| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 13, Number 6, June 2022, pages 263-268

Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy Secondary to Cryptococcal Meningoencephalitis in a Patient With Multiple Sclerosis

Shawna Stephensa, Benjamin Fogelsona, c, Rachel P. Goodwinb, Gayathri K. Baljepallyb, Raj Baljepallyb

aDepartment of Medicine, University of Tennessee Graduate School of Medicine, Knoxville, TN, USA

bDepartment of Cardiology, University of Tennessee Graduate School of Medicine, Knoxville, TN, USA

cCorresponding Author: Benjamin Fogelson, Department of Medicine, University of Tennessee Medical Center, Knoxville, TN 37920-6999, USA

Manuscript submitted December 12, 2021, accepted May 9, 2022, published online June 11, 2022

Short title: Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3884

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Takotsubo or stress-induced cardiomyopathy is described as reversible left ventricular dysfunction that develops following a stressful emotional or physical event primarily occurring in postmenopausal females. Many physiologic triggers have been identified in the pathogenesis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, including diseases which affect the central nervous system such as traumatic brain injuries, hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes, epilepsy, and central nervous system infections, including meningitis and encephalitis; however, there are very few published case reports of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the setting of fungal meningoencephalitis. We present a unique case of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy secondary to Cryptococcus neoformans meningoencephalitis in a middle-aged female with a history of multiple sclerosis who was taking immunosuppressive therapy.

Keywords: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy; Cryptococcus neoformans; Meningoencephalitis; Multiple sclerosis

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, also known as stress-induced cardiomyopathy or broken-heart syndrome, is characterized by transient systolic dysfunction and apical ballooning of the left ventricle [1]. The exact pathophysiology of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is unclear, but many experts agree that a stress-induced surge of catecholamines causes injury to the myocardium [1]. It is hypothesized that high circulating levels of epinephrine intensely activate B2 adrenoreceptors which cause an intracellular signaling class switch to occur from a stimulator/activator (Gs) to an inhibitor (Gi) leading to negative inotropic effects, and ultimately, the myocardial stunning observed in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy [1, 2]. Stress-induced cardiomyopathy commonly affects postmenopausal women following a stressful emotional or physical event likely secondary to the loss of circulating estrogen [1, 2]. Estrogen receptors, expressed throughout the cardiovascular and nervous systems, play an important role in modulating certain autonomic functions and can assist with prevention of cardiovascular disease [1]. Although it is not completely understood, it is likely that postmenopausal females are at increased risk for the development of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy due to the loss of circulating estrogen and its cardioprotective effects.

The initial presentation of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy can mimic that of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), with chest pain being the most common symptom [2]. In patients with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, electrocardiogram will often reveal T-wave inversions in the precordial leads and occasionally ST-elevations without associated reciprocal depressions. Cardiac enzymes (troponin and creatinine kinase) will often be elevated in patients with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, but typically to a lesser extent than patients with ACS [1, 2]. In comparison to isolated wall-motion abnormalities in ACS, the common echocardiogram findings in patients with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy are wall motion abnormalities that involve multiple coronary artery distributions. While echocardiogram has proven very useful in the diagnosis of “clinical” Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the critical care setting, the gold standard for diagnosis is coronary angiography, which demonstrates nonobstructive coronary artery disease [1, 2].

Severe infection and sepsis are well-known triggers of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy [3]. Recent studies have also linked the brain-heart axis, a concept referred to as neurocardiology, to the development of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy [4, 5]. Specifically, areas of the nervous system, including the hypothalamus and areas of the medulla, play a role in modulating cardiac function, particularly in times of stressful events or homeostatic reflexes [4]. Furthermore, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is one of the most common cardiac abnormalities induced by central nervous system (CNS) disorders. Many CNS disease processes including stroke (both hemorrhagic and ischemic), seizure, and traumatic brain injury are known causes of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy [6]. Additionally, CNS infections including meningitis and encephalitis, primarily bacterial, have been identified as causes of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy [6, 7]. However, few case reports have described Takotsubo cardiomyopathy secondary to fungal CNS infections. We report a unique case of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy secondary to severe case of Cryptococcus neoformans meningoencephalitis in an immunocompromised patient with multiple sclerosis.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 60-year-old woman with a prior history of epilepsy presented to the emergency department after experiencing seizure-like activity. She initially presented to the emergency department approximately 5 days prior to admission when she first experienced an unwitnessed fall. At that time, she was found to have a 3-cm laceration on the medial aspect of her forehead which was repaired. A computed tomography (CT) of the head without contrast performed at that time was unremarkable, and the patient was discharged home from the emergency department in stable condition. Over the next 4 days, the patient began to develop nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, generalized weakness, and severe fatigue. She reportedly experienced seizure-like activities which were described as altered mental status and diffuse shaking movements. Patient had also complained of recent non-specific headaches, low back and neck pain, as well as hearing loss that began approximately 7 days prior to admission. The family also reported that over the last few days, the patient had developed hallucinations which manifested as talking to her daughter who had been deceased for over 3 years.

In addition to epilepsy, she has a past medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, depression, anxiety, migraines, and multiple sclerosis. Of note, she had no reported cardiovascular history. Prior to her admission, she had undergone a yearly medical examination with her primary care physician which revealed a normal electrocardiogram (ECG) and recent CT scan of the chest demonstrated no significant coronary calcifications. Her home medications include levetiracetam 500 mg twice daily, atorvastatin 40 mg daily, carvedilol 12.5 mg daily, gabapentin 300 mg twice daily, lisinopril 40 mg daily, and venlafaxine 75 mg daily. Additionally, she was on immunosuppressive therapy with fingolimod 0.5 mg daily for her multiple sclerosis.

On initial presentation, she had a temperature of 37.6 °C (99.7 °F), heart rate of 110 beats per minute (bpm), blood pressure of 191/84 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute and an oxygen saturation of 97% on room air. Admission physical examination was notable for bilateral periorbital ecchymosis, a small forehead laceration with sutures in place with surrounding ecchymosis and bruising. Cardiopulmonary auscultation revealed tachycardia with a regular rhythm, no murmurs, rubs, or gallops appreciated, and her lungs were clear to auscultation throughout all lung fields without wheezing, rales, or rhonchi. Her speech was fluent without aphasia. Cranial nerves II-XII were intact bilaterally, and she had 5/5 muscle strength with intact sensation throughout the upper and lower extremities bilaterally. Her reflexes were normal and Babinski sign was negative bilaterally. No dysmetria on finger to nose or heel to shin was noted. Additionally, there was no evidence of nuchal rigidity, with negative Kernig and Brudzinski maneuvers.

Diagnosis

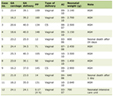

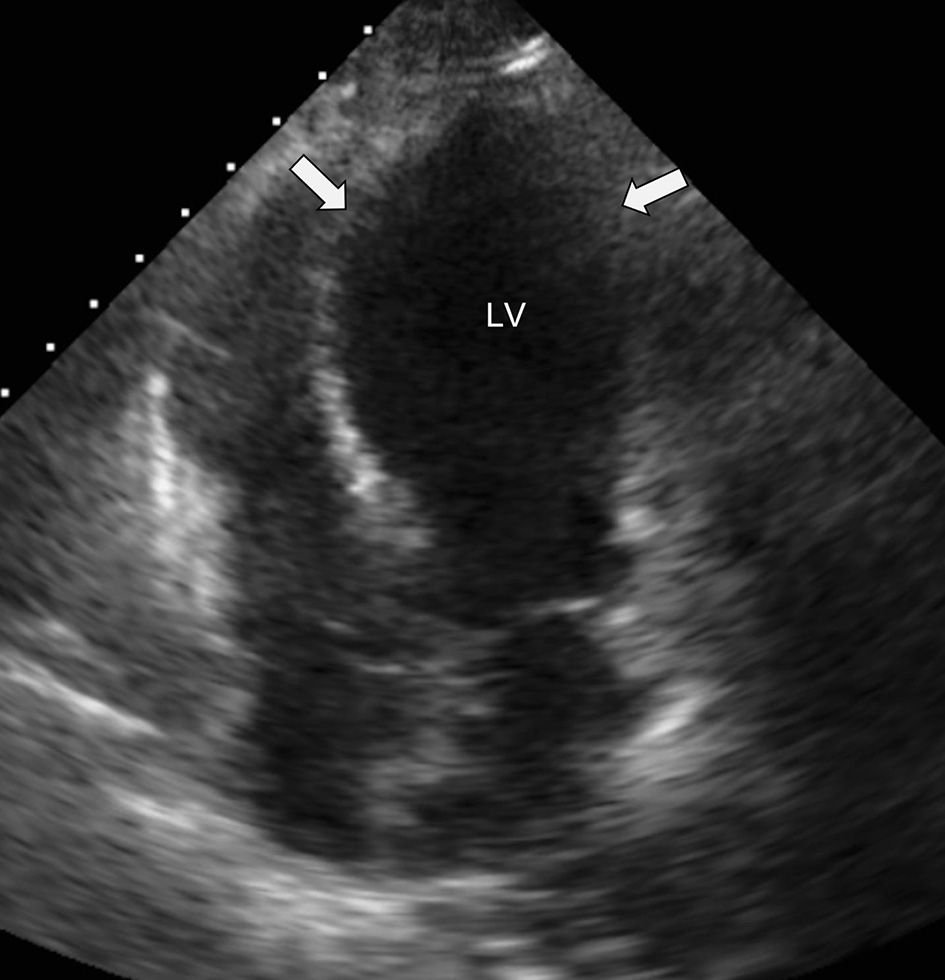

The patient’s initial lab work, including complete blood count (CBC), basic metabolic panel (BMP), and lactic acid are outlined in Table 1. Cardiac high-sensitivity troponin T was 0.03 ng/mL (reference range: 0.00 - 0.78 nm/mL) and an ECG revealed sinus tachycardia with a rate of 112 bpm and diffuse non-specific ST-segment depression (Fig. 1). CT scan of the head without contrast was performed and revealed a small frontal scalp hematoma but was negative for acute intracranial findings. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of brain and brainstem revealed progressive periventricular white matter lesions consistent with multiple sclerosis. Blood cultures were also obtained on admission.

Click to view | Table 1. Patient’s Lab Work on Admission |

Click for large image | Figure 1. Electrocardiogram on presentation to the emergency department with seizure-like activity, headache, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and severe fatigue. |

On day 1 of her hospitalization, patient continued to complain of back pain, nausea, vomiting and new onset photosensitivity. Given concerns for possible breakthrough seizures, an electroencephalogram (EEG) was performed, which demonstrated diffuse slowing of the background indicative of an encephalopathy. On day 2 of her hospitalization, the patient’s condition had worsened. She was found to be obtunded and was unable to follow any commands. Repeat images of the head and neck were obtained and were noted to be unremarkable. Her blood cultures obtained on admission were found to have a heavy growth of yeast.

Treatment

Given her altered mental status in the setting of immunosuppressive therapy as well as fungal positive blood cultures, there was concern for cryptococcal meningitis. Lumbar puncture was performed, and she was started on amphotericin. Cerebrospinal fluid studies revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 0 (reference range: 0 - 5), red blood cell (RBC) count of 2,434 cells (reference range 0), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) total protein of 58 mg/dL (reference range: 8 - 32 mg/dL), and CSF glucose of 3 mg/dL (reference range: 40 - 70 mg/dL), and CSF Cryptococcus antigen was found to be positive. The patient’s blood and CSF cultures confirmed the growth of Cryptococcus neoformans and flucytosine was added to her treatment regimen.

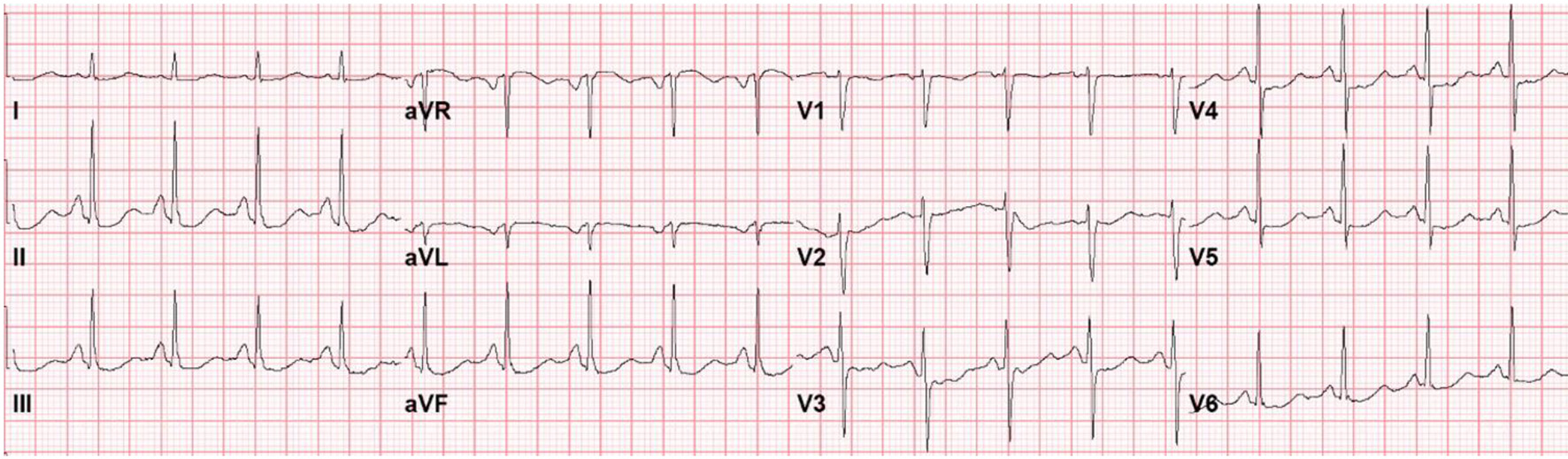

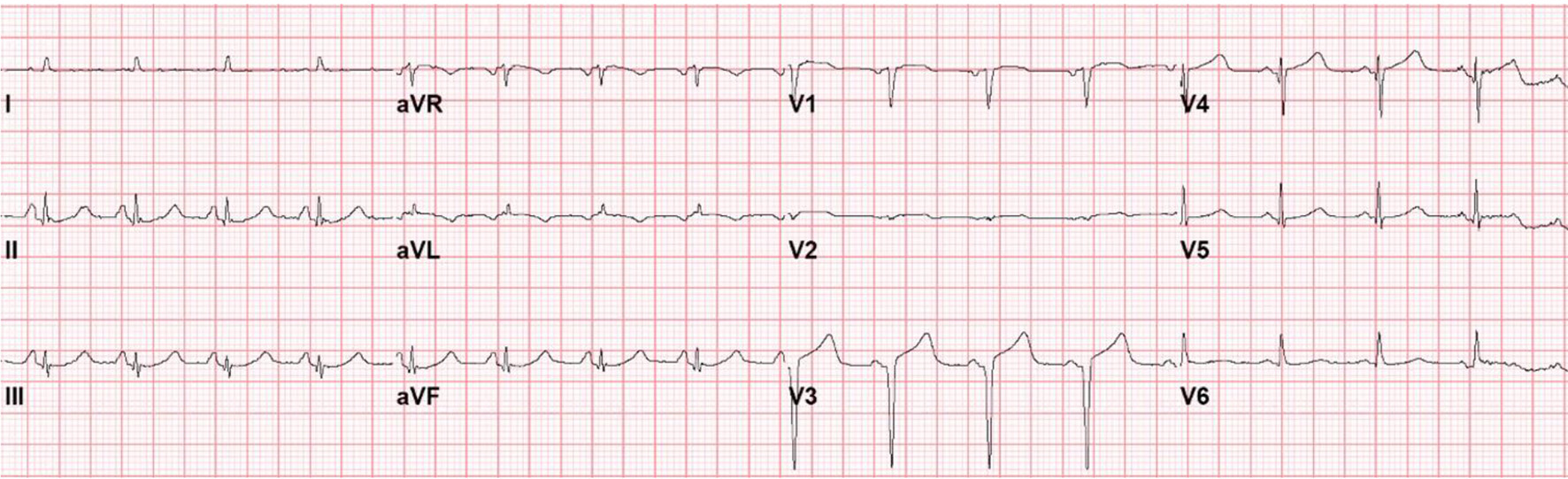

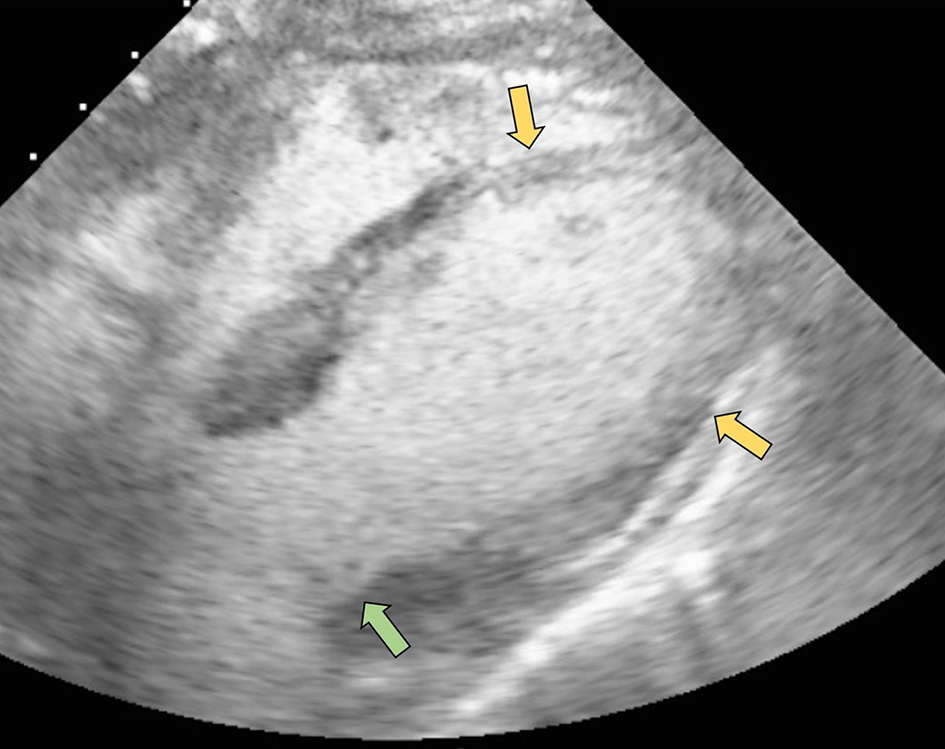

On hospital day 4, the patient suddenly became unresponsive and hypoxic requiring endotracheal intubation. She then became bradycardic, with progression to cardiac arrest. Advance cardiac life support was initiated and return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) was achieved after five rounds of resuscitative efforts. Cardiac studies obtained at this time revealed an elevated troponin of 1.43 ng/mL (reference range: 0.00 - 0.78 ng/mL); however, repeat ECG revealed Q waves anteriorly, poor R wave progression and ST-segment elevations in leads V1 to V4 without reciprocal ST depressions in the inferior leads (Fig. 2). An echocardiogram was then obtained which demonstrated an ejection fraction of 20-25% with hypokinesis of the anterior, anteroseptal, and apical segments as well as basal hyperkinesis, consistent with classical Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (Figs. 3, 4). However, coronary angiography to rule out ACS had to be deferred due to the severe hemodynamic instability requiring dual vasopressor support with norepinephrine and epinephrine. Of note, the patient underwent CT angiogram of the chest, which again demonstrated no significant coronary calcifications.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Electrocardiogram following cardiopulmonary arrest and resusitation. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Apical five-chamber view with apical ballooning of the LV (white arrows) seen with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. LV: left ventricle. |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Subcostal view with contrast ultrasound enhancing agent demonstrating hypokinesis of the anterolateral, anteroseptal, and apical segments (yellow arrows) as well as basal segment hyperkinesis (green arrow). |

Follow-up and outcomes

Unfortunately, she continued to clinically decline, requiring increasing amounts of norepinephrine, epinephrine, and vasopressin for hemodynamic support, and remained on significant ventilator support. Neurologic exam was performed after appropriately weaning her sedation which demonstrated no cough, corneal or pharyngeal reflexes. The decision was ultimately made by her family to transition to comfort care and the patient passed away shortly after.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is classically recognized as a cardiomyopathy that develops in older women following a stressful and emotional event due to a surge of circulating catecholamines. In addition to severe emotional stress, many pathophysiologic triggers causing Takotsubo cardiomyopathy have also been identified. Of the many known triggers, infections and CNS diseases have been found to be the most common [4-6]. A recent study demonstrated that sepsis and subarachnoid hemorrhage were the most common primary diseases associated with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the intensive care unit [3]. Muratsu et al highlighted that in the intensive care setting, many patients are unable to undergo coronary angiography to rule out coronary pathology due to hemodynamic instability [3]. Therefore, patients with echocardiographic findings of classic Takotsubo pattern, with cardiac wall abnormalities present in multiple coronary artery distributions as well as apical hypokinesis with basilar hyperkinesis, were documented as having “clinical” Takotsubo cardiomyopathy [3]. Similarly in our patient, due to her severe clinical state and hemodynamic instability, the diagnosis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy was made based on multiple clinical and historical factors. First, although our patient had risk factors for coronary disease, she had recent outpatient normal ECG and recent CT scan of the chest demonstrated no coronary calcifications. Second, the patient’s echocardiogram demonstrated hypokinesis in multiple coronary distributions, involving the entire apical segments, with hyperkinesis on the basal segments, classic for stress-induced cardiomyopathy. Lastly, her ECG changes associated with mild elevation in cardiac enzymes did not support that an acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction was the result of her new onset cardiomyopathy.

In addition to intracranial hemorrhage, many other neurologic diseases have also been linked to the development of stress-induced cardiomyopathy including seizures and CNS infections [4, 6-8]. During an acute neurologic event, activation of the medullary autonomic center leads to a massive release of both norepinephrine and epinephrine. The effect of norepinephrine on the basal segments of the myocardium via direct cardiac sympathetic nerve fiber simulation is hypothesized to play a greater role than adrenally released epinephrine in the pathophysiology if neurogenic Takotsubo cardiomyopathy [9]. The positive inotropic effect of direct sympathetic stimulation by norepinephrine leads to the significant basal hyperkinesis observed on echocardiography [9]. However, the pathophysiology of neurogenic Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is controversial.

Seizures have been a well-documented cause of stress-induced cardiomyopathy. According to Stollberger et al, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy secondary to seizures commonly affects younger males rather than the typical postmenopausal Takotsubo cardiomyopathy patient [8]. While our patient did have a history of epilepsy and presented with seizure-like activity, neurologic workup concluded that her presentation was due to encephalopathy in the setting of meningoencephalitis. CNS infections such as meningitis and encephalitis have been linked to the development of stress-induced cardiomyopathy. Kusaba et al reported a case of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy secondary to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus meningitis in a hemodialysis patient [7]. Most published case reports of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy secondary to infection have been found to be bacterial in origin, rather than fungal. Kherallah et al presented a rare case of cryptococcal meningitis-induced Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in a young human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patient who was noncompliant with antiretroviral therapy [10]. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first case of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy secondary to Cryptococcus neoformans meningoencephalitis in a patient without HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndromes (AIDs).

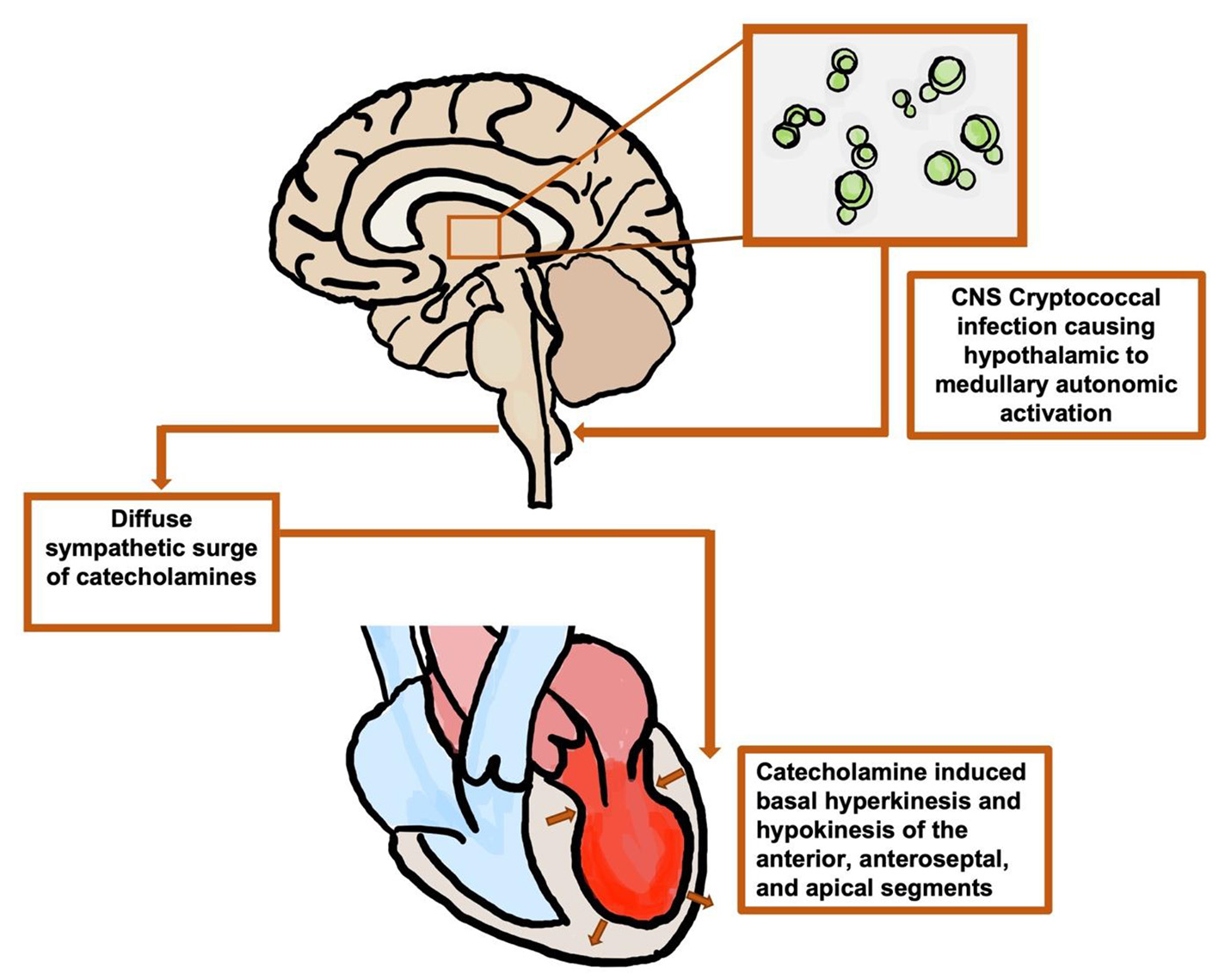

The fungus, Cryptococcus neoformans, is a common cause of meningitis worldwide that primarily affects the HIV/AIDS population [11]. Cryptococcus meningitis is the most common form of meningitis in areas with a high prevalence of HIV and accounts 10-20% of HIV-related deaths, in total more than 100,000 deaths per year [11]. Cryptococcus is contracted through the inhalation of spores from the environment that colonize the lung, and from there, the pathogen can disseminate [12]. In an immunocompetent person, the fungus will either be cleared by the immune system or result in an asymptomatic infection where the fungus will remain latent. If the host later becomes immunocompromised, they may present with symptomatic reactivation of the latent infection. In comparison, in immunocompromised patients, Cryptococcal neoformans commonly results in a symptomatic active infection, causing inflammation of the lungs and pulmonary nodules, and possibly disseminates to infect any organ system. In general, Cryptococcus neoformans tends to have a predilection to disseminate to the CNS causing meningoencephalitis [12]. World-wide there are estimated to be one million cases of cryptococcal meningitis annually and a 3-month mortality rate of > 60% [11]. As stated previously, Cryptococcus neoformans can directly affect any organ system including the cardiovascular system given its ability to rapidly disseminate [12]. However, few studies have presented the indirect cardiovascular effects of cryptococcal CNS infections by way of the brain-heart axis. It is hypothesized that the brain-heart axis is initially activated by excitation of the hypothalamus in the limbic system followed by excitation of the medullary autonomic center. This ultimately leads to a diffuse sympathetic surge of catecholamines inducing basal hyperkinesis and hypokinesis of the anterior, anteroseptal, and apical segments of the myocardium [1] (Fig. 5). Suzuki et al demonstrated brain activation in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy patients by measuring cerebral blood flow in both the acute and chronic phases of the disease. In this study, cerebral blood flow was measured with 99mTc ethyl cysteinate dimer (99mTc-ECD) brain single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). During the acute phase, left ventriculogram revealed the classic finding of apical ballooning, and SPECT revealed an increase in cerebral blood flow to the hippocampus, brainstem, and basal ganglia with a decrease in cerebral blood flow noted to the prefrontal cortex. During the chronic phase, cardiac wall motion abnormalities subsided; however, brain activation remained to some extent suggesting that recovery in cardiac function precedes brain activation [5].

Click for large image | Figure 5. Illustration of the hypothesized brain-heart axis: cryptococcal meningoencephalitis leading to autonomic activation and a diffuse surge of catecholamines, negatively affecting the left ventricle. CNS: central nervous system. |

We present a unique case of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy secondary to cryptococcal meningoencephalitis in a middle-aged female with a history of multiple sclerosis receiving immunosuppressive therapy. Although our patient had significant historical, clinical, and echocardiographic data to support the diagnosis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, the main limitation of this report is the lack of coronary catheterization to definitively rule out ACS. However, this case has multiple learning points that should be stressed. Many critically ill patients, such as those admitted to intensive care unit, with suspected stress-induced cardiomyopathy are too unstable to undergo coronary angiography. Therefore, a detailed clinical history in combination with ECG, cardiac biomarkers, and echocardiogram findings should be utilized to support the diagnosis of stress-induced cardiomyopathy over ACS. Additionally, with the emergence of HIV/AIDS, there has been an increase in cryptococcal meningoencephalitis cases. Although the HIV/AIDS population is most commonly affected by cryptococcal infections, all immunocompromised individuals are at risk. Patients with multiple sclerosis are not commonly recognized as immunocompromised or at significant risk for opportunistic infections. However, many multiple sclerosis patients are on medications, such as fingolimod, that are immunosuppressive. Therefore, all patients with multiple sclerosis presenting with suspected infections should have a thorough medication review to identify those that are immunosuppressed and at risk for opportunistic infections.

Learning points

This case highlights the high morbidity and mortality of cryptococcal meningoencephalitis and the importance of prompt diagnosis to improve chances of survival. Our case also stresses the importance of understanding the impact of the brain-heart axis and identifying its rare, but severe, effects on the cardiovascular system including Takotsubo, or stress-induced, cardiomyopathy. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy should remain a differential diagnosis in middle-aged to elderly females presenting with cardiac symptoms, especially in the setting of a stressful event [1, 2]. Furthermore, although coronary angiogram is needed to rule out ACS, many clinical factors can be used to support the diagnosis of stress-induced cardiomyopathy, especially in the critically ill. Lastly, our case demonstrates that all immunocompromised individuals, including the HIV/AIDS population as well as patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy, are at risk for developing disseminated cryptococcal infections.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained.

Author Contributions

All authors reviewed the literature and helped write the manuscript. Benjamin Fogelson, Shawna Stephens, Rachel P. Goodwin, Gayathri K. Baljepally, and Raj Baljepally performed critical revisions of the article and approved the final version of manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

CNS: central nervous system; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; AIDS: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; ACS: acute coronary syndrome; ROSC: return of spontaneous circulation

| References | ▴Top |

- Akashi YJ, Goldstein DS, Barbaro G, Ueyama T. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a new form of acute, reversible heart failure. Circulation. 2008;118(25):2754-2762.

doi pubmed - Hurst RT, Prasad A, Askew JW, 3rd, Sengupta PP, Tajik AJ. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a unique cardiomyopathy with variable ventricular morphology. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3(6):641-649.

doi pubmed - Muratsu A, Muroya T, Kuwagata Y. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the intensive care unit. Acute Med Surg. 2019;6(2):152-157.

doi pubmed - Samuels MA. The brain-heart connection. Circulation. 2007;116(1):77-84.

doi pubmed - Suzuki H, Matsumoto Y, Kaneta T, Sugimura K, Takahashi J, Fukumoto Y, Takahashi S, et al. Evidence for brain activation in patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2014;78(1):256-258.

doi pubmed - Finsterer J, Wahbi K. CNS disease triggering Takotsubo stress cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177(2):322-329.

doi pubmed - Kusaba T, Sasaki H, Sakurada T, Kuboshima S, Miura H, Okabayashi J, Murao M, et al. [Takotsubo cardiomyopathy thought to be induced by MRSA meningitis and cervical epidural abscess in a maintenance-hemodialysis patient: case report]. Nihon Jinzo Gakkai Shi. 2004;46(4):371-376.

- Stollberger C, Wegner C, Finsterer J. Seizure-associated Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Epilepsia. 2011;52(11):e160-167.

doi pubmed - Wagner S, Guthe T, Bhogal P, Cimpoca A, Ganslandt O, Bazner H, Henkes H. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage as a trigger for Takotsubo syndrome: a comprehensive review. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2021;22(4):1241-1251.

doi pubmed - Kherallah RY, Algahmi W, Ibrahim MS, Suchdev K. Cryptococcal meningitis complicated by takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a case report. Austin J Clin Neurol. 2017;4(7):1130.

- Molloy SF, Kanyama C, Heyderman RS, Loyse A, Kouanfack C, Chanda D, Mfinanga S, et al. Antifungal combinations for treatment of cryptococcal meningitis in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(11):1004-1017.

doi pubmed - Sabiiti W, May RC. Mechanisms of infection by the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Future Microbiol. 2012;7(11):1297-1313.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.