| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 15, Number 10, October 2024, pages 272-277

Thrombotic Microangiopathy After Long-Lasting Treatment by Gemcitabine: Description, Evolution and Treatment of a Rare Case

Lise Bertina, Marion Gauthiera, e, Fanny Boullengera, Isabelle Brocherioub, Raphaelle Chevallierb, Florence Maryc, Robin Dhoted, Xavier Belenfanta

aNephrology Department, Hospital Andre Gregoire, Montreuil, France

bAnatomopathology Department, Assistance Publique-Hopitaux de Paris (APHP), Sorbonne University, Hospital Pitie-Salpetriere, Paris, France

cGastroenterology Department, Assistance Publique-Hopitaux de Paris (APHP), Sorbonne University, Hospital Avicenne, Bobigny, France

dInternal Medicine Department, Assistance Publique-Hopitaux de Paris (APHP), Sorbonne University, Hospital Avicenne, Bobigny, France

eCorresponding Author: Marion Gauthier, Service de Nephrologie, Hopital Andre Gregoire, Montreuil, France

Manuscript submitted May 20, 2024, accepted July 16, 2024, published online September 20, 2024

Short title: TMA After Gemcitabine Treatment

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc4253

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) is an uncommon but severe complication that may occur in cancer patients under gemcitabine chemotherapy. Gemcitabine-induced thrombotic microangiopathy (G-TMA) can clinically and biologically present as atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, with activation of the complement pathway asking the question of the use of eculizumab. We describe here the case of a patient suffering from metastatic cholangiocarcinoma treated by gemcitabine for 4 years leading to the remission of the underlying neoplasia. Despite an impressive response to therapy, she developed thrombopenia, regenerative anemia, and acute kidney injury leading to the suspicion then diagnosis based on the renal biopsy of a very late G-TMA. Spontaneous evolution after treatment interruption was favorable without dialysis requirement. However, in this case where gemcitabine is the only chemotherapy remaining for a mortal underlying condition, we discussed the re-initiation of gemcitabine under eculizumab treatment. This atypical case of TMA illustrates the importance of recognizing, even belatedly, this rare but serious complication of chemotherapy. It asks the question of rechallenging discontinued chemotherapy notably under eculizumab cover, in this population with a high risk of cancer progression.

Keywords: Thrombotic microangiopathy; Acute kidney failure; Hypertension; Gemcitabine; Eculizumab

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) is defined by hemolytic anemia, peripheral thrombopenia, and various organ injuries due to ischemia after capillary thrombosis [1]. The kidney is one of the most impacted organs with clinical presentation of oligo-anuric acute kidney failure of vascular origin.

Two main etiologies of TMA in the adulthood population are: 1) thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) presenting with prevalent neurological disorders and deficit of ADAMTS13 activity; and 2) atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) characterized by quantitative or qualitative abnormalities in regulatory proteins of the complement alternative pathway. Typical HUS due to capillary endothelium alteration by infectious mechanism is less frequent than in children. Other conditions can be associated with TMA and need to be investigated, including various infections, connective tissue disorders, malignant tumors, and drug exposure as chemotherapies. Gemcitabine is one of the usual agents implicated in secondary TMA with frequent severe renal involvement and poor prognosis [2]. The management of gemcitabine-induced TMA (G-TMA) is not codified.

We reported here a case of histologically proven TMA with isolated kidney acute failure in a woman suffering from cholangiocarcinoma under long-lasting gemcitabine chemotherapy.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

On May 2022, a 55-year-old woman was admitted to our nephrology department for suspicion of TMA.

Patient’s medical history included intracerebral hemorrhage due to aneurysmal rupture in 2011 complicated by chronic epilepsy, type two diabetes mellitus under insulin therapy with chronic kidney disease stage 3A (glomerular filtration rate (GFR) = 44 mL/min/1.73 m2), hypertension, and chronic psychosis. She developed a cholangiocarcinoma (histologically proven) with liver and lymph node metastasis in 2018 and was put under chemotherapy including gemcitabine and platinum salt agent (GEMOX) all 21 days until March 2022 then gemcitabine alone. At the moment of hospitalization, she had 37 cures of gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2 (cumulated dose of 37 g/m2).

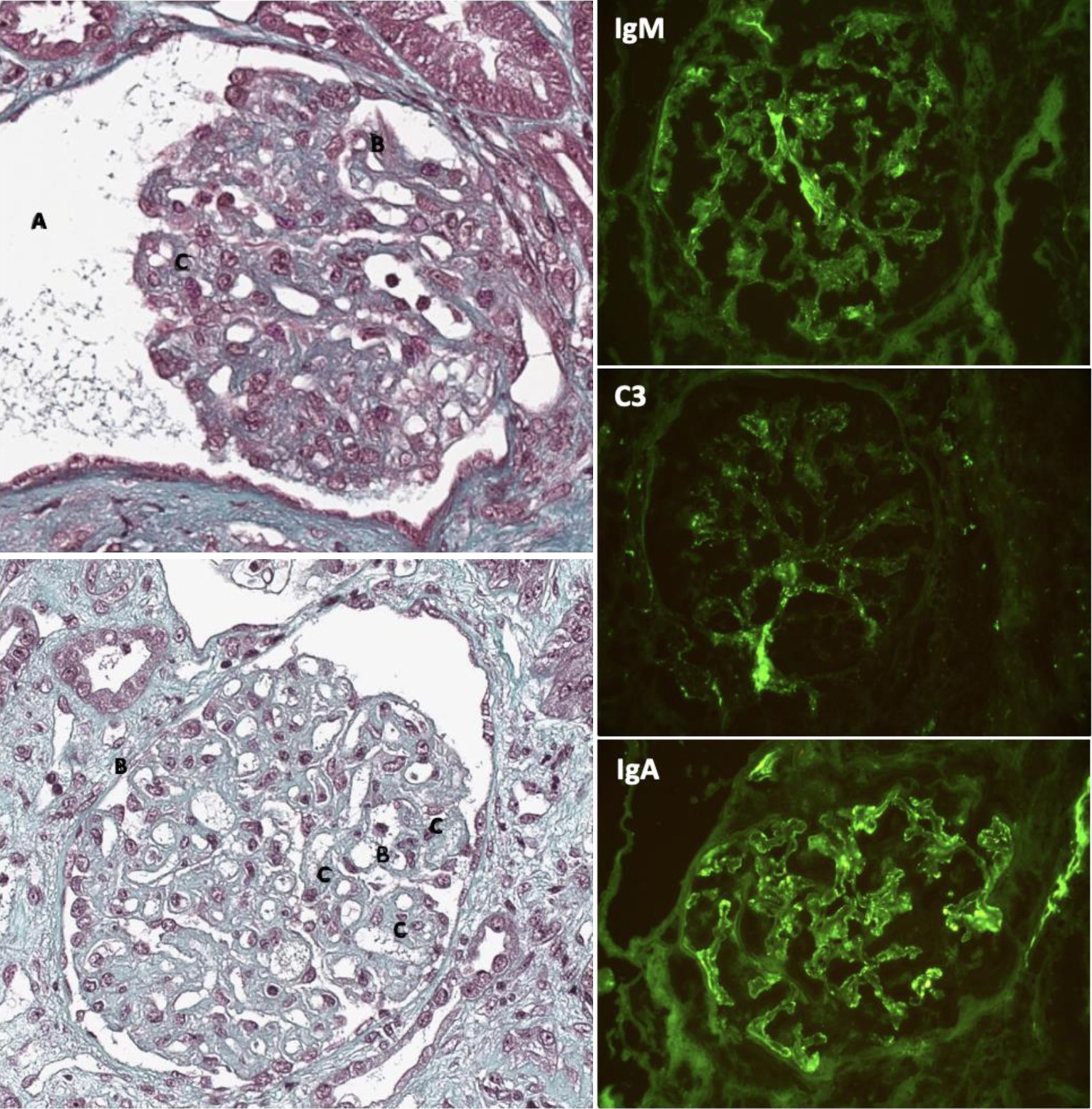

She consulted for global fatigue in April 2022. At the entrance, the clinical examination revealed general psychomotor slowing, and no other clinical sign was noted. She had normal blood oxygenation, apyrexia, and high blood pressure at 200/80 mm Hg. Standard biology revealed regenerative anemia (hemoglobinemia 7.3 g/dL and reticulocytes 115,000/mm3) with schistocytes (1.5%), indosable haptoglobin, thrombopenia (125,000/mm3) and organic acute kidney injury with serum creatinine level at 880 µmol/L, urea fractional excretion 54%, no glomerular range proteinuria (70 mg/mmol) and microscopic hematuria. Renal echography showed two normally cortico-medullary differentiated kidneys of 11.8 and 11.2 cm, without hydronephrosis. Renal biopsy (Fig. 1) confirmed the diagnosis with lesions of chronic TMA including double contour appearance of the glomerular basement membranes and swelling and detachment of glomerular endothelial cells associated with acute tubular necrosis. Immunofluorescence (IF) staining for complement factors (C3+, IgM+++, and IgA+++) was also seen (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Renal biopsies in TMA due to gemcitabine. (Left column) Immunohistochemistry with Masson trichrome showing (A) ischemic glomerulus with flocculus retraction, (B) doubling of glomerular basement membrane, (C) glomerular mesangiolysis. (Right column) Immunofluorescence showing positive staining for IgM, C3, and IgA. |

In front of TMA with neurological impairment, TTP was first excluded with ADAMTS13 level of 121% and cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed no posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). HUS was then investigated; the patient did not report any episode of diarrhea, fever, and urinary symptoms. Hemocultures were sterile, cytobacteriological examination of urines (CBEU) did not show leukocytosis or bacteria, and no Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) analysis could be performed (no stool culture). Complement biological investigation (C3, C4, CH50, protein I, protein H, MCP, factor-H antibody negative) was normal; no genetic analysis was performed (on expert opinion).

Other causes of secondary TMA were ruled out: plasmatic B-human chorionic gonadotropin was negative, no autoimmunity was found (no antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), neither lupus anticoagulant, B2GP1 antibody nor anticardiolipin antibody), and hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus serologies were negative. Neoplastic causes were excluded after a thoracic-abdominal-pelvic computed tomography scan and liver MRI showed remission of cholangiocarcinoma and no sign of new tumoral disease.

We finally considered exclusion of an iatrogenic cause of TMA due to gemcitabine. The evolution was spontaneously favorable with progressive amelioration of serum creatinine level without dialysis necessity. However, a chronic kidney disease persists, with the last creatinine level of 22 mg/L and GFR of 28 mL/min/1.73 m2.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

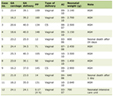

TMA following the course of neoplasia could be differentiated into paraneoplastic TMA and drug-induced TMA (15% of acute kidney injury in cancer) [2]. Iatrogenic TMA includes TMA under anti-vascular epithelial growth factor (VEGF) and TMA post-chemotherapy. Two major chemotherapies are concerned: mitomycin C and gemcitabine (reported incidence: 0.015-2.2% [3]), both dose-depending. Regarding the median time for the development of G-TMA, the largest retrospective study of 120 cases reported by Daviet et al found a median time of 7 months (4 - 8.5) [4], close to 7.5 months (2 - 34) from the other largest retrospective study (29 cases) reported by Glezerman et al [5]. Surprisingly, in our case, G-TMA develops after a very long exposure to gemcitabine (i.e., 58 months). Even after an extensive search in the literature and in the largest cohorts of G-TMA (reported in Table 1 [3-21]), we did not find any cases that late. Our work therefore highlights the need to remain vigilant under gemcitabine treatment and to suspect the occurrence of G-TMA in the event of biological abnormalities, even in patients who have been treated for a very long time. However, the cumulative dose of gemcitabine received by our patient (37 g/m2) could be more important than the total duration of treatment, close to the median cumulative dose of 22 g/m2 (4 - 81) reported by Glezerman et al and 21 (2.8 - 53.6) in the study of Takigawa et al [6].

Click to view | Table 1. Cumulative Dose and Median Duration of Gemcitabine Treatment at Time of Thrombotic Microangiopathy Development, Review of the Literature |

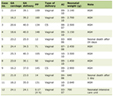

Although 56% of cases can biologically resolve after gemcitabine discontinuation [7], G-TMA prognostic can be severe with 25% of cases presenting with chronic renal insufficiency and high mortality at 4 months (60%) [2] principally due to neoplastic progression after chemotherapy discontinuation. Until a recent study by Grall et al in 2021 [8], the treatment of G-TMA has not been well codified apart from permanent discontinuation of gemcitabine and supportive cares. Plasma exchanges and corticosteroids are generally tried with poor efficacy reported at the contrary of TTP. Although underlying pathophysiological mechanisms involved are not known and no complement alternative pathway-related abnormalities have been described in G-TMA [8, 9, 22], clinical presentation and normal ADAMTS 13 level are reminiscent of aHUS. This is supported by the presence of complement factors on IF staining in 32/33 (97%) cases with G-TMA who underwent renal biopsy and IF staining in the literature (Table 2 [8, 11, 23-24]), including our case. In particular, the largest study by Grall et al [8] reported 29 patients all with G-TMA who showed C5b9 (membrane attack complex) deposits along the glomerular and tubular membrane and in the capillary wall. In this context, eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody directed against complement protein C5 used in aHUS, has been used and seemed efficient in numerous case reports of G-TMA [7, 10-16, 25]. The observational retrospective study of Grall et al [8] reported 12 cases of G-TMA treated by eculizumab after gemcitabine discontinuation with a median of four injections and 900 mg/injection. Eighty-three percent of patients had a hematological response and 84% achieved a complete (17%) or partial (67%) renal response without exacerbation or relapse after eculizumab discontinuation. The spontaneous recovery of our patient after gemcitabine discontinuation did not indicate the treatment of eculizumab in the active phase of G-TMA. However, the continuation of treatment of metastatic cholangiocarcinoma in recovery under gemcitabine appears to be a vital question. In reported cases, discontinuation of chemotherapy in the acute phase of G-TMA is noted as important as specific G-TMA treatment [8, 9, 22]. However, the survival rate also depends on underlying disease with 5/6 deaths during follow-up due to the progression of the underlying disease in the series of Grall et al [8]. The number of cases of gemcitabine re-challenge is few [5, 16-18] and with variable outcomes (stability, second TMA episode, underlying disease progression). After a multidisciplinary meeting of experts on our patient’s file, it has been decided that if gemcitabine is the only possibility and needs to be performed to maintain recovery, it could be done under maintenance treatment with eculizumab 1,200 mg every 2 weeks. Although our patient has not yet benefited from it, we would like to highlight that the possibility of re-challenge gemcitabine under treatment with eculizumab has not been studied so far, apart from a case reported by Efe et al [26]. In this latter case, even if no recurrence of TMA occurred under eculizumab 900 mg IV per week, the study is limited by the patient’s death due to cholangiocarcinoma progression only 4 weeks after re-challenge of gemcitabine. In this context, we think that larger studies on extended exposure time to gemcitabine and eculizumab should be performed addressing the question of whether or not gemcitabine and eculizumab can both be used safely after G-TMA.

Click to view | Table 2. Summary of Immunofluorescence Staining of Complement in Renal Biopsy of G-TMA |

In an extended view, assessment of gemcitabine re-challenge under rituximab therapy could also be investigated, as it is another treatment improving the course of G-TMA in several case reports probably by the decrease of B cells and autoantibodies [19, 23, 27, 28].

Conclusion

Here, we report an atypical case of TMA after a very long treatment of gemcitabine in a patient suffering from metastatic cholangiocarcinoma with favorable spontaneous evolution after discontinuation of gemcitabine. The question of whether or not eculizumab’s addition to gemcitabine treatment can be used after a first TMA episode in this population at risk of cancer progression and mortality without other possible chemotherapy needs to be addressed in larger studies.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

The authors have no perceived fund for this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Author Contributions

Lise Bertin wrote the manuscript text. Marion Gauthier corrected the manuscript and managed the patient. Fanny Boullenger, Isabelle Brocheriou and Raphaelle Chevallier performed the histological examination and interpretation of kidney biopsies. Florence Mary provided informations about oncologic past and treatment of the patient. Robin Dhote and Xavier Belenfant were major contributors in diagnosing and managing the patient. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

aHUS: atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome; ANA: antinuclear antibodies; CBEU: cytobacteriological examination of urines; G-TMA: thrombotic microangiopathy under gemcitabine; HUS: hemolytic uremic syndrome; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PRES: posterior-reversible encephalopathy syndrome; STEC: Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli; TMA: thrombotic microangiopathy; TTP: thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura; VEGF: vascular epithelial growth factor

| References | ▴Top |

- Coppo P, Veyradier A. Microangiopathies thrombotiques: physiopathologie, diagnostic et traitement. Reanimation. 2005;14(7):594-603.

- Kheder El-Fekih R, Deltombe C, Izzedine H. [Thrombotic microangiopathy and cancer]. Nephrol Ther. 2017;13(6):439-447.

doi pubmed - Fung MC, Storniolo AM, Nguyen B, Arning M, Brookfield W, Vigil J. A review of hemolytic uremic syndrome in patients treated with gemcitabine therapy. Cancer. 1999;85(9):2023-2032.

doi pubmed - Daviet F, Rouby F, Poullin P, Moussi-Frances J, Sallee M, Burtey S, Mancini J, et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy associated with gemcitabine use: Presentation and outcome in a national French retrospective cohort. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85(2):403-412.

doi pubmed pmc - Glezerman I, Kris MG, Miller V, Seshan S, Flombaum CD. Gemcitabine nephrotoxicity and hemolytic uremic syndrome: report of 29 cases from a single institution. Clin Nephrol. 2009;71(2):130-139.

doi pubmed - Takigawa M, Tanaka H, Washiashi H, Onoda T, Ishigami A, Ishii T. Time to onset of gemcitabine-induced thrombotic microangiopathy in a Japanese population: a case series and large-scale pharmacovigilance analysis. Cancer Diagn Progn. 2023;3(1):115-123.

doi pubmed pmc - Al Ustwani O, Lohr J, Dy G, Levea C, Connolly G, Arora P, Iyer R. Eculizumab therapy for gemcitabine induced hemolytic uremic syndrome: case series and concise review. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;5(1):E30-33.

doi pubmed pmc - Grall M, Daviet F, Chiche NJ, Provot F, Presne C, Coindre JP, Pouteil-Noble C, et al. Eculizumab in gemcitabine-induced thrombotic microangiopathy: experience of the French thrombotic microangiopathies reference centre. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22(1):267.

doi pubmed pmc - Gore EM, Jones BS, Marques MB. Is therapeutic plasma exchange indicated for patients with gemcitabine-induced hemolytic uremic syndrome? J Clin Apher. 2009;24(5):209-214.

doi pubmed - Facchini L, Lucchesi M, Stival A, Roperto RM, Melosi F, Materassi M, Farina S, et al. Role of eculizumab in a pediatric refractory gemcitabine-induced thrombotic microangiopathy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2017;11(1):209.

doi pubmed pmc - Krishnappa V, Gupta M, Shah H, Das A, Tanphaichitr N, Novak R, Raina R. The use of eculizumab in gemcitabine induced thrombotic microangiopathy. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19(1):9.

doi pubmed pmc - Rogier T, Gerfaud-Valentin M, Pouteil-Noble C, Taleb A, Guillet M, Noel A, Broussolle C, et al. [Clinical efficacy of eculizumab as treatment of gemcitabine-induced thrombotic microangiopathy: A case report]. Rev Med Interne. 2016;37(10):701-704.

doi pubmed - Martin K, Roberts V, Chong G, Goodman D, Hill P, Ierino F. Eculizumab therapy in gemcitabine-induced thrombotic microangiopathy in a renal transplant recipient. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2019;2019(6):omz048.

doi pubmed pmc - Starck M, Wendtner CM. Use of eculizumab in refractory gemcitabine-induced thrombotic microangiopathy. Br J Haematol. 2014;164(6):894-896.

doi pubmed - Gosain R, Gill A, Fuqua J, Volz LH, Kessans Knable MR, Bycroft R, Seger S, et al. Gemcitabine and carfilzomib induced thrombotic microangiopathy: eculizumab as a life-saving treatment. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5(12):1926-1930.

doi pubmed pmc - Turner JL, Reardon J, Bekaii-Saab T, Cataland SR, Arango MJ. Gemcitabine-associated thrombotic microangiopathy: response to complement inhibition and reinitiation of gemcitabine. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2016;16(2):e119-e122.

doi pubmed - Walter RB, Joerger M, Pestalozzi BC. Gemcitabine-associated hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40(4):E16.

doi pubmed - Flombaum CD, Mouradian JA, Casper ES, Erlandson RA, Benedetti F. Thrombotic microangiopathy as a complication of long-term therapy with gemcitabine. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;33(3):555-562.

doi pubmed - Ritchie GE, Fernando M, Goldstein D. Rituximab to treat gemcitabine-induced hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a case series and literature review. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2017;79(1):1-7.

doi pubmed - Leal F, Macedo LT, Carvalheira JB. Gemcitabine-related thrombotic microangiopathy: a single-centre retrospective series. J Chemother. 2014;26(3):169-172.

doi pubmed - Klomjit N, Evans R, Le TK, Wells SL, Ortega J, Green-Lingren O, Mazepa M, et al. Frequency and characteristics of chemotherapy-associated thrombotic microangiopathy: Analysis from a large pharmacovigilance database. Am J Hematol. 2023;98(12):E369-E372.

doi pubmed pmc - Dasanu CA. Gemcitabine: vascular toxicity and prothrombotic potential. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2008;7(6):703-716.

doi pubmed - Murugapandian S, Bijin B, Mansour I, Daheshpour S, Pillai BG, Thajudeen B, Salahudeen AK. Improvement in gemcitabine-induced thrombotic microangiopathy with rituximab in a patient with ovarian cancer: mechanistic considerations. Case Rep Nephrol Dial. 2015;5(2):160-167.

doi pubmed pmc - Burns ST, Damon L, Akagi N, Laszik Z, Ko AH. Rapid improvement in gemcitabine-associated thrombotic microangiopathy after a single dose of eculizumab: case report and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2020;40(7):3995-4000.

doi pubmed - Grall M, Provot F, Coindre JP, Pouteil-Noble C, Guerrot D, Benhamou Y, et al. Efficacité de l’éculizumab dans les microangiopathies thrombotiques induites par la gemcitabine. Expérience du Centre de reference français des microangiopathies thrombotiques. Rev Médecine Interne. 2016 Dec 1;37:A136–7

- Efe O, Goyal L, Galway A, Zhu AX, Niles JL, Zonozi R. Treatment of gemcitabine-induced thrombotic microangiopathy followed by gemcitabine rechallenge with eculizumab. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6(5):1464-1468.

doi pubmed pmc - Gourley BL, Mesa H, Gupta P. Rapid and complete resolution of chemotherapy-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome (TTP/HUS) with rituximab. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;65(5):1001-1004.

doi pubmed - Nieto-Rios JF, Zuluaga-Quintero M, Higuita LM, Rincon CI, Galvez-Cardenas KM, Ocampo-Kohn C, Aristizabal-Alzate A, et al. Hemolytic uremic syndrome due to gemcitabine in a young woman with cholangiocarcinoma. J Bras Nefrol. 2016;38(2):255-259.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.