| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 13, Number 7, July 2022, pages 335-340

Small Bowel Obstruction and Appendicitis in Patient With Fitz-Hughes-Curtis Syndrome

Marina K. Cugliaria, Trupti Panditb, Ramesh Panditc, d

aRowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine, Stratford, NJ, USA

bPediatrics Department, Inspira Medical Center, Vineland, NJ, USA

cDepartment of Medicine, Crozer Chester Medical Center, Upland, PA, USA

dCorresponding Author: Ramesh Pandit, Department of Medicine, Crozer Chester Medical Center, Upland, PA 19013, USA

Manuscript submitted April 12, 2022, accepted June 13, 2022, published online July 20, 2022

Short title: Fitz-Hughes-Curtis Syndrome

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3947

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Fitz-Hughs-Curtis syndrome is a manifestation of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) which begins with sexually transmitted organisms such as Chlamydia trachomatis (C. trachomatis) and, less commonly Neisseria gonorrhoeae. The infection is hypothesized to disseminate into the peritoneum via lymphatic, hematogenous, or ascending spread of the organisms. Progression of the disease can result in liver capsule inflammation (perihepatitis) and adhesion formation between organs. This case presentation illustrates a female who presented with symptomology consistent with small bowel obstruction (SBO) and acute appendicitis. The patient was incidentally found to have Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome during laparoscopic surgery, as noted by adhesions on peritoneal organs. These findings prompted a sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening which confirmed a C. trachomatis infection, completing the clinical picture for Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome. This case report highlights the need for an increased index of suspicion for Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome in a young female who presents with right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain in order to prevent future complications of PID, including infertility.

Keywords: Long-term complication; Adolescent medicine; Pelvic inflammatory disease; Fitz-Hughes-Curtis syndrome; Atypical appendicitis; Sexually transmitted disease; STI; Small bowel obstruction

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome is a manifestation of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) associated with Chlamydia trachomatis infections and less frequently with Neisseria gonorrhoeae [1]. In the USA, over 750,000 cases of PID are reported yearly, affecting young sexually active women of childbearing age [2]. Due to the unique disease presentation, the overall incidence of Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome is challenging to quantify. However, in adolescents, the rate is estimated to be approximately 4% [3].

The pathogenesis of Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome is hypothesized to be the dissemination of infection via the lymphatic, hematogenous, or direct ascending spread of organisms. Progression of the disease can result in liver capsule inflammation (perihepatitis) or adhesion formation between organs [2]. The adhesions can lead to right upper quadrant (RUQ) and right lower quadrant (RLQ) pain. Adhesions in the RUQ can mimic gallbladder pathologies such as cholelithiasis and cholecystitis. In contrast, pain in the RLQ may illustrate a clinical picture consistent with a small bowel obstruction (SBO) [4].

An additional rare complication of the peritoneal adhesions is SBO. SBO is a disruption in the flow of intraluminal contents and is a surgical emergency due to the risk of bowel ischemia. The most common etiology of SBO is postoperative adhesions. However, intra-abdominal adhesions resulting from inflammation may contribute to the pathology [5].

Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome is often diagnosed using computed tomography (CT) imaging and ultrasonography. Findings on a CT report concerning Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome coincide with increased hepatic capsular enhancement in the arterial phase [6]. However, it can often be an incidental finding during laparoscopic procedures.

While there are few studies and case reports documenting Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome in the adolescent population [4-6], none of these document its association with complications of appendicitis and bowel obstructions together. We present a case report illustrating a young female who presented with an SBO and appendicitis clinical picture that was incidentally found to have Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome during her laparoscopic surgery.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 15-year-old adolescent female with a past medical history of scoliosis presented to the emergency department with nausea and vomiting for 3 days and diffuse abdominal pain for 2 days. The patient described her vomiting included digestive food particles. Later, it transitioned to a yellow-colored liquid. On presentation, the emesis color was noted to be lime green. The patient denied fever, chills, diarrhea, constipation, vaginal irritation, change in normal vaginal discharge, malodor, dysuria, hematuria, polyuria, or polyphagia. The patient denied being sexually active, and the patient had no history of prior intra-abdominal surgeries. The patient endorsed a decrease in urine volume, considered to be secondary to dehydration from the upper gastrointestinal losses.

The patient’s vitals were remarkable for mild tachycardia (102 beats/min) and tachypnea (24 breaths/min). The patient’s abdominal exam was notable for diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation in all four quadrants as well as right-sided costovertebral angle tenderness. Bowel sounds were auscultated in all four quadrants. Cardiac and respiratory exams were unremarkable.

Diagnosis

The patient’s lab findings were notable for leukocytosis, elevated platelets, neutrophilia (80%), and hyponatremia. Liver enzymes were not elevated. Pregnancy and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) screening were both negative. A urinalysis was notable for nitrites, bacteria (2+), moderate ketones, few red blood cells, and few white blood cells.

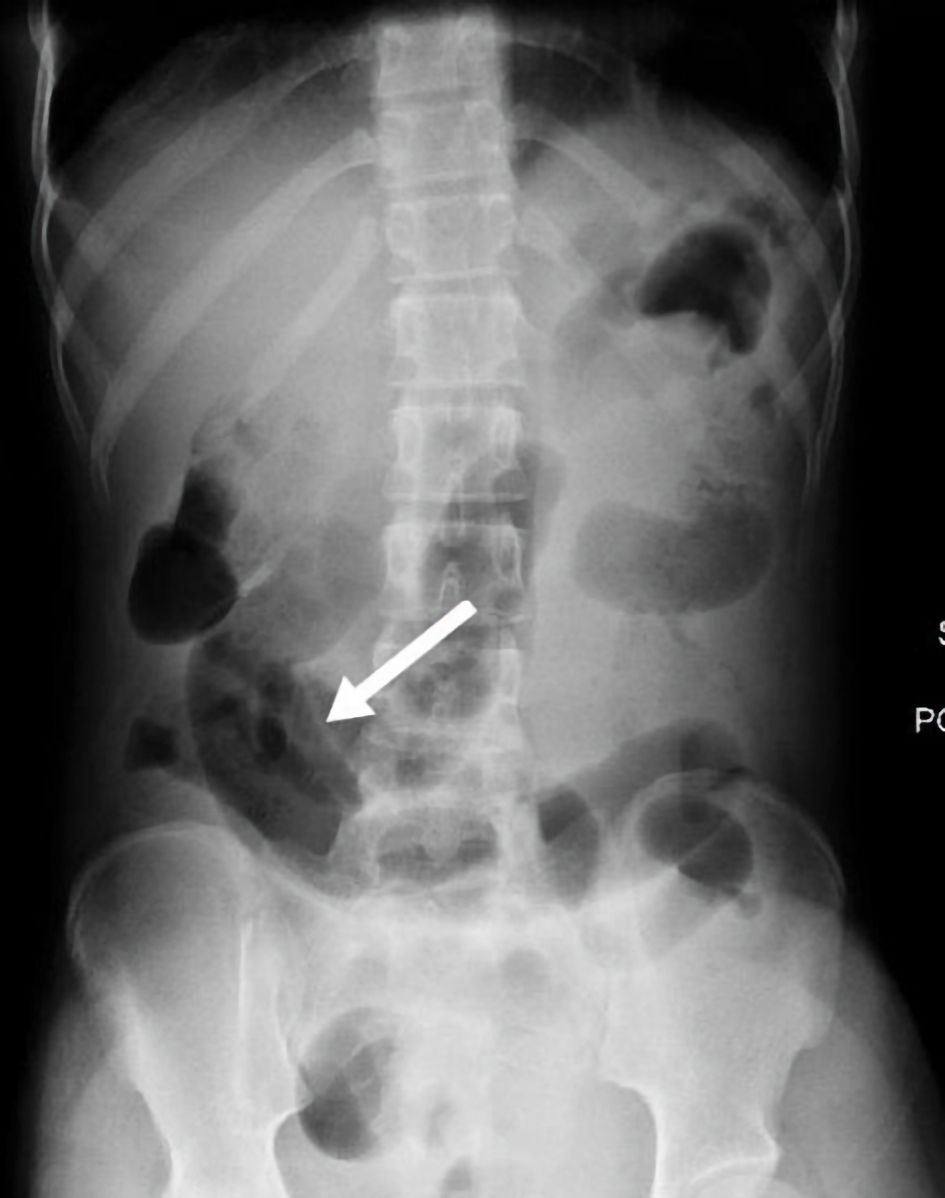

The patient was admitted for suspected acute pyelonephritis and was started on empirical antibiotics. She received ceftriaxone intravenously. Later, the patient experienced worsening abdominal pain and bilious emesis, which prompted an abdominal X-ray, which demonstrated dilated bowel loops in the RLQ and periumbilical area, as shown in Figure 1.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Abdominal X-ray showed moderately distended gas filled loops (white arrow). |

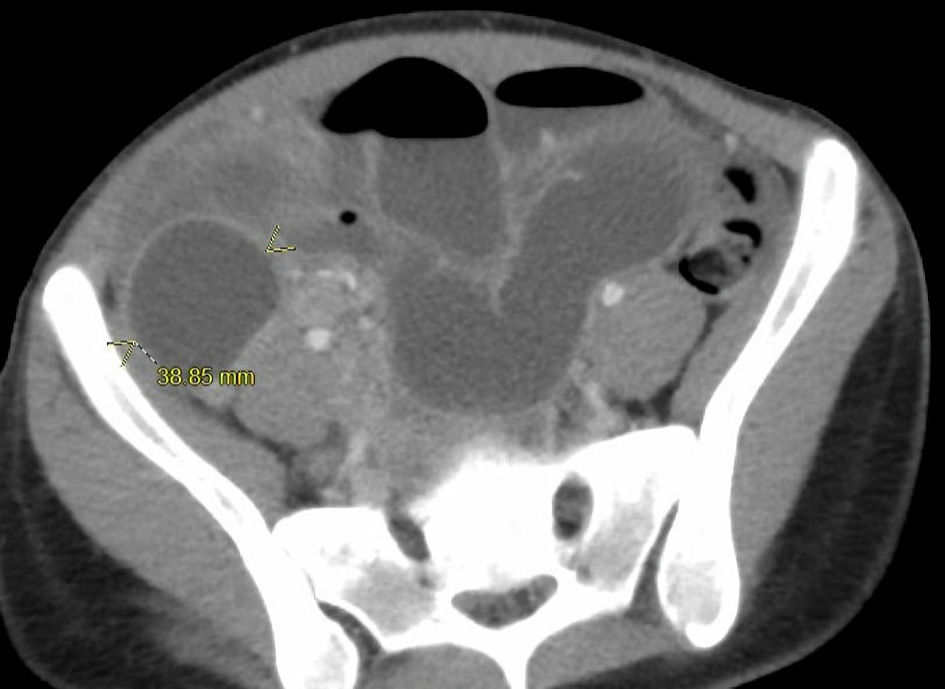

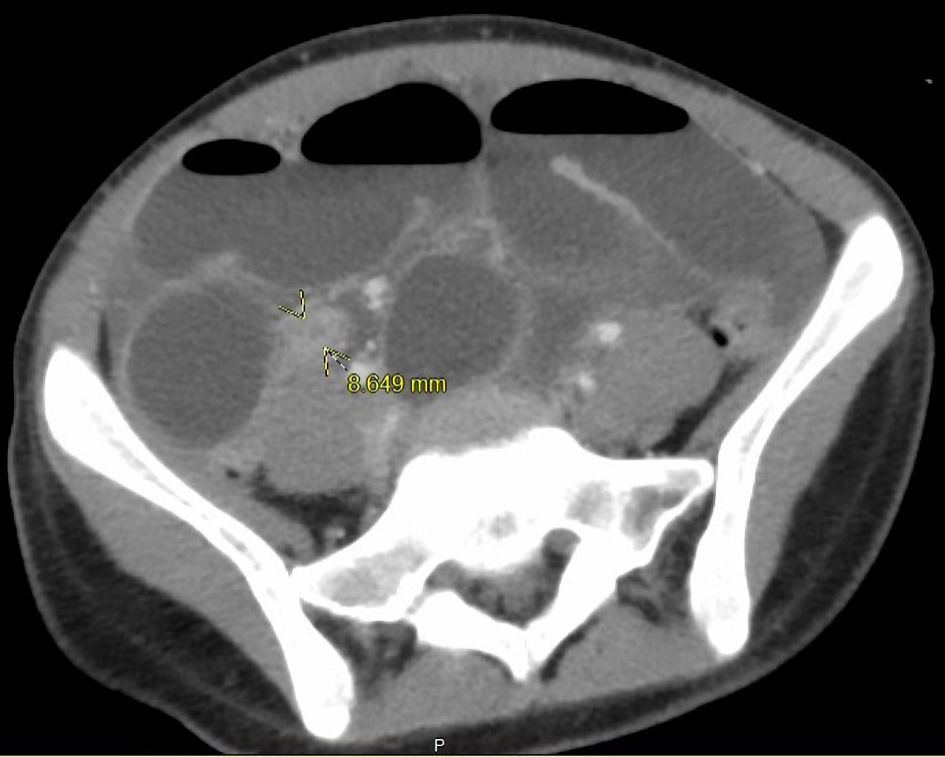

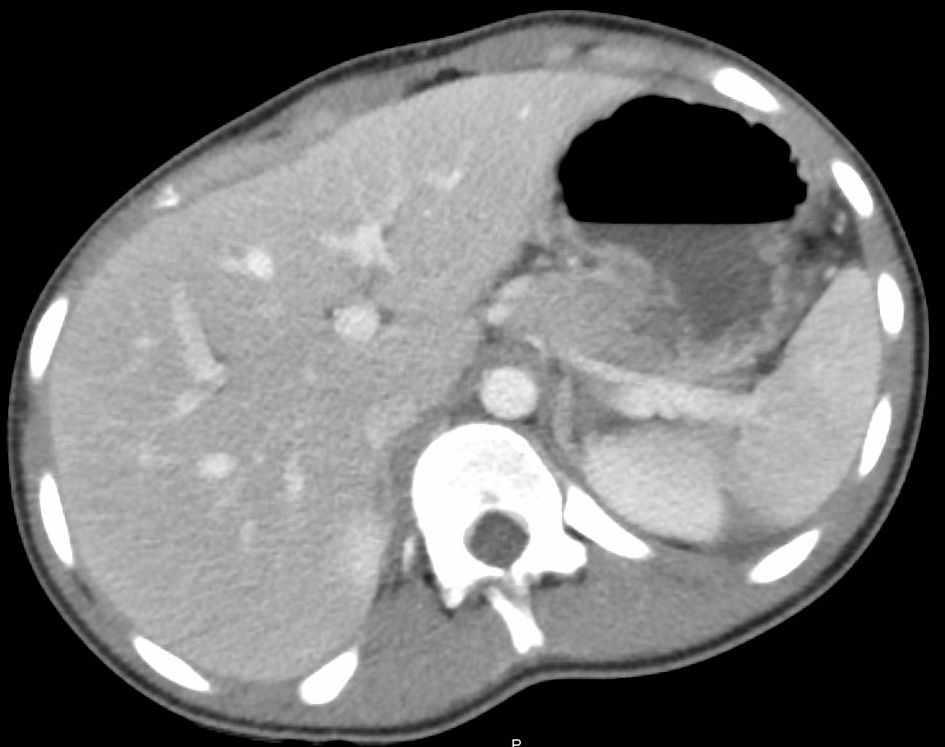

A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast demonstrated high-grade SBO with multiple fluid air levels and a 9 mm thick walled hyperenhancing structure arising from the cecum, with small complex free fluid in pelvis concerning for perforated appendicitis (Figs. 2, 3). The liver/biliary tract findings on the CT imaging were noted to be within normal ranges (Fig. 4). General surgery was consulted, and a nasogastric tube was placed for gastrointestinal decompression with a follow-up abdominal X-ray that showed resolving gas burden (Fig. 5). Metronidazole was added to the patient’s antibiotic regimen for broader coverage.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Axial CT image of abdomen and pelvis showed dilated bowels and air-fluid levels (arrows). CT: computed tomography. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Axial CT image of abdomen and pelvis showed an inflamed appendix (arrows). CT: computed tomography. |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Axial CT image of abdomen and pelvis showed no liver capsular enhancement or hepatomegaly. CT: computed tomography. |

Click for large image | Figure 5. Abdominal X-ray on the next day showed resolving distention of small bowel loops (white arrow). |

Treatment

A laparoscopic appendectomy was performed the following day. Chronic thickening of the appendix was seen on gross examination and a pathology report confirmed acute appendicitis. The SBO with multiple bands on the right side of the pelvis was released with no evidence of ischemia throughout the bowel. Adhesions were noted on the right and left lobe of the liver adhering to the abdominal wall and ileal portion of the small bowel. The adhesions were removed during the laparoscopic procedure. Post operatively, gynecology was consulted who recommended changing antibiotics to cefoxitin, doxycycline, and metronidazole.

The adhesions noted during the laparoscopic procedure were concerning for Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome. During the re-interview, the patient endorsed engaging in sexual activity with two male partners. A sexually transmitted infection (STI) panel was sent with appropriate consent. A urine sample was tested for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae by a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), rapid plasma reagin (RPR), and hepatitis panels were sent. She was found to be positive for Chlamydia trachomatis confirming the diagnosis. Pelvic ultrasound demonstrated complex bilateral ovarian cysts and normal reproductive anatomy. The patient was informed about condom use and notifying partners about STIs. Notifications were addressed as per local rules and regulations. A social worker and child protective services were consulted, and their investigation revealed no history of abuse. The patient was noted to have lost 6 kg weight during her prolonged hospitalization and required partial parenteral nutrition.

Follow-up and outcomes

The birth control plan was discussed with the patient in detail. She opted for medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera) contraceptive injection which was given prior to discharge. The patient was discharged from the hospital on an antibiotic regimen consisting of doxycycline and metronidazole, with recommendations to follow up with her primary physician, gynecologist, and surgery team. A primary care physician appointment was scheduled to follow up on STI treatment and further testing.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

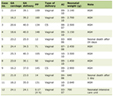

STIs have an incidence of 26 million cases [7] in 2018 alone, with approximately 20 million cases each year. Adolescents and young adult patients aged 15 - 24 years account for more than half of these [7, 8], with 55.4% of the STIs reported in 2019 in this age group. The high rate of STIs in adolescents and young adults is multifactorial. This can be partly explained by the development of genitourinary anatomy. In women specifically, the cervical transitional zone of squamous and columnar epithelium is located on the outer ectocervix, leading to an increased susceptibility to infection. In contrast, in adults, the cervical transition zone is located in the inner endocervical region resulting in more protection [4]. Further studies reveal that teenage females are less likely to adhere to medication regimens and have a higher propensity for recurrent STIs, leading to an increased risk of ectopic pregnancies and infertility [9]. As mentioned by Khine et al [10], in their case series, most of the patients presented to the emergency department with nonspecific abdominal symptoms but as noted in our case, presentation with appendicitis and SBO together was not noted to be reported in the adolescent age group previously (Table 1) [10-12].

Click to view | Table 1. Literature Review of Case Reports Documenting Fitz-Hughs-Curtis Syndrome Complicated by Appendicitis and/or SBO |

The diagnosis of Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome is complex as its presentation may mimic other abdominal disease pathologies. Furthermore, its pathogenesis requires a prior history of chlamydia or gonococcal infection which may present asymptomatically. Other organisms that are associated with Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome are Mycoplasma genitalium, anaerobes such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis and some gram-negative bacteria [13, 14]. Prior case reports conclude that Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome is diagnosed on CT imaging which reveals peritoneum, hepatic capsule, or subcapsular enhancement in the arterial phase [6, 15]. However, our case differs from those, as our patient did not have peritoneal or capsular enhancement on CT findings. In this patient, the diagnosis was particularly difficult due to minimal pelvic inflammatory symptoms, normal liver function tests, and lack of hepatic capsular enhancement on CT imaging. Additionally, our patient did not present with other related symptoms such as urinary frequency or vaginal discharge. Furthermore, Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome may be less likely to be included on a differential for a pediatric patient due to its rarity and its sexually transmitted pathogenesis. Our case highlights the rare situation of a 15-year-old presenting with a combination of SBO and appendicitis.

In addition to ectopic pregnancy and infertility, chronic pelvic pain, and SBO are considered sequelae associated with PID and Fitz-Hughs-Curtis disease [5, 9]. These sequelae can result in decreased quality of life, increased healthcare costs, and mortality. Yeh et al report that young females with PID remain at increased risk of ectopic pregnancy for up to 15 years [16]. Hence, discussing pregnancy prevention measures, and patient education, as was done in our patient, is also important for further long-term risk reduction. As mechanical obstruction is the most common cause of SBO, the intra-abdominal adhesions, found laparoscopically, are hypothesized to be a leading factor in the pathologic development of disease in our patient as the patient had no other identifiable risk factors or prior intra-abdominal surgeries [5].

Furthermore, more accurate imaging diagnostic techniques are needed to assess for Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome pre-operatively. A more precise imaging test can lead to earlier interventions and fewer long-term complications.

This case presentation highlights the need for an increased index of suspicion for Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome in an adolescent female presenting with abdominal pain. When interviewing adolescents, sexual history may be perceived as a sensitive topic, specifically in the presence of parents or guardians. During the initial private interview, our patient denied any sexual history. However, upon finding the adhesions and educating the patient on potential STI pathology, she divulged that she had two sexual male partners. Cultivating a confidential relationship and rapport building with an adolescent is crucial in obtaining an accurate patient history in order to curate a differential diagnosis. Screening for STIs should be obtained if the history indicates an at-risk patient, so as to prevent long-term complications, including but not limited to Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome.

Conclusions

Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome is a rare complication of PID which presents with a wide variety of long-term sequelae. In young female patients presenting with RUQ pain, especially with complications such as SBO, and appendicitis, Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome should be considered a differential diagnosis. Furthermore, additional accurate diagnostic imaging techniques are needed to assess for Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome in the young patient population in order to prevent further complications associated with PID.

Learning points

Although sexually transmitted disease sequelae are rare in adolescents, a differential diagnosis such as Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome should be considered for patients presenting with abdominal pain.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support provided by Inspira Health, NJ in the completion of this article.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

The subject has given informed consent.

Author Contributions

MC contributed to data gathering, literature review and writing. TP contributed to data gathering, writing, revising, and proofreading. RP contributed to literature review, writing and proofreading.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this report are available within the article.

Abbreviations

PID: pelvic inflammatory disease; SBO: small bowel obstruction; STI: sexually transmitted infection; RUQ: right upper quadrant; RLQ: right lower quadrant; CT: computed tomography; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019

| References | ▴Top |

- Wang SP, Eschenbach DA, Holmes KK, Wager G, Grayston JT. Chlamydia trachomatis infection in Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;138(7 Pt 2):1034-1038.

doi - Basit H, Pop A, Malik A, Sharma S. Fitz-Hugh-Curtis Syndrome. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL), 2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499950/.

- Risser WL, Risser JM, Benjamins LJ, Feldmann JM. Incidence of Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome in adolescents who have pelvic inflammatory disease. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2007;20(3):179-180.

doi pubmed - Peter NG, Clark LR, Jaeger JR. Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome: a diagnosis to consider in women with right upper quadrant pain. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;71(3):233-239.

doi pubmed - Al-Ghassab RA, Tanveer S, Al-Lababidi NH, Zakaria HM, Al-Mulhim AA. Adhesive small bowel obstruction due to pelvic inflammatory disease: a case report. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2018;6(1):40-42.

doi pubmed - Cho HJ, Kim HK, Suh JH, Lee GJ, Shim JC, Kim YH. Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome: CT findings of three cases. Emerg Radiol. 2008;15(1):43-46.

doi pubmed - Kreisel KM, Spicknall IH, Gargano JW, Lewis FMT, Lewis RM, Markowitz LE, Roberts H, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among us women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2018. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48(4):208-214.

doi pubmed - Forsyth S, Rogstad K. Sexual health issues in adolescents and young adults. Clin Med (Lond). 2015;15(5):447-451.

doi pubmed - Trent M, Haggerty CL, Jennings JM, Lee S, Bass DC, Ness R. Adverse adolescent reproductive health outcomes after pelvic inflammatory disease. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(1):49-54.

doi pubmed - Khine H, Wren SB, Rotenberg O, Goldman DL. Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome in adolescent females: a diagnostic dilemma. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019;35(7):e121-e123.

doi pubmed - Kazama I, Nakajima T. A case of fitz-hugh-curtis syndrome complicated by appendicitis conservatively treated with antibiotics. Clin Med Insights Case Rep. 2013;6:35-40.

doi pubmed - Ishimaru N, Kanzawa Y, Nakajima T, Seto H, Ando M, Kinami S. Diagnostic challenge of chlamydial Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome and cervicitis complicated by appendicitis: Case report. J Gen Fam Med. 2021;22(5):288-290.

doi pubmed - Amodeo S, Paci G, Cutaia G, Murmura B, Cannizzaro F, Venezia R. Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome secondary to postpartum endometritis: case report and literature review. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2021;10(3):184-186.

doi pubmed - Coremans L, de Clerck F. Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome associated with tuberculous salpingitis and peritonitis: a case presentation and review of literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18(1):42.

doi pubmed - Nishie A, Yoshimitsu K, Irie H, Yoshitake T, Aibe H, Tajima T, Shinozaki K, et al. Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome. Radiologic manifestation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27(5):786-791.

doi pubmed - Yeh JM, Hook EW, 3rd, Goldie SJ. A refined estimate of the average lifetime cost of pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30(5):369-378.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.