| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 15, Number 7, July 2024, pages 136-142

Long Duration Pembrolizumab for Metastatic Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Soft Tissue Sarcoma With Multimodality Therapy

Daniel Y. Reuben

Division of Hematology/Oncology, Hollings Cancer Center, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC 29425, USA

Manuscript submitted May 1, 2024, accepted June 8, 2024, published online June 19, 2024

Short title: Long Duration Pembrolizumab for UPS

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc4237

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Patients with undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) of soft tissue have responsiveness to immunotherapy treatment. Since few patients with soft tissue sarcoma respond to immunotherapy, guidelines for its management are lacking. Specifically, the optimal duration of immunotherapy is unclear. This report is unique owing to the probable longest reporting of successful continuous immunotherapy for metastatic UPS over 6.5 years and 109 cycles. Here a patient who developed metastatic UPS is presented. The patient required systemic therapy for metastatic sarcoma, eventually with immunotherapy. A prolonged treatment over many years is elaborated. A robust response was seen but occasionally augmented by adding external beam radiation therapy (XRT). Treatment was tolerated without adverse effects. A brief review of current treatment practice and known risks of prolonged immunotherapy is presented. For similar patients, a lengthy treatment course, beyond that utilized for other malignancies, can be considered. This is likely to be safe if it is tolerated and without early adverse effects. Other treatment modalities such as palliative surgery and XRT are described which may also be required for management of mixed responses.

Keywords: Pleomorphic; Sarcoma; Immunotherapy; Duration; Long

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The management of metastatic soft tissue sarcoma has required consideration of multiple modalities of treatment including palliative surgery, external beam radiation therapy (XRT) and systemic agents. With regards to the latter, systemic chemotherapy has been a historic mainstay. These predominately include anthracyclines, alkylating agents, topoisomerase inhibitors and anti-metabolites. Traditional side effects of fatigue, alopecia, myelosuppression and cardiotoxic risks can be experienced. Quality of life and performance status can be impaired, especially with prolonged treatment. Low response rates and incomplete responses to standard chemotherapy are common, and this begs for the development of improved agents [1].

Recently immunotherapy has been shown to provide responses in soft tissue sarcoma. As now known the side effect profile is much improved over chemotherapy. Risks involve inflammatory reactions principally, if at all. Beyond initial and scattered reports of immunotherapy responses for sarcoma patients, this use was better evaluated through enrollment of many sarcoma types in the SARC028 trial [2]. Here, cohorts of 10 patients, each representing selected sarcoma types, were enrolled with the goal to assess likelihood of response. While immunotherapy is an encouraging advancement, only certain sarcoma subtypes appear to respond [3]. The reasons for this are not yet understood. Once selected and shown effective for a patient, the duration of immunotherapy treatment and the implications of chronic treatment are clouded. No guidelines yet support or refute chronic, long-term immunotherapy for sarcoma management. Initial immunotherapy investigation for sarcoma did not report long-term outcomes or assess for extended treatment durations.

For many cancers when immunotherapy is applicable, treatment is often suspended at 2 years or when a complete response (CR) is attained. With sarcoma management, achieving a CR is less common, and when seen, it usually exceeds beyond a 2-year timepoint. Lengthy or prolonged immunotherapy could thus be a consideration when efficacy continues to be seen over many years. Herein a case is described with prolonged treatment and substantial continued response and tolerability to pembrolizumab immunotherapy for a patient with undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS). Treatment greatly exceeded 2 years given a continuous response to most metastatic sites and a favorable tolerability without new or compounding side effects. Multidisciplinary care with palliative surgery and XRT occurred for occasional, non-responding metastases. With these techniques, continued immunotherapy was possible, without the risk of changing systemic treatment to an ineffective agent. This rationale provided a continued response to the bulk of the metastatic disease for many years and maintained excellent quality of life and satisfaction for the patient.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

The patient presented in 2016 at age 57 with the development of a painful right thigh mass. His past medical history included Parkinson’s disease, hypothyroidism and hypertension. He previously underwent implantation of a neural stimulator to aid Parkinson’s symptoms. He had no other prior surgeries. He never smoked and did not drink alcohol. He had no relevant family history. He worked as a firearms and law enforcement instructor. His primary physician ordered computed tomography (CT) imaging which appeared to show a 22 × 9.8 × 8.8 cm (craniocaudal by anterior-posterior by transverse dimension) soft tissue mass at the anterior right thigh. No osseous invasion was noted (Fig. 1). A staging CT of the chest was then performed. At least seven lung nodules were noted. The largest was found to be a 1.6-cm subpleural right lower lobe lung nodule. There was a second 1.4-cm subpleural right lower lobe nodule and a 5-mm left lower lobe nodule as well. These were consistent with metastatic disease. He was evaluated by orthopedics, medical oncology and radiation oncology specialties.

Click for large image | Figure 1. CT axial imaging of the right thigh at the time of initial presentation demonstrates a heterogeneously enhancing mass deep to vastus musculature (arrowheads). This circumferentially surrounds the anterior femur with cortical scalloping and irregularity at anterior aspect. The common femoral artery and vein, superficial femoral artery and vein and sciatic nerve, are all free of tumor (all boundaries are not fully delineated in this single slice). CT: computed tomography. |

Diagnosis

For diagnostic and staging purposes, he underwent an interventional radiology procedure in January 2017 with image-guided biopsies of the mass within the right thigh and lung. At pathology review, high-grade UPS of the thigh and metastatic high-grade UPS to the lung were confirmed. The diagnosis was supported by the pleomorphic cellular histology by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining along with an immunohistochemical profile noting absent cytokeratin AE1/3, S100 and smooth muscle actin (SMA) staining. Specific protein expression or gene mutations are not yet known with this disease and thus were not germane to formulating the diagnosis. A multidisciplinary sarcoma tumor board reviewed the patient’s case. It was recommended that systemic therapy be utilized in lieu of initial surgery given the multiple lung metastases seen. XRT was not immediately recommended on account of the number and distribution of metastatic disease. A palliative resection by orthopedics, possibly after three cycles of chemotherapy, would be considered pending the response to systemic therapy.

Treatment

Anthracycline and ifosfamide (AIM) chemotherapy is often considered as an initial maneuver, but here it was felt too toxic for the patient on account of his initial performance status. The treatment with anthracycline and olaratumab, an anti-platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)α inhibitor was then elected, due to its recent approval in the USA as the first-line therapy that year and its published high response rates [4]. The patient thus commenced doxorubicin and olaratumab in February 2017.

The patient’s clinical course was followed along with radiographic restaging. After 3 months of therapy no appreciable change was noticed on the clinical exam. A CT of the right femur showed progression with enlargement of the sarcoma, now measuring 25.0 × 12.9 × 10.8 cm. In consultation with orthopedics, a palliative resection was undertaken at this time with concern that future growth could inhibit limb salvage surgery. At pathology review, grade 3 UPS was found consistent with earlier biopsies. Gross measurements were 29.5 cm in length with abutment of the bone at the deep margin. Only close, < 1 mm margins at the vastus medialis and vastus intermedius were attained. No lymphovascular invasion was present. Microsatellite testing for MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 showed intact protein expression. The patient’s postoperative course was complicated by a fall and wound dehiscence requiring reclosure 6 weeks later. With pre-existing Parkinson’s disease and recent physical debilitation, the patient had difficulty quickly regaining full weight bearing without assistance. With eventual recovery he was able to undertake new systemic therapy 3 months later.

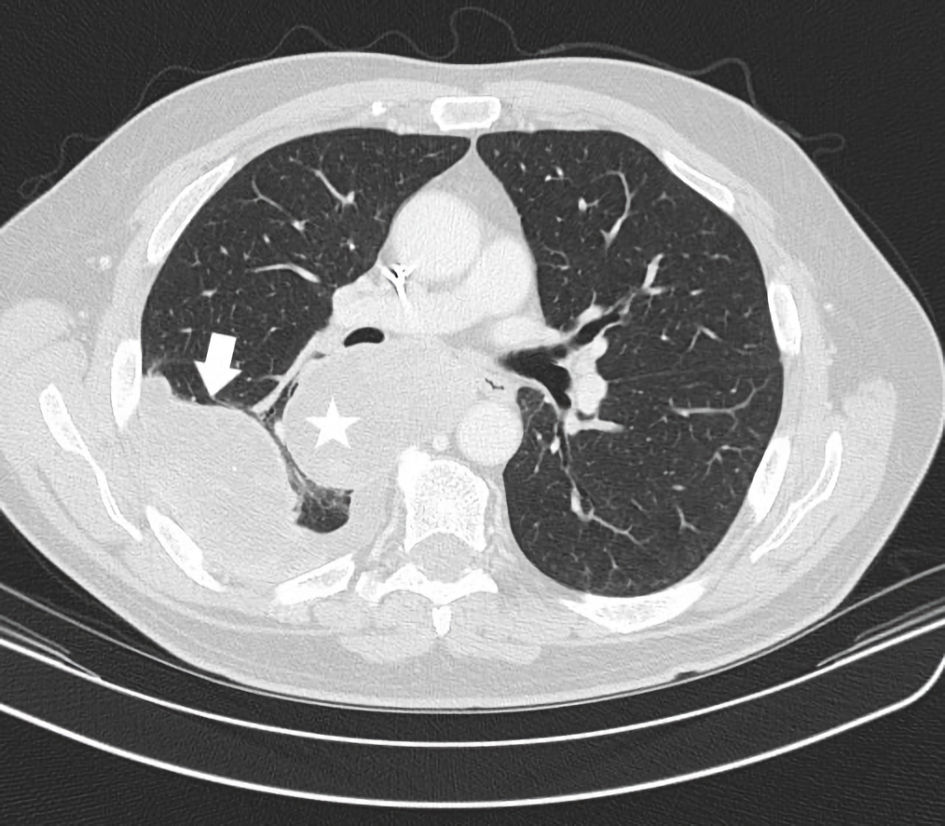

Second-line gemcitabine and docetaxel were administered in August 2017 as often considered in this position for most soft tissue sarcomas including UPS. However, by the next immediate restaging, further progression with sizeable growth of pulmonary metastases was seen. In particular a right perihilar mass of 7.4 cm developed. There was also an increased left lower lobe mass of 3 cm and a right lower lobe subpleural mass measuring 7.4 cm (Fig. 2). Third-line therapy was then considered. Based on the recent results of the SARC028 trial, immunotherapy with pembrolizumab 200 mg intravenous (IV) every 3 weeks was undertaken in October 2017. Prior to this timepoint, only sporadic case reports or small series were available with most showing no immunotherapy responsiveness with this disease. This trial demonstrated robust responses with many sarcoma patients. The chance of a response was higher for UPS patients than prior chemotherapeutic options. Beyond responses, the side-effect profile of immunotherapy with sarcoma patients was also beneficial; traditional chemotherapy side effects were not seen. These points formulated an attractive option for the patient and clinician to select this strategy.

Click for large image | Figure 2. CT axial imaging of chest just prior to instituting immunotherapy shows the status of prominent pulmonary metastases. A right perihilar mass posterior to the right mainstem bronchus (star) and a separate right lower lobe pleural based mass with small effusion (arrow) are depicted. CT: computed tomography. |

Follow-up and outcomes

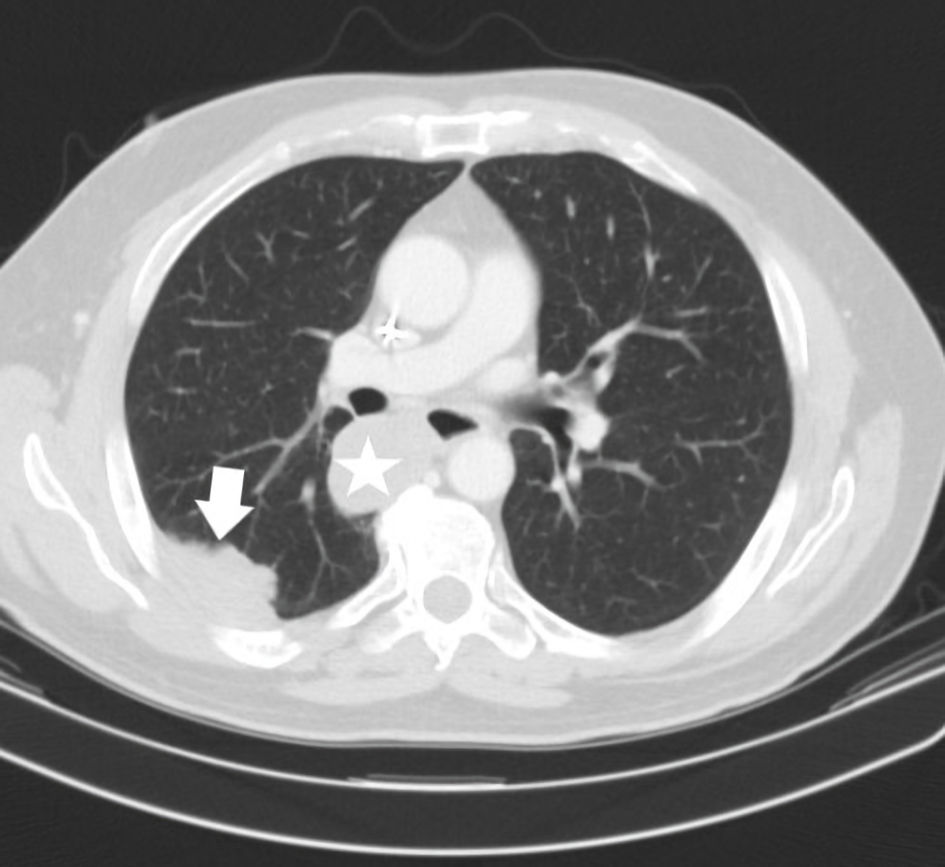

In utilizing pembrolizumab, the metastatic UPS began to respond immediately. Restaging CT imaging showed a dramatic 40% reduction in metastases by the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumor (RECIST) measurements 3 months later (Fig. 3). The patient tolerated immunotherapy well. Treatment was complicated by grade 1 pruritis. This occurred in absence of a rash and was managed with topical emollients. With pre-existing hypothyroidism, occasional adjustment of Synthroid was also needed on the basis of biochemical changes in thyroid hormone levels. He was asymptomatic to fluctuations of this endocrinopathy. Overall, immunotherapy allowed the patient to retain an exceptional quality of life.

Click for large image | Figure 3. CT axial imaging of chest (January 2018) was performed as initial restaging to assess an early immunotherapy response. This demonstrates a substantially reduced size of the right perihilar mass now measuring 4.5 cm, previously 7.4 cm (star). The right lower lobe pleural mass has reduced to 5.2 cm, previously 7.4 cm (arrow). CT: computed tomography. |

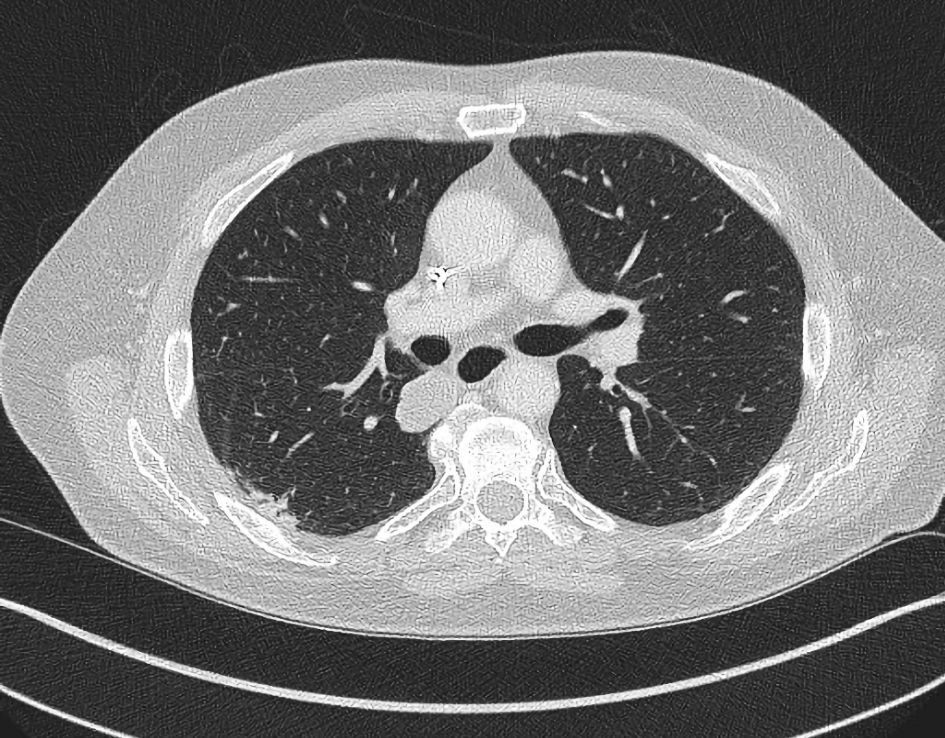

Through 2018, continued response of pulmonary metastases was ongoing. At this time a newly recurrent disease within the right thigh was suspected based on radiographic imaging. This was confirmed on biopsy. He was again evaluated by radiation oncology and ultimately received XRT to 3,900 cGy directed to the surgical bed of the right thigh. Immunotherapy was continued. Further diminished size of pulmonary metastatic disease continued to be demonstrated (Fig. 4). No recurrent growth in the thigh was ever later found. With successive follow-up appointments, the patient continued to tolerate treatment without new side effects. Restaging and clinical exam evaluations showed continued response to immunotherapy. A singular point of remission was not seen, but rather a continuous and ongoing improvement in most metastases was witnessed. With this ongoing result the patient did not want to take a treatment holiday. Both patient and clinician aimed to find the best remission or stable disease state and continued treatment on schedule.

Click for large image | Figure 4. CT axial imaging of chest (October 2019) after the patient received immunotherapy for 2 years, demonstrates resolution of the right lower lobe pleural/subpleural mass (compare with Figure 3) and a decreased right perihilar mass measuring 3 cm (not depicted in same image due to different axial slice). CT: computed tomography. |

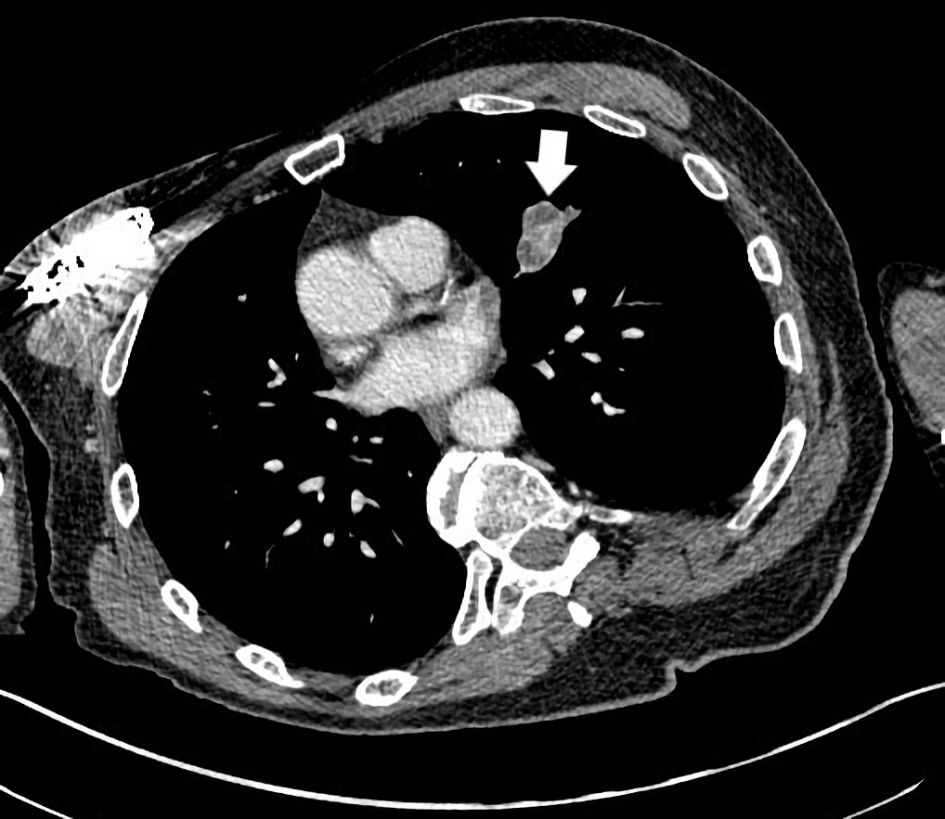

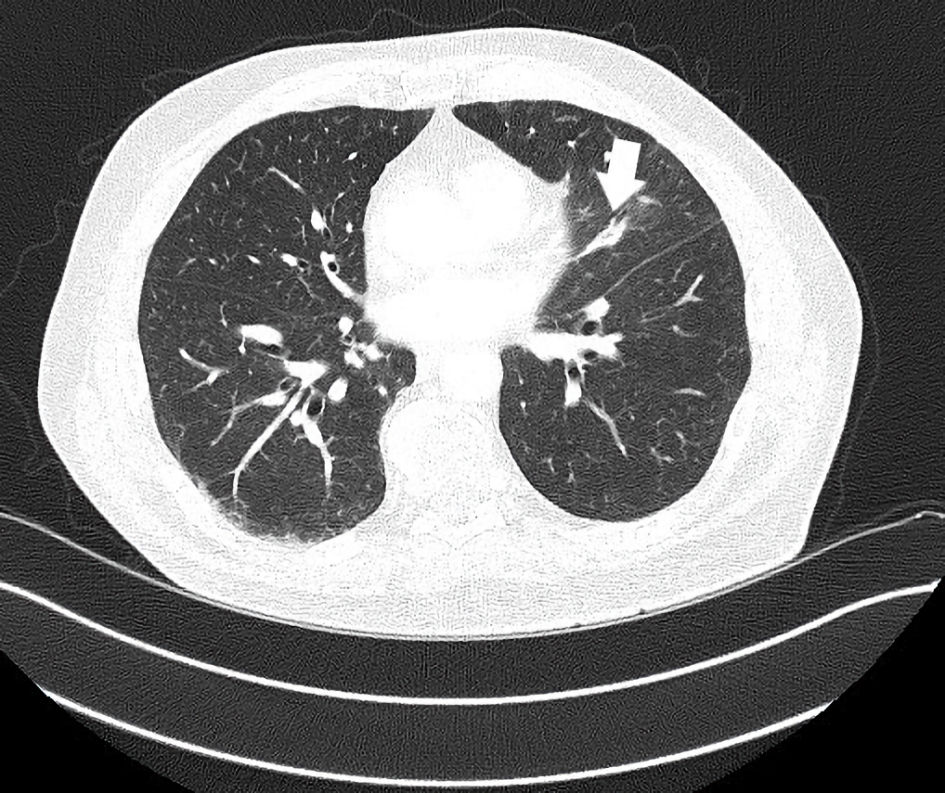

In January 2022, nearly 5 years from his initial treatment start, a re-referral to radiation oncology was again undertaken. At this time a small heft upper lobe pulmonary metastasis ceased responding and grew, yielding a mixed response. The mass then measured 3.4 cm in largest dimension (Fig. 5). He underwent XRT (50 Gy in five fractions) and again continued immunotherapy. A substantial shrinkage of the metastasis to 1.4 cm was seen 3 months later (Fig. 6). Beyond this time, complete disappearance of the metastasis was attained by February 2023. The patient’s other (non-irradiated) metastatic lung lesions continued to respond to chronic immunotherapy albeit slowly. During follow-up visits, a number of discussions with the patient regarding the benefits and risks of continued treatment versus a holiday were reviewed. The patient insisted on continued treatment given ongoing further improvements with restaging studies. He judged he might jeopardize ongoing disease control efforts if he paused treatment. He has now undertaken 109 cycles of pembrolizumab by May 2024, for 6.5 years. Other than the previously noted minor side effects, no new ones have been experienced. His quality of life has remained favorable compared to other patients with metastatic sarcoma requiring prolonged chemotherapy. On follow-up, the patient mentioned numerous times that he was extremely satisfied with treatment despite the frequent visits and testing required. He recalled his energy was improved over that experienced with chemotherapy. He believed his survival trajectory was improved with electing immunotherapy especially given earlier failures with traditional chemotherapy. He frequently noted participation in activities that interest him along with family gatherings he could attend without impaired performance status from the treatment. He continued law-enforcement consulting work and charitable events as well. To date the remaining small volume metastatic lung disease remains stable and no local re-recurrence in the leg has been found.

Click for large image | Figure 5. CT axial imaging of the chest indicates a left upper lobe mass measuring 3.4 ×2.5 cm (arrow) which became unresponsive to immunotherapy and progressed. CT: computed tomography. |

Click for large image | Figure 6. CT axial imaging of the chest 2 months post-irradiation with continued immunotherapy shows improved size of left upper lobe mass now 1.4 × 0.8 cm (arrow). This lesion disappeared with successive restaging by the following year with ongoing immunotherapy. CT: computed tomography. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

A prolonged use of immunotherapy for the treatment of metastatic UPS is presented. There is little guidance about the next steps. For example, it is not clear as to when treatment should be stopped. It is also not yet known if treatment holidays alternating with treatment resumption is more or less favorable. Furthermore, if treatment is continued for many years, there could be a risk that long-term side effects outweigh perceived safety and efficacy. These points are worth considering.

The paradigm of how to direct immunotherapy use, including its duration, has followed from its development for patients with melanoma [5]. For metastatic melanoma management, the custom has been to utilize immunotherapy for up to a 2-year course and then suspend if a CR or good partial response (PR) is seen, as per early experiences [6, 7]. Later clinical trials of pembrolizumab for other diseases have also used a 2-year treatment period [8-10]. Recently this was a trial construct for assessing pembrolizumab with sarcoma patients as well [11]. For some cancers a CR is not easily attained, so reaching a satisfactory stopping point may not occur. It is not clear that limiting immunotherapy to 2 years in such a case would be justified. Also germane to this patient case was a mixed or “dissociative” response short of CR. In this scenario the use of prolonged immunotherapy can be supported [12], especially if adjunctive modalities of treatment (e.g., surgery or XRT) can be used. To date, guidance is not forthcoming from trials to answer questions regarding total duration of immunotherapy for similar sarcoma patients. Further data such as shown herein will be useful to consider.

A two-fold concern for prolonged immunotherapy is the continued risk of side effects and concern for diminished long-term response if resistance develops. Regarding the first point, side effects appear to present randomly with respect to time from initial treatment start. Still overall this is often early, within the first year. Side effects might extend to the 123rd week in one report [13]. The appearance of fatal side effects also appears early and was not seen beyond 585 days in a large meta-analysis investigating 31,059 reactions [14]. These reports potentially present some confidence in the safety of prolonged immunotherapy so long as no significant adverse effects occur within the first 2 years or so.

If chronic immunotherapy is given, a concern arises that it may induce resistance. As acquired resistance in the context of immunotherapy is not fully understood, consideration of how to identify this and reduce its occurrence is important. A few hypotheses suggest it is due to alterations in gene expression, epigenetic changes of protein structure, changes in the major

histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecule required for an immune response, alteration in cell signaling which may affect paracrine signals such as interferon-γ release, gene deletions, or changes in local T-cell subsets among others. Unfortunately, further work is needed before a recommendation of how to detect resistance and intervene can be made [15].

Breaks from immunotherapy could represent a way resistance might be forestalled. Currently there is little data available regarding chronic versus intermittent or metronomic immunotherapy approaches. A concern with any treatment delay is loss of efficacy. With anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA4) immunotherapy, a delay over 2 months could still yield a response [16]. This is not clearly described with pembrolizumab (anti-programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1)) use. Thus, a trial which would interrupt ongoing immunotherapy amidst active metastatic disease could be designed yet possibly difficult to accrue to. Potentially this will be a subject of future study.

It is not uncommon to find a mixed response on restaging with metastatic soft tissue sarcoma patients undertaking chronic therapy. As shown here, specific metastatic deposits may lose responsiveness. By harnessing ablation such as with radiation therapy, systemic therapy can still be continued successfully while gaining local control of a particular metastasis. This has been noted previously [17, 18]. In a large study the local control rate of doing so with sarcoma patients was high and a 2-year local failure rate was 7.4% [19]. With specific consideration of using immunotherapy and radiation these can be undertaken simultaneously with good effect. A high PR and CR rate may be seen with possible abscopal effect as well [20]. All of these points constitute a strong rationale to not change systemic therapy with metastatic sarcoma patients unless significant widespread or repetitive disease progression occurs.

Treatment decisions pertaining to soft tissue sarcoma management are complex and not easily summarized in a short review. Due to scores of histologic subtypes and a prolific variability of where metastases occur, a patient-centric approach is paramount. Guidelines cannot fully encompass all possible treatment choices. Regarding metastatic UPS even NCCN, guidelines do not specify treatment for this subtype. The recommendation for pembrolizumab, if it is to be employed at all, is referenced to the noted SARC028 trial which was a preliminary investigation to assess immunotherapy response in multiple histologies [21]. A treatment algorithm for UPS management is elusive. Additionally frustrating is that biomarkers such as PD-L1 expression is not tied to immunotherapy response in UPS or other sarcomas [22, 23]. Regardless, in reviewing the high likelihood of UPS responding to immunotherapy, strong consideration should be made to utilizing this early in a successive line of considered treatment options. For this patient it was noted that he had intact microsatellite genes, and his response therefore is germane to the UPS histology. It is also shown that despite two separate lung metastases which lost an immune response, others continued to respond and did so for many years after immunotherapy was started. This suggests a patient can benefit from prolonged immunotherapy beyond an arbitrary 2-year course as undertaken for other malignancies.

The consideration of prolonged immunotherapy is a concept for future researchers to consider based upon patient experiences such as this one. Given that a safe chronic treatment was provided, then investigating a larger number of patients within the construction of a new clinical trial would be worthwhile. A trial could be designed without a customary cap of 2 years of immunotherapy, at least for patients who demonstrate ongoing responses to most of their metastatic disease. Similarly, a trial could also incorporate multi-modality therapy such as XRT if at most < 20% progression by RECIST is seen.

Currently, prolonged therapy is a concern regarding resource management. Given the financial costs of immunotherapy agents, the associated costs of laboratory testing and clinical visits, a large financial bill is generated with ongoing immunotherapy use. Other issues such as procurement of needed quantities of drug, infusion chair availability and clinic throughput can be affected by scores of patients exposed to increased therapy durations. While a physician’s viewpoint may be to advocate for improved survival times by delivering longer durations of treatment, this becomes counterweighted by these other points as well. How this will be rectified will perhaps rely on local governance of health systems, insurance plans, government and resource allotment. Hopefully shared solicitation of patient and physician experience will be taken into consideration to assist future guideline development.

In summary, the rationale for choosing immunotherapy in this case was to leverage a histology-specific treatment judged to have a high chance of success with a backdrop of ongoing disease progression using chemotherapy. The impaired performance status of the patient was also a prominent factor in selecting immunotherapy. Considering the patient did not benefit from two lines of chemotherapy-based treatment, a personalized prediction of response to next agents would be ideal. However metastatic sarcoma management has been undertaken respecting historic trial results and rarely on the basis of genetics or biomarkers since, to date, these have been elusive compared with other cancers [1]. The patient and clinician selected immunotherapy given the reported high rates of responsiveness seen with UPS patients. As the patient’s current immunotherapy commenced at the time of the SARC028 publication, it is likely he has one of the longest described continuous treatments with pembrolizumab for soft tissue sarcoma management. It is noted that the described, adjunctive strategies of debulking surgery and radiation play a role in sarcoma management even if metastatic disease is seen. This concept can allow for continued systemic therapy to continue.

Learning points

Patients with soft tissue sarcoma have multiple treatment options but most responses to chemotherapy are short lived. On the basis of recent studies, patients with UPS sarcoma have a reasonable likelihood of response to immunotherapy. As immunotherapy responses can continue over many years, a stopping point is important to consider. The risk of adverse reactions appears low with long-term use of immunotherapy. Nevertheless, understanding acquired resistance and methods to circumvent are also important objectives. As shown non-responding metastases can be successfully treated with radiation in conjunction with immunotherapy. Hopefully further research will soon elaborate guidelines for total duration of immunotherapy for UPS patients. Until then an individualized treatment approach is necessary. This report will hopefully assist in developing a body of evidence pertaining to outcomes of prolonged immunotherapy use for sarcoma patients.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

No funding was requested for this work.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that there is no potential conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying figures.

Author Contributions

The author listed is the sole author of this manuscript with involvement in conceptualization, writing, review and editing.

Data Availability

The deidentified data involved with this case report can be made available with appropriate request.

Abbreviations

UPS: undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma; CR: complete response; PR: partial response; XRT: external beam radiation therapy

| References | ▴Top |

- Gamboa AC, Gronchi A, Cardona K. Soft-tissue sarcoma in adults: An update on the current state of histiotype-specific management in an era of personalized medicine. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(3):200-229.

doi pubmed - Tawbi HA, Burgess M, Bolejack V, Van Tine BA, Schuetze SM, Hu J, D'Angelo S, et al. Pembrolizumab in advanced soft-tissue sarcoma and bone sarcoma (SARC028): a multicentre, two-cohort, single-arm, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(11):1493-1501.

doi pubmed pmc - Baldi GG, Gronchi A, Tazzari M, Stacchiotti S. Immunotherapy in soft tissue sarcoma: current evidence and future perspectives in a variegated family of different tumor. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2022;22(5):491-503.

doi pubmed - Tap WD, Jones RL, Van Tine BA, Chmielowski B, Elias AD, Adkins D, Agulnik M, et al. Olaratumab and doxorubicin versus doxorubicin alone for treatment of soft-tissue sarcoma: an open-label phase 1b and randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10043):488-497.

doi pubmed pmc - Phan GQ, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Hwu P, Topalian SL, Schwartzentruber DJ, Restifo NP, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity induced by cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(14):8372-8377.

doi pubmed pmc - Topalian SL, Sznol M, McDermott DF, Kluger HM, Carvajal RD, Sharfman WH, Brahmer JR, et al. Survival, durable tumor remission, and long-term safety in patients with advanced melanoma receiving nivolumab. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(10):1020-1030.

doi pubmed pmc - Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, Arance A, Grob JJ, Mortier L, Daud A, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2521-2532.

doi pubmed - Hughes BGM, Munoz-Couselo E, Mortier L, Bratland A, Gutzmer R, Roshdy O, Gonzalez Mendoza R, et al. Pembrolizumab for locally advanced and recurrent/metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-629 study): an open-label, nonrandomized, multicenter, phase II trial. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(10):1276-1285.

doi pubmed - Antonarakis ES, Piulats JM, Gross-Goupil M, Goh J, Ojamaa K, Hoimes CJ, Vaishampayan U, et al. Pembrolizumab for treatment-refractory metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: multicohort, open-label phase II KEYNOTE-199 study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(5):395-405.

doi pubmed pmc - Monk BJ, Tewari KS, Dubot C, Caceres MV, Hasegawa K, Shapira-Frommer R, Salman P, et al. Health-related quality of life with pembrolizumab or placebo plus chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer (KEYNOTE-826): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24(4):392-402.

doi pubmed - Blay JY, Chevret S, Le Cesne A, Brahmi M, Penel N, Cousin S, Bertucci F, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with rare and ultra-rare sarcomas (AcSe Pembrolizumab): analysis of a subgroup from a non-randomised, open-label, phase 2, basket trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24(8):892-902.

doi pubmed - Yin J, Song Y, Tang J, Zhang B. What is the optimal duration of immune checkpoint inhibitors in malignant tumors? Front Immunol. 2022;13:983581.

doi pubmed pmc - Tang SQ, Tang LL, Mao YP, Li WF, Chen L, Zhang Y, Guo Y, et al. The pattern of time to onset and resolution of immune-related adverse events caused by immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer: a pooled analysis of 23 clinical trials and 8,436 patients. Cancer Res Treat. 2021;53(2):339-354.

doi pubmed pmc - Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, Chandra S, Menzer C, Ye F, Zhao S, et al. Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(12):1721-1728.

doi pubmed pmc - Sharma P, Hu-Lieskovan S, Wargo JA, Ribas A. Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;168(4):707-723.

doi pubmed pmc - Kyi C, Carvajal RD, Wolchok JD, Postow MA. Ipilimumab in patients with melanoma and autoimmune disease. J Immunother Cancer. 2014;2(1):35.

doi pubmed pmc - Reuben DY. A prolonged response and characteristics of trabectedin treatment of metastatic soft tissue sarcoma. J Med Cases. 2021;12(4):160-163.

doi pubmed pmc - Asha W, Koro S, Mayo Z, Yang K, Halima A, Scott J, Scarborough J, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for sarcoma pulmonary metastases. Am J Clin Oncol. 2023;46(6):263-270.

doi pubmed - Lebow ES, Lobaugh SM, Zhang Z, Dickson MA, Rosenbaum E, D'Angelo SP, Nacev BA, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for sarcoma pulmonary metastases. Radiother Oncol. 2023;187:109824.

doi pubmed - Callaghan CM, Seyedin SN, Mohiuddin IH, Hawkes KL, Petronek MS, Anderson CM, Buatti JM, et al. The effect of concurrent stereotactic body radiation and anti-PD-1 therapy for recurrent metastatic sarcoma. Radiat Res. 2020;194(2):124-132.

doi pubmed pmc - National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Soft Tissue Sarcoma (Version 3.2023) https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/sarcoma.pdf.

- Burgess MA, Bolejack V, Van Tine BA, Schuetze S, Hu J, D’Angelo SP, Attia S, et al. Multicenter phase II study of pembrolizumab (P) in advanced soft tissue (STS) and bone sarcomas (BS): Final results of SARC028 and biomarker analyses. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(suppl):11008.

doi - Zhang Y, Chen Y, Papakonstantinou A, Tsagkozis P, Linder-Stragliotto C, Haglund F. Evaluation of PD-L1 expression in undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas, liposarcomas and chondrosarcomas. Biomolecules. 2022;12(2):292.

doi pubmed pmc

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.