| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 14, Number 5, May 2023, pages 155-161

Boon or Bane? Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy Complicated by Listeria monocytogenes Meningitis Culminating in Colectomy for Ulcerative Colitis

Ria Nagpala, b , Hemnaath Ulaganathana, b, Khushal Khana, Brian Egana

aDepartment of Gastroenterology, Mayo University Hospital, Castlebar, County Mayo, Ireland

bCorresponding Author: Ria Nagpal and Hemnaath Ulaganathan, Department of Gastroenterology, Mayo University Hospital, Castlebar, County Mayo, Irelandand

Manuscript submitted February 22, 2023, accepted April 26, 2023, published online May 31, 2023

Short title: Anti-TNF Therapy in Colectomy for UC

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc4041

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) biologics have revolutionized the management of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) by promoting mucosal healing and delaying surgical intervention in ulcerative colitis (UC). However, biologics can potentiate the risk of opportunistic infections alongside the use of other immunomodulators in IBD. As recommended by the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO), anti-TNF-α therapy should be suspended in the setting of a potentially life-threatening infection. The objective of this case report was to highlight how the practice of appropriately discontinuing immunosuppression can exacerbate underlying colitis. We need to maintain a high index of suspicion for complications of anti-TNF therapy, so that we can intervene early and prevent potential adverse sequelae. In this report, a 62-year-old female presented to the emergency department with non-specific symptoms including fever, diarrhea and confusion on a background of known UC. She had been commenced on infliximab (INFLECTRA®) 4 weeks earlier. Inflammatory markers were elevated, and Listeria monocytogenes was identified on both blood cultures and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The patient improved clinically and completed a 21-day course of amoxicillin advised by microbiology. After a multidisciplinary discussion, the team planned to switch her from infliximab to vedolizumab (ENTYVIO®). Unfortunately, the patient re-presented to hospital with acute severe UC. Left-sided colonoscopy demonstrated modified Mayo endoscopic score 3 colitis. She has had recurrent hospital admissions over the past 2 years for acute flares of UC, ultimately culminating in colectomy. To our knowledge, our case-based review is unique in unpacking the dilemma of holding immunosuppression at the risk of IBD worsening.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis; Inflammatory bowel disease; Anti-TNF therapy; Infliximab; Listeria monocytogenes; Vedolizumab; Meningitis; Colectomy

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Listeria monocytogenes is a Gram-positive, intracellular bacterium that is encountered commonly in older adults and the immunocompromised. In the adult patient cohort, central nervous system infection leading to meningitis is clinically one of the most commonly seen manifestations of Listeria infection [1, 2]. The incidence rate of listeriosis in those on anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α therapy is around three cases per 10,000 patient-years, significantly higher than in the general population [2].

TNF is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The inflamed bowel mucosa is made up of a variety of stromal and immune cells that produce both soluble and membrane-bound TNF, along with other pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6 and IL-18 [3]. Hence, TNF inhibitors are a clinically effective option in the treatment of several chronic inflammatory disorders making it even more important for clinicians to be aware of their risks. These agents essentially alter the natural course of ulcerative colitis by encouraging mucosal healing and delaying potential colectomy [4]. There are multiple case reports detailing the development of opportunistic infections associated with anti-TNF therapy. Examples of opportunistic infections described in the literature include tuberculosis, listeriosis, Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia and viral or invasive fungal infections [5].

This report explores the rationale, risks and benefits of anti-TNF therapy through a case where infliximab was introduced as rescue therapy for steroid-unresponsive ulcerative colitis (UC). This is one of the few case-based reviews on listeriosis in patients on anti-TNF therapy to present a conundrum with regards to immunosuppression. Most case reports reviewed as part of this article demonstrate the potential severity and heterogeneity of L. monocytogenes infection (Supplementary Material 1, www.journalmc.org). Primary teams generally had to commence the patient on an extended course of antibiotics and consider alternative immunosuppression or reintroduce the same agent once their patient was more stable. However, what makes our report stand out is the “domino effect” of listeriosis where severe infection compels the clinician to hold immunosuppressants only to lead to worsening colitis.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

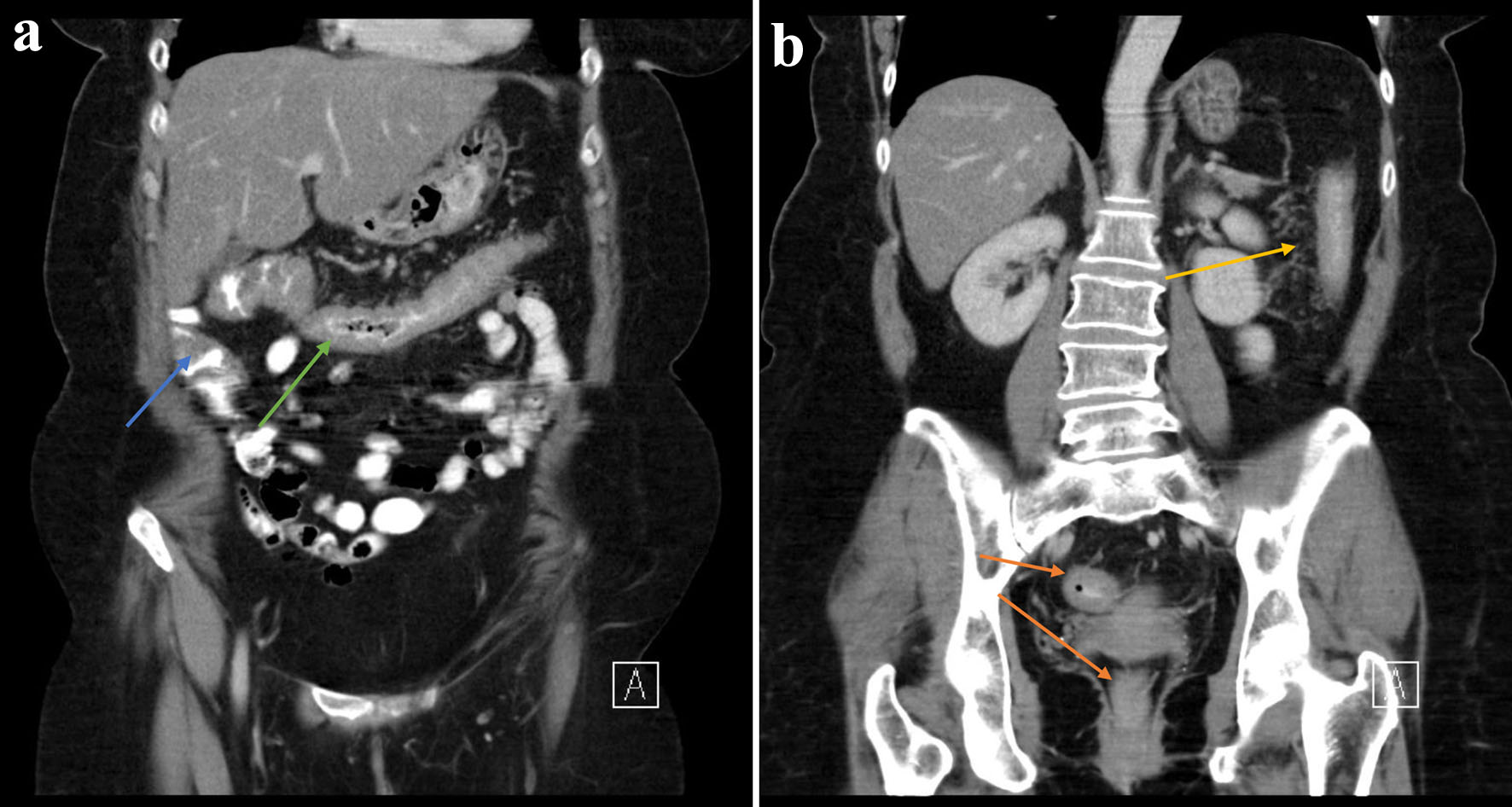

We hereby present a case of a 62-year-old female with a history of UC first diagnosed in December 2020, initially maintained with 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA). She had an acute severe flare of UC in August 2021 which prompted initiation of infliximab with a 10 mg/kg loading dose (week 0, 2, 6 and 8). Computed tomography (CT) findings show significant colonic inflammation (Fig. 1a, b). Other investigations included positive serology for perinuclear anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA) and antinuclear antibody (ANA). She had a prior history of breast carcinoma and a family history of UC.

Click for large image | Figure 1. (a, b) There is circumferential thickening of the distal ascending (blue arrow), transverse (green arrow), descending (yellow arrow) and rectosigmoid colon (orange arrow) in keeping with colitis. |

The patient received two infliximab infusions at week 0 and 2 and re-presented to the emergency department with fever, cough, vomiting and diarrhea associated with generalized weakness, confusion and lethargy. On examination, her Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score was low (12/15) with acutely altered mental status and mild neck stiffness. General examination was unremarkable. Along with baseline bloods, a chest X-ray was performed and a full septic screen including blood and urine cultures was sent. C-reactive protein was elevated at 94 mg/dL (normal range 0 - 5 mg/dL). Hemoglobin was stable at 12.8 g/dL (normal range 12 - 15 g/dL). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)) was not detected. Chest X-ray demonstrated a lower respiratory tract infection and she was commenced on broad-spectrum intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam (Tazocin) as well as fluids.

Due to new-onset confusion and persistent hypotension, she was admitted to the intensive care unit. Shortly after admission, her blood cultures were positive for L. monocytogenes. There was no acute intracranial pathology detected on the brain CT with normal parenchymal brain appearances reported (Fig. 2). Neck stiffness is a red flag symptom for meningeal irritation and hence a lumbar puncture was performed.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Computed tomography of brain (09/10/2021) demonstrating normal parenchymal appearances. Lumbar puncture revealed grossly cloudy cerebrospinal fluid with massively elevated white blood cell count of 1,600/mm3, with 70% polymorphonuclear neutrophils and 30% mononuclear cells. No organisms were seen on gram stains with no growth on cultures but Listeria monocytogenes DNA was detected via polymerase chain reaction. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) glucose was low at 1.8 mmol/L (2.22 to 4.44) and CSF protein was raised at 1.75 g/L (0.15 to 0.6) which confirmed a bacterial meningitis. Apart from bacteremia and meningitis, there were no other manifestations of listeriosis in this patient. |

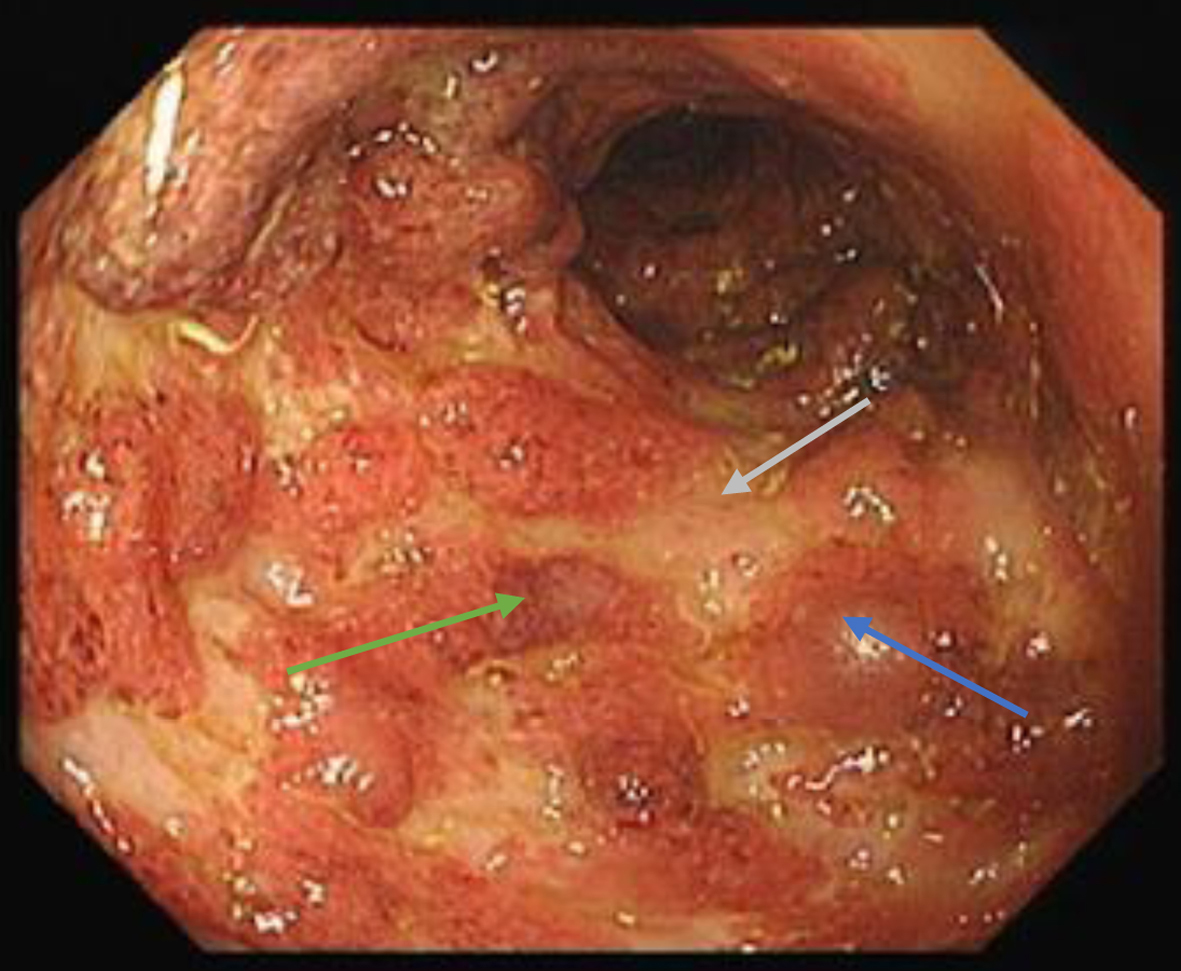

After appropriate inpatient management, she suffered a flare of colitis 2 months later which showed Mayo 3 endoscopic appearance (Fig. 3).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Endoscopic photograph of sigmoid - edematous mucosa (blue arrow), erosions (green arrow) and ulcerations (grey arrow). Also note absence of vascular pattern with marked erythematous appearances. |

Diagnosis

Her initial diagnosis was an acute severe UC. She received high-dose immunosuppression with infliximab thereafter and developed L. monocytogenes sepsis with meningeal involvement.

Treatment

With the diagnosis of L. monocytogenes septicemia, her infliximab was held and was started on a 21-day course of intravenous amoxicillin. After completing the antibiotic course, infliximab was discontinued (third induction dose was not administered).

Follow-up and outcomes

The patient recovered from L. monocytogenes meningitis and was followed up in the outpatient clinic. Vedolizumab, an α4β7 integrin antagonist, was commenced in November 2021 after discussion with multidisciplinary team (MDT) as a more gut selective biological agent. During this period, the option of a colectomy was discussed with her at several points but was declined.

Unfortunately, she presented again with an acute flare of severe UC 2 months later with Mayo 3 on endoscopy. Upon discussion with MDT, she was a suitable candidate for colectomy due to severe pancolitis, recurrent flares and recent sepsis while on biological therapy. She underwent a subtotal colectomy and had an unremarkable post-surgical course.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

IBD patients on immunosuppression are at increased risk of opportunistic infections compared to the general population. This risk may be further compounded by a patient’s comorbidities or advanced age. An opportunistic infection is often described as a microbial infection that is non-pathogenic in the general population but occurs with increasing frequency and severity in patients with a weakened immune system either due to their underlying disease or its management [6]. This case is important because it encourages clinicians to remain vigilant for opportunistic infections in IBD patients on potent immunosuppression. It also raises awareness of the importance of tuberculosis and virology testing before the initiation of anti-TNF biologics. We highlight such infections as a key safety issue and discuss how we can better handle them in clinical practice. Early recognition and prompt workup is imperative to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with pathogens like L. monocytogenes. ECCO guidance recommends the discontinuation of anti-TNF-α biologics during infection with Listeria monocytogenes [7]. As seen in the case described above, the consequent decision to withhold immunosuppression runs the risk of relapse of inflammatory colitis. Such inflammatory exacerbations often call for a multidisciplinary team approach, and at times, escalation to surgical management.

We searched PubMed using the search terms “listeria” and “TNF”. A total of 522 results were generated. Additional reports and articles were identified by reading the literature found via electronic searches, of which 25 articles were examined for existing knowledge on this subject as well as clinical learning points. Other articles were excluded due to either pathophysiology dominant content or because they were unrelated to the topic at hand. There were only three articles excluded due to non-English language. Our literature review is not exhaustive but comprised of the most relevant case reports published to date regarding listeriosis in patients commenced on anti-TNF agents (Supplementary Material 1, www.journalmc.org) [2, 8-31].

We included 25 articles in our review which discussed a total of 44 cases. Of note, we also included a case report of pseudomonas meningitis during vedolizumab treatment. Listeria infections related to immunosuppression presented as meningitis in 23 cases (53.5%), isolated bacteremia in 11 cases (25.6%), and brain abscess in two cases. Other sites of infections also included cerebritis, rhombencephalitis, ankle osteomyelitis, endocarditis, terminal ileitis, septic joint arthritis and gallbladder infections. This demonstrates the heterogeneity of listeriosis leading to variable patient presentations, thereby highlighting the high index of suspicion we need to maintain for such opportunistic infections in patients with risk factors. Seventeen patients (38.6%) had UC, 11 (25%) patients had Crohn’s disease (CD), and 13 (29.5%) had rheumatoid arthritis. There was one case of multiple myeloma as well as psoriatic arthritis. Thirty-five case reports featured the use of infliximab. Where infliximab was commenced, 21 cases (60%) developed symptoms of infection after 1 - 2 doses. Nearly all of the reported cases had concomitant immunosuppression on board such as corticosteroids, azathioprine or mercaptopurine which further rendered these patients vulnerable to opportunistic infections (Supplementary Material 1, www.journalmc.org).

Immunosuppressants such as anti-TNF therapy, corticosteroids, mercaptopurine and azathioprine have become the mainstay of management in IBD. Anti-TNF therapy is also used widely for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis (Supplementary Material 1, www.journalmc.org).

Most patients diagnosed with listeriosis tend to have an invasive infection, meaning the bacteria can potentially spread from their intestines to the blood, causing severe bloodstream infections [32]. The World Health Organisation recognizes the following as risk factors for listeria: pregnancy, patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), cancer and hematological malignancies like leukemia, solid organ transplant recipients or a background of chronic steroid use [33].

The patient was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2018 for which she underwent resection and received chemotherapy and radiotherapy. She was also more susceptible to opportunistic infections due to the recent initiation of anti-TNF-α therapy and recurrent admissions where concomitant high-dose steroids were prescribed for flares of acute severe UC. These vulnerable patient groups should be advised to avoid high-risk meat products such as deli meat as well as supermarket processed meats - this may include cured, cooked and/or fermented sausages and meats, unpasteurised dairy products and cold-smoked fish [33].

In this case, two biologics were featured - infliximab and vedolizumab. Infliximab is a mouse/human chimeric immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) monoclonal antibody that specifically targets the cytokine TNF-alpha. In the European Union, it is licensed for the management of IBD, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriasis as well as psoriatic arthritis [34]. Vedolizumab is a monoclonal antibody with α4β7 integrin antagonist activity. It is a humanized monoclonal antibody with selectivity for the gut that is indicated for use in adults with moderate to severe UC or CD. This is seen being used in clinical practice for patients who either had an inadequate response to, experienced disease relapse, or had intolerance to either conventional UC or CD management or a TNF-alpha inhibitor [35].

The above patient’s treatment for UC was escalated to infliximab (second-line rescue therapy) and eventual surgical intervention in accordance with the guidance provided by the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) [36]. Although she refused colonoscopy at the index admission, CT imaging at the time demonstrated circumferential thickening of the distal ascending, transverse, descending and rectosigmoid colon in keeping with colitis. The extensive nature of her colitis in conjunction with the prolonged duration of bloody diarrhea and abdominal pain warranted the use of oral 5-ASA (mesalazine) and steroids [37]. She was later escalated to anti-TNF therapy due to frequent flares.

There is ongoing debate surrounding the optimal dosing of infliximab as rescue therapy in acute severe colitis. The British Society of Gastroenterology recommends an initial dose of 5 mg/kg infliximab as second-line therapy [38]. Induction with an “intensified” regimen has been explored in one of two ways: either through 1) higher infliximab concentrations or through 2) an accelerated infliximab dosing strategy. There is some evidence that during periods of severe inflammation, there is increased infliximab clearance due to factors such as inflammatory burden, fecal loss and generation of anti-drug antibodies. Further, case-control and case series level data have revealed that an intensified induction strategy may reduce colectomy rates in the short term after an acute exacerbation of UC [39]. This is one of the reasons why some clinicians have adopted the 10 mg/kg dose as “salvage” therapy; however, there is insufficient data to make a recommendation [38].

Surgical management is indicated in UC where patients have disease refractory to medical therapy or have intolerable adverse effects to medications. Other surgical indications also include toxic megacolon, perforation or life-threatening bleeding. In the acute setting, a subtotal colectomy with formation of an end ileostomy with long rectal stump is generally recommended. The gold standard would be a proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) which has been shown to generate satisfactory patient outcomes. It is avoided in the emergency setting as there is a higher risk of surgical complications [38]. In this case, the patient underwent a subtotal colectomy as an intermediate procedure for severe pancolitis and recurrent disease flares.

Serious and opportunistic infections should be on our diagnostic radar even before we commence immunomodulator therapy in IBD. It is important to screen patients for viral infections such as hepatitis, HIV, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), varicella-zoster virus (VZV) as well as tuberculosis and recommend vaccination and prophylaxis as appropriate [6]. In a patient with acute severe colitis, immunosuppression plays a significant role in their management but they also potentiate severe infections and septicemia. However, if stopped or held during infections, the patient can develop worsening colitis culminating in colectomy. In conclusion, we should aim for more rigorous pre-biological screening, patient education about high-risk foods and better recognition and prompt management of both opportunistic infections and acute severe colitis.

Learning points

Our review demonstrates the risks of opportunistic infections with anti-TNF therapy and the importance of counselling patients before initiation of immunomodulators about the avoidance of high-risk foods for listeriosis such as soft cheeses and unpasteurized milk. In addition, we should be wary of holding immunosuppression in patients with severe colitis - worsening colitis may lead to need for future colectomy. Lastly, it is important to consider a patient’s immune risk profile (i.e., underlying malignancy, comorbidities, older adults, obesity, diabetes, etc.) when commencing immunosuppression - this may guide dosing and also encourage early and close surveillance of high-risk patients.

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. Review of Reported Listeria Infections Under Biological Drugs

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent has been obtained.

Author Contributions

Manuscript draft: Ria Nagpal. Manuscript review and editing: Hemnaath Ulaganathan and Ria Nagpal. Literature review: Ria Nagpal. Acquisition of data: Khushal Khan and Hemnaath Ulaganathan.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Doganay M. Listeriosis: clinical presentation. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;35(3):173-175.

doi pubmed - Abreu C, Magro F, Vilas-Boas F, Lopes S, Macedo G, Sarmento A. Listeria infection in patients on anti-TNF treatment: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7(2):175-182.

doi pubmed - Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn WJ, Panaccione R, Domenech E, Pouillon L, Siegmund B, Danese S, et al. Tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in inflammatory bowel disease: the story continues. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:17562848211059954.

doi pubmed pmc - Kuehn F, Hodin RA. Impact of modern drug therapy on surgery: ulcerative colitis. Visc Med. 2018;34(6):426-431.

doi pubmed pmc - Orenstein R, Matteson E. Opportunistic infections associated with TNF-α treatment. Future Rheumatology. 2007;2(6):567-576

- Kucharzik T, Ellul P, Greuter T, Rahier JF, Verstockt B, Abreu C, Albuquerque A, et al. ECCO guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and management of infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(6):879-913.

doi pubmed - Rahier JF, Magro F, Abreu C, Armuzzi A, Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y, Cottone M, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(6):443-468.

doi pubmed - Parihar V, Maguire S, Shahin A, Ahmed Z, O'Sullivan M, Kennedy M, Smyth C, et al. Listeria meningitis complicating a patient with ulcerative colitis on concomitant infliximab and hydrocortisone. Ir J Med Sci. 2016;185(4):965-967.

doi pubmed - Inoue T, Itani T, Inomata N, Hara K, Takimoto I, Iseki S, Hamada K, et al. Listeria monocytogenes septicemia and meningitis caused by listeria enteritis complicating ulcerative colitis. Intern Med. 2017;56(19):2655-2659.

doi pubmed pmc - Rana F, Shaikh MM, Bowles J. Listeria meningitis and resultant symptomatic hydrocephalus complicating infliximab treatment for ulcerative colitis. JRSM Open. 2014;5(3):2054270414522223.

doi pubmed pmc - Issa I, Eid A. Listeria meningitis after infliximab in ulcerative colitis: does the risk of treatment outweigh the benefit. British Journal of Medicine and Medical Research. 2013;3(4):2008-2016.

- Gray J, Allen P, Diong K, Kane M, Varghese A. A case series of listeria monocytogenes infection in inflammatory bowel disease patients treated with anti-TNFα therapy. Gut. 2013;62(Suppl 2):A20.2-A20.

- Katsanos K, Kostapanos M, Zois C, Vagias I, Limberopoulos E, Christodoulou D, et al. Letter to the Editor - Listeria monocytogenes infection two days after infliximab initiation in a patient with ulcerative colitis. Annals of Gastroenterology. 2010;23(3):209-210.

- Williams G, Khan AA, Schweiger F. Listeria meningitis complicating infliximab treatment for Crohn's disease. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16(5):289-292.

doi pubmed pmc - Lamdhade SJ, Thussu A, Al Benwan KO, Alroughani R. Successful treatment of listeria meningitis in a pregnant woman with ulcerative colitis receiving infliximab. General Medicine: Open Access. 2013;1:116.

doi - Rani U, Rana A. Listeria monocytogenes meningitis after treatment with infliximab in an 8-year-old pediatric patient with Crohn's disease. ACG Case Rep J. 2021;8(7):e00624.

doi pubmed pmc - Slifman NR, Gershon SK, Lee JH, Edwards ET, Braun MM. Listeria monocytogenes infection as a complication of treatment with tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agents. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(2):319-324.

doi pubmed - Power D, Jackson L, Murphy O, McCarthy J, Horgan M. Double trouble: pneumocystis pneumonia and listeria meningitis in a patient treated with infliximab for ulcerative colitis - ISG | The Irish Society of Gastoenterology [Internet]. ISG | The Irish Society of Gastoenterology. 2016. Available from: https://isge.ie/abstracts/double-trouble-pneumocystis-pneumonia-listeria-meningitis-patient-treated-infliximab-ulcerative-colitis/.

- Koklu H, Kahramanoglu Aksoy E, Ozturk O, Gocmen R, Koklu S. An unusual neurological complication in a patient with ulcerative colitis. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;28(2):137-139.

doi pubmed - Lee J, Song H, Boo S, Na S, Kim H. Listeria monocytogenes sepsis and meningitis after infliximab treatment for steroid refractory ulcerative colitis. Gut and Liver: Korea Digestive Disease Week. 2019;13(6 Suppl 1):173.

- Reilly E, Hwang J. Listeria cerebritis with tumor necrosis factor inhibition. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2020;2020:4901562.

doi pubmed pmc - Tsuchiya A, Terai S. Listeria meningitis during infliximab-based treatment for ulcerative colitis. Intern Med. 2018;57(17):2603.

doi pubmed pmc - Stratton L, Caddy G. Listeria rhombencephalitis complicating anti-TNF treatment during an acute flare of Crohn’s colitis. Case Reports in Gastrointestinal Medicine. 2016;2016:1-3.

- Atsawarungruangkit A, Dominguez F, Borda G, Mavrogiorgos N. Listeria monocytogenes brain abscess in Crohn’s disease treated with adalimumab. Case Reports in Gastroenterology. 2017;11(3):675-679.

- Bowie VL, Snella KA, Gopalachar AS, Bharadwaj P. Listeria meningitis associated with infliximab. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(1):58-61.

doi pubmed - Kesteman T, Yombi JC, Gigi J, Durez P. Listeria infections associated with infliximab: case reports. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(12):2173-2175.

doi pubmed - Horigome R, Sato H, Honma T, Terai S. Septicemic listeriosis during adalimumab- and golimumab-based treatment for ulcerative colitis: case presentation and literature review. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2020;13(1):22-25.

doi pubmed - Chuang MH, Singh J, Ashouri N, Katz MH, Arrieta AC. Listeria meningitis after infliximab treatment of ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50(3):337-339.

doi pubmed - Boland BS, Dulai PS, Chang M, Sandborn WJ, Levesque BG. Pseudomonas meningitis during vedolizumab therapy for Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(11):1631-1632.

doi pubmed pmc - Kubota T, Mori Y, Yamada G, Cammack I, Shinohara T, Matsuzaka S, Hoshi T. Listeria monocytogenes ankle osteomyelitis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis on adalimumab: a report and literature review of listeria monocytogenes osteomyelitis. Intern Med. 2021;60(19):3171-3176.

doi pubmed pmc - Kelesidis T, Salhotra A, Fleisher J, Uslan DZ. Listeria endocarditis in a patient with psoriatic arthritis on infliximab: are biologic agents as treatment for inflammatory arthritis increasing the incidence of Listeria infections? J Infect. 2010;60(5):386-396.

doi pubmed pmc - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Listeria (Listeriosis). 2015. [online] Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/outbreaks/ice-cream-03-15/signs-symptoms.html. Accessed September 28, 2022.

- World Health Organization. Listeriosis. 2018. [online] Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/listeriosis. Accessed September 28, 2022.

- Direct healthcare professional communication Infliximab (Remicade, Flixabi, Inflectra, Remsima and Zessly): Use of live vaccines in infants exposed in utero or during breastfeeding [Internet]. Cited September 29, 2022. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/dhpc/direct-healthcare-professional-communication-dhpc-infliximab-remicade-flixabi-inflectra-remsima_en.pdf.

- Using ENTYVIO for patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease [Internet]. Cited September 29, 2022. Available from: https://www.hpra.ie/docs/default-source/3rd-party-documents/educational-materials/entyvio_hcp_physician-brochure_v1-07-15.pdf?sfvrsn=2.

- European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation. Acute severe colitis [Internet]. United Kingdom: Harbord et al. 2013-14.

- Extensive colitis [Internet]. Cited September 29, 2022. Available from: http://www.e-guide.ecco-ibd.eu/algorithm/extensive-colitis.

- Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, Hendy PA, Smith PJ, Limdi JK, Hayee B, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019;68(Suppl 3):s1-s106.

doi pubmed pmc - Hindryckx P, Novak G, Vande Casteele N, Laukens D, Parker C, Shackelton LM, Narula N, et al. Review article: dose optimisation of infliximab for acute severe ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(5):617-630.

doi pubmed pmc

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.