| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 13, Number 5, May 2022, pages 207-211

A Case of Delayed COVID-19-Related Macrophage Activation Syndrome

Abdelnassir Abdelgabara, b, Mohammed Elsayeda

aAcute Medicine Department, Diana, Princess of Wales Hospital, Grimsby DN33 2BA, UK

bCorresponding Author: Abdelnassir Abdelgabar, Acute Medicine Department, Diana, Princess of Wales Hospital, Grimsby DN33 2BA, UK

Manuscript submitted January 24, 2022, accepted March 25, 2022, published online April 12, 2022

Short title: Delayed COVID-19-Related MAS

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3903

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Although coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is primarily a respiratory illness, clinical experiences have shown that almost no system is exempted. The severity of the disease can also range from mild presentation with complaints such as headache, aches and pains, taste and sense of smell disturbances to a more severe presentation with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) that necessitate admission to intensive care units. In such severe presentation, hypercytokinemia, typically found in cytokine storm syndrome (CSS), particularly macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) is often present. CSS can result from diverse, heterogeneous conditions of different clinical phenotypes, such as infections, hematological, rheumatological or iatrogenic conditions leading to systemic hyperinflammation. Some clinical and laboratory findings may give clues to such a highly lethal syndrome and allow early diagnosis and introduction of effective therapy. In this case we describe a COVID-19 pneumonia patient who was discharged home following improvement in his respiratory symptoms to present few days later with a fatal form of CSS, presenting with ARDS, fulminant hepatic failure and coagulopathy.

Keywords: Cytokines storm syndrome; Macrophage activation syndrome; COVID-19; Hyperinflammatory syndrome

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a pandemic that was first reported in China. Infection with the virus results in a great variety of symptoms across the spectrum, from symptomless disease to a severe lethal syndrome. Although this severe form can occur in healthy individuals at any age, it is predominantly more common in elderly patients and those who are immunocompromised. Other risk groups for such a severe presentation include obesity, black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) population and metabolic syndrome patients [1]. The natural history of the most common form of COVID-19 presentation is of flue-like symptoms, fever, impaired or complete loss of sense of smell and taste, headache and myalgia. Common laboratory findings include high C-reactive protein (CRP), reduced lymphocyte count and high D-dimer level. Radiologically diffuse patchy infiltrate and ground glass appearance are frequently seen on plain X-rays and computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, respectively. Confirmation of the diagnosis is made by positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for coronavirus in nasopharyngeal swabs of symptomatic patients.

COVID-19, particularly in those presenting with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), may result in marked inflammation and hyperimmune state with elevated cytokines [2]. This results from COVID-19 directly infecting macrophages and monocytes through the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE2) receptor, resulting in macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) [3], for which a high level of ferritin is considered to be a marker [4]. CSS can not be considered as a separate disease entity, but rather a common final point of different initial pathologies. These pathologies could be infections, hematological, rheumatological, autoimmune or even of iatrogenic origins. Although this syndrome, observed in COVID-19, does share many laboratory and clinical features of MAS occurring in sepsis and other hematological and rheumatological conditions, significant differences still exist. Therefore, COVID-19-specific hyperinflammatory syndrome criteria have been proposed for more precise diagnosis and differentiation from other causes [5].

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

An obese, 54-year-old Caucasian male, with a body mass index of (31.8) and no significant past medical history, was admitted to our hospital 5 days following a positive coronavirus nasopharyngeal swab test in the community. He was admitted with fever, rigors, persistent cough, myalgia and shortness of breath, with no chest pain, palpitation, or hemoptysis. Relevant to his presentation is that he is non-smoker, does not drink alcohol and has no history of liver disease or other co-morbidities. On clinical examination, the patient looked unwell with a temperature of 39.5 °C, low O2 saturation at 88% on room air, with blood pressure of 140/82 mm Hg, a heart rate of 95/min, respiratory rate of 22/min and bibasilar crackles, no pleural, pericardial rub or deep vein thrombosis. The rest was unremarkable.

Diagnosis

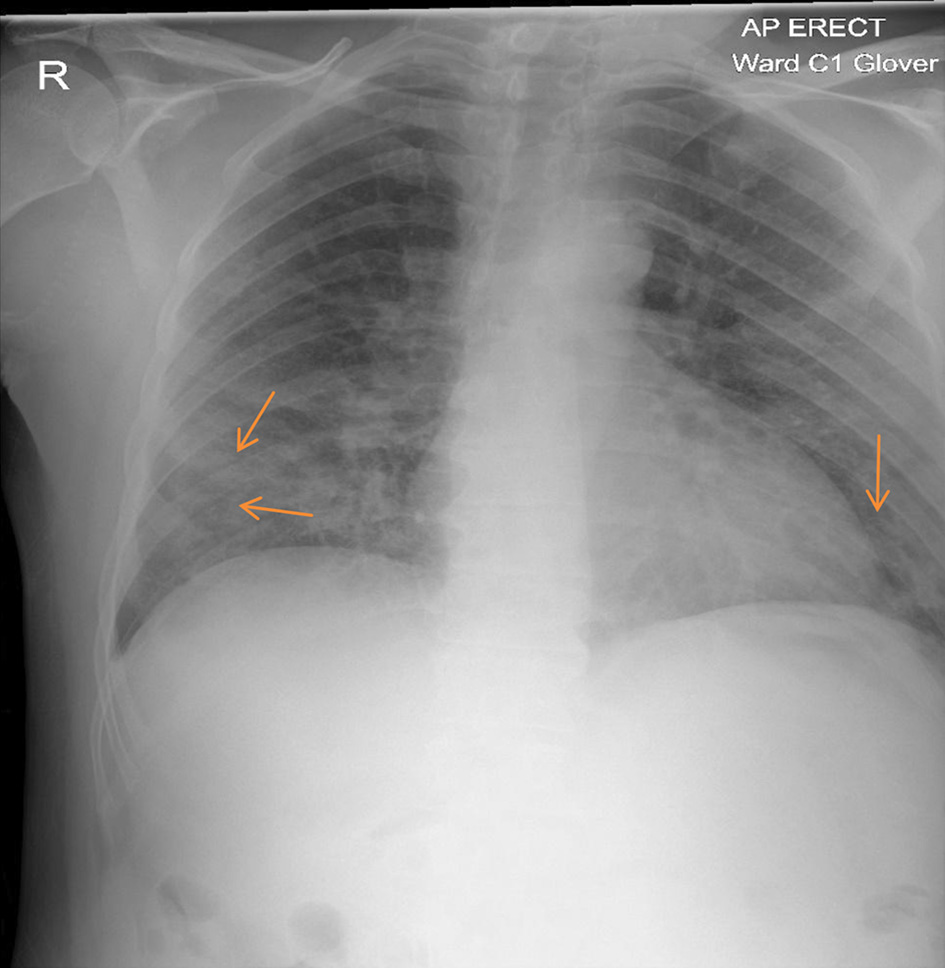

Laboratory investigations showed lymphopenia 0.59 (1.0 - 3.6 × 109/L), high CRP at 244 (0 - 5 mg/L), and ferritin 1,620 (40 - 405 µg/L). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was elevated at 334 (135 - 225 µ/L). Clotting, liver and renal functions were all normal. Atypical pneumonia screen and blood cultures were both negative. Arterial blood gas (ABG) was consistent with type 1 respiratory failure. Chest X-ray (CXR) (Fig. 1) showed bilateral patchy consolidation. The patient was diagnosed with COVID-19 pneumonia.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Chest X-ray: increased air space shadowing (arrows) in the mid and lower zones with a peripheral pattern suggestive of COVID-19 pneumonia. COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019. |

Treatment

He was treated with O2 therapy, intravenous antibiotics, dexamethasone and remdesivir. While inpatient he needed high-flow O2 (15 L/min) at some stage in the high dependency unit, during which tocilizumab was given. The patient made a good recovery, stepped down to the ward and was discharged home with O2 saturation of more than 94% on room air and with dramatic improvement in his inflammatory markers.

Follow-up and outcomes

Two weeks following his discharge, he was readmitted with being generally unwell, with extreme fatigue, a poor appetite, reduced oral intake and a high temperature. His heart rate was 132/min, pyrexial at 38.2 °C, hypotensive with blood pressure of 92/52 mm Hg, and tachypnea with respiratory rate of 32/min. His Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was 14/15, icterus positive in eyes, peripherally cyanosed, positive flapping tremors, encephalopathic, with a distended tender abdomen. He was in severe type 1 respiratory failure, with pO2 of 5.7 (11 - 13 kPa), pCO2 of 4.7 (4.8 - 6.00 kPa) and severe metabolic acidosis with a PH of 6.97, lactate of 13.8 mmol, base excess of -22.5 and bicarbonate of 7.9 mmol/L. He was also in severe acute kidney injury with hyperkalemia with potassium of 6.4 (3.5 - 5.5 mmol/L) and high creatinine of 200 (59 - 104 µmol/L) and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (EPI) at 32 (90 - 200 mL/min). Liver function tests showed acute hepatic injury with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 13,685 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 23,118 U/L, bilirubin of 83 (0 - 21 µmol/L), amylase of 413 (28 - 100 U/L), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 322 (30 - 130U/L), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) of 930 (10 - 71 U/L), and albumin of 28 (35 - 50 g/L). Paracetamol level was undetectable. Coagulopathy was impaired with high international normalized ratio (INR) at 2.1 (0.9 - 1), and raised activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) at 50 s (24.6 - 36.6 s). D-dimer level was high and platelets were low at 65 (150 - 400 × 109/L). CRP was 55 mg/L. Ferritin was extremely high at 99,999 µg/L (40 - 405 µg/L).

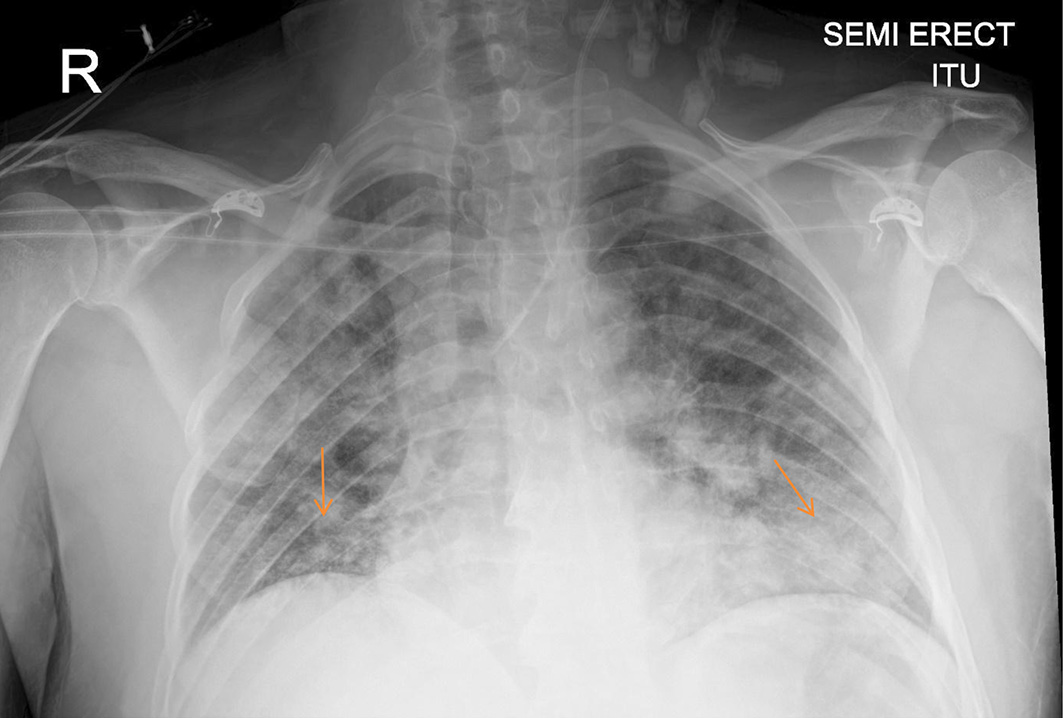

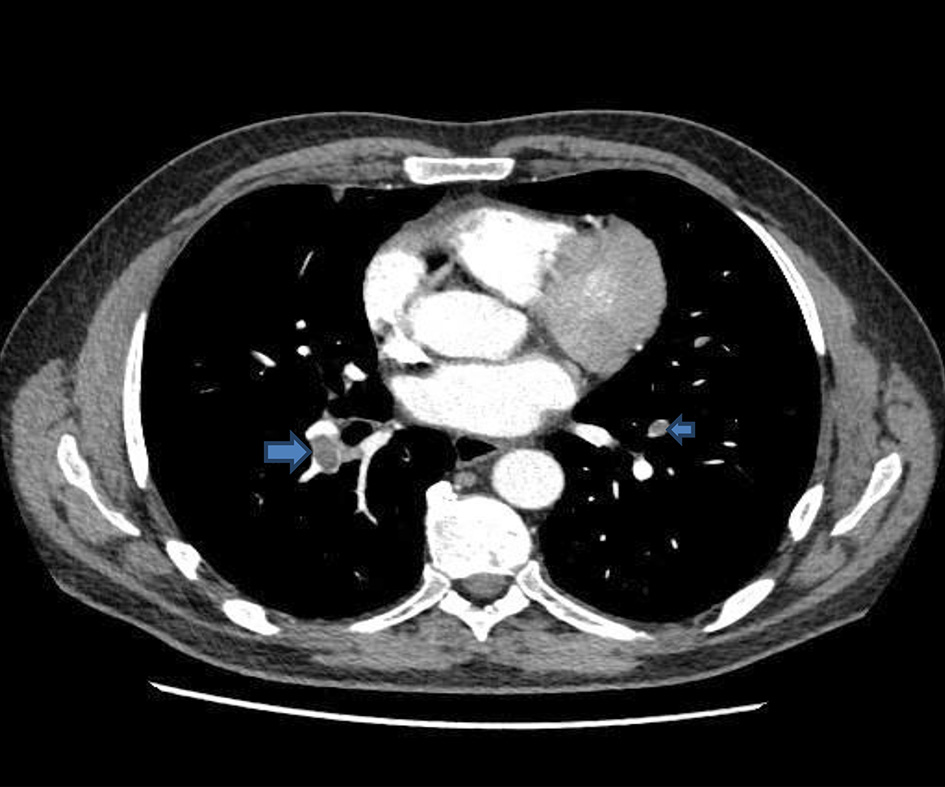

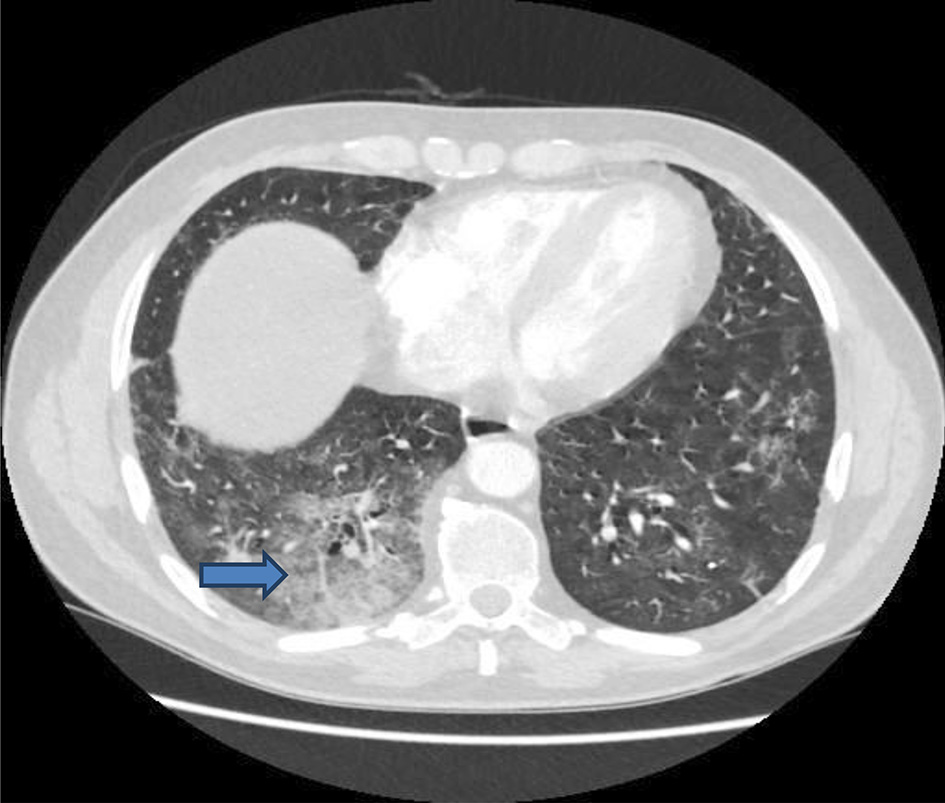

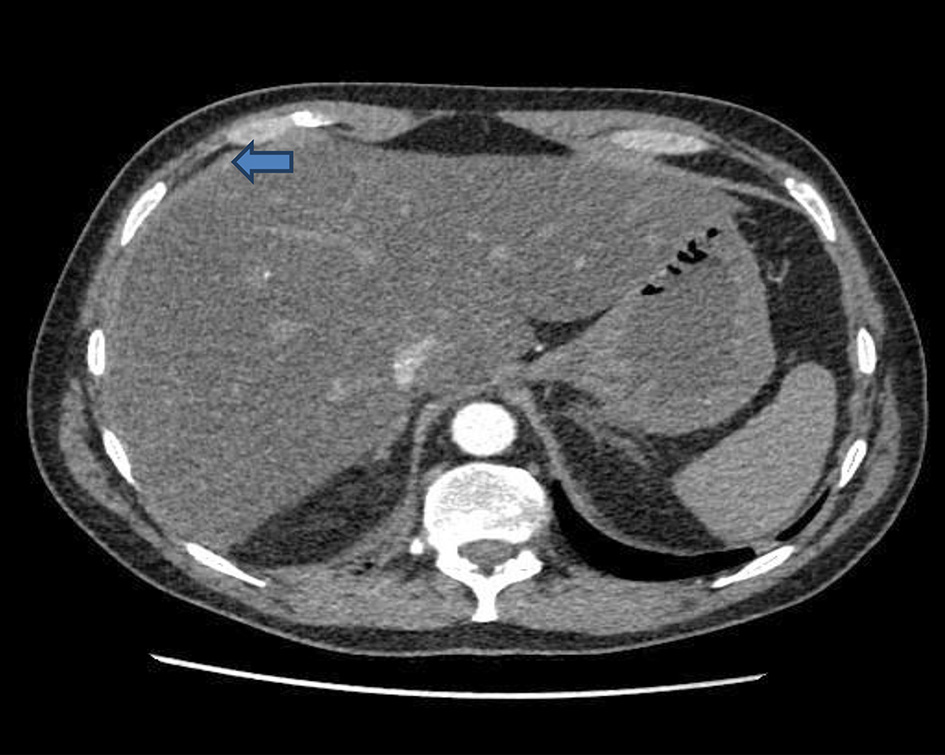

He was admitted directly to the intensive care units (ICUs) for hemodynamic and respiratory support. A central venous catheter was inserted and was put on high-flow oxygen with a potential for intubation and ventilation. Intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam, intravenous fluids, human albumin serum, fresh frozen plasma, dexamethasone, proton pump inhibitors and bicarbonate were administered intravenously. CXR (Fig. 2) and CT of abdomen and pelvis with contrast were done (Figs. 3-5). The patient condition was discussed with the regional hepatology and liver transplant unit and in view of the multiorgan failure they advised best supportive care with regular update on his condition. Few hours later the patient further dropped his GCS and became more hypotensive with mean arterial pressure of 60 mm Hg. At this stage he was intubated and ventilated. Sadly he developed cardiac arrest and died within 24 h of his readmission.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Chest X-ray: extensive abnormal densities (arrows) throughout the lung fields are consistent with COVID-19 infection. COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. CT of abdomen and pelvis: multiple pulmonary emboli (arrows). CT: computed tomography. |

Click for large image | Figure 4. CT of chest: pulmonary changes suggestive of evolving COVID-19 pneumonitis with some confluent consolidation in the right base (arrow). CT: computed tomography; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019. |

Click for large image | Figure 5. CT of abdomen: diffuse fatty change and perihepatic edema (arrow) are in keeping with acute hepatitis. CT: computed tomography. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

COVID-19 is a multisystem disorder with a wide spectrum of clinical and laboratory manifestations. Among the many targets involved in this disease process is the direct involvement of the macrophages, in a process that may lead to hyperinflammatory syndrome with ARDS and end organ damage [6].

Contrary to what most clinicians understand, CSS resulting in ARDS and multiorgan failure can suddenly occur during the recovery process [7]. Our patient is an example of this. It is not necessarily that such patients show severe clinical manifestations in the early stage of the disease. Some of these patients only showed subtle presentation such as mild fever, cough, aches and pains, before rapidly developing this syndrome. It is thought that dysregulated and excessive immune responses is the main trigger for MAS. Of these dysregulated responses is the delayed release of interferons, in the early stages of COVID-19 infection hindering the early antiviral defence mechanisms [8]. This is followed by excessive release of cytokines such as interleukin-6 and chemokines, which both result in many inflammatory cells, neutrophil and monocytes crowding in the respiratory epithelial cells ultimately leading to lung injury, ARDS and other extrapulmonary organs failure [9].

Recently understanding of this syndrome has increased with a progressive increase in case reports of different presentations of COVID-19-associated hyperinflammatory features. Despite this, hypeinflammatory syndrome, even in more severe COVID-19 patients, is rare and may account for less than 5% of adult patients. However, this could be an underestimation as most cases lacked information about the diagnostic criteria, since such criteria or tests are not routinely performed in clinical practice [10]. Another reason for this underestimation is that the clinical symptoms and signs of these hyperinflammatory syndromes, such as CSS, are non-specific and may be quite similar to sepsis, resulting in considerable difficulty attributing such a presentation to CSS [11, 12]. There is also a lack of universality of the diagnostic criteria of such syndromes, partially due to lack of knowledge about the syndrome and the limitations and insufficiencies of the criteria themselves, therefore these criteria are under continuous evaluation and evolution [13]. Another factor contributing to the underestimation of hyperinflammatory syndrome is the potential lack of sensitivity in using some of the existing scores in COVID-19 patients [10].

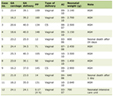

Due to all these limitations, some criteria for hyperinflammatory syndrome in COVID-19 are proposed Table 1 [5].

Click to view | Table 1. Patient Results Against Criteria for Hyperinflammatory Syndrome |

Criteria proposed for hyperinflammtory syndrome associated with COVID-19 [5] included: 1) Fever (defined as temperature more than 38.0 °C). 2) Macrophage activation (defined as ferritin concentration of 700 µg/L or more). 3) Hematological dysfunction (defined as neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio of 10 or more, or both hemoglobin concentration of 9.2 g/dL or less and platelets count of 110 × 109 cells per L or less. 4) Coagulopathy defined as D-dimer concentration of 1.5 µg/mL or more. 5) Hepatic injury (defined as LDH concentration of 400 U/L or more, or an AST concentration of 100 U/L or more). 6) Cytokinemia defined as interleukin-6 of 15 pg/mL or more or a triglyceride concentration of 150 mg/dL or more or a CRP concentration of 15 mg/dL or more.

The rapid deterioration of our patient with high temperature, coagulopathy, severe hepatic injury and extremely high ferritin makes MAS in the context of COVID-19 the most likely diagnosis. He also satisfied most of the proposed criteria for hyperinflammatory syndrome associated with COVID-19 (Table 1) [5].

Treatment strategy of CSS

Inflammation itself is an important part of an effective immune response. However, COVID-19 induces excessive response that leads to lung and other organs injury. Therefore, effective control of CSS depends on timely intervention with means of immunomodulatory and cytokines antagonists. Such intervention includes corticosteroids and interleukin antagonists such as tocilizumab, which can both lead to early improvements, reducing fever, improving oxygenation and reducing lung infiltrates volume [14]. General supportive measures such as fluids, oxygen therapy and intravenous antibiotics should simultaneously be used. Although there are a lot of similarities in the broader characteristics of CSS, irrespective of the nature of the initial causative insult, being infectious, autoimmune or iatrogenic, significant differences still exist. These differences are undoubtedly contributing to the need of different therapies to cover the landscape of this wide-ranging syndrome [11]. As much work as has been done to propose specific features of COVID-19-related hyperinflammatory syndrome [5], a lot of work is also looking into the precise therapies for the different forms of such a diverse syndrome. Such precise personalized therapies will require the knowledge of the similarities and differences between the wide range of conditions under the umbrella of CSS. Of equal importance is identifying the individual trigger in each case and understanding the single main effector cytokine leading to the exaggerated and amplified immune response. A lot of studies and investigations, in this area, are conducted with pace and enthusiasm leading to progress in understanding CSS. This will hopefully ultimately lead to novel cytokine-blocking strategies and hence precision therapy [11].

Conclusion

This case demonstrates that patients who show some clinical or laboratory features of MAS, during their early course of the disease, might drift at any stage into a delayed lethal form of MAS. This emphasises the need for risk stratification of such patients and hence arranging some form of follow-up to these high-risk patients, which can be virtual. This will lead to early recognition and accordingly taking the appropriate steps for early effective management including readmission to the appropriate health care facility.

Learning points

COVID-19 is a heterogeneous disease with a wide spectrum of symptoms presentation. Some patients presenting with subtle symptoms may still develop a fatal form of MAS, after what is seemingly a good recovery. Effort should be made for early identification of these high-risk patients before it is too late.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Consent was obtained from the deceased next of kin.

Author Contributions

Dr Abdelnassir Abdelgabar perfomed literature search related to the case, and he also wrote the case report. Dr Mohammed Elsayed transferred the images into the text, created the tables and contributed to the case report.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Vepa A, Bae JP, Ahmed F, Pareek M, Khunti K. COVID-19 and ethnicity: A novel pathophysiological role for inflammation. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(5):1043-1051.

doi pubmed - Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ, Hlh Across Speciality Collaboration UK. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033-1034.

doi - Merad M, Martin JC. Pathological inflammation in patients with COVID-19: a key role for monocytes and macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(6):355-362.

doi pubmed - Lambotte O, Cacoub P, Costedoat N, Le Moel G, Amoura Z, Piette JC. High ferritin and low glycosylated ferritin may also be a marker of excessive macrophage activation. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(5):1027-1028.

- Webb BJ, Peltan ID, Jensen P, Hoda D, Hunter B, Silver A, Starr N, et al. Clinical criteria for COVID-19-associated hyperinflammatory syndrome: a cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2(12):e754-e763.

doi - Moore JB, June CH. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19. Science. 2020;368(6490):473-474.

doi pubmed - Special Expert Group for Control of the Epidemic of Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia of the Chinese Preventive Medicine Association. [An update on the epidemiological characteristics of novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19)]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41(2):139-144.

- Channappanavar R, Fehr AR, Zheng J, Wohlford-Lenane C, Abrahante JE, Mack M, Sompallae R, et al. IFN-I response timing relative to virus replication determines MERS coronavirus infection outcomes. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(9):3625-3639.

doi pubmed - Lau SKP, Lau CCY, Chan KH, Li CPY, Chen H, Jin DY, Chan JFW, et al. Delayed induction of proinflammatory cytokines and suppression of innate antiviral response by the novel Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: implications for pathogenesis and treatment. J Gen Virol. 2013;94(Pt 12):2679-2690.

doi pubmed - Loscocco GG, Malandrino D, Barchiesi S, Berni A, Poggesi L, Guglielmelli P, Vannucchi AM. The HScore for secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, calculated without a marrow biopsy, is consistently low in patients with COVID-19. Int J Lab Hematol. 2020;42(6):e270-e273.

doi pubmed - Behrens EM, Koretzky GA. Review: cytokine storm syndrome: looking toward the precision medicine era. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(6):1135-1143.

doi pubmed - Brisse E, Matthys P, Wouters CH. Understanding the spectrum of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: update on diagnostic challenges and therapeutic options. Br J Haematol. 2016;174(2):175-187.

doi pubmed - Filipovich AH. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and related disorders. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009;2009(1):127-131.

doi pubmed - Yam LY, Lau AC, Lai FY, Shung E, Chan J, Wong V, Hong Kong Hospital Authority SCG. Corticosteroid treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. J Infect. 2007;54(1):28-39.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.