| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 13, Number 2, February 2022, pages 66-70

Rare Presentation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Mimicking Prostate Cancer

Seyed Mohammad Nahidia, d , Harman Singhb, Sharang Tickooa, Leonidha Dukac, Jung Wonc, Jennifer Gulasc

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, St George’s University, Grenada

bDepartment of Internal Medicine, Medical University of the Americas, Charlestown, Nevis

cDepartment of Internal Medicine, Wyckoff Heights Medical Center, Brooklyn, New York, USA

dCorresponding Author: Seyed Mohammad Nahidi, Department of Internal Medicine, Wyckoff Heights Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY 11237, USA

Manuscript submitted November 30, 2021, accepted January 18, 2022, published online February 16, 2022

Short title: M. tuberculosis Mimicking Prostate Cancer

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3855

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is primarily known to affect the lungs with cavitary lesions and enlarged lymph nodes as the first telltale sign. However, if the bacteria spread to extrapulmonary areas such as the bones, and lack lymphadenopathy, then the differential diagnosis may become misleading. We present a case of a 68-year-old male patient with a chief complaint of chronic left hip pain upon which computer tomography identified lytic lesions on the left hip. Given the mildly elevated prostate-specific antigen with a family history of prostate cancer, a bone biopsy was warranted. The biopsy revealed non-caseating granulomas and the DNA probe identified the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. This case signifies that atypical presentations of Mycobacterium tuberculosis may mimic other diagnoses and more invasive techniques such as a biopsy may be necessary.

Keywords: Atypical Mycobacterium tuberculosis; Mimicking prostate cancer; Osteoarticular tuberculosis; DNA probe biopsy; Non-necrotizing granuloma

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Tuberculosis (TB) is a mycobacterial infection that commonly infects the lungs and causes a myriad of pulmonary symptoms [1]. However, although rare, Mycobacterium tuberculosis can infect the bones and joints, also known as osteoarticular tuberculosis (OATB). The bone that is most commonly affected is the vertebrae [1]. The symptoms of OATB and metastatic prostate cancer can overlap and are hard to differentiate without further investigation.

The preference of OA tuberculosis to arise in the spine and large joints can be attributed to their extensive vascular supply. The bacilli travel from the lung to the spine via the Batson paravertebral venous plexus [2, 3]. Granulomatous erosion of the disc space causes narrowing of the spine. Sacroiliac tuberculosis however, is more frequently missed due to its vague symptoms and inaccessibility to the joint. It can further be complicated in its presentation similarity to metastatic cancer. As a result, sacroiliac TB is commonly misdiagnosed in endemic areas, with fever and nonspecific pain over the sacroiliac joint being the most common symptoms.

The case was a 68-year-old male patient who presented with progressively worsening hip pain and a travel history to the Dominican Republic, where there was a high incidence of TB [3]. In this case, a detailed history was imperative when forming a differential diagnosis. A positive family history for prostatic cancer, mildly elevated prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels and lesions on the computer tomography (CT) scan initially misled the differential diagnosis towards metastatic prostate cancer. However, a DNA probe of the hip biopsy revealed Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 68-year-old male patient, with a past medical history significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, cerebral vascular attack, coronary artery disease, status-post pacemaker, and chronic left hip pain for 35 years, was referred to our institution’s emergency department by an orthopedic clinic for further evaluation for his progressively worsening chronic left hip pain. The patient’s family history was significant for paternal prostate cancer. The patient used crutches as he was unable to ambulate without assistance due to severe left hip pain. He claimed the pain worsened 5 months ago after he returned from the Dominican Republic, which he frequented. He stated that the pain initially was located on his left middle thigh and after 2 months it migrated to his hip which exacerbated his chronic hip pain. He described the pain as persistent aching and throbbing. He denied any other associated symptoms.

Diagnosis

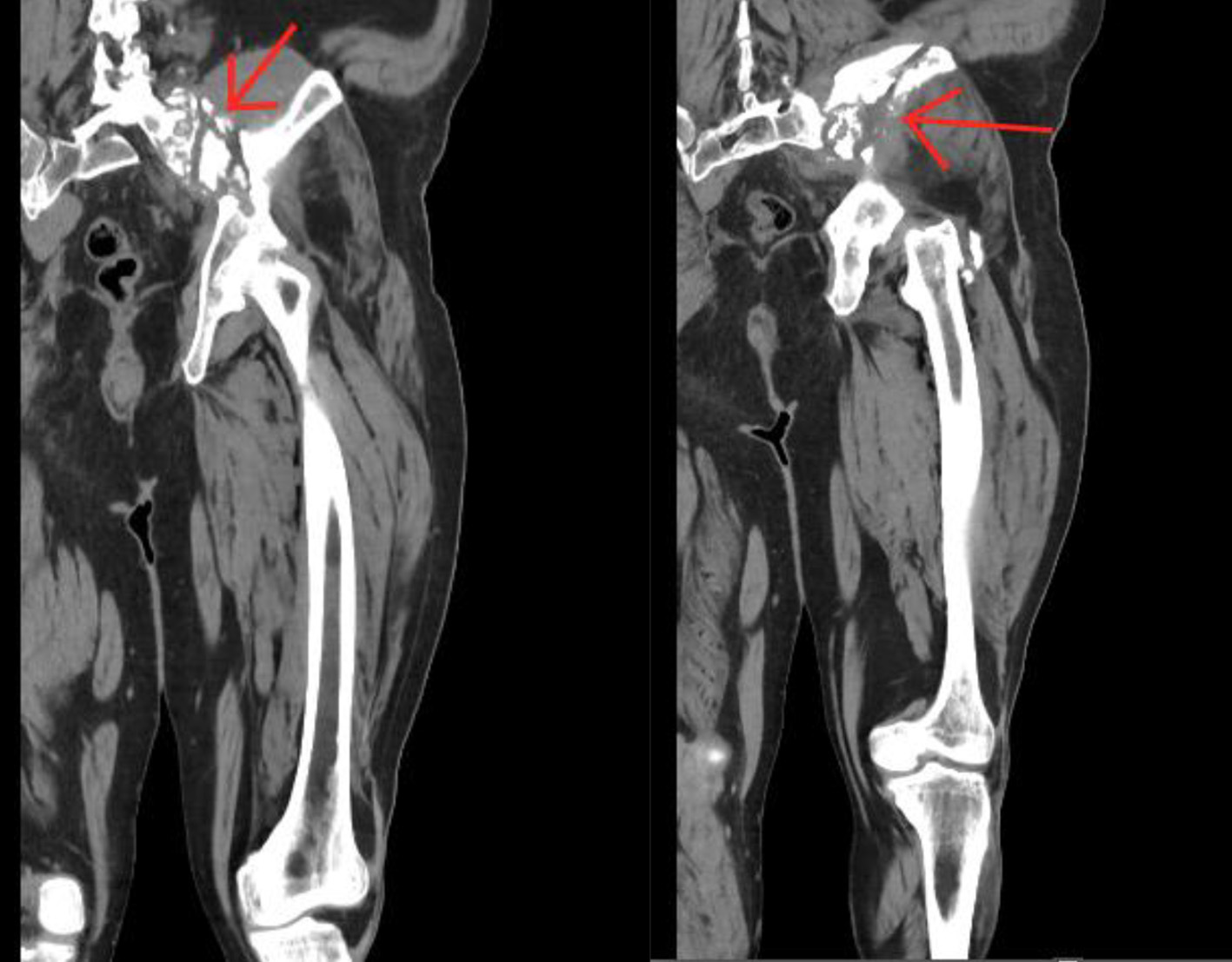

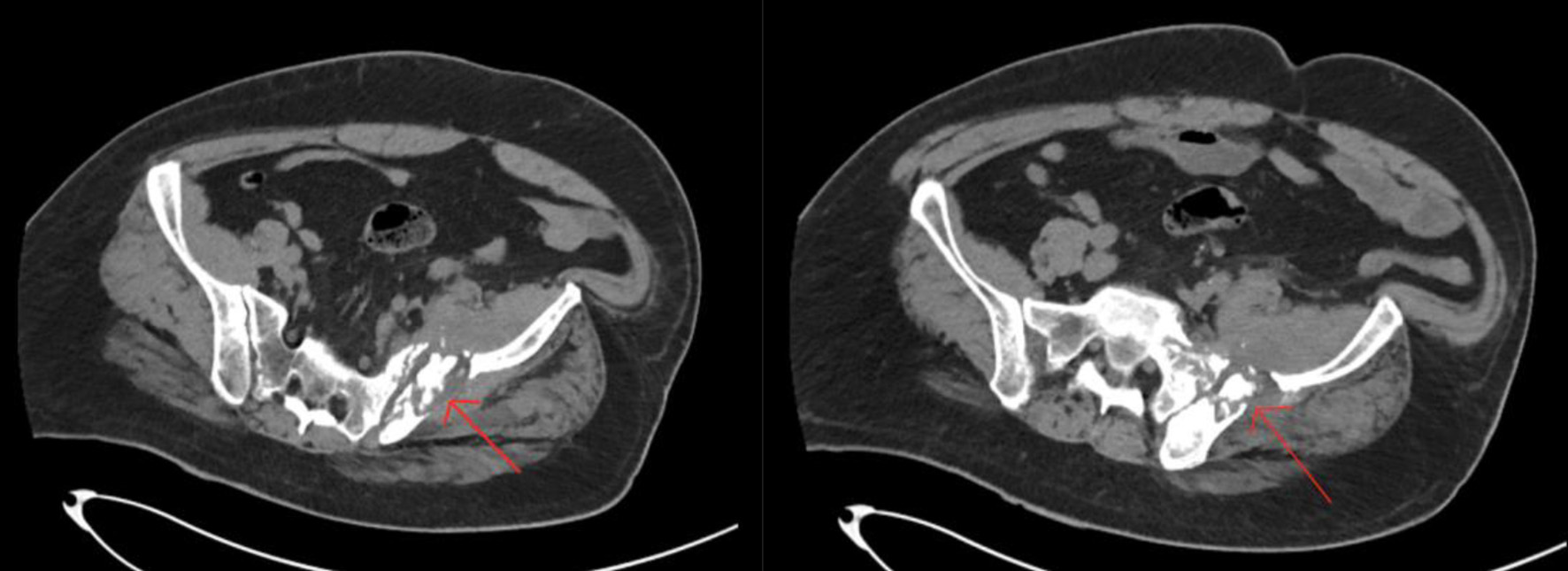

Upon admission, the patient was alert, oriented and his vitals were stable. His physical exam was only remarkable for pain upon ambulation. The digital rectal exam conveyed a smooth prostate without any nodules. The patient’s family history was significant for paternal prostate cancer. His labs were remarkable for hemoglobin of 10.6 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume of 79.4%, platelet count of 432 × 103/UL, blood urea nitrogen of 22 mg/dL, and alkaline phosphatase of 119 U/L. Throughout his stay at the hospital, his white blood cell count fluctuated with a minimum of 9.8 × 103/UL and a maximum of 12.5 × 103/UL. The lower extremity CT scan conveyed an aggressive permeative lytic destructive bone process of the left iliac bone adjacent to the sacroiliac joint and involvement of the sacrum which was concerning for nonspecific neoplastic process (Figs. 1 and 2).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Coronal computer tomography scan of the lower extremity identifying the lesion on the left hip (arrows). |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Axial computer tomography scan of the lower extremity identifying the lesion on the left hip (arrows). |

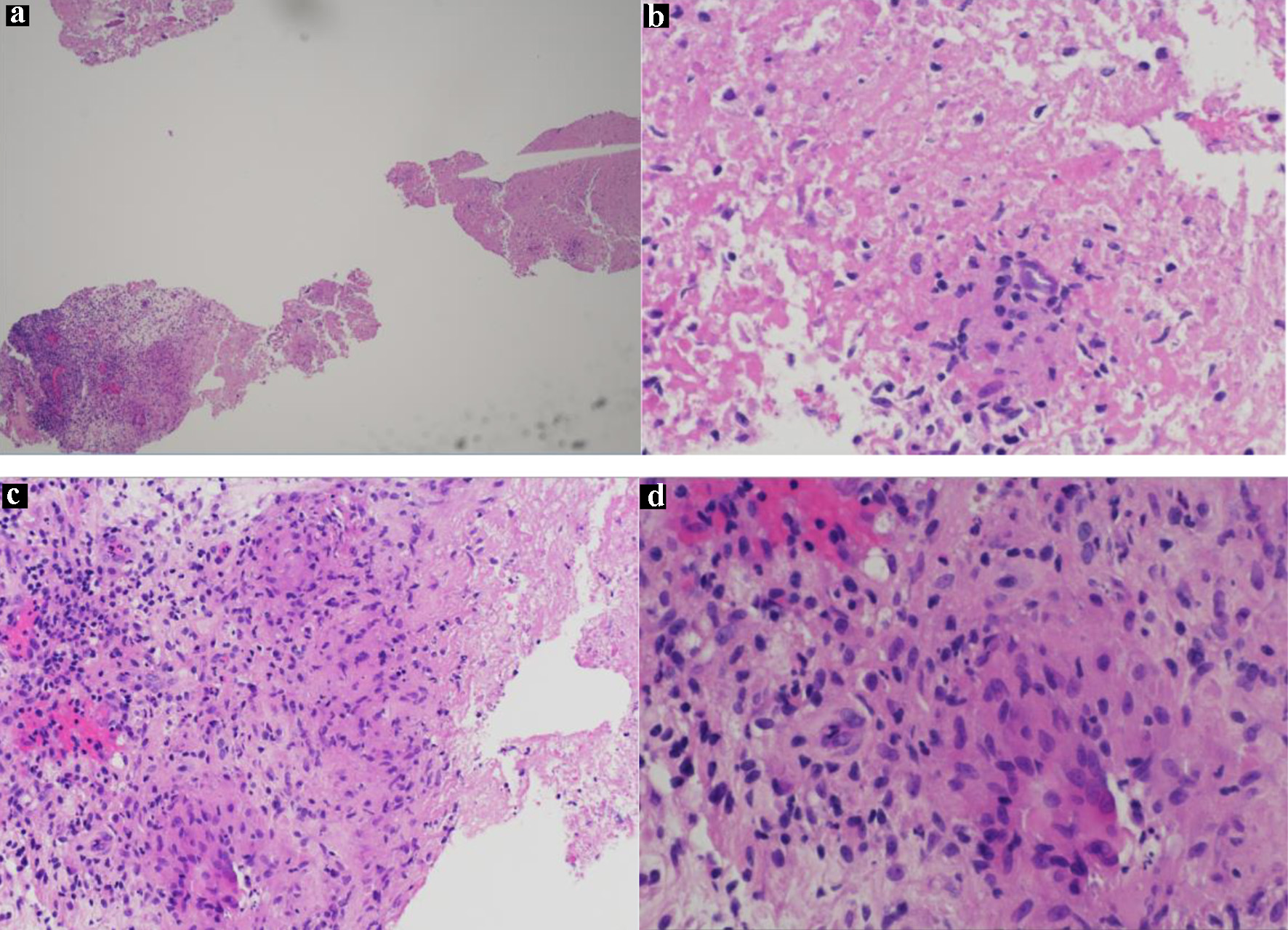

As per hematology and oncology specialist recommendation, a pan CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast was done. The CT of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast identified similar results as the CT scan of the lower extremity done upon admission. The CT of the chest with contrast was unremarkable. The pan CT confirmed that the lytic lesions were only localized to the hip whereas the CT of the prostate was normal but demonstrated prostate gland enlargement. Hematology and oncology specialist also recommended a hip bone biopsy, PSA panel, serum protein electrophoresis, and iron studies. The PSA was 5.66 ng/mL. The iron studies conveyed serum iron of 31 µg/dL and ferritin of 172 ng/mL. The serum protein electrophoresis showed total protein of 6.9 g/dL, albumin of 3.2 g/dL, serum alpha-1-globulin of 0.4 g/dL, alpha-2-globulin of 1.2 g/dL, beta-1-globulin of 0.4 g/dL, beta-2 globulin of 0.5 g/dL, and gamma-globulin of 1.1 g/dL. These results were consistent with acute inflammatory patterns. The iliac soft tissue biopsy identified fragments of predominantly necrotic tissue with a fragment of fibrocollagenous tissue with rare non-necrotizing granulomas (Fig. 3). The DNA probe of the bone biopsy identified Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex.

Click for large image | Figure 3. (a) H&E slide (low magnification, × 4) shows necrotic and viable tissue with non-necrotizing granuloma; (b) H&E slide (low magnification, × 10) shows granuloma and necrotic tissue; (c) H&E slide (low magnification, × 10) of well-formed granulomas showing the epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells; (d) H&E slide (high magnification, × 40) of a granuloma showing epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. H&E: hematoxylin and eosin. |

Treatment

The patient was started on rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol (RIPE), and vitamin B6 for 2 months and continued rifampin, isoniazid, and vitamin B6 for 7 months.

Follow-up and outcomes

On follow-up, the patient was ambulating without assistance. The patient claimed that the hip pain has significantly subsided after the initiation of the RIPE therapy.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

TB primarily affects the lungs; however, involvement of extrapulmonary areas, such as the lymph nodes, may occur [1]. OATB, also known as TB of the bone and joint or musculoskeletal TB, is an ancient disease that dates back to Egyptian mummies 9,000 years ago [1]. It is considered a rare form of TB, accounting for 1-5% of all TB cases. However, after pleural and lymph nodes, it is still the third most common type of extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB), making up of 18% of all EPTB cases [1, 4]. According to WHO, the incidence of all forms of TB, with 91 cases per 100,000, in the Dominican Republic has been estimated to be among the highest in the Americas [3]. However, it represents a major diagnostic challenge as the condition is often misdiagnosed, especially when it mimics other pathologies such as prostate cancer. The misdiagnosis is also attributed to the scarcity of the incidence and prevalence of OATB, a lack of information about the disease and statistical data in literature [5]. Most patients with OATB are not accurately diagnosed during the initial stages of the disease due to the vague, overlapping, and gradual onset of symptoms.

Due to hematogenous spread through the paravertebral plexuses, the most common site of OATB is the anterior inferior portion of the vertebral body (Pott’s disease), although 9.7% of OATB involves the sacroiliac joint [6-9]. In addition, although rare, literature has found that hematogenous bone metastases from the lungs also occur through Batson’s plexus [7]. This is because 13% of the blood from the bronchial arteries returns through the bronchial veins to reach the azygous and the accessory hemiazygos systems that drain to the Batson’s plexus [7]. The predisposition for other large joints and bones can also be explained by the rich vascular supply of the vertebrae and growth plates of the long bones [7, 10]. The pathophysiology of OATB can be described when a granuloma erodes the cartilaginous endplate of either a joint or a disc space and narrows it [10].

The vague symptoms of hip pain in this case, corresponding with the lesions seen in the left iliac bone adjacent to the sacroiliac joint may also direct the diagnosis toward a neoplastic differential. Persistent low back pain and difficulty with walking is present in all disease processes. TB sacroiliitis shows the same findings as OATB with destructive lesions, joint widening, and sclerosis of the margins. However, several studies have found that the iliac joint aspirates to be negative for TB. Histology reports of sacroiliac joint biopsy found acid-fast bacilli in only 60% of cases [10]. This may again be attributed to the paucibacillary nature of OATB. This lack of specific findings further necessitates the reason for further diagnostic testing to diagnose OATB.

In addition to the rarity of OATB, what makes this case most noteworthy is the overlap of symptoms concurrent with bone pathology from prostate cancer. The findings of this case made it difficult to differentiate TB from metastatic lesions without biopsy confirmation. First, a positive family history of prostate cancer doubles the risk of prostate cancer in this patient [11]. Secondly, the lack of lymphadenopathy in this patient further complicated the differential diagnosis which is a common finding in EPTB. In a study of 533 cases of prostate cancer it was found that palpable lymph nodes were actually only present in 30-40% of cases and lymphadenitis was observed in a mere 13.5% of cases [12]. OATB of the sacroiliac joint presents with palpable mass or cutaneous fistulae in approximately half of cases [8], but these were absent here. This further clouded the diagnosis of TB, whereas the presence of an abscess or fistula would have strongly suggested an infectious etiology and warrants surgical intervention alongside RIPE therapy [8]. Finally, the digital rectal exam has limited sensitivity and negative predictive value even in patients positive for prostate cancer symptoms, at 28.6% and 84.2% respectively [12]. The negative findings were not grounds to rule out malignancy. Thus, it becomes key that histopathology through a biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis of prostatic cancer or OATB [10, 12].

The urinalysis for this patient revealed sterile pyuria with a negative culture and chest X-rays [12]. The patient’s PSA was only mildly elevated - the observed value of 5.66 ng/mL in this patient is associated with a 22-27% overall risk of prostate cancer [13]. One study found a mean preoperative PSA level of 8.26 ng/mL in men undergoing radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer [14]. In patients with osseous metastatic disease, the PSA level is typically more significantly elevated. A retrospective analysis of 270 patients with prostate cancer found that of 153 patients with osseous metastasis confirmed by bone scintigraphy, 98% (150) had PSA levels > 20 ng/mL. In the remaining 117 patients without bony metastasis, 94% had PSA levels < 20 ng/mL [15]. While the patient’s values are not inconsistent with localized prostatic cancer, they would represent an atypically low value for metastatic disease advanced enough to cause the observed bony lesions. PSA appears to be a strong discriminatory tool in ruling out metastatic prostate cancer when confronted with nonspecific symptoms, as in this case.

In addition, as seen in this patient, clinical evidence suggests that TB does in fact begin as non-necrotizing and then develops into full caseous necrotizing granulomas through a hypersensitivity reaction, precipitated by CD4+ T cells once faced with a high antigenic load [16]. Other cases have also shown that OATB reveals bone and joint lesions to be paucibacillary [16]. Therefore, it is crucial to utilize advanced techniques early on for prompt diagnoses of patients with non-specific symptoms; particularly when the constellation of symptoms and initial blood work is inconsistent with more common etiologies. This can aid in formulating an appropriate treatment plan to avoid progression of OATB.

Learning point

Adequate diagnosis of complex presentations requires careful evaluation of multiple possible etiologies. A holistic view may be critical in treatment of such cases. A detailed patient history can expand the differential diagnosis list. In this case, the Dominican Republic has one of the highest numbers of tuberculosis cases in the Americas. Given that fact, OATB was a possibility. The atypical location of the lesions, the duration of the chronic pain, and family history of prostate cancer leaned more towards prostate cancer with metastases to the hip. A bone biopsy was required to rule out prostate cancer metastases and rule in Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Conclusion

In this case, the patient presented with chronic left hip pain. Given the family history of prostate cancer, and lesions on the left hip identified by the CT, the initial assessment leaned towards prostate cancer. However, the negative digital rectal examination (DRE) and mildly elevated PSA warranted a biopsy. The biopsy revealed necrotic fibrocollagenous tissue with rare non-necrotizing granulomas. Mycobacterium tuberculosis was confirmed with a DNA probe. Therefore, the patient was immediately started on the RIPE therapy with resolution of his ambulation issues.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Patient was consented and written consent is available upon request.

Author Contributions

Seyed Mohammad Nahidi, Harman Singh, and Sharang Tickoo performed the research including data collection and wrote the paper. Leonidha Duka and Jung Won reviewed the case report and provided expert clinical knowledge to revise critically. Jennifer Gulas was the Internal Medicine attending, reviewed the case report, and provided expert clinical knowledge to revise critically.

Data Availability

Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

| References | ▴Top |

- Pigrau-Serrallach C, Rodriguez-Pardo D. Bone and joint tuberculosis. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(Suppl 4):556-566.

doi pubmed - Yusuf M, Finucane L, Selfe J. Red flags for the early detection of spinal infection in back pain patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):606.

doi pubmed - Reinoso J, Arias J, Santana G. Case of Pott's disease in a 17-year-old patient in the Dominican Republic. Cureus. 2019;11(6):e4922.

doi pubmed - Plesea IE, Anusca DN, Procopie I, Huplea V, Niculescu M, Plesea RM, Ghelase SM, et al. The clinical-morphological profile of bone and joints tuberculosis - our experience in relation to literature data. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2017;58(3):887-907.

- Chen CH, Chen YM, Lee CW, Chang YJ, Cheng CY, Hung JK. Early diagnosis of spinal tuberculosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016;115(10):825-836.

doi pubmed - Mittal S, Khalid M, Sabir AB, Khalid S. Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging findings between pathologically proven cases of atypical tubercular spine and tumour metastasis: a retrospective study in 40 patients. Asian Spine J. 2016;10(4):734-743.

doi pubmed - Ramlakan RJ, Govender S. Sacroiliac joint tuberculosis. Int Orthop. 2007;31(1):121-124.

doi pubmed - Gao F, Kong XH, Tong XY, Xie DH, Li YG, Guo JJ, Tang TS. Tuberculous sacroiliitis: a study of the diagnosis, therapy and medium-term results of 15 cases. J Int Med Res. 2011;39(1):321-335.

doi pubmed - Papagelopoulos PJ, Papadopoulos E, Mavrogenis AF, Themistocleous GS, Korres DS, Soucacos PN. Tuberculous sacroiliitis. A case report and review of the literature. Eur Spine J. 2005;14(7):683-688.

doi pubmed - Mishra KG, Ahmad A, Singh G, Tiwari R. Tuberculosis of the prostate gland masquerading prostate cancer; five cases experience at IGIMS. Urol Ann. 2019;11(4):389-392.

doi pubmed - Ehlers S, Schaible UE. The granuloma in tuberculosis: dynamics of a host-pathogen collusion. Front Immunol. 2012;3:411.

doi pubmed - Jones D, Friend C, Dreher A, Allgar V, Macleod U. The diagnostic test accuracy of rectal examination for prostate cancer diagnosis in symptomatic patients: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):79.

doi pubmed - Gretzer M, Partin A. PSA levels and the probability of prostate cancer on biopsy. European Urology Supplements. 2002;1(6):21-27.

doi - Jeschke S, Beri A, Grull M, Ziegerhofer J, Prammer P, Leeb K, Sega W, et al. Laparoscopic radioisotope-guided sentinel lymph node dissection in staging of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2008;53(1):126-132.

doi pubmed - Kamaleshwaran KK, Mittal BR, Harisankar CN, Bhattacharya A, Singh SK, Mandal AK. Predictive value of serum prostate specific antigen in detecting bone metastasis in prostate cancer patients using bone scintigraphy. Indian J Nucl Med. 2012;27(2):81-84.

doi pubmed - Flais J, Coiffier G, Brillet E, Perdriger A, Guggenbuhl P. Atypical presentation of spine bone metastasis in prostate cancer mimicking Pott's disease. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2017;14(2):239-240.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.