| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 13, Number 8, August 2022, pages 374-379

Anti-MDA5 Associated Clinically Amyopathic Dermatomyositis With Rapidly Progressive Interstitial Lung Disease

Kameron Tavakoliana, c, Mihir Odaka, Anton Mararenkoa, Justin Ilagana, Steven Douedia, Taimoor Khanb, Ghadier Al Saoudib

aDepartment of Medicine, Jersey Shore University Medical Center, Neptune City, NJ, USA

bDepartment of Pulmonary and Critical Care, Jersey Shore University Medical Center, Neptune City, NJ, USA

cCorresponding Author: Kameron Tavakolian, Department of Medicine, Jersey Shore University Medical Center, Neptune City, NJ 077543, USA

Manuscript submitted June 1, 2022, accepted July 7, 2022, published online August 19, 2022

Short title: Anti-MDA5 Associated CADM With RP-ILD

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3965

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Anti-melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (anti-MDA5) associated clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis (CADM) is a rare entity that is frequently associated with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease. The disease is characterized by its association with a distinct myositis specific antibody, the lack of muscle involvement seen with other inflammatory myopathies, and a strong correlation with the development of rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease. Diagnosis is based on clinical findings and the presence of autoantibodies. Management generally involves combination immunosuppression therapy. However, the disease course is often aggressive and lends a poor prognosis. We report a case of a healthy 55-year-old male who presented with dyspnea, dry cough, and joint pain for 1 month. The patient was diagnosed with anti-MDA5 associated CADM with interstitial lung disease after a complete rheumatological workup found elevated titers of MDA5 antibodies and computed tomography of the chest without contrast revealed radiographic evidence of interstitial lung involvement. Disease course was complicated by the development of Pneumocystis pneumonia as a result of profound immunosuppression from combination immunosuppressant therapy. Our patient eventually succumbed to his illness approximately 10 weeks following initial symptom onset. This case highlights the aggressive nature of the disease and the challenges in management. Further research is warranted to establish more effective therapeutic options.

Keywords: Anti-MDA antibody; Myositis specific antibody; Idiopathic inflammatory myositis; Clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis; Rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease; Dyspnea; Hypoxia

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis (CADM) is a rare form of idiopathic inflammatory myositis that is frequently associated with autoantibodies against melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5) [1]. Other than its association with a myositis specific antibody, a major distinguishing feature of CADM is the lack of muscle involvement that is typically seen with other inflammatory myopathies [2]. Furthermore, affected individuals are at an increased risk of developing rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease (RP-ILD), leading to significantly higher morbidity and mortality compared to other inflammatory myopathies [1]. Although not fully understood, the pathogenesis of CADM associated ILD (CAMD-ILD) is multifactorial, involving environmental, genetic, and immunological factors leading to compliment and macrophage activation [3, 4]. Therapeutic options are limited and typically involve combination immunosuppression therapy [1]. We present the case of a healthy male with anti-MDA5 associated CADM with RP-ILD highlighting the aggressive disease course, challenges in diagnosis, and difficulties in management.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 55-year-old male with no significant past medical history presented with dyspnea, dry cough, and joint pain that began 1 month prior. His joint pain was diffuse with bilateral distribution in the fingers, hands, wrists, elbows, shoulders, hips, knees, and ankles, which he attributed to several hours spent shoveling snow. Two weeks later, he presented to an urgent care clinic for persistent symptoms, where he was prescribed ibuprofen 6 mg every 6 h as needed, oxycodone-acetaminophen 5 - 325 mg every 6 h as needed, and methylprednisolone 4 mg for 5 days. The patient’s joint pain worsened despite adherence to these medications, and he developed dyspnea with an associated dry cough. After multiple home tests for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) resulted negative, the patient presented to the emergency department for further evaluation. His shortness of breath was worse with exertion, and his joint pain and dry cough had no aggravating or relieving factors. He also noted that he had a 15 lb unintentional weight loss. He denied any fever, headache, sore throat, chest pain, hemoptysis, gastrointestinal symptoms, and calf swelling or pain. Additionally, the patient was a former smoker with a 20-year pack history who quit 10 years prior. He had no history of recent travel, sick contacts, or exposure to occupational or environmental toxic fume. However, he did receive the third dose of the Moderna SARS-CoV-2 vaccine 1 month prior to the onset of his joint pain.

On initial evaluation, vitals were blood pressure 98/63 mm Hg, heart rate 93 beats/min, respirations 18/min, temperature 36.8 °C, and oxygen saturation 93% on room air. He was subsequently placed on 2 L of oxygen via nasal cannula and his oxygen saturation improved to 98%. Physical examination was remarkable for bibasilar rales, tenderness with associated swelling of the fingers, hands, wrists, elbows, shoulders, hips, knees and ankles, erythematous papules on the dorsum of the left hand, and erythematous macules on the fingers of the left hand, left elbow and left knee. No muscle tenderness was appreciated on examination.

Diagnosis

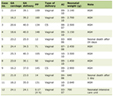

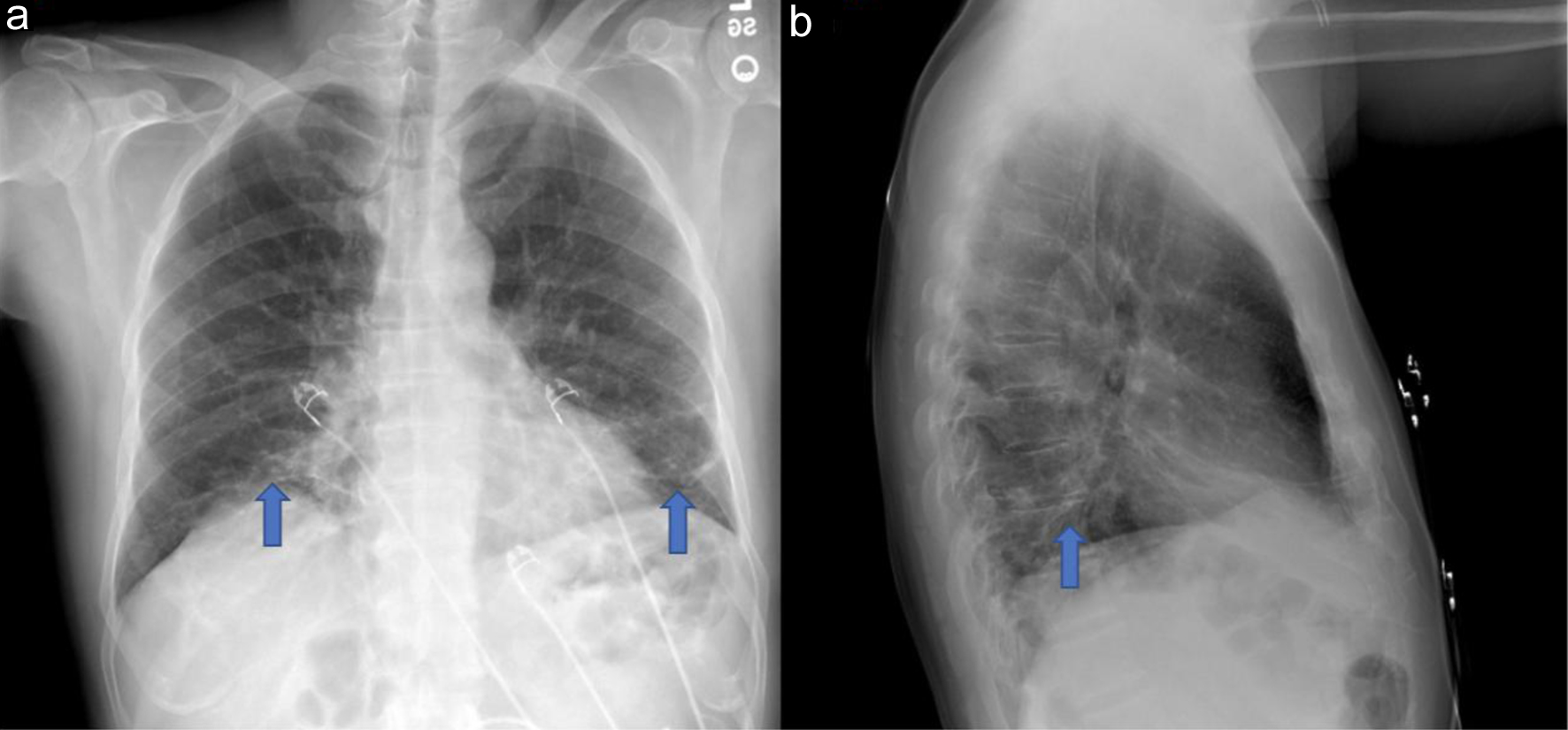

Significant laboratory studies included a D-dimer of 1,702 (reference range: ≤ 500 ng/mL), aspartate aminotransferase of 86 (reference range: 10 - 42 U/L), alanine aminotransferase of 65 (reference range: 10 - 60 U/L), C-reactive protein (CRP) of 3.70 (reference range: 0.00 - 0.74 mg/dL), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 52 (reference range: 0 - 20 mm/h). All other initial laboratory studies including complete blood count, electrolytes, total creatinine kinase, procalcitonin, were within normal limits, and blood cultures, sputum cultures, and respiratory pathogen panel were negative (Table 1). Posteroanterior and lateral chest X-ray (Fig. 1) showed patchy atelectatic changes at bilateral lung bases and computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) of the chest was negative for pulmonary embolism but the lung window (Fig. 2) demonstrated nonspecific patchy areas of atelectasis and increased interstitial markings at bilateral lung bases.

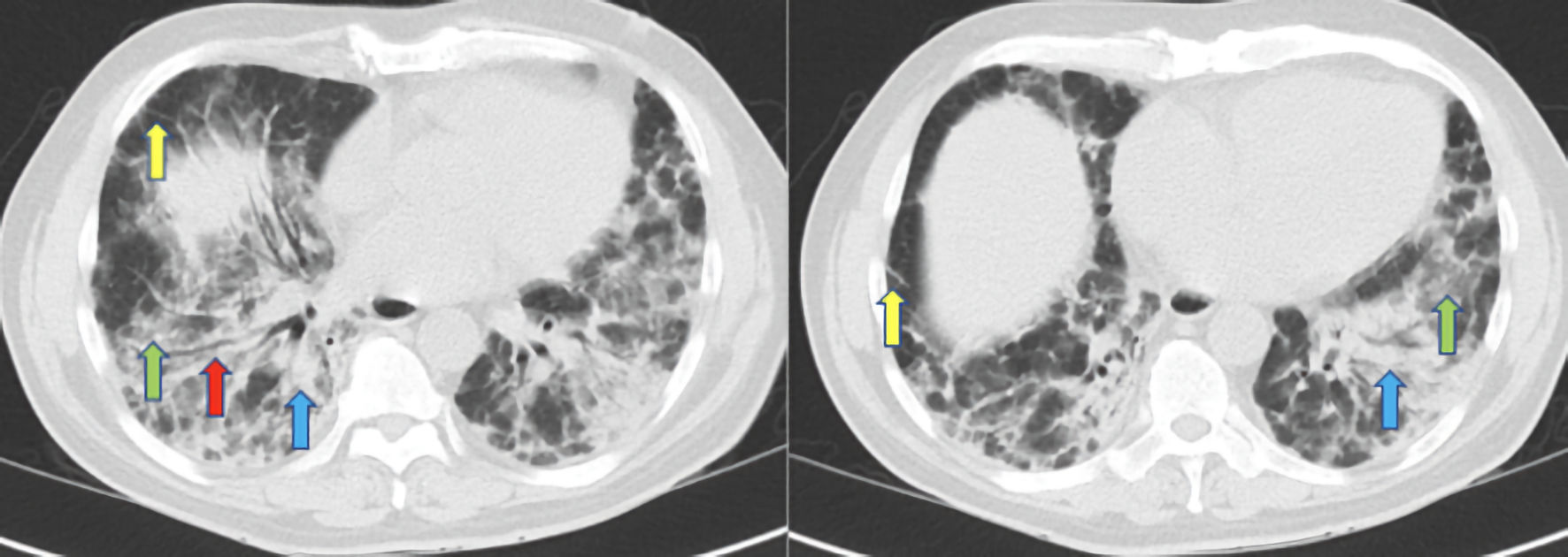

Click to view | Table 1. Initial Laboratory Results |

Click for large image | Figure 1. Posteroanterior (a) and lateral (b) chest X-ray demonstrating patchy atelectatic changes at bilateral lung bases (blue arrow). |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) of the chest in lung window demonstrating septal thickening (yellow arrows) and nonspecific patchy areas of atelectasis and increased interstitial markings at bilateral lung bases (green arrows). |

The patient was subsequently admitted to the hospital and rheumatology and pulmonology consults were placed. A complete infectious and rheumatologic workup was performed including SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction, Streptococcus pneumoniae urine antigen, Legionella urine antigen, antistreptolysin O titer test, acute hepatitis panel, fourth generation human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing, QuantiFERON-TB Gold (a blood test that aids in the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis), Lyme disease antibody, complement levels, antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, human leukocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27) antigen, anticardiolipin antibody, beta-2-glycoprotein antibody, anti-Jo-1 antibody, antideoxyribonuclease B (anti-DNase B) antibody, anti-Smith antibody, anti-ribonucleoprotein antibody, myeloperoxidase antibody, proteinase-3 antibody, topoisomerase I (Scl-70) antibody, anti-Sjogren’s syndrome-related antigen A antibody, anti-Sjogren’s syndrome-related antigen B antibody, ribonucleic acid (RNA) polymerase III antibody, centromere B antibody, cyclic citrullinated antibody, and myositis specific 11 antibody panel including MDA5 antibody.

Treatment

Over the next 3 days, the patient was treated for community acquired pneumonia as well as a presumed autoimmune inflammatory arthropathy with associated ILD with azithromycin 500 mg daily, ceftriaxone 1 g daily, fluticasone-vilanterol inhaler one puff daily, tiotropium bromide two puffs daily, and prednisone 60 mg daily. After significant improvement in the patient’s symptoms, he was transitioned to oral cefuroxime 500 mg twice a day and prednisone 40 mg daily prior to discharge. He was provided follow-up appointments with pulmonology for pulmonary function testing (PFT) and rheumatology to review the extensive in-patient workup.

Follow-up and outcomes

One week after discharge the patient followed up with rheumatology and was diagnosed with CADM with associated ILD, evidenced by elevated anti-MDA5 antibody titers of 72 (reference range: < 11 SI). The patient was started on mycophenolate mofetil 1,000 mg twice a day and prednisone 60 mg daily with a slow taper. At his follow-up appointment with pulmonology, a 6-min walk test was normal and PFT was consistent with mild asthma. He was diagnosed with asthma and mild ILD and started on fluticasone-salmeterol and tiotropium bromide. In addition, a prescription for a repeat chest X-ray to be done 4 - 6 weeks later was provided.

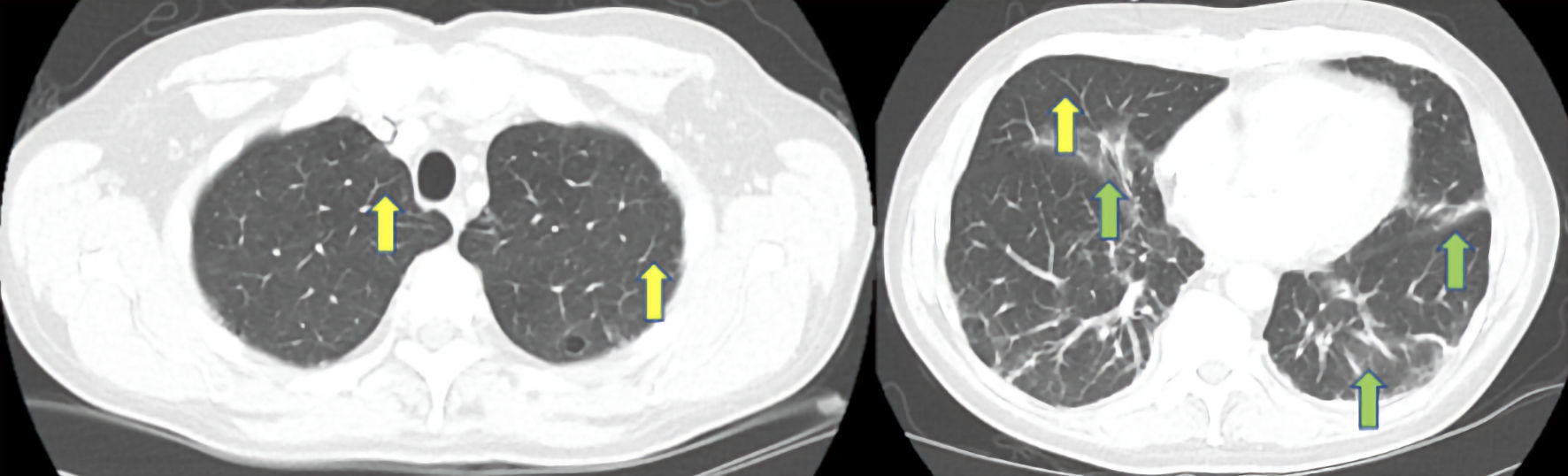

Approximately 5 weeks after his initial presentation, the patient complained of a new cough with foamy, non-bloody sputum production. Outpatient bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and transbronchial biopsy of the left lower lobe was performed. After the procedure, the patient was noted to have a fever of 40.3 °C and was subsequently readmitted for further evaluation and to rule out sepsis. At this point, there was a concern for infection in the setting of immunosuppression. Blood cultures, sputum cultures, and (1,3)-beta-D-glucan were sent in addition (BAL) studies. The patient was started on vancomycin 1.25 g every 12 h, piperacillin-tazobactam 3.375 g every 8 h, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim 800 mg/160 mg two tablets every 8 h, and methylprednisone 40 mg every 12 h. High resolution CT scan of the chest (Fig. 3) revealed traction bronchiectasis and interval worsening of bilateral mixed interstitial alveolar infiltrates, ground glass opacities, and septal thickening.

Click for large image | Figure 3. High resolution CT scan of the chest demonstrating traction bronchiectasis (red arrow), bilateral mixed interstitial and alveolar infiltrates (blue arrows), ground glass opacities (green arrows), and septal thickening (yellow arrows). CT: computed tomography. |

Over the following 6 days, the patient’s clinical status continued to deteriorate, and he had increasing supplemental oxygen requirements for persistent hypoxia with an oxygen saturation ranging between 82% and 95%. Transbronchial biopsy results revealed normal lung tissue. However, results from the BAL were positive for Pneumocystis jirovecii and he was diagnosed with Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), likely due to recent initiation of immunosuppressive therapy for CADM, associated with a RP-ILD. The patient was transferred to the medical intensive care unit for close monitoring. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was changed from oral to intravenous 5 mg/kg every 6 h and plasma exchange therapy was initiated. The patient’s hypoxia worsened despite the use of bilevel positive airway pressure, and he was subsequently intubated. Furthermore, intubation was complicated by the development of pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum. Cardiothoracic surgery was consulted and recommended against chest tube placement given the small size of the pneumothorax. After several days of full ventilator support and initiation of titratable intravenous norepinephrine, the patient deteriorated into pulseless electrical activity (PEA) arrest, and ultimately succumbed to his condition.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Dermatomyositis (DM) is a form of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy that generally involves the skin and muscles. Similar to other connective tissue disorders, there is a well-known association between DM and ILD. A rare subtype of the disease known as CADM is associated with anti-MDA5 antibody and presents without muscle findings [2].

CADM is associated with an increased risk of developing ILD and more specifically, RP-ILD, leading to increased morbidity and mortality in affected individuals [1]. One meta-analysis found that the presence of anti-MDA5 antibodies had a sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 86% for the development of RP-ILD, with an associated mortality of 59% [5]. A retrospective study evaluating patients with DM associated ILD (DM-ILD) and CADM associated ILD (CADM-ILD) found mortality to be 6% and 45%, respectively [6]. Furthermore, the study found that patients with CADM-ILD had a shorter duration of symptoms prior to hospital admission, suggesting that these patients had a more rapidly progressive form of disease.

The diagnosis of CADM can be a challenging process for clinicians, as diagnostic and classification criteria have changed numerous times throughout history. The first major diagnostic criteria were established in 1975 by Bohan and Peter; however, diagnosis could not be made without muscle involvement [7, 8]. In 2017, the first validated criteria created by the European League Against Rheumatism and American College of Rheumatology was established, which includes three skin findings: heliotrope rash, Gottron papules, and Gottron sign, with two findings required to establish a diagnosis [9]. However, several cases of CADM in the absence of cutaneous manifestations have been reported, adding to the diagnostic challenge [10]. To our knowledge, there are no specific histological or radiological findings unique to CADM-ILD that aid in its diagnosis.

Aggressive and early treatment with the use of multiple immunosuppressive agents is essential in the management of CADM-ILD. First line therapy involves high-dose glucocorticoids combined with calcineurin inhibitors, with or without cyclophosphamide [11]. A multicenter prospective study in Japan found that patients treated initially with a combination of high-dose glucocorticoids, calcineurin inhibitors, and cyclophosphamide had a 6-month survival rate of 89%, compared to 33% in patients treated with a step-up strategy starting with high-dose glucocorticoids [12]. A retrospective study in Japan reproduced these results; however, they reported frequent cytomegalovirus reactivation secondary to severe immunosuppression [13]. For patients unable to tolerate calcineurin inhibitors, mycophenolate mofetil and biological therapies may be considered [11].

Two other biologic therapies that have shown to be equally effective, if not superior to triple immunosuppressive therapy, are basiliximab and tofacitinib [14-16]. One open label clinical study [16] evaluated the use of tofacitinib in conjunction with glucocorticoids compared to a historical control group who received stepwise base immunotherapy. The study found a significantly improved 6-month mortality in the tofacitinib group of 100% compared to 78% in the control group. Furthermore, this mortality benefit was seen in the absence of profound immunosuppression, minimizing the risk of opportunistic infection. Another biologic agent approved for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, pirfenidone, may have a role in the treatment of CADM with subacute ILD [17].

Refractory disease is defined as lack of clinical response to combined immunosuppression, including glucocorticoids, after 1 week of therapy [11]. Therapeutic options for these patients include addition of a third immunosuppressant (if only on dual therapy) or using a different combination of immunotherapy [11]. Nonpharmacological rescue therapies in critically ill patients include plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulin, venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and lung transplantation [11]. Two studies in Japan reported significant mortality benefit in patients who received plasmapheresis in combination with immunosuppression therapy compared to immunosuppression therapy alone [18, 19]. While preliminary data on the use of plasmapheresis is promising, further research is warranted to assess the benefit of other nonpharmacological rescue therapies.

Our previously healthy, young patient succumbed to his illness 10 weeks following his diagnosis. Furthermore, the lack of muscle involvement in our patient in the setting of elevated anti-MDA5 titers in conjunction with a RP-ILD phenotype supports the literature regarding CADM-ILD. Profound immunosuppression from combination immunotherapy and the subsequent development of PCP likely hastened the respiratory failure seen in our patient. Reflecting retrospectively, we ponder if the use of a biologic agent or early initiation of plasmapheresis may have led to a better outcome for our patient. This case illustrates the rapid progression of CADM-ILD, as well as the associated complications with treatment.

Learning points

Anti-MDA5 antibody associated CADM-ILD is a rare disease associated with poor outcomes. Effective management is dependent on early diagnosis and aggressive treatment. Additionally, myositis specific antibodies have been shown to provide valuable diagnostic and prognostic information to clinicians. When treating patients with CADM-ILD, clinicians must maintain a high suspicion for opportunistic infections. More research is warranted in order to develop more effective diagnostic methods and therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient’s family before the presentation of this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Each author has been individually involved in and has made substantial contributions to conceptions and designs, acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting, and editing the manuscript. KT contributed to the designs, acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting, and editing of the manuscript. MO, AM and JI contributed to the drafting and editing of the manuscript. SD and TK contributed to design and editing of the manuscript. GAS contributed to the analysis and editing of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Kersey CB, Oshinsky C, Wahl ER, Newman TA. Anti-MDA5 antibody-associated clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis: case report and literature review. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(12):3865-3868.

doi pubmed - Sato S, Hirakata M, Kuwana M, Suwa A, Inada S, Mimori T, Nishikawa T, et al. Autoantibodies to a 140-kd polypeptide, CADM-140, in Japanese patients with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(5):1571-1576.

doi pubmed - Gono T, Miyake K, Kawaguchi Y, Kaneko H, Shinozaki M, Yamanaka H. Hyperferritinaemia and macrophage activation in a patient with interstitial lung disease with clinically amyopathic DM. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(7):1336-1338.

doi pubmed - DeWane ME, Waldman R, Lu J. Dermatomyositis: Clinical features and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(2):267-281.

doi pubmed - Chen Z, Cao M, Plana MN, Liang J, Cai H, Kuwana M, Sun L. Utility of anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody measurement in identifying patients with dermatomyositis and a high risk for developing rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease: a review of the literature and a meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(8):1316-1324.

doi pubmed - Mukae H, Ishimoto H, Sakamoto N, Hara S, Kakugawa T, Nakayama S, Ishimatsu Y, et al. Clinical differences between interstitial lung disease associated with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis and classic dermatomyositis. Chest. 2009;136(5):1341-1347.

doi pubmed - Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1975;292(7):344-347.

doi pubmed - Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (second of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1975;292(8):403-407.

doi pubmed - Lundberg IE, Tjarnlund A, Bottai M, Werth VP, Pilkington C, Visser M, Alfredsson L, et al. 2017 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(12):1955-1964.

doi pubmed - Gonzalez-Moreno J, Raya-Cruz M, Losada-Lopez I, Cacheda AP, Oliver C, Colom B. Rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease due to anti-MDA5 antibodies without skin involvement: a case report and literature review. Rheumatol Int. 2018;38(7):1293-1296.

doi pubmed - Selva-O'Callaghan A, Romero-Bueno F, Trallero-Araguas E, Gil-Vila A, Ruiz-Rodriguez JC, Sanchez-Pernaute O, Pinal-Fernandez I. Pharmacologic treatment of anti-MDA5 rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease. Curr Treatm Opt Rheumatol. 2021;7(4):319-333.

doi pubmed - Tsuji H, Nakashima R, Hosono Y, Imura Y, Yagita M, Yoshifuji H, Hirata S, et al. Multicenter prospective study of the efficacy and safety of combined immunosuppressive therapy with high-dose glucocorticoid, tacrolimus, and cyclophosphamide in interstitial lung diseases accompanied by anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5-positive dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(3):488-498.

doi pubmed - Matsuda KM, Yoshizaki A, Kuzumi A, Fukasawa T, Ebata S, Yoshizaki-Ogawa A, Sato S. Combined immunosuppressive therapy provides favorable prognosis and increased risk of cytomegalovirus reactivation in anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis. J Dermatol. 2020;47(5):483-489.

doi pubmed - Zou J, Li T, Huang X, Chen S, Guo Q, Bao C. Basiliximab may improve the survival rate of rapidly progressive interstitial pneumonia in patients with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis with anti-MDA5 antibody. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(8):1591-1593.

doi pubmed - Kurasawa K, Arai S, Namiki Y, Tanaka A, Takamura Y, Owada T, Arima M, et al. Tofacitinib for refractory interstitial lung diseases in anti-melanoma differentiation-associated 5 gene antibody-positive dermatomyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57(12):2114-2119.

doi pubmed - Chen Z, Wang X, Ye S. Tofacitinib in amyopathic dermatomyositis-associated interstitial lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(3):291-293.

doi pubmed - Li T, Guo L, Chen Z, Gu L, Sun F, Tan X, Chen S, et al. Pirfenidone in patients with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease associated with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33226.

doi pubmed - Shirakashi M, Nakashima R, Tsuji H, Tanizawa K, Handa T, Hosono Y, Akizuki S, et al. Efficacy of plasma exchange in anti-MDA5-positive dermatomyositis with interstitial lung disease under combined immunosuppressive treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59(11):3284-3292.

doi pubmed - Abe Y, Kusaoi M, Tada K, Yamaji K, Tamura N. Successful treatment of anti-MDA5 antibody-positive refractory interstitial lung disease with plasma exchange therapy. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59(4):767-771.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.