| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 10, Number 12, December 2019, pages 359-363

A Case Report of Rivaroxaban-Induced Urticaria and Angioedema With Possible Cross-Reaction to Dabigatran

Tanvi Patila, c, Christina Ikekwereb

aSalem Veterans Affair Medical Center, 1970 Roanoke Blvd, Salem, VA 24153, USA

bSoutheastern Regional Medical Center, Lumberton, NC, USA

cCorresponding Author: Tanvi Patil, Salem Veterans Affair Medical Center, 1970 Roanoke Blvd, Salem, VA 24153, USA

Manuscript submitted December 6, 2019, accepted December 30, 2019

Short title: Direct Oral Anticoagulant-Induced Angioedema

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3399

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Anticoagulants are commonly associated with hemorrhagic complications. However, rare hypersensitivity drug reactions associated with direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in form of cutaneous reactions such as urticaria as well as angioedema can have significant burden owing to increase in morbidity and mortality. Angioedema can be allergic, hereditary or idiopathic and can occur in isolation, in combination with urticaria as contributing component of anaphylaxis. With increase in the use of DOACs over warfarin as choice of anticoagulant in the treatment of atrial fibrillation (AF) as well as venous thromboembolism (VTE), recent post marketing surveillance has identified several reports of adverse drug reactions. This case report describes the clinical course of patient being treated for VTE, who experienced rivaroxaban-induced urticaria and angioedema. We further provide evidence for cross-reactivity to dabigatran manifested as significant cutaneous reaction. Patient was transitioned to warfarin with enoxaparin bridge and tolerated it well without any complications.

Keywords: Angioedema; Direct oral anticoagulants; Cutaneous reactions; Adverse drug reactions

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have eclipsed warfarin in the treatment of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) as well as venous thromboembolism (VTE) [1-3]. This is largely due to decrease in the intracranial bleed as well as simplified dosing and perioperative management along with predictable pharmacokinetics with DOACs compared to warfarin [4-6]. While hemorrhagic complications remain the most common adverse effects, the prevalence of drug reactions in patient on anticoagulants has been estimated to be between 0.01% and 7.5% [7-9]. As DOACs are increasingly utilized over time, several spontaneous reports of adverse drug reactions have become apparent in the recent pharmacovigilence systems. Early recognition of these drug reactions such as drug eruptions, vasculitis and angioedema to DOACs is critical to allow for timely management and treatment of symptoms as well as to prevent more severe adverse events such as limb ischemia, amputation or death [8-12]. We aim to describe rivaroxaban-induced urticaria and angioedema. In the same patient case, we further report cross- reactivity to dabigatran manifested as significant cutaneous reaction. The institutional review board of SALEM Veterans Health Administration Hospital determined that this case report does not meet the definition of human-subject research or exempt research, therefore review and approval by the IRB or R&D Committee was not required for this activity. Verbal consent was obtained during routine clinical care encounter which was then documented in the medical records along with the use of images provided by the patient in this case report.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 63-year-old African American man with past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, sleep apnea, aneurysm of iliac artery and prostate cancer presented to the emergency room (ER) with chief complaint of back pain rated as 9 on 10 on pain scale. Patient was being followed by outside oncologist for ongoing radiation therapy since December 2018. Patient also reported experiencing decrease in appetite with some nausea, taste alterations and > 8% weight loss over 2 months. Patient had no known drug or food allergies. Patients’ risk factors for VTE include obesity (body mass index (BMI), about 40.31 kg/m2), chronic tobacco use, increased age (> 60 years) and driving for long periods of time. Chest computed topography (CT) scan revealed right lower lobe pulmonary embolism with associated opacity and atelectasis. Upon admission, patient’s liver function tests (LFTs) were within normal limits. Complete blood count (CBC) revealed low hemoglobin of 11.8 g/dL, and absolute neutrophil count of 12.7 × 103/mm3 (elevated).

Patient was placed on intravenous heparin drip. Inpatient medications included ondansetron, hydrocodone prn for pain, and ketorolac for muscle relaxation. He also received one dose of intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone on day 2 of hospital admission. At this time, patient was transitioned to rivaroxaban 15 mg twice daily for 21 days, thereafter to be continued as 20 mg daily. Patient was discharged on day 11 and consult for pharmacist-led anticoagulation clinic was placed. On day 23, patient called the primary care provider to report that he developed generalized urticaria that appeared every couple of hours. These reactions were intermittent and self-limiting that usually appeared 1 - 2 h after taking rivaroxaban and were not specific to an area of body and moved across different areas of patients’ body. Patient also reported to have swollen hands. Some symptoms such as itching associated with rash were alleviated with the use of diphenhydramine 50 mg 2 - 3 times a day; however, no relief was reported with the swelling in his hands. Patient denied any changes in soap, detergents or intake of new food items. Patient was on low residual diet for recent small bowel obstruction. No new medications were started since the hospitalization other than rivaroxaban. Patient was instructed to continue rivaroxaban at this time along with diphenhydramine for symptom relief by the primary care provider and advised to call in case of worsening symptoms.

On day 25, patient woke up with generalized urticarial with erythema (raised plaques also known as wheals), swollen hands and feet. This quickly progressed to angioedema manifested as shortness of breath, bronchospasm as well as swelling of tongue and face and was immediately taken to ER at nearby hospital. These symptoms were confirmed based on the medical chart documentation by ER physician. The causality assessment is not very accurate due to lack of availability of serum biomarkers/immunoassay tests. Patient was discharged from the ER with prescription for 5 days of prednisone 20 mg. CBC was within normal limits; however, differential count was not checked. LFTs were not available for assessment either.

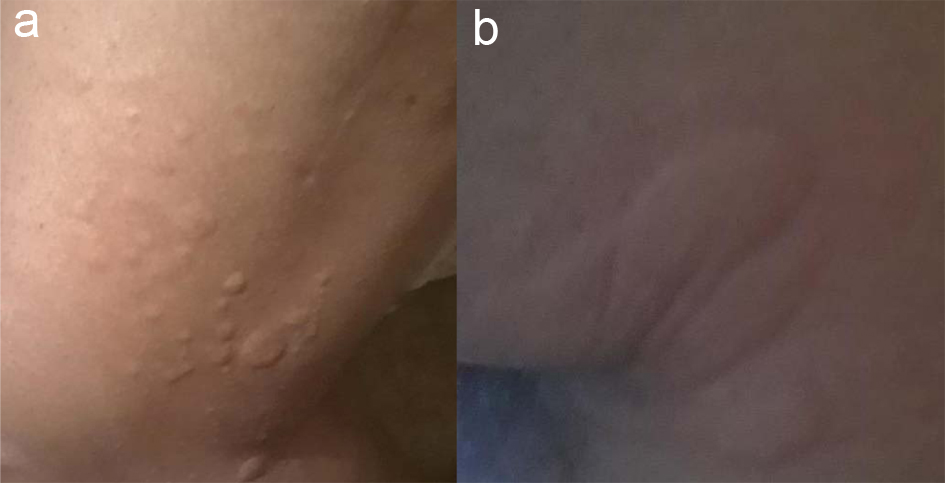

At the time, the patient was switched to dabigatran 150 mg twice daily as he could not afford to travel 2 h for international normalized ratio (INR) check and refused to take warfarin. On day 36, 10 days after dabigatran initiation, patient called the anticoagulation clinic pharmacist to report that 10 - 15 min after ingestion of dabigatran, he experienced rash with hand swelling. Patient denied swelling of lips, tongue or throat as well as shortness of breath or wheezing. Upon examination by medical provider, patient was confirmed to have developed pruritic morbilliform exanthamas eruptions on his elbows, axillae and lower extremities accompanied by swelling of hands (Fig. 1a, b). Patient had repeat LFTs and CBC which were all within normal limits. Laboratory abnormality if present would have been likely shadowed due to prednisone use. Patient continued to use diphenhydramine 2 - 3 times per day that provided some relief with the rash but did not help with the swelling. Patient was seen at the anticoagulation clinic for further management and providing counselling on available anticoagulation therapy options. With the help of social worker, patient was approved to have his labs done at a nearby hospital to avoid commuting long distance for INR monitoring. Patient was provided in depth education and was switched to warfarin with enoxaparin bridge on day 40. Patient’s cutaneous manifestations as well as swelling of extremities resolved 1 week after the drug discontinuation. At day 50, patient’s INR was 3 and enoxaparin was discontinued. Patient has remained stable on warfarin since then and continues to deny any skin reactions or swelling. Patient was assessed against Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability scale for both rivaroxaban and dabigatran.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Skin eruptions on lower extremity (a) and axillae (b) due to dabigatran. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Currently 62% of all oral anticoagulants prescribed are DOACs in patient with AF according to one large commercial insurance plan [13]. Anticoagulants-induced drug hypersensitivity reactions have been reported in the literature [14]. With superior risk-benefit profile and simpler dosing regimen, DOACs are being increasingly utilized over warfarin [15]. Angioedema is characterized by localized rapid swelling of the dermis, subcutaneous or submucosal tissues of the upper respiratory or gastrointestinal tract manifested as swelling of oral cavity, tongue or larynx leading to life-threatening airway obstruction and death [16]. A variety of adverse drug reactions including angioedema (three of the 22,222 DOAC-treated patients) have been reported in the patients taking DOACs in the pivotal randomized clinical trials [17-20]. Currently there are at least two published case reports that specifically link rivaroxaban with angioedema [21, 22]. According to the monograph, the incidences of cutaneous reactions reported in the clinical trials were: blisters (1.4%) and pruritis (1.8%) [23]. Overall incidence of cutaneous manifestations and anaphylaxis or anaphylactic shock associated with factor-XA inhibitors reported is < 0.1% [7]. In one of the case reports of rivaroxaban-induced angioedema, patient experienced generalized urticarial, erythema, severe pruritus and angioedema of orbital area and lips along with shortness of breath an airway obstruction. The drug was promptly discontinued, and patient was managed with supportive oxygen, IV antihistamines and methylprednisolone [21]. In another case report, rivaroxaban-induced hypersensivity syndrome manifested as rash, and hepatic cytolysis was reported along with histopathological evidence of spongiotic dermatitis with perivascular lymphocytes and eosinophilic infiltrates. The authors suggest that the causative effect of rivaroxaban can be established with more certainty in this case than other cases [24]. According to the eHeathme database of 137,932 people who experienced side-effects to rivaroxaban, about 88 patients (0.06%) report experiencing angioedema. Patients who are older than 60 years of age, female, who have been taking the drug for less than 1 month, who are on concomitant aspirin and have past medical history of stroke seemed more prone to experiencing angioedema. Of note, the risk of experiencing angioedema is 80% in the first month and is reduced to 0% after 5 years of initiating rivaroxaban [25, 26]. Dabigatran-induced morbilliform exanthamas has been reported as the most common drug reaction. Patients have reported to have isolated or diffuse pruritic, palpable purpura on trunk and limbs which resulted in discontinuation of dabigratran. In both cases, patient was switched to warfarin. The reaction resolved in 5 - 7 days after dabigatran discontinuation. It is pertinent to note that in most of the cases, the drug reaction was not confirmed using serum biomarkers for allergic reactions or skin testing neither were the patients re-challenged [27, 28].

Our case study provides an advantage over previously published case reports as we not only report rivaroxaban-induced urticarial and angioedema but also the evidence of cross-reactivity to dabigatran. This can provide further information to the clinicians when considering alternative treatment in the patients who develop adverse drug reaction to one of the agents in the drug class. Initially dabigatran was chosen assuming its difference in pharmacodynamics compared to rivaroxaban. It would be useful to see if patients in this scenario can benefit from using apixaban. In our case, since the patient had experienced adverse drug reaction to two out of three available DOACs at our facility, it was decided not to challenge patient with apixaban.

Well-documented case reports are essential component of post marketing safety surveillance; however, they typically suggest a probable reaction based on the Naranjo score and are inadequate for making causal inferences [29]. A recently published cohort case-crossover study by Connolly and colleagues, aimed to quantify the association between DOACs and angioedema relative to warfarin in AF patients who were drawn based on study eligibility from three different databases. This cohort reported 249 incident angioedema events among 267,681 DOAC users and 281,143 warfarin users with an average follow-up of 89 days. The hazard ratio for metanalysis of the results from three different databases comparing any DOAC versus warfarin was 0.98 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.76 - 1.2). The odds ratio for association between warfarin and angioedema in the case-crossover design was 0.91 (95% CI 0.68 - 1.21) based on 431 cases. This study did not observe a large relative increase in the angioedema rate comparing DOACs with warfarin. These findings seemed to suggest a much smaller increase in risk as compared to the previously published case reports and the pivotal trials [30]. There have been at least four cases of hypersensitivity reaction case reports published with rivaroxaban, and six case reports associated with dabigatran; however, there were not many reported cases with apixaban until recently [14]. Two patient cases were identified that reported adverse drug reactions associated with apixaban. In one case, patient experience cutaneous adverse drug reaction secondary to apixaban leading to cessation of the medication [31]. In the other case, patient experienced angioedema with significant laryngeal edema without presence of urticaria or pruritis [32].

With a score of 7 out of possible 13 points on the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability scale (Supplementary Material 1, www.journalmc.org) for rivaroxaban and 8 points for dabigatran (Supplementary Material 2, www.journalmc.org), causality between rivaroxaban/dabigatran and the observed clinical events are deemed probable in our patient case [33]. We believe that our case report can help highlight the rare adverse drug reactions associated with the DOACs to create vigilance and help with prompt intervention by clinicians.

Implication on clinical practice

Early identification and treatment of these drug reactions is critical in avoiding escalation to morbidity and mortality. Well-documented case reports that provide further clinical evidence and increase awareness amongst the clinicians treating patients with DOACs specially with the rapid increase in its use are important.

Conclusion

In this report, we have described a case of rivaroxaban-induced urticaria and angioedema manifested by severe pruritic rash, swelling of tongue and face as well as shortness of breath and bronchospasm. We further provide evidence of possible cross-reaction to dabigatran which in our patient manifested as morbilliform exanthamas along with swelling of hands. The pharmacologic mechanism by which DOACs might lead to angioedema is unclear. Further evidence to establish presence or absence of cross-reaction to apixaban may provide useful information in guiding clinical decisions when treating patients on DOACs who provide challenge for warfarin use. Additionally, use of skin patch testing at different concentrations to all factor-Xa inhibitors under direct medical supervision can also be considered given the severity of reaction to the suspected agent. Furthermore, use of immunoglobulin E specific testing may confirm the causal relationship between DOACs and these adverse drug reactions. DOACs are structurally different and the manifestations developed also differ in pathologies. Hence future studies are necessary to explore the implications on clinical practice in patient developing adverse drug events to one of the DOACs.

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Supplementary Material 1. Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale for Rivaroxaban.

Supplementary Material 2. Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale for Dabigatran.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have any conflicts to disclose. The results of this study do not represent the views of Federal government or Veterans Administration.

Informed Consent

Verbal consent to use this case for publication was obtained from the patient during routine clinical care encounter which was then documented in the medical records along with the use of images provided by the patient in this case report. This was deemed as being appropriate by the IRB for publication purposes.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed towards the drafting of the case report and offered comments to the previous versions for important intellectual content. The main draft of manuscript was written by Tanvi Patil (primary author). Co-author has agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

| References | ▴Top |

- Barnes GD, Lucas E, Alexander GC, Goldberger ZD. National trends in ambulatory oral anticoagulant use. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1300-1305 e1302.

doi pubmed - Badreldin H, Nichols H, Rimsans J, Carter D. Evaluation of anticoagulation selection for acute venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2017;43(1):74-78.

doi pubmed - Kjerpeseth LJ, Ellekjaer H, Selmer R, Ariansen I, Furu K, Skovlund E. Trends in use of warfarin and direct oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation in Norway, 2010 to 2015. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73(11):1417-1425.

doi pubmed - Chai-Adisaksopha C, Crowther M, Isayama T, Lim W. The impact of bleeding complications in patients receiving target-specific oral anticoagulants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood. 2014;124(15):2450-2458.

doi pubmed - Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Anderson JM, Arnold DM, Bates SM, Blostein M, Carrier M, et al. The Perioperative Anticoagulant Use for Surgery Evaluation (PAUSE) study for patients on a direct oral anticoagulant who need an elective surgery or procedure: design and rationale. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117(12):2415-2424.

doi pubmed - Yeh CH, Fredenburgh JC, Weitz JI. Oral direct factor Xa inhibitors. Circ Res. 2012;111(8):1069-1078.

doi pubmed - Hofmeier KS. Hypersensitivity reactions to modern antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs. Allergo J Int. 2015;24(2):58-66.

doi pubmed - Harenberg J, Hoffmann U, Huhle G, Winkler M, Bayerl C. Cutaneous reactions to anticoagulants. Recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2(2):69-75.

doi pubmed - Jorg I, Fenyvesi T, Harenberg J. Anticoagulant-related skin reactions. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2002;1(3):287-294.

doi pubmed - Raj K, Collins B, Rangarajan S. Purple toe syndrome following anticoagulant therapy. Br J Haematol. 2001;114(4):740.

doi pubmed - Talmadge DB, Spyropoulos AC. Purple toes syndrome associated with warfarin therapy in a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(5):674-677.

doi pubmed - Nazarian RM, Van Cott EM, Zembowicz A, Duncan LM. Warfarin-induced skin necrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(2):325-332.

doi pubmed - Desai NR, Krumme AA, Schneeweiss S, Shrank WH, Brill G, Pezalla EJ, Spettell CM, et al. Patterns of initiation of oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation- quality and cost implications. Am J Med. 2014;127(11):1075-1082 e1071.

doi pubmed - Vu TT, Gooderham M. Adverse drug reactions and cutaneous manifestations associated with anticoagulation. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21(6):540-550.

doi pubmed - da Silva RM. Novel oral anticoagulants in non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2014;12(1):3-8.

doi pubmed - Jaiganesh T, Wiese M, Hollingsworth J, Hughan C, Kamara M, Wood P, Bethune C. Acute angioedema: recognition and management in the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med. 2013;20(1):10-17.

doi pubmed - Moellman JJ, Bernstein JA, Lindsell C, Banerji A, Busse PJ, Camargo CA, Jr., Collins SP, et al. A consensus parameter for the evaluation and management of angioedema in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(4):469-484.

doi pubmed - Boehringer Ingelheim. Randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy (RE-LY) with dabigatran etexilate. ClinicalTrials.gov [cited 16 Aug 2018]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00262600.

- Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, LLC. An efficacy and safety study of rivaroxaban with warfarin for the prevention of stroke and non-central nervous system systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. ClinicalTrials.gov [cited 16 Aug 2018]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00403767.

- Bristol-Myers Squibb. Apixaban for the prevention of stroke in subjects with atrial fibrillation. ClinicalTrials.gov [cited 16 Aug 2018]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00412984.

- Altin C, Ozturkeri OA, Gezmis E, Askin U. Angioedema due to the new oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban. Ann Card Anaesth. 2014;17(2):173-174.

doi pubmed - Wells PS, Prins MH, Levitan B, Beyer-Westendorf J, Brighton TA, Bounameaux H, Cohen AT, et al. Long-term anticoagulation with rivaroxaban for preventing recurrent VTE: a benefit-risk analysis of EINSTEIN-extension. Chest. 2016;150(5):1059-1068.

doi pubmed - Xarelto [prescribing information]. Titusville, NJ. Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; January 2019.

- Chiasson CO, Canneva A, Roy FO, Dore M. Rivaroxaban-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2017;70(4):301-304.

doi pubmed - Investigators E-P, Buller HR, Prins MH, Lensin AW, Decousus H, Jacobson BF, Minar E, et al. Oral rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(14):1287-1297.

doi pubmed - eHeathMe: Real-world drug outcomes available at: https://www.ehealthme.com/extended/ds/xarelto/angioedema/#print.

- Eid TJ, Shah SA. Dabigatran-induced rash. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68(16):1489-1490.

doi pubmed - Whitehead H, Boyd JM, Blais DM, Hummel J. Drug-induced exanthem following dabigatran. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(10):e53.

doi pubmed - Nissen T, Wynn R. The clinical case report: a review of its merits and limitations. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:264.

doi pubmed - Connolly JG, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ, Gagne JJ. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants and angioedema: a cohort and case-crossover study. Drug Saf. 2019;42(11):1355-1363.

doi pubmed - Albalbissi A, Balagoni H, Treece J, et al. Cutaneous adverse drug reaction due to apixaban [abstract no. P033]. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119(5 Suppl 1):S27.

doi - Williamson A, Vaughn CA, Tulunay-Ugur OE. Angioedema Involving the Larynx after Starting Apixaban. OTO Open. 2019;3(1):2473974X18805431.

doi pubmed - Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, Janecek E, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239-245.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.