| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 12, Number 4, April 2021, pages 149-151

Giant Cell Tumor of the Temporal Bone With Skull Base and Middle Ear Extension

Ilson Sepulvedaa, e, Jose Alzerrecab, Pamela Villalobosc, J. Patricio Ulload

aFinis Terrae University School of Dentistry, Radiology Department ENT-Head and Neck Surgery, Maxilofacial and Nuclear Medicine Services, General Hospital of Concepcion, San Martin Av. 1436, Concepcion, Chile

bENT Department, Clinic of De los Andes University, Santiago, Chile

cPathology Department, University of Concepcion School of Medicine, Concepcion, Chile

dDepartment ENT-Head and Neck Surgery, General Hospital of Concepcion, University of Concepcion School of Medicine, Concepcion, Chile

eCorresponding Author: Ilson Sepulveda, Finis Terrae University School of Dentistry, Radiology Department ENT-Head and Neck Surgery, Maxilofacial and Nuclear Medicine Services, General Hospital of Concepcion, San Martin Av. 1436, Concepcion, Chile

Manuscript submitted December 1, 2020, accepted December 31, 2020, published online February 8, 2021

Short title: GCT of the Temporal Bone

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3627

| Abstract | ▴Top |

We report on a patient who presented to the ear, nose, and throat (ENT) clinic with an 8-month-old left non-pulsatile tinnitus. Imaging studies, Neck computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed soft tissue mass in the left middle ear with invasion to the middle cranial fossa and external auditory canal.

Keywords: Temporal bone; CT; MRI; Giant cell; Tumor

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Giant cell tumor (GCT) is a benign and locally aggressive bone tumor that can be found more frequently in the metaphyseal region of the long bones [1]. In the skull it is very rare with few cases in temporal bone. It is more common in women in the fourth decades of life with symptoms associated to tumor’s location, including headache and cranial nerve involvement [2]. On images it appears eroding the surrounding bone as it expands [3]. Surgical treatment is the best choice and its prognosis improves with free margins in radical excision. The role of the chemo- and radiation therapy remains controversial [4, 5].

| Case Report | ▴Top |

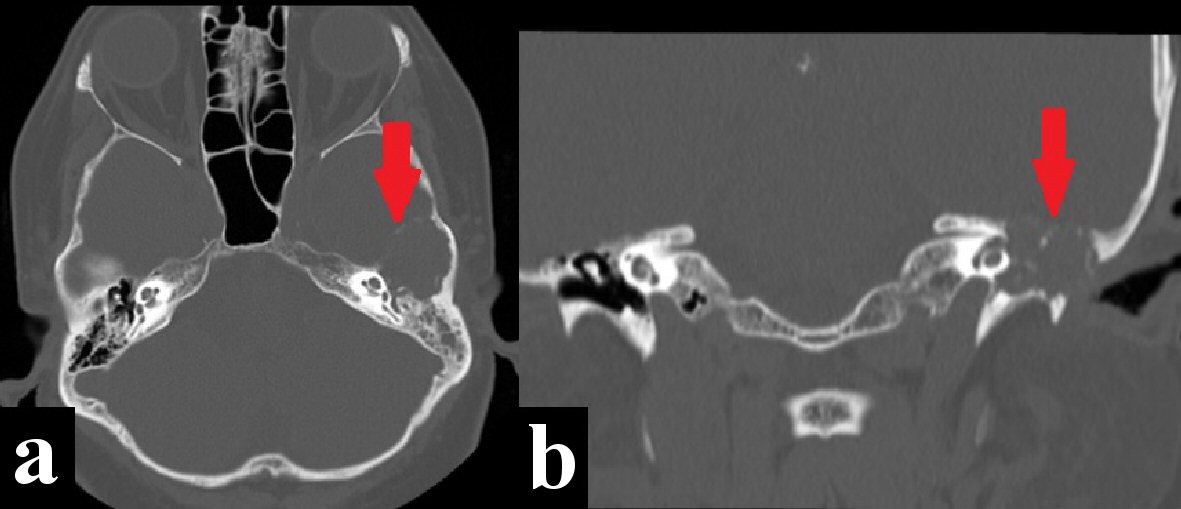

A 64-year-old woman with medical history of chronic arterial hypertension presented to the ENT clinic with an 8-month-old left non-pulsatile tinnitus. In the last month she relates left otalgia, dizziness, postural instability and increase in the support base. No vertigo, otorrhea or vegetative symptoms. A temporal bone computed tomography (CT) was performed revealing an inhomogeneous soft tissue mass in the left middle ear, showing minimal calcifications within, and invasion to the middle cranial fossa and external auditory canal. Eroding the lateral semicircular canal, basal turn of the cochlea, tympanic portion of the VII cranial nerve, ossicular chain, and tegmen tympani was demonstrated (Fig.1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Temporal bone computed tomography (CT) bone window shows a destructive and expansive process eroding the left middle skull base, tegmen tympani, ossicular chain, Scutum, basal turn of the cochlea, and tympanic portion of the facial nerve (red arrows). (a) Axial view. (b) Coronal view. |

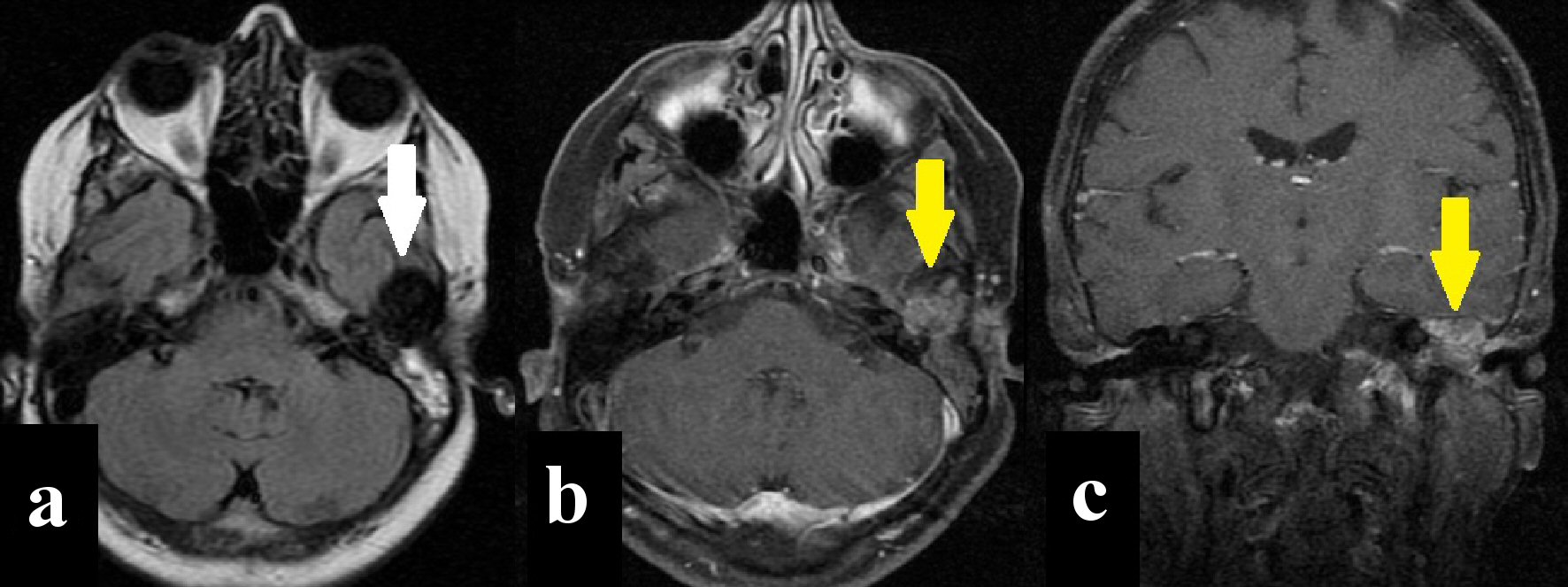

Subsequently, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study was performed revealing in T1 and T2 sequences a solid extra-axial hypointense expansive process in the left middle skull base, well delimited, and involvement of the ipsilateral middle ear. An additional MRI T1 sequence following administration of gadolinium contrast material showed moderate enhancement (Fig. 2)

Click for large image | Figure 2. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). (a) Axial T2-FLAIR sequence shows solid extra-axial mass with low signal (white arrow). (b, c) Axial and coronal T1 Fast Sat sequence showing moderate enhancement after intravenous contrast administration (yellow arrows). |

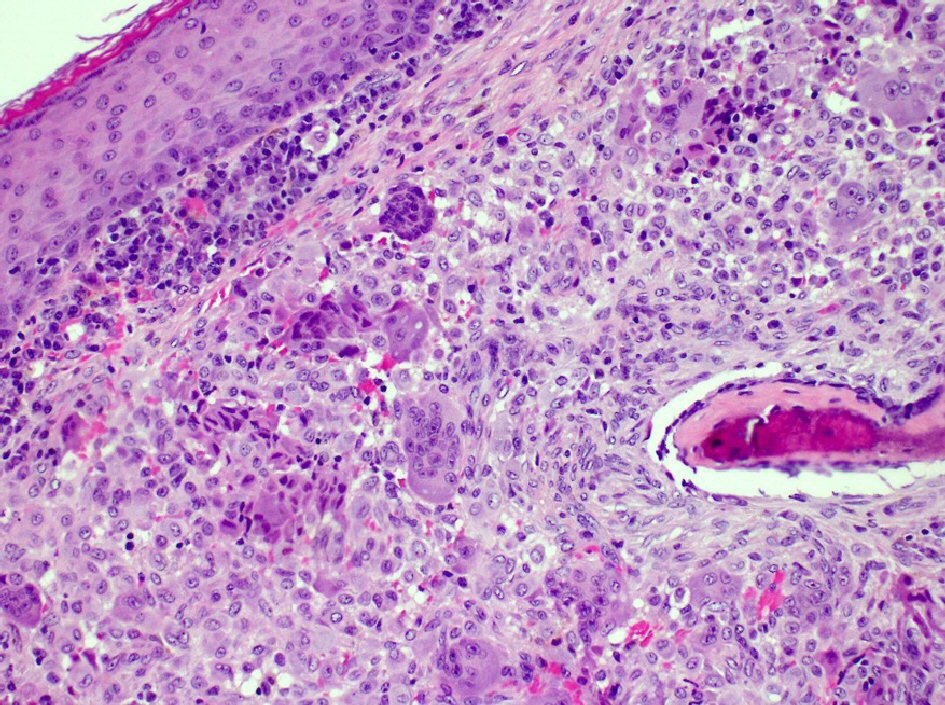

Following the results of the imaging studies, surgical excision was recommended as the best treatment of choice. Radical mastoidectomy with complete tumor resection and facial nerve preservation was performed. Subsequently, biopsy findings of the surgical specimen revealed osteoclast-like GCT with free surgical margins (Fig.3). Currently, 3 years after surgery, the patient has remained disease-free with no signs of recurrence.

Click for large image | Figure 3. H&E stain: fragments of stromal lesion with osteoclast- like giants cells. H&E: hematoxylin and eosin. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

GCT derived from non-osteogenic stromal cells of bone marrow of endochondral bone [6]. It represents approximately 3-7% of all primary bone tumors and 20% of the benign bone neoplasms with a malignant phenotype in 5-10% of cases [1, 7]. It is most commonly seen in the fourth or fifth decades of life with a slight female predominance with a ratio of 3:2 [3, 8]. Usually it arises in the long bones, such as distal radius and femur and proximal tibia and fibula [7]. Skull is a rare location for GCT, with the sphenoid bone being the most common site followed by the temporal bone [2, 5]. There are three theories in relation to origin of the GCT: neoplastic, inflammatory and traumatic; none of them has been confirmed in the literature [6].

Histologically, GCT has three cells types: osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cells, round mononuclear cells, and spindle-shaped, fibroblast-like mononuclear cells [8]. There is no atypical mitosis, which supports its benign nature [9]. However, other tumors are also rich in giant cells such as chondroblastomas, aneurysmal bone cysts and giant-cell reparative granulomas, which makes it difficult to make a correct pathological diagnosis [8].

On the temporal bone, GCT is usually silent growing until attaining a large size before clinical symptoms develop, often delaying the diagnosis [5]. The symptoms are associated with conductive hearing loss, vertigo, and tinnitus, fullness of ear, otalgia, facial weakness and obstruction of the eustachian tube [2].

GCT does not have specific radiological characteristics. On temporal bone CT appears, because of its vascular nature, as an enhancing expanding lytic and destructive lesion, sometimes it shows soap bubble appearance which may extend to adjacent soft tissues, dura mater or intracranial extension [3, 5]. MRI images demonstrated an intermediate signal on T1-weighted images and low signal in both T2 and diffusion-weighted images, and heterogeneous enhancement after intravenous contrast administration (gadolinium) [4].

Complete and radical resection is the treatment of choice, but is often difficult in the temporal bone if there is intracranial extension and due to intimate relationship to vital structures and morbidity associated with their sacrifice [9]. So, adjuvant radiotherapy is indicated, which however, is still controversial because some authors state that it may trigger malignant transformation on residual tumor tissue [1, 7]. Chemotherapy could be used in cases of unresectable tumor or when surgical resection is likely to result in severe morbidity. Denosumab demonstrated efficacy in disease and symptom control of GCT [10]. Bisphosphonates can be used to mitigate bone destruction and prevent local recurrence following surgery [11]. In our case, adjuvant radiotherapy was not required because the tumor was completely removed by surgery itself.

GCT is benign tumor with a good prognosis after complete resection [4]. In case of a partial resection, rates of recurrence increase to 40-60% [3]. It has potential malignant transformation commonly to fibrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, or malignant fibrous histiocytoma [7, 9]. In nearly 3% of the cases it presents as spontaneous primary malignant tumors with potential to metastasize in about 5-10% of the cases, principally to the lung by hematogenous dissemination [11].

The differential diagnosis includes giant-cell reparative granuloma, both with similar radiographic appearance. In the middle ear lesions we must consider cholesteatomas, paragangliomas and Langerhans cell histiocytosis [2].

Conclusions

GCT of the temporal bone is an uncommon entity with clinical and radiographic features nonspecific, even with currently available imaging tools, therefore the diagnostic and treatment are challenging. A deep knowledge about clinical, radiologic, and histopathology examinations, benign nature and the probability of malignant transformation, leads to better treatment for each case, always aiming to the complete resection of the tumor and total control of the disease.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

I. Sepulveda: images and literature review; J. Alzerreca: clinic case; P. Villalobos: biopsy; J. P. Ulloa: literature review.

Data Availability

Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

| References | ▴Top |

- Tamura R, Miwa T, Shimizu K, Mizutani K, Tomita H, Yamane N, Tominaga T, et al. Giant cell tumor of the skull: review of the literature. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2016;77(3):239-246.

doi pubmed - Miller MA, Kesarwani P, Crane BT. Autophony in a patient with giant cell tumor of the temporal bone. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37(7):e238-239.

doi pubmed - Koo T, Danner C. A rare case of giant cell tumor of the temporal bone. Otolaryngology Case Reports. 2020;15:100160.

doi - Iizuka T, Furukawa M, Ishii H, Kasai M, Hayashi C, Arai H, Ikeda K. Giant cell tumor of the temporal bone with direct invasion into the middle ear and skull base: a case report. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2012;2012:690148.

doi pubmed - Hsu SW, Hueng DY, Lin HC, Liu MY, Ma HI, Hsia CC. Giant cell tumor of the temporal bone. Formosan Journal of Surgery. 2013;46(1):30-32.

doi - Jain S, Sam A, Yohannan DI, Kumar S, Joshi D, Kumar A. Giant cell tumor of the temporal bone—an unusual presentation. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115(5):646-648.

doi pubmed - Borges BB, Fornazieri MA, Bezerra AP, Martins LA, Pinna Fde R, Voegels RL. Giant cell bone lesions in the craniofacial region: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2012;2(6):501-506.

doi pubmed - Kaya I, Benzer M, Turhal G, Sercan G, Bilgen C, Kirazli T. Giant Cell Tumor of the Temporal Bone and Skull Base: A Case Report. J Int Adv Otol. 2018;14(1):151-154.

doi pubmed - Jain A, Singh I, Shankar R, Varshney D. Giant cell tumour of temporal bone and infratemporal fossa: a rare case. Head Neck Pathol. 2020;14(2):503-506.

doi pubmed - Nicoli TK, Saat R, Kontio R, Piippo A, Tarkkanen M, Tarkkanen J, Jero J. Multidisciplinary approach to management of temporal bone giant cell tumor. J Neurol Surg Rep. 2016;77(3):e144-e149.

doi pubmed - Scotto di Carlo F, Whyte MP, Gianfrancesco F. The two faces of giant cell tumor of bone. Cancer Lett. 2020;489:1-8.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.