A report of two unusual cases & a review of pertinent literature. Paroi Arterielle. 1975;3(2):55-59.

pubmed - Witt BJ, Brown RD, Jr., Jacobsen SJ, Weston SA, Yawn BP, Roger VL. A community-based study of stroke incidence after myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(11):785-792.

doi pubmed - Martin R, Bogousslavsky J. Mechanism of late stroke after myocardial infarct: the Lausanne Stroke Registry. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56(7):760-764.

doi pubmed - Loh E, Sutton MS, Wun CC, Rouleau JL, Flaker GC, Gottlieb SS, Lamas GA, et al. Ventricular dysfunction and the risk of stroke after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(4):251-257.

doi pubmed - Asinger RW, Mikell FL, Elsperger J, Hodges M. Incidence of left-ventricular thrombosis after acute transmural myocardial infarction. Serial evaluation by two-dimensional echocardiography. N Engl J Med. 1981;305(6):297-302.

doi pubmed - Ritter M, Oechslin E, Sutsch G, Attenhofer C, Schneider J, Jenni R. Isolated noncompaction of the myocardium in adults. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72(1):26-31.

doi pubmed - Oechslin EN, Attenhofer Jost CH, Rojas JR, Kaufmann PA, Jenni R. Long-term follow-up of 34 adults with isolated left ventricular noncompaction: a distinct cardiomyopathy with poor prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(2):493-500.

doi - Belanger AR, Miller MA, Donthireddi UR, Najovits AJ, Goldman ME. New classification scheme of left ventricular noncompaction and correlation with ventricular performance. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102(1):92-96.

doi pubmed - Warnes CA, Williams RG, Bashore TM, Child JS, Connolly HM, Dearani JA, Del Nido P, et al. ACC/AHA 2008 guidelines for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines on the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease). Developed in Collaboration With the American Society of Echocardiography, Heart Rhythm Society, International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(23):e143-e263.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.